Born in Kingsport, Tennessee in 1956, Susan Russ Walker studied at Eckerd College before going to Oxford to read for a second BA in English language and literature. She returned to the US and attended Yale Law School, then clerked for Judge Frank M. Johnson on the Eleventh Circuit Court of Appeals. Judge Walker went on to serve as an assistant attorney general for the state of Alabama and then to work in private practice before being appointed as a US Magistrate Judge in 1996, retiring from the bench in 2022. She is a founder of the Sew Their Names Project, an initiative to bring descendant communities together in a spirit of truth and reconciliation to commemorate the erased and forgotten lives of enslaved persons. Alongside her legal and advocacy work, she has been an important supporter of the Rhodes Scholarships, serving for many years as a selection committee member and as the secretary for Alabama. This narrative is excerpted from an interview with the Rhodes Trust on 15 October 2024.

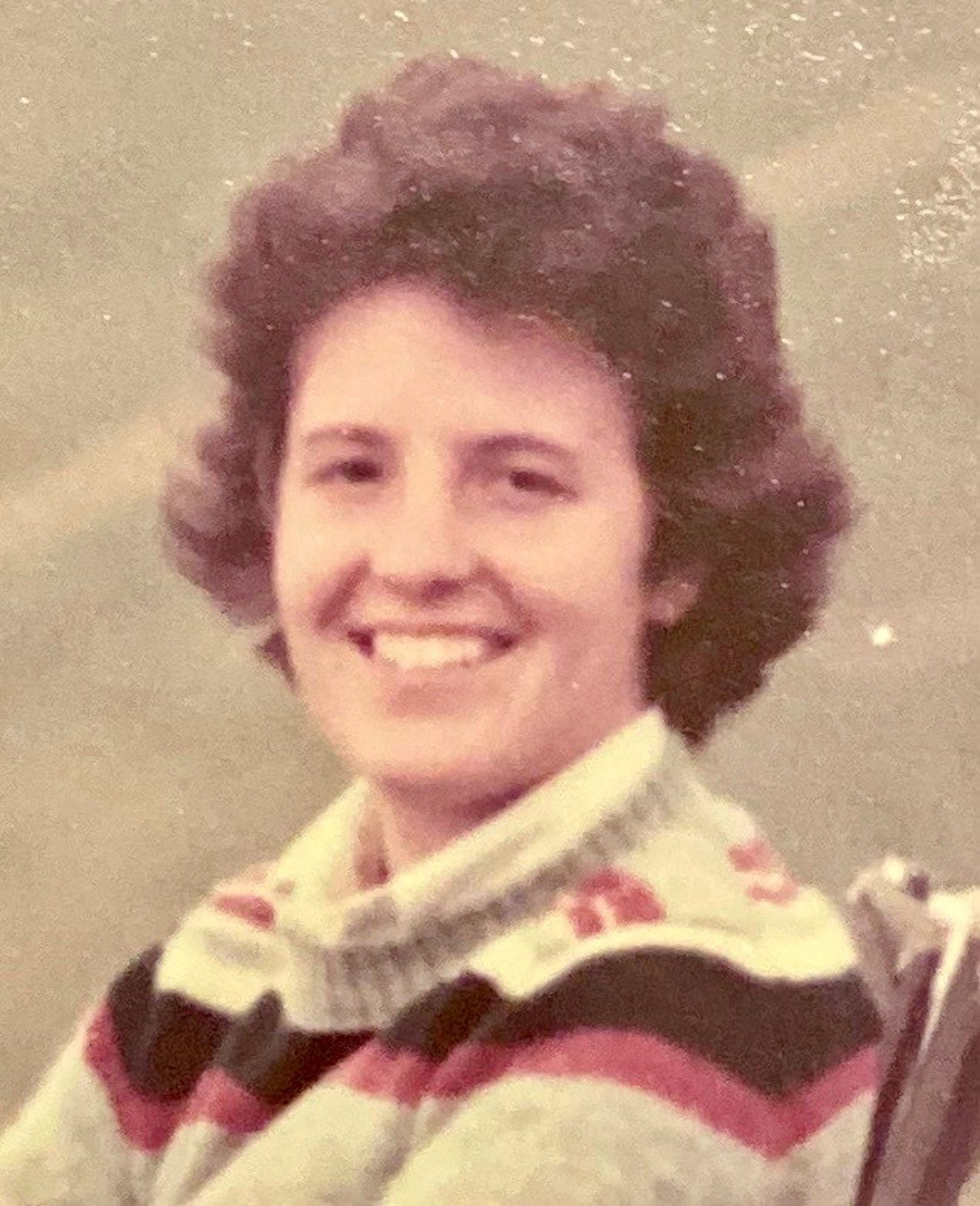

Susan Russ Walker

Tennessee & Somerville 1978

‘It dawned on me that making good grades and working hard meant freedom’

