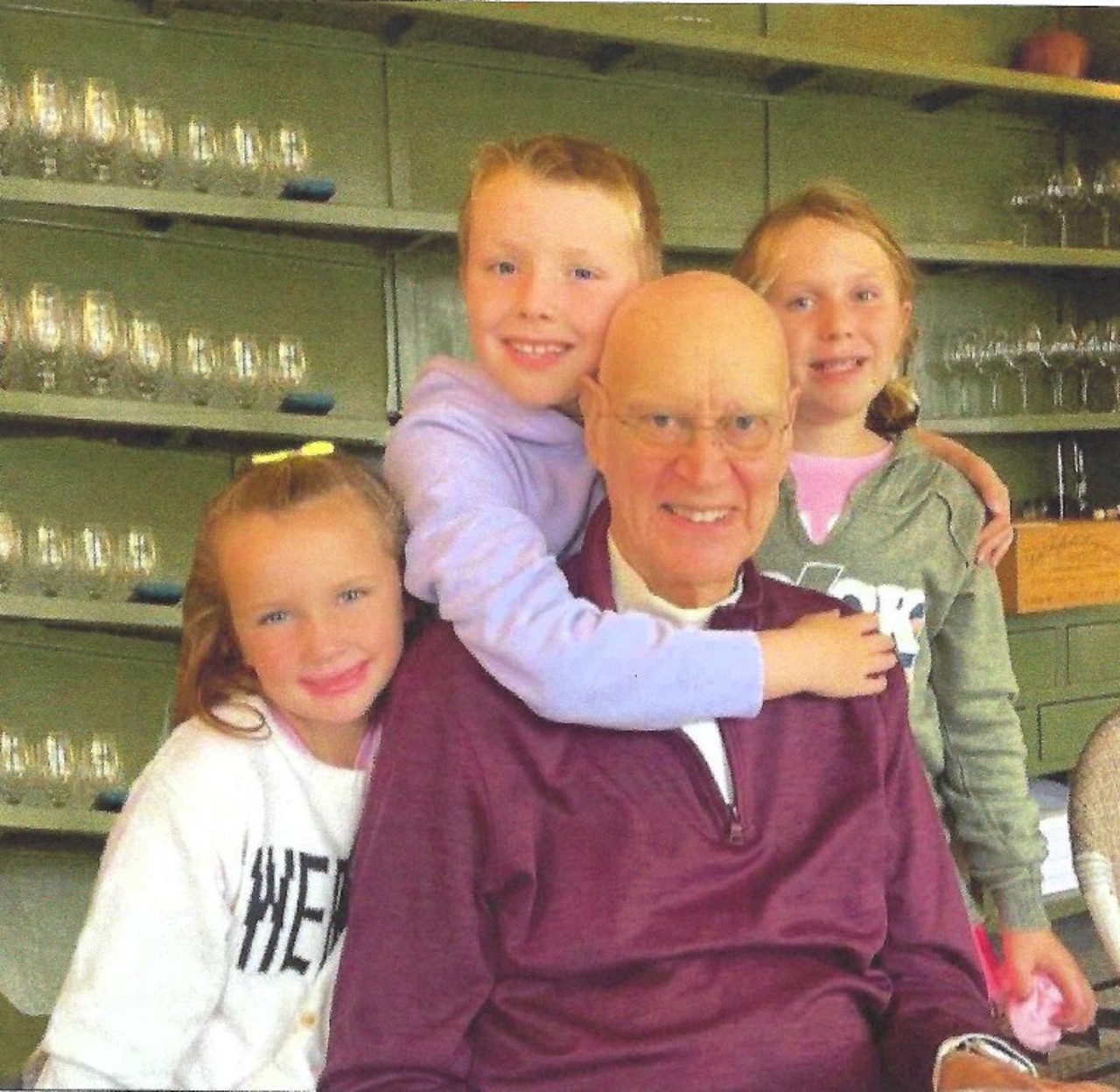

Born in East London, South Africa in 1937, Willie Pietersen studied Law and Economics at Rhodes University before going to Oxford to read for a second undergraduate degree in jurisprudence. Returning to South Africa, he began to practise law but chose to leave South Africa because of its apartheid regime. Pietersen then began an international business career, first in leadership roles with Unilever and then serving as CEO for a range of other multibillion-dollar businesses. In 1998, he became Professor of the Practice of Management at Columbia University. His published works include Strategic Learning and Leadership: The Inside Story. This narrative is excerpted from an interview with the Rhodes Trust on 1 May 2025.

