Bruce Boucher is an art historian who served as Director of Sir John Soane’s Museum from 2016 to 2023. Specialising in Italian Renaissance, Baroque, and Neo-classical art and architecture, he is the author and editor of several books, including Andrea Palladio: The Architect in his Time (1994); Italian Baroque Sculpture (1998); and Earth and Fire: Italian Terracotta Sculpture from Donatello to Canova (2001).

After a career divided between academia and museums, I was appointed Director of Sir John Soane’s Museum in 2016. Situated in the London Borough of Camden, the Soane is the smallest of Britain’s national museums, but it is also a “total work of art”, created by one of the most complex and controversial figures in British architecture. I first visited the museum during my time at Oxford in the early 1970s but only began to look at it seriously when I began teaching at a course on the history of museums at University College London towards the end of that decade. At that time, the Soane Museum was a place to be alone with one’s thoughts, and it is still sometimes mischaracterised as “a hidden gem” even though visitor numbers, post-Covid, reached 135,000 last year. The collection is famous for William Hogarth’s “A Rake Progress” and what is arguably the best painting by Canaletto in the country as well as over 40,000 other precious books, drawings, and objects distributed across three starred, Grade-One listed Georgian buildings in Lincoln’s Inn Fields. A quirky place, the Soane garners accolades such as being one of “thirteen alternative cultural wonders of the world that you have to see in your lifetime” as reported in the British magazine Time Out. The British Government also decreed in 2007 that the buildings and collection of the Soane Museum were of national and international importance, and it is under the tutelage of the Department for Culture, Media, and Sport.

Sir John Soane’s Museum has cast a spell over generations of visitors, evoking delight but provoking, at times, bafflement if not confusion. Its creator intended it to be a repository of all that was best for the formation of a modern architect; more generally the house and its collections were conceived as an academy for the enlightenment of the general public as well as a catalyst for the creation of new art by future generations. The density of the display and the juxtapositions of Greek, Roman, medieval, and even non-western objects can seem puzzling. To be sure, elements of this display can find points of comparison in other collections of the period; yet there is much about the Soane Museum that is sui generis. This can be explained in part because it is a rare survivor of a kind of private house museum that was common in the London of Soane’s day; at the same time, the perennial fascination of the Soane reflects its place on the cusp of the shift from the Renaissance cabinet of curiosities towards the post-Enlightenment museum.

The Museum is much more than the sum of its parts and is one of the most intensely autobiographical statements conceived in three-dimensional terms. It has been said that every portrait is a portrait of the artist, and this observation could be applied to the display of Soane’s house and museum. Yet, there is a paradox in Soane’s self-portrait, for while the architect appears both directly and indirectly throughout, he remains an elusive presence rather like the reflections in the convex mirrors that adorn so many corners of the building. In the opening of his privately printed guide to his collection, Soane famously said that the works in his collection were arranged “as studies for my own mind”; yet he never explained what he meant by that phrase. While it is clear that Soane wanted to direct the visitor’s attention to individual objects as well as clusters, he withheld the key, being content to scatter breadcrumbs for later generations to follow. It was also characteristic of the way in which John Soane engaged with the world at large by an admixture of generosity and combativeness. Because the display in the Soane Museum is so personal, it is necessary to consider briefly the man behind the extraordinary achievement that is Sir John Soane’s Museum before turning to the collection itself.

