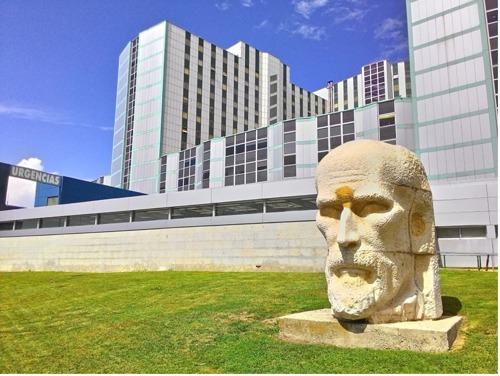

When I was teenager, standing on the steps of Madrid's Ramón y Cajal Hospital, I looked up at a quote inscribed in gold leaf above the entrance. The words came from Santiago Ramón y Cajal, Spain's first Nobel Prize winner in medicine: "Todo hombre puede ser, si se lo propone, escultor de su propio cerebro" — Every man can be the sculptor of his own mind, if he sets himself the task.

At that moment, surrounded by the grim reality of friends dying from AIDS, those luminous letters offered something I desperately needed: hope that I could shape my own future through learning.

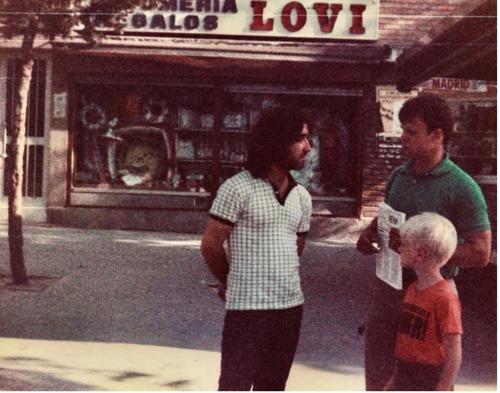

I grew up in San Blas, a working-class neighborhood in Madrid that was home to Europe's largest drug supermarket in the 1980s. My parents were Christian missionaries who founded a drug rehabilitation center called Betel. Our family apartment became "Hotel Tepper," a constant stream of recovering heroin addicts who became my brothers and sisters. They shared needles, and almost all the early generation died of AIDS.

While other missionary kids might have aspired to follow their parents' calling, I found my sanctuary in books. Our home was sparse, almost monastic, but books filled every corner. My father had built floor-to-ceiling bookcases, and volumes were stacked like stalagmites on the carpet. My parents believed books had the power to transport and transform you.

Every morning and evening, we gathered for what my father called "pontifications" — light readings from the Bible, St Augustine's Confessions, Dante's Divine Comedy, and countless others. As a restless child, I sometimes hid A Child's History of the World under my Bible, coloring the faces of Xerxes and Abraham Lincoln while the readings droned on.

In the late 1980s, as the dollar lost half its value against the peseta and tithes dwindled, even the inexpensive missionary school became unaffordable. My mother home schooled us and taught us how to learn. She fanned the fire of curiosity and set us free to roam the world of books. Without textbooks or formal instruction, my brothers and I taught ourselves compulsively as we read encyclopedias, almanacs, and countless books.

When my nine-year-old brother Timothy died in a car accident in 1991, followed by the deaths of Raúl, Jambri, and countless friends from the neighborhood over the coming years, books became more than education — they became survival. My older brother David sent me all his college textbooks, and I devoured them.

My friend Jambri, a former bank robber turned Betel leader, sent me books from Naples and a small Italian Bible that became my constant companion. Through his letters and recommendations, I devoured Dante, Boccaccio, and Ariosto in the original. What began as language study became a lifeline when he and so many others succumbed to AIDS. We read to know we’re not alone. Books were solace and comfort.

In college I read obsessively and piled high the books in my room at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. I stacked them high as if building a wall in my room, unsure of what I was even keeping in or out at that stage.

I was trying to live for two, pursuing the dreams Timothy and I had shared. Yet I was living only half a life.

When I applied for the Rhodes, I struggled with what to write. The first rule of writing is to write about what you know, and all I could write about was San Blas and the work of my family.

At the final interview, when Professor Benjamin Dunlap asked me to translate some lines from Dante in Italian, I finally understood what those years of reading had given me. Not just information, but the ability to connect across centuries with writers who also knew exile and loss. Reading gives us the power of words to make sense of chaos.

When I got the Rhodes, I remembered the quote from Ramón y Cajal and thought, “We are the sculptors of our own minds; we are the authors of our own lives, and we become the stories we tell ourselves.” That’s what I had told myself for years and came to believe.

(Credit: Richiguada, Creative Commons)

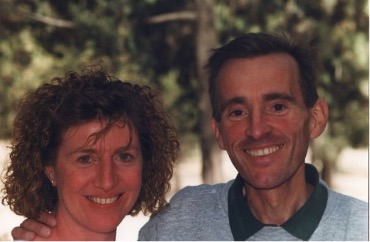

How wrong I was! We do not do it alone or bootstrap ourselves. My parents read to me at the dinner table every night, and David selflessly gave me all his college books. My friends gave me love and encouragement. My professors at Chapel Hill adopted me, and even friendly strangers like Professor Dunlap saw a spark in me and gave me a chance. I couldn’t have done it without them. No. We don’t do it alone. It is our family and friends who give us the tools to become ourselves. Our friends show up when we need them. And even when they are gone, we hear their familiar voices speaking, encouraging, and guiding us.

When my friends were dying of AIDS around me in high school, I often wondered what the answer to suffering was. The answer to suffering, as my mother always said, is more love. As Dante wrote, it is love that moves the sun and the other stars. It is love that makes us who we are: love of family, love of friends, and even the love of learning.

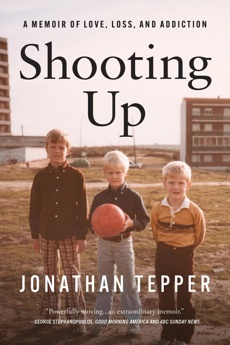

Shooting Up: A Memoir of Love, Loss and Addiction is published by Little Brown in the UK and Infinite Books in the US.