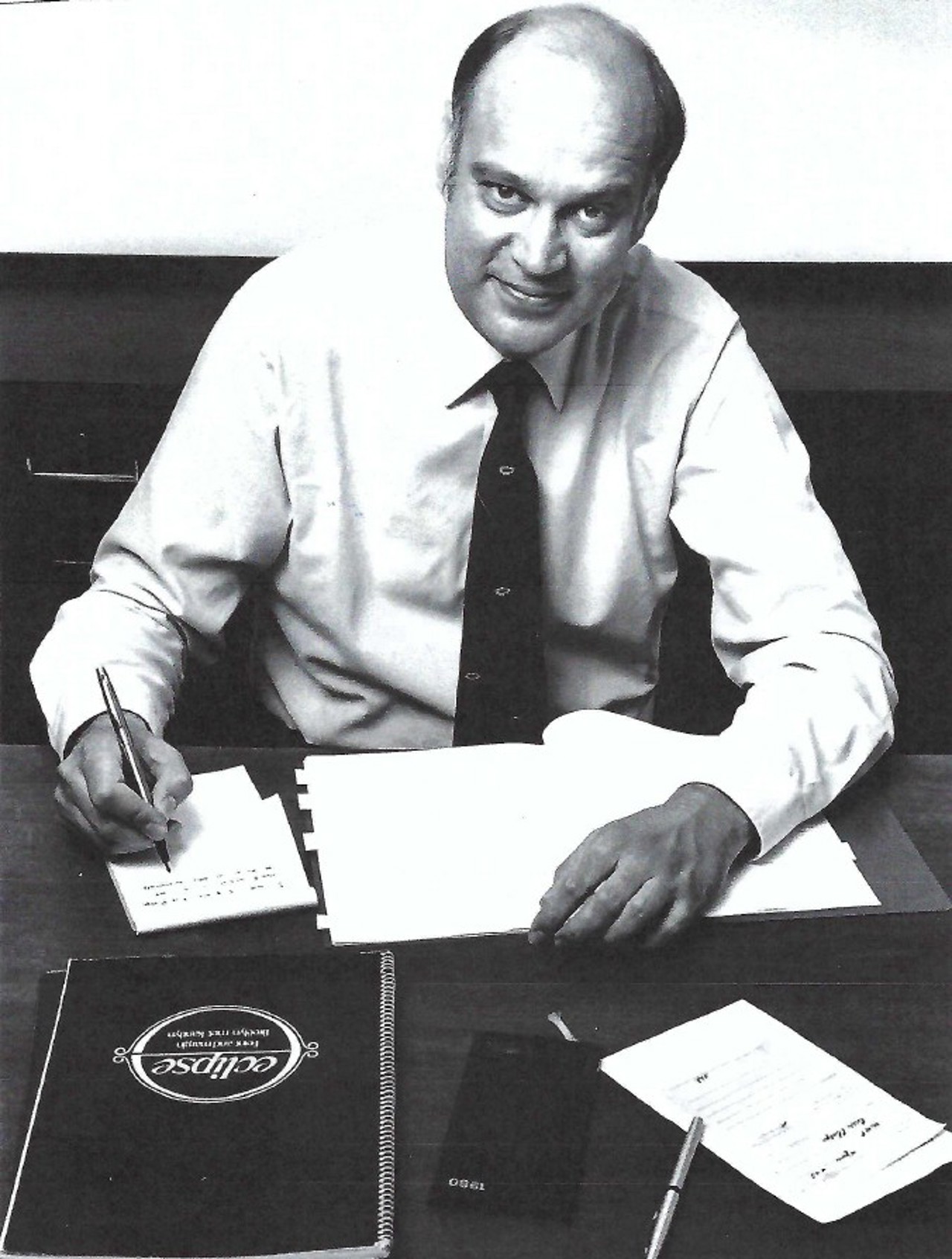

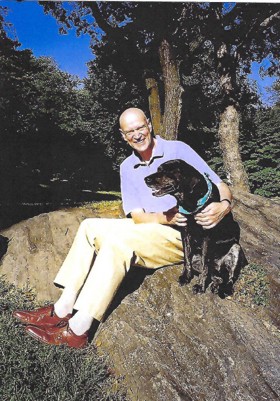

Willie Pietersen

Eastern Province & University 1961

‘This was the world I grew up in and I knew no other’

My mother was of German origin and my father of Dutch origin. They were people of very modest means and neither of them was formally educated. My mother was a homemaker and a person of boundless curiosity. She stressed the importance of education over and over again, and one day she said, ‘I want to tell you about two wonderful universities that exist in the UK. One is called Oxford and the other one is called Cambridge. They’re full of tradition and learning, and one day maybe you’ll get the opportunity to go to one of those.’ My father was a station master on the railways, and he demonstrated what I saw as moral courage: he signed up as a volunteer to join the Allies in World War Two, saying, ‘I’ve thought about it and it’s the right thing to do.’

We moved around a lot because of my father’s work. I went to six different schools before I was 12, and they a few were one-room schoolrooms where I would see the older children learning and be impatient to catch up. From the age of 13 I went on to an all-boys’ school called Selborne College, which was then all white. At that time, the custom – not yet heavily enshrined in law – was nevertheless that of racial segregation in this country that was 90% non-white. This was the world I grew up in and I knew no other. The Dutch Reformed Church which we attended literally defined the separation of the races as the will of God, and after a couple of these fiery sermons I told my parents I no longer wanted to go there. From there a journey of transition began in my thinking.

When I was 11 years old, a new government came into power. They introduced inhumane legislation requiring that people live in separate residential areas and stipulating that they could not go to the same schools or hospitals. Sexual relationships across the colour bar were illegal and punishable. My parents became very disturbed by this, but the discussions I had with them were about the harshness of it, not about the justification for having a separate life. I only learned to question that subsequently, and the strongest part of that was going to Oxford and seeing South Africa from the outside in.