John Soane born at Goring-on-Thames in Oxfordshire in 1753. Although his family had connections with the building trade, they were modest at best. Both his father, who died when John was fourteen, and his brother William were bricklayers, and John’s working life began in a similar manner. Like Michelangelo, who also “curated” his own biography, John Soane would later elide his early years and merely refer to “a natural inclination to study architecture” as the vehicle for his advancement. Soane distinguished himself at the Schools of the recently created Royal Academy where his success was crowned with a gold medal awarded by the Academy’s first President Sir Joshua Reynolds as well as a traveling stipend for study in Italy. Between 1778-80, Soane participated in the Grand Tour, attaching himself to wealthier travellers and making contacts that accelerated his career upon his return to London. But Soane did not rise through talent alone: his wife was an heiress, whose wealth enabled him to build his dream house in Lincoln’s Inn Fields and to amass important artefacts that he left to the nation at his death in 1837. Still, fate did not smile upon Soane: the early death of his wife led to an estrangement from his two surviving sons, and many of his most important buildings—the Bank of England, the Law Courts at Westminster, and the Masonic Lodge in Great Queen Street—were subsequently consumed by demolition or fire. Then, too, his idiosyncratic approach to architecture won him enemies, both real and imagined, and his surviving son George contemptuously described his father’s house and museum as a mausoleum to his own glory.

Soane compared the façade of No. 13 to “the prologue to a play”, preparing the visitor, to some extent, for what lay inside. Drawing upon classical, medieval, and even modernist elements, Soane created something unexpected here, something “less fettered by classical precedent” as one contemporary put it. Completed in 1813, the façade is built of Portland stone and projects a little over one metre in advance of the line of terrace houses on the north side of the Fields. Surprisingly, there are no classical orders here but rather incised, vertical lines suggesting pilasters. Four gothic pedestals from Westminster Hall flank the central windows, which were initially open and only glazed in 1829 and 1834; above are two copies of Greek caryatids in the then new, synthetic material known as Coade stone. The overall proportions were spoilt by the addition of a full upper storey in 1825, bringing the façade in line with its neighbours, Numbers 12 and 14. Soane clearly intended the façade to be provocative, and in this he was all too successful. The European Magazine of 1812 recorded a variety of reactions to Soane’s façade. Some found it pleasing while others condemned the façade as a “new-fangled projection” and a “palpable eyesore”.

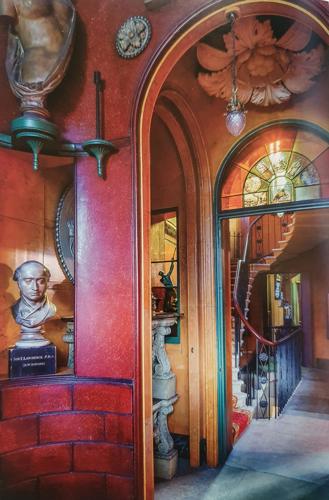

The house itself is mildly unconventional through its flow of space and wall colours inspired by the Pompeiian decoration Soane admired as a young man. It also makes prolific use of mirrors, both convex and conventional, to multiply the illusion of space while coloured and stained glass create an atmosphere that early visitors likened to Mediterranean sunlight. Initially, Soane’s architectural practice operated behind the house proper in what would originally have been a yard or stables, and it was this area, running behind three contiguous houses that formed the genesis of Soane’s museum or “academy” (he used the terms interchangeably). They are essentially a series of interconnected galleries, lit by skylights and attached to the house so that the plan of the house and museum is in the shape of the letter “T”.

The focal point of this suite of galleries is the Dome area, so called because its skylight has the form of a dome. To enter this area is like stepping into the mind of a Neo-classical architect. Under the dome, visitors are surrounded by marbles and plaster casts of classical and later architectural elements, as well as burial urns, busts, and an Egyptian sarcophagus in the crypt or Sepulchral Chamber below. This is the heart of the museum, and at one end presides the bust of John Soane, looking across the sarcophagus below to a plaster copy of the Apollo Belvedere for illumination, or, to put it differently, the scene resembles an Enlightenment quest for immortality. Soane’s bust is flanked by diminutive figures of Raphael and Michelangelo created by his friend and fellow Royal Academician John Flaxman. The message conveyed by this placement appears to be that Soane felt himself to be in direct descent from these great figures, and he would have endorsed their belief that one could not be a great architect if one was not also a great artist. Given Soane’s pessimistic cast of mind, the tableau may also indicate that he believed he represented the end of a great tradition, one stretching back through the Renaissance to antiquity.