I was born and grew up in a small city called Kingsport in northeast Tennessee. My mother was from Alabama and my father was from New Jersey and New York. He was stationed in Alabama in World War II, and after they married, they ultimately chose to settle in Kingsport. I was the youngest of four, and my brothers and sister were all really smart. I was pretty slow to care about academics myself, but at some point in high school, it dawned on me that making good grades and working hard meant freedom, and freedom, I wanted. So, I started to focus a lot more. Both my parents were a big influence on me, and I think the thing that influenced me most was my mother’s work for access for people with disabilities. She had had polio before I was born, so she used a wheelchair for all the time I knew her. She was very courageous, and I wish she could have been a lawyer. She would have been a good one.

I read a lot, and when I wasn’t indoors reading books from the public library, I was always outside. We were barefoot kids, running around outdoors, and nature and the outdoors became really significant for me. I also played sports: I had brothers, and whatever anybody was playing, we all played. [Judge Walker later earned a half blue in volleyball at Oxford.] Finally, art was always something that mattered to me. In church growing up, I would just sit and draw, and later I had an art teacher who was a big influence. I loved English too. I loved to write, and I was pretty sure that whatever I did would involve writing.

On applying for the Rhodes Scholarship

I went to Eckerd College when I was 16. I chose it because it was where my brothers and sister had gone, too. I don’t think I even applied to another school, and I loved it there. I had imagined I would do political science and then go into journalism, because I had edited my high school newspaper, but I was just immediately won over by studying literature. I also had the chance to study abroad, in London. All of sudden, I was in this amazing world where I could go to the British Museum and look at medieval miniature paintings, or go to concerts or the theatre. And then, of course, we took a bus trip to Oxford. And I thought, ‘This is a beautiful place. I would really like to study here.’

I did not hear of the Rhodes Scholarship until my first year in college, when I went back home and happened to meet William A. Stuart (Virginia & Balliol 1910), who was a Rhodes Scholar. He talked about the wonderful experience he’d had in Oxford, but then I found out that at that time, in 1974, women couldn’t get the Scholarship. I couldn’t believe it. Later in college, I learned that the terms of Rhodes’s will had been broken so that women could apply. I was determined to try, but even so, when I heard that I’d won the Scholarship, I thought, ‘Did I hear that right? How did that happen?’ It’s not like I was convinced that I was just born to be selected. At that point, it was the most remarkable thing that had ever happened to me.

‘It was just a wonderful time’

I sailed over to England with my Rhodes classmates, and that was an amazing opportunity to start to get know them and begin to find my way and feel like this was something I could do. I went to Somerville, and I was well aware that this was a women’s college and did not have the resources of a Balliol or a Christ Church, but I was living in an old Victorian dorm and it all seemed so romantic and different. It was just a wonderful time.

In my course, we started with Middle English and worked through to the beginning of modern English literature, and I really benefited from that. We studied not just Middle English itself, but also the history of the language, and I hadn’t had to do language work in college. I began to uncover some capacity for working harder than I thought, and for persisting at something that was difficult, and that came to matter to me later in my career.

‘Case by case, it was possible to make a difference’

When I went back to the US, I thought that surely every door would automatically open for somebody who had been a Rhodes Scholar. Well, that wasn’t true at all, which was a good lesson. I worked as a writer and was considering a PhD in English, and then I began to think seriously about law. I got more and more convinced that I could do the research and writing I loved in the setting of law, and I saw that I could add into that my interest in public service. So, I applied to Yale Law School. While I was there, I did some work on prison projects, and we also started a group that was interested in public service law. I was lucky to have professors who really shaped where I would go next, particularly Robert Cover, Joe Goldstein and Burke Marshall.

Burke Marshall had been deeply involved, as Assistant Attorney General for the Civil Rights Division of the DOJ, in the civil rights movement. He said he didn’t write recommendations for clerkship positions, but he would make an exception if I wanted to clerk for Judge Johnson. I had already learned at law school that I was really a Southerner, so I was delighted to get the chance to go to Alabama. I don’t think I knew at the time just how much I was learning: Judge Johnson was a remarkable example of someone who had the courage to follow the law and do what he thought was the right thing to do.

