Síofra Pierse is the Head of the School of Languages Cultures and Linguistics at UCD Dublin, where she lectures in French and Francophone Studies. During her DPhil studies at Trinity College Oxford, she specialised in 18th-century French historiography and history of ideas. Her latest book is Voltaire: A Reference Guide to his Life and Works (Rowman & Littlefield, Lanham MD).

Those who knew me back in Oxford will be familiar with the name “Voltaire”, mainly because my DPhil was on Voltaire’s historiography and I was rather voluble back then about the French philosopher’s significant impact on modernity. As a postgraduate, the Rhodes-Voltaire-Oxford combination was the perfect trio for me, given that the world centre of Voltaire Studies is at the Voltaire Foundation, Oxford. Voltaire was such a pivotal figure in 18th-century Europe that he continues to pop up everywhere. Like Voltaire, I spent three truly seminal years of my life in England, but I admit that the identification stops there!

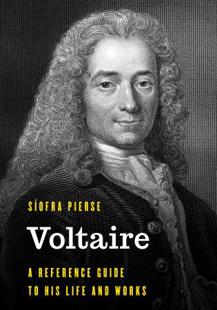

Before Covid struck, I was invited by US publishers Rowman and Littlefield to write a reference guide to the life and works of French 18th-century philosopher Voltaire (1694-1778), which would be part of a series on “Significant Figures in World History”. Undoubtedly, Voltaire was a particularly significant figure in his day and has remained a critical voice ever since. Most notably, throughout his long and prolific life he was an inconvenience and a thorn in the side of authority, whether church, judiciary, or crown.

One of the things that stands out about Voltaire is the uniqueness of his life performance. Even his name is a total construct. He was born François-Marie Arouet, but quickly adopted the penname Voltaire. He liked to style himself as an aristocrat named M. de Voltaire. When he died in 1778, he was whisked out of Paris propped up in a carriage wearing a powdered wig so that his nephew could bury him in church grounds, since most church figures abhorred him. His first grave in Sellières was marked XX, with the intertwined initials A and V capturing Arouet crossed with Voltaire. His brain went to the Comédie-Française theatre and his heart was secreted within a seated statue of the philosopher by French sculptor Houdon. Later, in 1791, Voltaire’s remains were twice exhumed and he was finally interred by the Revolutionaries with massive state funeral pomp and ceremony at the Panthéon in Paris, where his grave may be visited today.