Having served as director of the Soane for seven and a half years, I have been able to observe visitors’ reaction to and sometimes bafflement by the collection. Occasionally, they even get lost. In his will, Sir John specified that everything should be left as nearly as possible as in his day; hence, labels within the museum are minimal. While this is part of the Soane’s charm, many visitors want to learn more about what it all meant to its creator. My book, John Soane’s Cabinet of Curiosities, attempts to decipher some of the mysteries around the biggest curiosity of the museum: namely, John Soane himself.

John Soane died on 20 January 1837. Four years earlier, he had lobbied Parliament for an act to preserve his house and collection for public use. This was a novel and, indeed, controversial gesture on Soane’s part, one which engendered a certain amount of debate at the time concerning the nature of museums and just who was the museum-going public. In the end, Soane prevailed, and the Act of Parliament of 1833 vested Nos. 12 and 13 Lincoln’s Inn Fields in Trustees, who were instructed to give free access to the public: “at least on two days in every week throughout the months of April, May and June, and at such other times as the said Trustees shall direct, to Amateurs and Students in Painting, Sculpture and Architecture…for consulting and inspecting and benefitting by the said collection. The Trustees and their successors shall not (except in the case of absolute necessity) suffer the arrangement in which the said Museum…shall be left…to be altered.” In other words, Soane wanted no material changes to the house and collection as he left it. The bulk of his fortune, some £30,000 would be set aside as an endowment, and interest from its investment, together with the rental income from No. 12, would provide an income to support the running of the Museum. Unwittingly, however,Soane was here setting up problems that successive curators and trustees grappled with over the next century and a half.

In his privately printed Description of the House and Museum of 1835, Soane states that had he been able to build his house and museum as a unity rather than piecemeal, it would have looked different. He goes on to quote an early French mentor on the plan of a building as manifesting the genius of its creator. One can say that Soane’s evolving ideas for his house and museum demonstrate an ability to extract the maximum effect within a relatively small compass. In his printed guide, Soane provides plans, sections, and elevations to aid the visitor to thread his or her way through the maze. In the early 1800s, Soane seems to have toyed with the idea of imposing a chronological and typological sequence on his collections, but practical factors militated against it. What we have today is much more creative.

A salient aspect of Soane’s displays is the avoidance of chronology or segregation of objects according to conventional typology such as Greek, Roman, or post-classical. Soane’s written comments refer primarily to the “striking effects of light and shade” as well as the sources of the works purchased or donated to the collection. The whole ensemble could be described as variations upon a theme; yet the overriding logic seems one of a visual association and even opportunism rather than a purely antiquarian impulse. Soane orchestrates the visitor’s experience through the manipulation of light and shade as well as a journey from larger to smaller spaces. The strategic deployment of mirrors amplifies the sense of space and provides what Soane and his contemporaries would have described as “picturesque” vistas.

In the nineteenth century, opinion was divided about this experience. Professionally trained museum curators were put off by the seeming illogicality of what they encountered. One German visitor compared the experience of visiting the Soane to “a feverish dream” while another compared it to “the large stock of an old-clothes-dealer…squeezed into a doll’s house”. On the other hand, some early visitors were more appreciative, and the fledgling Museum was praised in 1836 by a Franco-German architect Jacques Ignace Hittorff for its ingenious sequence of spaces and magical treatment of light, coloured glass, and mirrors as well as its enormous quantity of riches. Furthermore, Hittorff stated that “the Soane Museum not only contains all that could serve for the education of an architect, but everything that could render it attractive…Such an ensemble would be very precious, but it has an inestimable value in England where the elements necessary for the instruction of architecture are comparatively lacking in the only public institution, the Royal Academy”. This was an important point because painting took pride of place in the Royal Academy since it offered more lucrative careers for budding artists than did sculpture or architecture. Soane was aware of this defect in the Academy, and he went on toplay a prominent part in the establishment of what would eventually become the Royal Institute of British Architects in 1834. His collection of casts, models, drawings, and books remained a major resource for the study of architecture until the end of the nineteenth century.