When I worked for the state attorney general, I was involved in some major voting rights cases. During that time, I met my husband and we decided to stay in Montgomery. When I became a Magistrate Judge, I learned that, though I may have thought that I would decide cases that would have a big impact on a larger community, so often the most important work I was doing was at the micro level, case by case, person by person. I began to understand, for example, just how serious the consequences of incarceration could be, especially for the families of the individuals who go through it. There are difficult issues around who is detained, who is incarcerated, and those were troubling to me, so I worked very hard trying to find alternatives to detention, including mental health and substance abuse treatment. I tried to persist in the face of calls for the easy decision just to incarcerate. That came to be the most important and the most rewarding aspect of my work, when I could feel that what I did actually made a difference. And I also valued making the effort to think as clearly and dispassionately as I could in every case—to try to make the right decision, explain it well in a tone that was appropriate, and contribute to this culture of argument in a way that was positive.

A few years ago, I began working collaboratively on the Sew Their Names Project. That came about when I found out that my great-great-grandfather, a Baptist preacher, had been a slave owner and had had a role in the southern church’s support for slavery, and that the church he had presided over was still standing. I contacted the pastor of the Black church that now owns that antebellum building, Reverend Dale Braxton, who was incredibly kind and gracious in welcoming me despite what I know now were some doubts. When he said he would like help restoring the building, I started writing grant proposals and researching church history in archives. That’s where I found what were called ‘church books’ which included the names of enslaved persons linked to specific churches. Rev. Braxton’s church had a quilting project, and it occurred to us that one way to commemorate these individuals who had basically been erased from memory would be to sew their names into quilts. We customarily honour people who persisted against the odds and were remarkable in what they were able to achieve, and enslaved people were those people, but they do not appear on monuments in Alabama, although certainly the Confederate dead do. A quilt is a different kind of monument, not stone and brass or a man on a horse, but something made on a human scale.

‘It gave me a willingness to jump in’

It was such an enjoyable experience to be part of the selection process for Rhodes Scholars, and it mattered a lot to me to do what I could to make sure the Scholarship was accessible to as many different people as possible. Going to Oxford as a Rhodes Scholar gave me so much, including the chance to meet wonderful people. It gave me a willingness to jump in and try things, and studying literature meant that I could participate in a bigger world than I had once known existed.

In retirement, I’ve been able to go back to my love of art, and I would say I am now all in, working with wood and using traditional decorative arts as a way to make visible, and pay attention to, what I think of as a vanishing natural world. It’s a bit frightening to start over, but I didn’t want my life to just get smaller as I got older, and I love the challenge of pursuing something new.

Transcript

Interviewee: Susan Russ Walker (Tennessee & Somerville 1978) [hereafter ‘SRW’]

Moderator: Jamie Byron Geller [hereafter ‘JBG’]

Date of interview: 15 October 2024

[file begins 00:04]

JBG: Okay. So, we’ve begun our recording. My name is Jamie Byron Geller and I am here on behalf of the Rhodes Trust with Judge Walker (Tennessee & Somerville 1978). Today’s date is 15 October 2024 and we are here on Zoom to record Judge Walker’s oral history interview, which will help us to launch the first ever comprehensive Rhodes Scholar oral history project. So, thank you so much, Judge Walker, for joining us in this initiative. Would you mind, please, saying your full name for the recording?

SRW: Sure, and I’m delighted to join you. My name is Susan Russ Walker and, you know, I’m sorry, I think I already missed your first question.

JBG: No, no, no. That’s perfect. And I’m just going to share my screen for just a moment. Judge Walker, we’ve been in touch over email around this recording agreement for the Rhodes Scholar oral history project. I just wanted to ask if you’ve had the opportunity to review this and if this all looks agreeable to you and if we have your permission to record audio and video for these purposes?

SRW: Yes, I have reviewed it and you do have my permission.

JBG: Thank you so much. So, Judge Walker, we are having this conversation on Zoom today, but where are you joining from?

SRW: So, I’m in Montgomery, Alabama where I’ve lived for, I’m afraid it’s about 40 years at this point.

JBG: Wonderful. And is Montgomery home for you?