On applying for the Rhodes Scholarship

I had an older sister, Phoebe, who was very clever and out there in front. When the opportunity arose for me to go to university in South Africa, my parents could only afford to send one of us. Phoebe insisted it should be me. It was an act of tremendous generosity and sacrifice which I’ve never forgotten. As a child I had overheard my parents saying to one another, ‘Oh, he’s a real little lawyer, this one,’ so it became natural for me to want to study law. I went to Rhodes University where I got involved in student government and became chairman of the Students’ Representative Council. That was my first experience of leadership, and I began to see that it was about being a steward for the interests of others, that leadership is not about power, it’s about service. I also participated in protests against the apartheid system, campaigning for academic freedom and equality in the pursuit of education regardless of colour.

I had done a BA and an LLB, so I was ready to go out and practise as a lawyer. Then one day, just before graduation, I happened to be staring at a noticeboard when my economics professor tapped me on the shoulder and pointed at a notice encouraging applications for the Rhodes Scholarship. He said, ‘You should apply for that. You’re an ideal candidate.’ I had academic and leadership strengths but had done only moderately well at sport, and I gathered from one of the committee members that my selection was a close call. After Oxford I became a committee member in Rhodes Scholarship elections in Cape Town, and I realised how hard it was to make choices between candidates based on the criteria. It’s an important responsibility, because you realise how much it’s going to change people’s lives.

