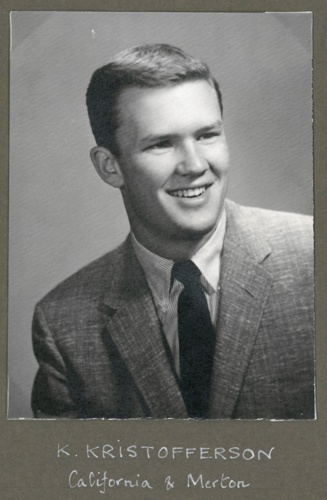

“The first thing to remark about Kristoffer Kristofferson,” writes the Warden of Rhodes House in January 1961, “is that he is a very nice man.” Letters in the Rhodes House archives suggest that few in Oxford or Pomona would disagree. “We admire him and we like him.”

Kris came to Oxford in 1958 with ambitions of becoming a writer, accompanied by an acknowledgement that he was still very much looking for exactly how to apply his undoubted talent. “I want to be a writer, and I am, therefore, anxious to continue the study of literature,” he remarks in his 1957 Rhodes Scholarship application. But, “I do not consider myself very scholarly, and I do not think I would like a life of undiluted study.”

One of the references included with his application starts, “There is more energy and talent wrapped up in Kristoffer Kristofferson than I have seen in any one person in a long time. This is a rough diamond, but the toughness is all there.” It goes on, “He cannot quite be pinned down or pin himself down too concretely, and yet he has an intense drive to do some one thing. One has the feeling that, if he ever makes up his mind on anything important, he will be an organised force to reckon with.”

As a self-confessed unscholarly Scholar, there was clearly something that set Kris apart. Lawrence Hartmann (New York & Merton 1958) recalls, “Kris and I studied Old and Middle English together at Merton College, with some humor and some skepticism. That Kris became one of the most famous Rhodes Scholars of our generation, without becoming a politician or an academic, is probably a tribute to his talents, his poetic adventurousness, openness, and charm.”

The beginnings of Kris’s musical career are also apparent from the archives, reported with what one might imagine as the stereotypical bemusement of Oxford professors encountering something rather alien to them; one notes, ”he has run a radio programme of his own of which he composed certainly the words and I think I am right in saying the music”; another reports him, “singing folk-type songs of his own making and accompaniment on the radio”. Oxford has a somewhat unique vocabulary, but appeared to struggle to describe country music in the late 1950s. Even if the Oxford establishment didn’t quite understand it, some of the students clearly did: “despite his fan-mail he remains modest and rather serious.”

His reports stress that the radio show, his representation of the University in boxing and Merton College in rugby was never to the detriment of his work. By the time Kris left Oxford at the end of 1960, his passion for literature remained undimmed. He was granted a third year of a Rhodes Scholarship and had planned to write a thesis examining the influence of James Joyce’s “Ulysses” upon “The Sound and The Fury” and “As I Lay Dying” by William Faulkner. But a two-year military obligation was weighing heavily on his mind and after the first term of his third year, Kris left Oxford, bound for Germany as a helicopter pilot (laying the ground for possibly the most famous story, the oft-embellished tale of a stolen helicopter and Johnny Cash’s lawn).

The literary ambition of his 1957 application and his time in Oxford remained with Kris throughout his career in which he continued to see himself primarily as a writer. In a much-quoted 2012 interview he said, with characteristic modesty, “I never think of myself as any kind of artist, I just do the best I can. The only reason I’m recording at all now is because I’m a writer. I’m not a great singer.”

Rhodes Scholars pursuing careers in the creative arts were unusual in the 1950s, and continued to be so for many years after. Kris provided an inspiration to other Scholars who found themselves in an Oxford environment that seemed to undervalue the arts. Topé Folarin (Texas & Harris Manchester 2004) was one of these. “I deeply admired Kris Kristofferson—a true polymath who embodied the Rhodes ideal in so many ways. I listened to his music and watched his movies while I was at Oxford, and when I took my tentative first steps as a writer I was inspired by his example. He was the best kind of artist; sensitive, vulnerable, perceptive and immensely skilled. I will miss his presence."

These days, we do believe that Oxford and the Rhodes Trust are much better at understanding the importance of the creative arts. We have been very pleased to stay in touch with Kris throughout his career, and we were delighted to welcome him back to Oxford for our 110th anniversary celebrations in September 2013. During the event, Kris performed three of his most famous songs at a reception in the Ashmolean Museum; we are proud to present a recording of this below. We will miss him greatly.