SRW: Not now. We have just, in the last month plus, moved to Chapel Hill, North Carolina, and from there, we’ll be working on building a home in Asheville, North Carolina, in the mountains.

JBG: Wonderful. And so, I’d love to talk about that a little bit further on in our conversation, but first, to go all the way back to the beginning, would you mind sharing where and when you were born?

SRW: Sure. I was born in Kingsport, Tennessee, which is in the upper northeast corner of the state, very close to Virginia. I come from a relatively small town, certainly not a town that numbers in the hundreds, but it was, I think, about 32,000 when I was born there. And the way my family got there, just so I, sort of, explain, briefly: my mother was from Birmingham, Alabama, my father was from New Jersey and New York. He came to Alabama during World War II, was stationed at what used to be called Fort Rucker. They met, and when he returned from the war, my parents sort of compromised on location, somehow. We didn’t have Tennessee roots. I had the, sort of, Alabama background and, of course, the northern background. But they settled on small towns in that part of the world and ended up in Kingsport. So, that’s where I grew up.

JBG: Wonderful. And did you live in Kingsport for your whole childhood?

SRW: Yes.

JBG: Okay. And I would love to know a little bit about your earliest educational experiences there in Kingsport.

SRW: Well, I went to public schools, except for kindergarten. I’m sure kindergarten was at church. I don’t think I was old enough to know, but that must have been how that was done. So, these were just regular schools, in Sullivan County, where Kingsport was, or even Kingsport City schools, now that I think about it, for elementary school, junior high school and high school.

JBG: Great. And were there particular academic subjects that you gravitated towards during those years?

SRW: I think I was slow to care a lot about academics until, probably, my sophomore year in high school. But before that time, and carrying through all the way to the end, I liked English and I liked art. Those were the two things I cared about the most. Toward the end of high school, I had some classes in American government and international relations that I was interested in, and then my mother was insistent that all of us take Latin, so I had a couple of years of Latin as well. But English and art were what I cared about the most. Let me go back a step. I was the youngest of four, and my brothers and sisters were really smart and very accomplished. And I just didn’t seem to care about that much until, at some point in high school, I think, it dawned on me that, you know, making good grades, working hard, meant freedom, and freedom, I wanted. So, I started to focus a lot more then and got more involved in academics.

JBG: And did you have a vision for as you grew up about what direction you perhaps expected your career to take?

SRW: So, no, mostly. There were some influences, I think, on my life that were really important, and that maybe one can see, later one, making a big difference. I read a lot. So did my sister and my siblings, my two brothers. And reading for me meant going to the public library. I don’t remember lots and lots of books in the house. But particularly in summer, we could go every Saturday to the public library. You could check out six books at a time. My sister could check out six more books. We would go through those during the week. We read whatever they had. It didn’t matter, you know, what was available. And so, that was a big thing for me. I was always outside when I wasn’t inside reading. We were, I think, sort of, barefoot kids, running around outdoors. Our property was two-and-a-half acres or so. My father had a very large garden, and behind that was a farm. So, we spent a lot of time in the creek and running around in the fields and climbing up in the barns and those kinds of things. And for me, nature and the outdoors became really significant.

And then, I guess I would say from the very beginning-, well, I’ll just say one other thing. I always played sports, maybe because I had brothers. We were always in some softball game or, later, volleyball game. Whatever anybody was playing, we played, and I didn’t know that girls didn’t, to some extent. I just learned to do that. That was very common for me. And then finally, art was always something that mattered to me, and that could range from being three or four or five. And, you know, the best thing to do in church was to get the little cards that were there for donations, and to get a pencil and draw. So, I would just sit there and draw in church, and then later, you know, do arts and crafts in camp, and then finally, I had an art teacher in junior high who was a big influence, and I learned how to silk screen, which was unusual, and then I took some watercolour classes and an oil class and that, sort of, started to gather a head of steam, I guess, for me.

That didn’t address your question of whether I had a plan, I think. Tell me again what you’re asking there, so I make sure that I do respond.

JBG: Sure. So, just as you were growing up, throughout your childhood, if you had a vision or expectation of the direction that your career might take.

SRW: Yes. So, from a career standpoint, I knew that a couple of those things would be involved, I think. Not only did I love reading, but I loved to write, and I was pretty sure that whatever I did would involve that. And as time passed, I found ways to use those interests or skills. So, I edited the newspaper in this, you know, small town high school newspaper setting. And I mentioned that I had some classes in international relations and American government, and I think I began to think, ‘Well, I’ve got to go to college. Maybe I’ll do journalism and political science, or something like that.’

