Tuesday, 13 May 2025, was a day of unique symbolism and significance at Rhodes House. Its flagship film fora, showcasing impactful films and bringing together a global community to spark ideas for meaningful change in response to global challenges, would finally take place. This particular forum hosted screenings of two documentary films, Daughters of Chibok (2019), an 11-minute virtual reality (VR) film, and Mothers of Chibok (2024), its full-length 2D feature sequel. The two films were created by Nigerian visual and social impact storyteller, Joel ‘Kachi Benson, to commemorate the abduction of 276 schoolgirls by Boko Haram from their hostels in the community of Chibok (Nigeria) on 14 April 2014. These films tell not just a tale of tragedy, but also of remarkable triumph. They celebrate the power of the human spirit, and of community, in overcoming adversity.

The Sequel, Mothers of Chibok, was particularly impactful. While Daughters of Chibok tells of the horrible events of the tragedy from the girls’ perspective, its sequel provides “real time” insight into the homes and lives the girls were brutally snatched from, and the mothers left behind to pick up the pieces. The audience was taken into a deep-dive of the mothers’ day-to-day lives, beyond that fateful day. The film portrayed how these women, though pain-stricken with grief over the fate of their daughters, were able to continue living, and that with unfathomable resolve. They had not forgotten their beloved girls, no. Rather, the very memory of them and the faith that they would be returned, gave them strength and fortitude. The mothers of Chibok washed their girls’ laundry, frequently looking at their photographs and reminiscing about fond times past.

For the audience, it was an odyssey into irrepressible and defiant hope. The tragedy did not, and could not, break the mothers’ spirits… it did not define them. What came to define them, if anything, was their forming of a circle of support for each other. They found the power to “move on” in community; unity became their superpower. These women became one another’s therapist. As the screening went on, there was laughter and giggling, there were tears and sighs, and finally… awe and amazement, among the audience. The film was truly stand-out! Its potency lay not in sensationalising or commodifying the pain of the (now) young women and their mothers, but in celebrating their resilience and perseverance. It is a celebration of femininity and womanhood at their most indomitable. Mothers of Chibok is a visual ode to the necessity and power of matriarchy in the success of every human life… of entire communities. The screening was a deeply emotive and moving experience.

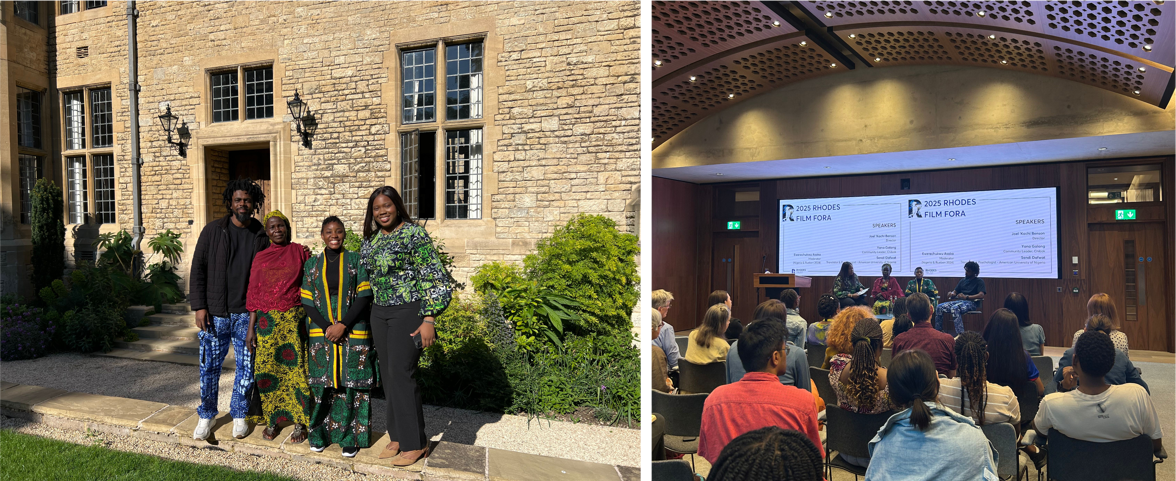

Immediately after the screening, were post-film discussions with a panel comprised of: Joel ‘Kachi Benson (Filmmaker), Yana Galang (Community Leader in Chibok), Sendi Dafwat (Translator and Trauma Psychologist), and Eberechukwu Asaka (Moderator). The discussions provided further, more substantive insight into life on the ground in Chibok, 11 years after the abductions. Some of the challenges and complexities of creating the film were also a topic of discussion. Filming in the impacted community entailed a process of earning their trust. ‘Kachi Benson told of how he and his film crew had to live with and among the community, be a part of their way of life, in order to build rapport. More in focus was the trauma and ongoing process of healing and recovery for the girls who returned (some 160 as of 2019). The audience was also given the opportunity to ask pertinent questions that gave further credence to just how necessary these films are to not only institutional memory, but also possibly retrieving the missing young women and ensuring they have a life to return to. The latter is a life where they will be supported, understood and their recovery prioritised. In all, the discussions were a revelatory exploration of the real impact of the 2014 tragedy, honouring the trauma and healing of families, especially the returned young women, and for some, also the children born to their captors in captivity.

That these two films were hosted at Rhodes House and Oxford University is symbolic and significant for a number of reasons. Mainly, the girls of Chibok were abducted not for any crime of theirs, but for their pursuit of a better life through education, spurred on by their mothers. The executors of their abductions were driven by nothing but religious fundamentalism and bigotry. They were fueled by a deeply entrenched belief that a woman’s place is exclusively in servitude to a man within the confines of a household. On the other hand, Oxford University and Rhodes House host communities of “free” individuals and thinkers whose explicit aim is to innovate, change the status quo, and “stand up for the world,” using education as a medium. What seems like two extremes, antithetical realities as it were, collided on the 13 of May. The chief aim being to lend weight to the immutable truth that education is a powerful weapon with which to dismantle chains of myriad kinds, particularly poverty and inequality.

More than anything, however, this film forum validated that the greater tragedy to that of 2014 would be, as Joel ‘Kachi Benson so aptly asserted, “to choose to look away and move on.” Ultimately, what happened in Chibok should propel us all to choose what it is we will be remembered for. It is a question of legacy, really. That legacy ought to be fuelled by, among others, keeping the daughters and mothers of Chibok in memory, as we seek to- in our individual and collaborative pursuits- “stand up for the world!”