‘The tutorial system took me by surprise’

Oxford was a major personal growth experience for me. Britain at that time was still recovering from the austerity of the war. Rationing was relatively recent, but there was this sense of rebuilding too. I loved watching That Was the Week That Was with its playful British sense of humour. I also got the chance to travel through Europe. My friends and I couldn’t afford to hire a car, but a British student sold us a 1934 Austin for 30 pounds and it took us everywhere.

The tutorial system took me by surprise. Initially I was overawed by it: the fact that I alone was under scrutiny, but I had a wonderful tutor called Tony Guest. He had the sharpest of minds but he was also very kind, like a shepherd of learning, and we became the greatest of friends. He suggested that I should become an academic. At the time, I said ‘No,’ because I wanted to go back to South Africa and practise law, but when I took up my position at Columbia many years later, my boss at the time wrote me a note that could have come from Tony. It said, ‘I knew they’d get you in the end.’

“Why don’t you teach?”

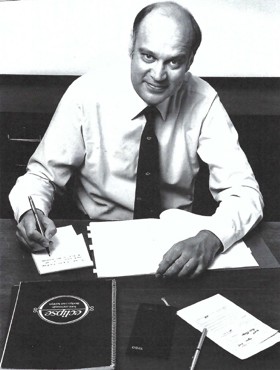

I enjoyed being a litigation lawyer. You must be quick on your feet in real time, and you’ve got moments in time which are decisive. I began to develop an interest in corporate work, and I remember when one major client asked me for business advice and then offered me a managerial role in their firm. I said ‘No’, but it triggered something.

The next major trigger was representing families in front of something called the Race Classification Board which adjudicated issues of defining people’s race to determine where they could live, which school they could go to, who they could marry. It was vile to observe these indignities: putting a pencil through somebody’s hair to test its crinkliness; examining their skin pigment as if they were laboratory specimens. I was able to ask a contact to call in a favour with the Minister of the Interior to ensure favourable outcomes so the people concerned could continue undisturbed with their lives. But I released there were probably thousands of others who had rulings against them with no fair right of appeal. I said to my wife at the time, ‘We cannot continue to live here.’ She agreed, but I wasn’t qualified to practise law anywhere else, and so, I joined Unilever and in due course I got postings to Australia, to Holland, to the UK and then to the US. Ultimately, we decided to stay in the US. I remember being in our home in Connecticut and seeing Nelson Mandela released from prison when he gave his majestic speech about creating a rainbow nation. As an act of leadership, I don’t know of any other example of this kind of transformation against the odds at this scale. It was a very moving experience.

