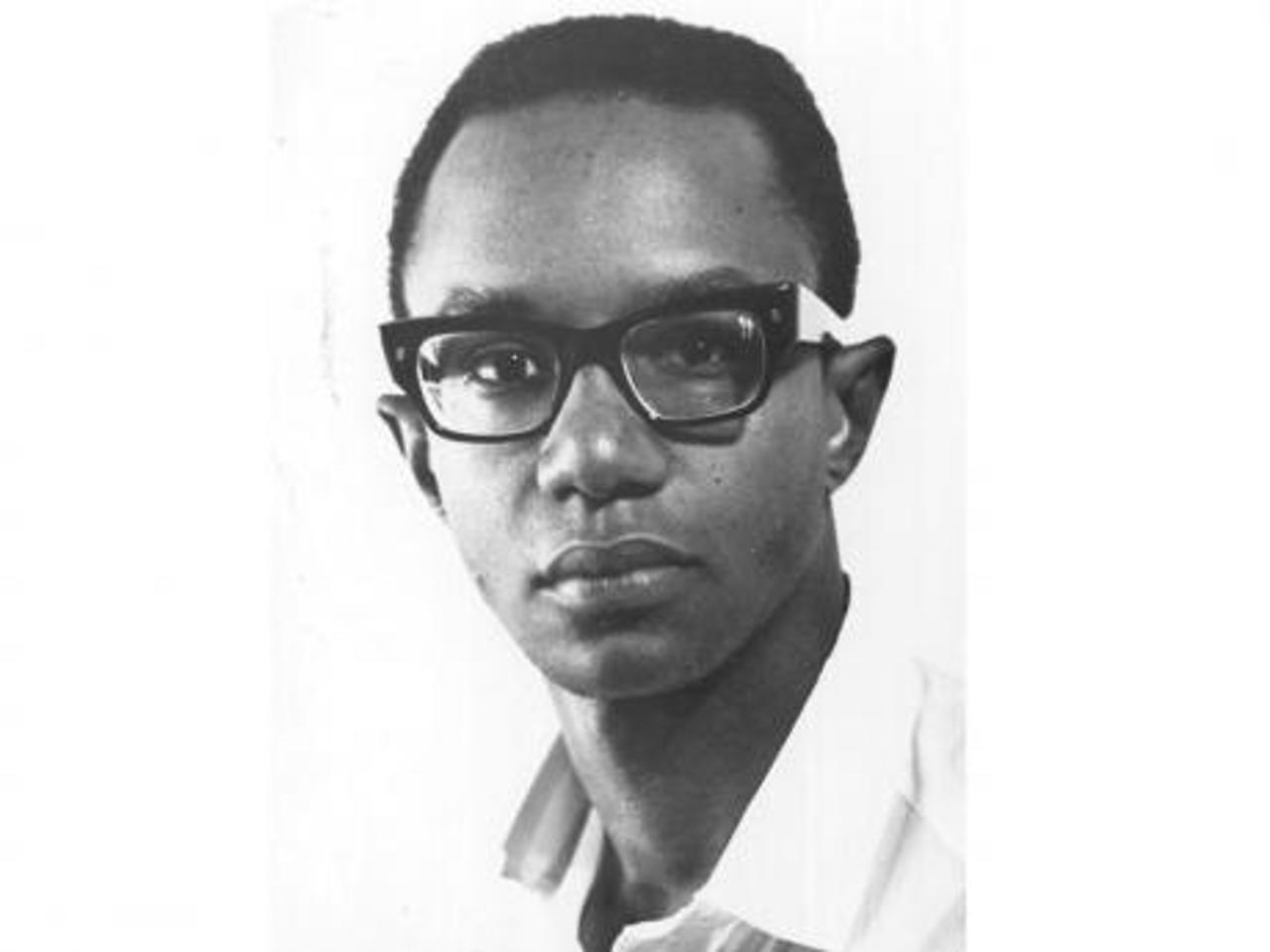

Born in in Jamaica in 1944, Trevor Munroe studied at the University of The West Indies (UWI) before going to Oxford to read for a DPhil in political science. He returned to UWI where, alongside his career in teaching and research, he has worked as a public scholar and civil society advocate, He was a leader of the Jamaican and Caribbean left in the 1970’s and 80’s. Munroe was a co-founder of the Citizens Action for Free and Fair Elections in Jamaica and of the University and Allied Workers Union. He is a member of the international council of Transparency International and has worked on a consultancy basis with organisations including the World Bank and the Carter Center. This narrative is excerpted from an interview with the Rhodes Trust on 12 December 2024.

Trevor Munroe

Jamaica & New College 1966

‘We could feel that the promise of independence was not delivering equality and justice’

I was born at a very interesting time, close to the end of the Second World War and 20 years short of the end of 300-plus years of British colonial rule of Jamaica. It marked the upsurge of the anticolonial movement globally as well as reaching a milestone in Jamaica, because we achieved adult suffrage the same month I was born. We were the first black country to get adult suffrage, 20 years ahead of black suffrage in the United States and so many other mature democracies. My family was very strong and supportive. My father was a colonial civil servant and my mother was a homemaker. They were both full believers in education as the way forward, and that’s what they inculcated in myself and my brother. And, together with my extended family, they were very much part of that rising black middle class that would take over from the colonial rule in the late 1950s and early 1960s.