I started there. I continued to like to write, I edited the newspaper in college, but I really did not like political science. I don’t know if it was the teacher or the subject, but I switched very quickly to English. But there was no grand plan. I didn’t imagine myself as the president of the United States or, you know, in any of those things. I will say this, because you and I have talked before, and I do recall, even though I never thought about being a lawyer, I remember being appointed as a judge at Girls State, which was something I attended as an extracurricular event, and also during a programme that my high school [10:00] sponsored, and maybe that got some traction with me, although I surely did not have any idea what that meant at the time. But those things did occur. I did not know lawyers at all. Nobody in my family was a lawyer. There’s one exception to that, which is my mother, who I think would have been a great lawyer, had a great-great uncle who was on the Alabama Supreme Court, and I must have heard about him at some point, but I certainly didn’t know him and I didn’t know much about him.

JBG: And I think I recall you mentioning, Judge Walker, that you finished high school at 16. Am I recalling that correctly?

SRW: Yes, that’s right.

JBG: And then, did you go right to Eckerd College after high school graduation?

SRW: Yes, I did. My brothers and sister had gone to that college in St. Pete, Florida. My oldest brother went when it was Florida Presbyterian College. He had actually been planning to go to Duke, and I think he had an A.B. Duke scholarship. You know, sort of, great support for going to Duke. But my parents were real involved in the Presbyterian Church and he heard about Florida Presbyterian, this new college that was going to do everything differently and be, you know, innovative and interesting, and so forth, when he was about to graduate, and he decided he was going to go there. I think it mattered to him that he could swim all year round, quite frankly. But once he went there and we were introduced to the college, we just loved it, and all of us ended up going to Eckerd. I don’t even think I applied to another school.

JBG: Wow. And what was your course of study or your major at Eckerd?

SRW: So, it came to be English. That was really as a result of starting, again, thinking I’d do journalism and some sort of political science and then finding out that, number one, there were no classes in journalism – the kind of thing you’d think you’d know before you go, but I really had not known that – and also, again, I think that my political science class was, sort of, a ‘How a bill becomes a law’ class, just like my history class was about, you know, kings and male leaders. And I mean, just, the things that would interest me now were not what they were teaching.

So, I had good English teachers, and I was just immediately won over by studying literature. And I had one professor in particular who knew a lot about early modern Renaissance literature, some medieval literature as well, and also about drama, and I think that’s what really got me hooked. Also, I should have said, I did take art classes the whole time, when I could. It would be, sort of, a one every year, kind of, enterprise. But I studied those and I did what I thought I should do and also took some economics and history and the core classes that were offered which were, sort of, interdisciplinary, so that, you know, I also did philosophy. Just a lot of different things.

JBG: Would you mind sharing a bit about your study abroad experience in London?

SRW: Yes, sure. So, I got to go to London for a semester, and my sister had done it the semester before. I think I was probably 18, 17. I’d have to think about that. I just had never been anywhere like that. You know, my town in Tennessee, which I loved appropriately, didn’t have a museum, an art museum, or anything of that kind. We went to one theatre up in Abingdon, Virginia, which was a good little repertory theatre, but I hadn’t seen much of that. All of a sudden, I was in just this amazing world, and I could go to the British Museum and look at medieval miniature paintings, or lots of other things: I just remember the room that had those. Or I could go to the theatre and it was so inexpensive, we would go to two plays a day sometimes and get 50p tickets for each one and, if the truth be known, sit up in the nosebleed seats and then, when the lights were off, move down to other empty seats.

But it was just eye-opening for me. I’d never been to any classical music concert other than the Kingsport Symphony Orchestra, and they did their best, but it was not the same as the London Symphony. And, you know, just on and on and on: the opportunities were endless. And then, on top of that, you know, we travelled, and that was back in the days when—I mean, I don’t think hitchhiking was a great idea, but I don’t think I was ever dissuaded from it either. So, my friends and I, and then sometimes I by myself, would hitchhike in Europe and up into England and Scotland, and those were just remarkable experiences. So, that was my introduction.

JBG: And you kindly shared, during our last conversation, a conversation that I believe you had right after your freshman year of college that started to introduce the idea of the Rhodes Scholarship, and I was wondering if you would mind sharing about that.