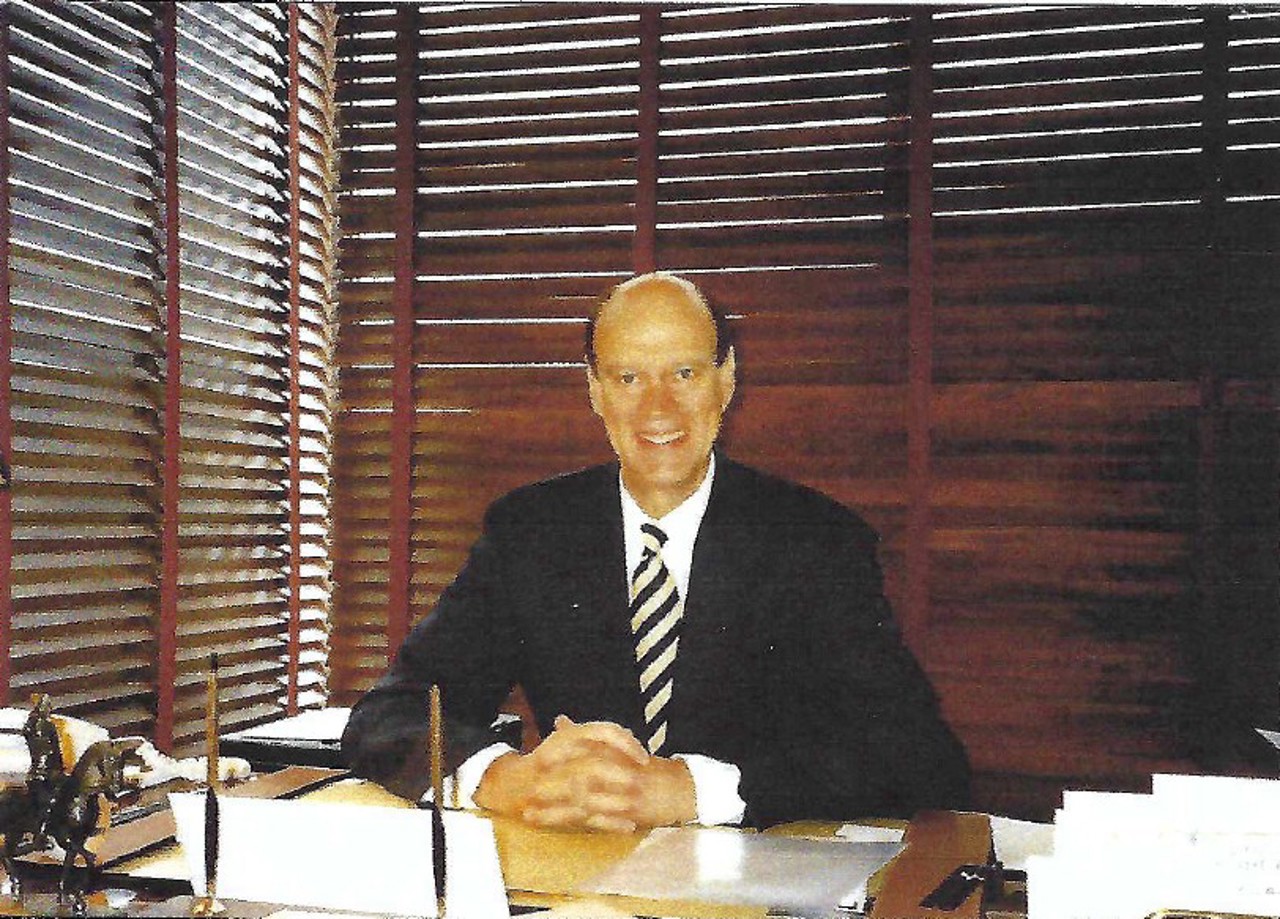

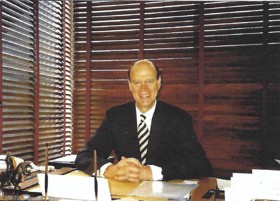

In the US, I had been brought in to transform the loss-making foods subsidiary of Unilever. It was demanding, not just in terms of the business turnaround but to get the people in the team to believe in themselves. We did it together, and I remember that experience very fondly. I subsequently got CEO roles in bigger organisations and I was having very fulfilling career. Then, when I was in my late 50s and thinking of taking on another business role, somebody I knew well said, ‘Why would you want to do that? In every conversation we’ve had, you’ve talked about the joy of learning, and you’ve talked about leaders as teachers. Why don’t you teach?’ I did some sessions on business case studies for Columbia and then they asked me to come onboard as a professor of the practice of management. I’ve been lucky in that I’ve been able to continue in this role for almost 30 years, and I can think of nothing more gratifying.

‘I have always kept a learning journal’

I’ve carved out a niche for myself at the business school as a strategy expert, but I’ve realised over the years that successful strategy rests on the quality of the leadership. It’s about helping people decide the right thing to do, helping them to be critical thinkers. A lot of my thinking comes from what I learned studying philosophy, not just from business books.

One thing I have always done is kept a learning journal. It grew from writing down the meanings of words while I was still at school to things I’d learned in nature study and astronomy and history. It’s a great thing to do as part of being a life-long learner, and I would certainly advise today’s Rhodes Scholars to embrace the habit of keeping a learning journal.