Soane spent much and liberally to acquire choice objects for his collection. The most expensive was the great limestone sarcophagus of the Pharaoh Seti I (reigned 1294-1279 BC), for which he paid £2000—as much as he paid for the freehold of his first house in Lincoln’s Inn Fields. It had been excavated in the Valley of the Kings by the Italian adventurer Giovanni Battista Belzoni in 1817 and was brought to London for exhibition before being placed on loan in the British Museum in 1821. It was subsequently turned down by the trustees of the British Museum, but Soane “saved it for the nation” amid concerns that the Czar of Russia would snap it up. Soane had to knock a hole in the rear of No. 13 in order to bring it into the basement, and its arrival was celebrated by three days of festivities in 1825. This represented the apex of his celebrity as a collector, and Soane invited the cream of society to “view the sarcophagus by lamplight”, employing a manufacturer of stained glass and dealer in lighting to provide lamps throughout the house and inside the sarcophagus at a cost of £80, which was some four times the annual wage of a labourer.

At that date, hieroglyphics remained an impenetrable language, and few, if any, in London would have had an inkling of the significance of the sarcophagus. Soane’s printed remarks stress its workmanship, the fact that it was hewn from one block of stone, and was “…illustrative of the customs, arts, religion, and government of a very ancient and learned people…” Soane grouped a few Egyptian pieces around the sarcophagus, including the eighteen fragments of its lid, which as contemporary illustrations indicate, he placed, rather poetically, underneath it. Initially, a foliate Egyptian capital of black marble was also placed nearby, which Soane acquired from the estate of the Scottish architect Robert Adam, together with numerous marble and plaster reliefs of classical and Renaissance works. The Egyptian capital was subsequently moved to another spot, where it now sits beneath a cast of a Roman capital with floral decoration as if to suggest a communality of vegetal motifs across the ancient world. A similar association can be found in the extraordinary “Architectural pasticcio” that Soane composed for the small courtyard of his house. Some thirty feet high, it comprises architectural fragments including a cylindrical antique altar surmounted by a capital that Soane believed to be “Hindoo”; it is, in fact, a Moroccan capital of the sixteenth century. Above that is a Roman capital, a copy based upon those of the Temple of Vesta at Tivoli. Soane subscribed to then fashionable arguments about the syncretic nature of architecture of the Indo-European world, and much of Soane’s display of architectural fragments appear to follow such visual links.

Looking back from the twenty-first century, one can detect a synchronicity between the renewed popularity of Sir John Soane’s Museum and the rehabilitation of Soane’s reputation as an architect. The latter took a more than century to achieve, for throughout the nineteenth and earlier twentieth centuries, Soane’s work was damned with faint praise or simply damned as wilfully eccentric. In the twentieth century, Soane was gradually hailed by Modernists and Post-Modernists as a prophet of their movements, and this in turn kindled renewed interest in the strategy behind Soane’s display. Most people today would agree that it is fortunate that the museum was not reorganised along conventional lines or according to chronological genres in the last century as almost happened in the 1930s. I think we can recognise now that the nineteenth-century concept of the museum as a systematic and impersonally organised presentation of objects is only one way of looking at history. Our renewed interest in earlier museums and in cabinets of curiosity reflects a desire to pursue diverse epistemological paths and to reconsider the museum, per se, as an archaeological site worthy of exploration. In this way, one can say that the twenty-first century has caught up with Sir John Soane.

Sections of this essay are adapted from John Soane’s Cabinet of Curiosities: Reflections on an Architect and his Collection by Bruce Boucher, published by Yale University Press on 11 June 2024 (ISBN: 9780300275698).