SRW: Yes, I’m happy to. So, I had not heard of the Rhodes Scholarship until my first year in college. And we had something called autumn term at Eckerd, which mean freshman class went early and spent the month of August at the college, and therefore did not need to be there during winter term, which was the month of January. So, I had to find something to do in January, and I went back home, which was, of course, the last thing you want to do when you’re a brand-new college student. But I took a friend with me, and my mother and father had become active in restoring that farm I mentioned behind our house, and it was a lot of acres. So, we were not right on top of it, but we were the next house over, really. And the restoration would have been back to the 1830s, 1840s, I think.

But there was a man named William A. Stuart (Virginia & Balliol 1910) – and they never referred to him as anything but ‘William A. Stuart.’ He wasn’t ‘Bill,’ he always had that middle initial – whose family had owned the farm way back, for years and years. And Mr Stuart lived in Abingdon, Virginia, and my mother wanted me and my friend from Eckerd to go to his house in Abingdon and go through his attic and find things that were related to this farm, which was called Exchange Place. These would have been old, you know, candle moulds and blancmange moulds and dolls and spinning wheels and things from another time entirely. And we did that, but at some point, William A. Stuart asked us if we’d like to have lunch. And he was a very formal, very reserved gentleman, and I’d really never met anybody like him before either.

So, my friend and I sat down with him at lunch. This was lunch with a white tablecloth, linen napkins, and soup. Vegetable soup was the meal. I think there may have been, you know, corn sticks or something with that. But we were in a lovely, very refined dining room. He had someone waiting on him. And he started to talk to us about his life. He was, at that time, quite old, I think. Well, I’ll say this: he is the one who brought up Oxford, and it turned out, he had been a Rhodes Scholar at Oxford, and I think he was elected in 1910. So, his age, then, was quite advanced. And he talked about the wonderful experience he had had, and I remember thinking, ‘Wow, I would really like to do that.’ This was even before I had been to England.

And then, I went back to school and found out that women couldn’t get that scholarship, and I couldn’t believe it. It was an era—it was 1973, when I began school, so, this would have been 1974, early in 1974, and things had been changing for women. I just couldn’t imagine: why couldn’t I apply? So, I think I tucked that away in the back of my mind. And then, when I was on that semester [20:00] abroad in London, you know, we had the canonical bus trip through Oxford, and I remember sitting in the double-decker bus – I was probably high up – looking at the city and thinking, ‘This is a beautiful place. I would really like to study here.’ I mean, it was as simple as that. It wasn’t like I knew anything about it. I just felt, I guess, drawn to it, and also all the more determined when I found out I couldn’t go. And then later, further on in college, I learned that the will had been broken, and women were going to be permitted to apply for the Scholarship.

JBG: I’m curious if you recall learning that you had been selected for the Scholarship and in, as you said, what was then the second class of women Rhodes Scholars.

SRW: I recall being told, yes. Is that what you mean?

JBG: Yes, and what that moment was like.

SRW: Well, I mean, the moment was, sort of, hard to explain and hard to recall, in a way. I just remember thinking, ‘Did I hear that right? How did that happen? Am I actually going to get to do this?’ Because up until then, I thought—as I said, I was determined to try, but I hadn’t been around anybody who’d won it, other than Mr. Stuart, until later, there was a provost for my college who had been a Rhodes Scholar. But for the most part, I just didn’t know anybody who had done it, and even though I wanted to apply for it and try for it, it’s not like I was convinced that I was entitled to do this, that I had been born to be selected to go abroad and have the opportunity. So, I think I was a little bit shocked and dumbfounded, but, of course, I was thrilled. I mean, that was the most remarkable thing that had ever happened to me at that point.

JBG: And did you sail over with your class in 1978?

SRW: Yes.

JBG: Yes. What was that experience like?

SRW: It was pretty fabulous. I wish that everybody could sail now. I’d never been on a ship at all, and certainly not one like the QE2. You know, I feel like I remember almost everything about it. And some of it was just mistakes I made. Like, I didn’t know that if you get to your first table for dinner, that’s where you’re going to be the rest of the time you’re on the boat, that’s your table. So, I didn’t even think about it. The people I was with were great, but I had sort of thought you’d just sit where you’d like, but there was a protocol about that. You had to dress for dinner. I’m not sure I had enough clothes. I’m sure I did my best. I remember strange things, like playing ping-pong on the deck of the ship and watching the ball not be exactly where I thought it would be, because the ship was moving.