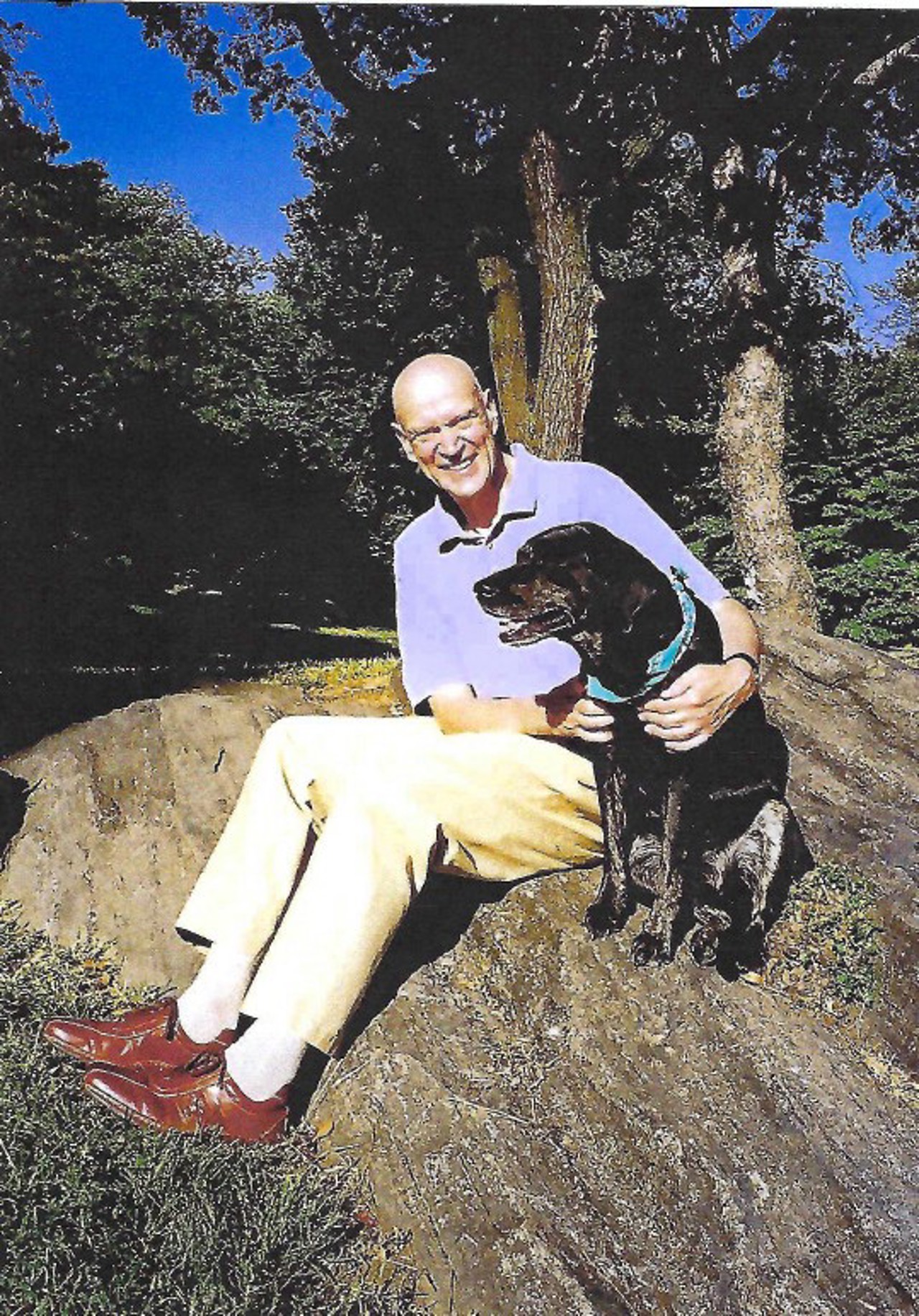

Now, at a somewhat advanced age, I strive to live by this motto: Never retire; keep learning; and live life at a reasonable pace.