As children, we were avid sports lovers. I got interested and involved in track athletics, especially hurdling and sprinting. We used to set up motorcar tyres in the road outside our house as our hurdles, to the distress of anybody else who wanted to use the road at the time. My schooling at both primary and secondary level was deeply influenced by Christian religion, and that had a profound influence on me in terms of values and behaviour. You looked out for others and even if somebody had done something bad, you would forgive and reconcile. And the instilling of the urge to learn was very strong. Even in fifth and sixth form I was learning Kant and that sort of thing. Alongside my studies and sport I was also involved in drama and debating. Jamaica was preparing for independence, but we could feel that the promise of that was not delivering equality and justice for the majority of the disadvantaged Jamaican people. And at school, I could see that some of the teachers would give preferential treatment to those who were lighter-skinned or from an upper-class background. That began to turn me to a radical route.

On applying for the Rhodes Scholarship

I entered the University of the West Indies in 1962, the year of Jamaica’s independence and the year after the Cuban Revolution when Fidel Castro took over. Those events, along with the developments in the Civil Rights movement in the US framed my undergraduate career. I always handed my essays in on time and made sure they were of high quality but at the same time I was extremely involved in student activism, both in student governance and leading demonstrations. I have a particularly strong memory of being part of the inter-hall champion debating duo with Walter Rodney, who went on to write How Europe Underdeveloped Africa and who was actually assassinated in 1980 because of his activism. At university, I took part in the All-American Debate Championships, representing the UWI, and I remember that unforgettable experience of coming face to face with rest room signs in the South US marked ‘Blacks’ and ‘Whites.’

For the Jamaican lower middle class and upper middle class during the colonial period, the Rhodes Scholarship was always a pinnacle of academic and scholarly achievement. So, when I got First Class Honours at UWI, applying seemed like the natural next step. My Rhodes interview was held at Kings House, and coincidentally the day before, I had led a student demonstration against the moves in Southern Rhodesia to establish an apartheid regime. One of the members of the committee said, ‘Why are you here?’ and I said, ‘Look, to be honest with you, it’s about time some of Rhodes’s money, exploited from black people, returns to black people.’ I guess the frankness of my response impressed, and the rest is history.

‘Challenging but incredibly fulfilling’

During my undergraduate studies, I had been drawn increasingly to political science, and my DPhil at Oxford was about the extent to which former colonies were attaining independence but with the same legal and unequal social structure as before, what the French Martinican philosopher Frantz Fanon called “false decolonisation”. My time at Oxford was challenging but incredibly fulfilling. At New College and then especially at Nuffield, I formed friendships with people from across Europe and the US, and from the British left in particular, but most of all from Africa and Asia. We took a very strong stand in Oxford against racial discrimination in the town of Oxford, and against authoritarianism in the university system. Then there was the Vietnam War, and finally the anti-apartheid movement.

With everything I was doing, I had to be very, very attentive to make sure that my scholarly work was on target. I do recall that things reached a point where one day, towards the end of my second year, the Warden of Rhodes House called me in and said, very politely, ‘Trevor, I’m not saying that you shouldn’t be doing what you’re doing, but I need to remind you that the third year of the Rhodes Scholarship is optional.’ It was a word to the wise, and I did get my doctoral work done in less than three years, but it didn’t stop me doing what I had to do, including demonstrating in against the in London against the Vietnam war and outside the Jamaican High Commission when Walter Rodney was banned from returning to Jamaica.

‘We faced tremendous resistance’

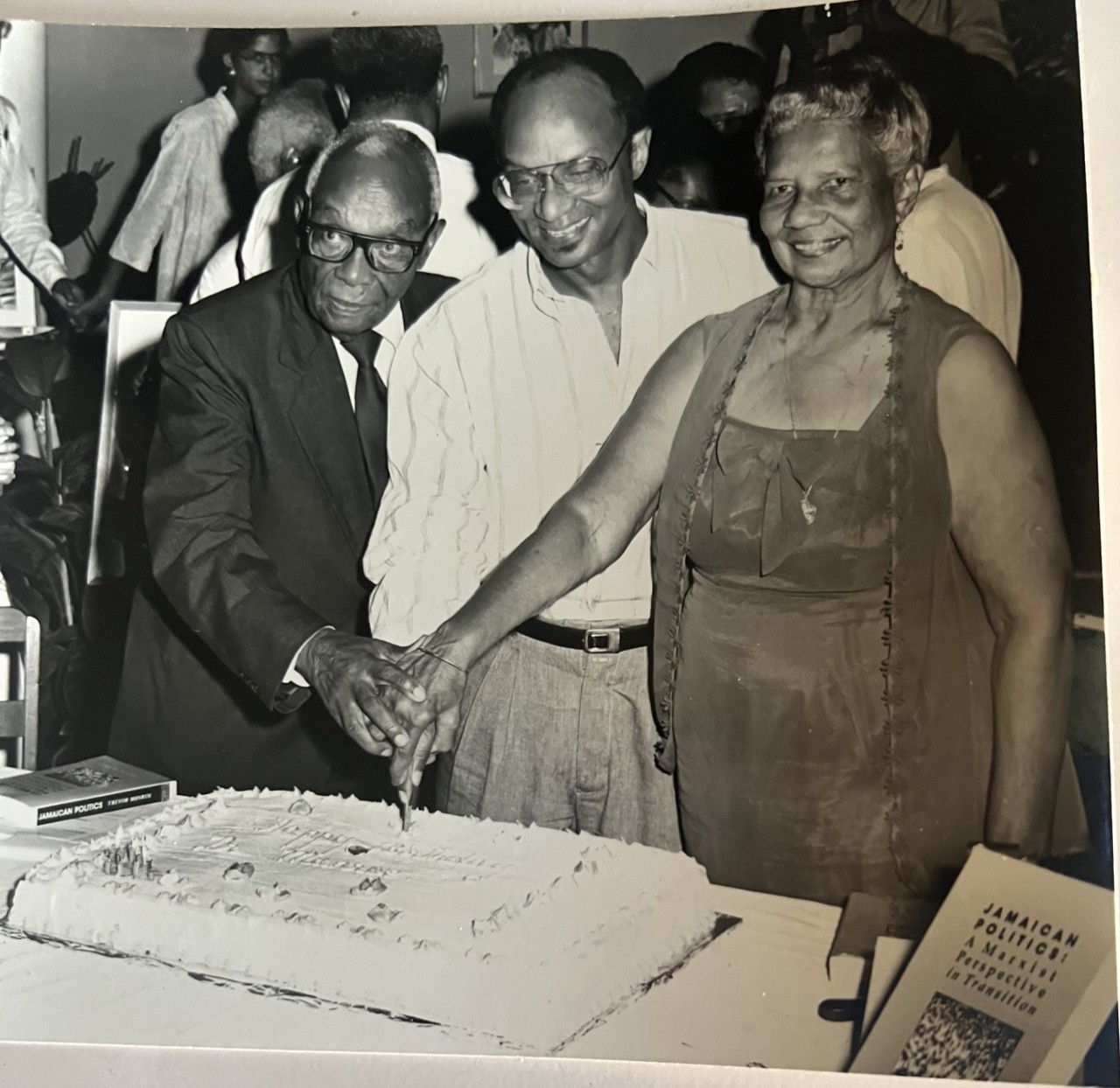

My life since Oxford has been that of a public scholar. I was an academic first of all and I was at the University of the West Indies for 40 years, teaching, writing and doing research. My special area was democracy and democratisation, particularly in the Caribbean, and it has been especially fulfilling to encounter leaders here in the Caribbean who say, ‘Look, I was in your class at such-and-such a time.’ That makes me think, ‘Well, it wasn’t all in vain.’

Alongside that was my work as a civil society activist. I helped to found the election watchdog group in Jamaica, the Citizens Action for Free and Fair Elections. And when I returned from Oxford in 1969, some of the janitors and groundspersons working in UWI came to me and said they were not satisfied with their level of union representation, so I worked with them to form a new trade union. That was a baptism of fire, because we faced tremendous resistance from the established trade unions. In 1974, the baptism of fire turned into a baptism of blood. We were packing up to leave after a lunchtime gathering and 20 or 30 thugs came out of nowhere and began really beating me and mauling me with machetes and knives. I had to get 100 stitches. It was an attempt to say, ‘Look, Trevor Munroe, you’re a Rhodes Scholar and you should just leave the working-class business to us and get back to the classroom.’ It didn’t work because the union we formed is now one of Jamaica’s national unions, from that seed planted at the university campus.

I also did work for the Jamaican chapter of Transparency International, the global civil society body and I spent a lot of time hosting and appearing on national media programmes, working in that civil society mode to bring research and enlightenment to issues that needed that. I served in the Jamaican Senate for ten years, as what they call an independent senator, and I pioneered the campaign finance legislation to begin regulating the role of big money that political campaigns. Although there are many professional achievements that I’m proud of, I have to say that the most rewarding experience has been a personal one, being at my wife’s side as she has recovered from a kidney transplant. What keeps me going in all areas of my life is knowing that there has been some progress, even though there is still much of the road that remains to be travelled. It’s a marathon, not a sprint.

‘Don’t expect that you won’t get pushback’

The Rhodes Scholarship had a huge impact on my life. It gave me the opportunity to discover and develop my talents – both intellectual and leadership talents – and take them to a new level. The Rhodes Scholarship taught me that when you stand up for what is right, don’t expect that you won’t get pushback. You just have to take it and remain committed to what you feel is appropriate. To today’s Rhodes Scholars I would say, the way forward is to stand up for what is right and also without compromising your principles be open to conversation and dialogue with opponents so that you can reach common positions with others, whether that’s on the urgency of saving the planet or the urgency of social justice.