But the most amazing thing about the experience was just the opportunity to start to get to know the other Rhodes Scholars and form friendships and acquaintances and talk to people and, sort of, start to maybe find my way, to feel like this was something I could do. And then, it’s just a wonderful interval, almost out of time, to be on a ship like that. It’s not the same as everyday life. It’s a heightened, different, strange and kind of wonderful experience for—I think we might have been on that ship six days, something like that. So, I’ve really never had any experience like that, certainly not before and probably not since.

JBG: And did you live at Somerville when you were in Oxford?

SRW: I did, yes.

JBG: You did. And what was that experience like?

SRW: Somerville, or living at Somerville?

JBG: I would say living at Somerville.

SRW: Okay. So, I was in a Victorian house and, I mean, I thought it was pretty fabulous. I was well aware that this was a women’s college and that it did not have the resources of the Balliols and Christ Churches and Trinities, and so forth. It certainly did not have the wine cellar. But still, you know, my room had leaded glass windows and there was a lot of wood, and the windows were casement windows, and there were no screens – I’d grown up with window screens – and somehow, that was romantic and different. You can just, you know, crank those windows open. Some of my friends had to put, I guess it was 10p pieces, into space heaters, to get heat, but we had what was euphemistically called ‘Background heating,’ and it did its best, and then also space heaters, which were just as good for making toast as for heating, it turned out.

And this was the era of cassette tapes. Those were just coming in. I had friends who had tapes – I’m not sure they were taped legally, but in any event – of albums and music I’d never heard, and I got a tape deck and I’d listen to those and I would just study in that room. And, you know, there were people down the hall, English students, I got to know, and one of the Rhodes Scholars was down the hall from me. It was just a wonderful time. I can’t complain in any fashion. I can remember things that would not, I think, be relevant now, but I’m not sure. If you wanted to call home, you had to go find the payphone and, you know, put in coins, which made my calls home blissfully short. And I had wonderful parents, I should add. It’s just that it wasn’t what I was interested in doing, was calling home. And, you know, I recall pigeon post, which was how we would have to get together. You’d put a message in these little post boxes and they dutifully took those and they were delivered the same day, and then you got a message back, and it might be asking you to go to tea, or asking you to go and do something else. Just a very different kind of system and experience. I also learned to stay off the lawn, which I would not have known, until I committed that infraction a couple of times. I think I was in trouble several times, for various things. It was just a different place, but I loved it.

JBG: And did you read English?

SRW: I did. In fact, I was advised to get a second BA, and that was so, so right. I knew I had some gaps in my education in English, from an undergraduate standpoint, but I don’t think I knew how significant they were, and the second BA let me start—we didn’t have the first year. So, we had two years of the three-year class. So, I missed Old English, and I missed modern English literature. But I had everything else. You know, I think what was regarded as modern in my course might have been Tennyson, but I got to start with Middle English and work my way through, and I really benefited from that, and I think I needed that exposure.

JBG: And I’m curious about activities outside of your academics, or perhaps travel, that might have been part of your Oxford experience.

SRW: So, we travelled every chance we got. I mean, there were those long breaks, and everybody did some studying, and, especially closer to exams, did a lot of studying. But when there was an opportunity, we would take off, and that might be to Ireland, that might be to Europe. One trip was all the way to Greece, and we had actually planned to go on to Israel. It’s possible that I was riding a moped and had a little bit of a wreck and ended up in a Greek hospital for that one. I never made it to Israel, and I think I spoiled some other people’s vacations just a bit. It was quite an experience, and I will never forget flying back to London and being met by Lady Williams. Sir Edgar Williams was the Warden at the time. Lady Williams came to pick me up. I’m not sure she was thrilled with that, but she did bring a pair of Sir Edgar’s socks, which were very helpful for cold feet, because I had a little bit of recuperating to do, and she was very kind about that. But we travelled as much as we could.

JBG: You shared, Judge Walker, that law school hadn’t necessarily something that had been a focus of yours or an aspiration of yours prior to Oxford. I’m curious if that idea started to percolate while you were in Oxford. [30:00]

SRW: Only to the extent that I had a good friend, Virginia Seitz (Delaware & Brasenose 1978), who was thinking about law school. I think her father had been the chief judge of the Third Circuit. I didn’t know what a circuit was at the time, but I think I remember putting in the back of my mind, ‘Oh, so, people actually do that,’ you know, which sounds ridiculous, but I just hadn’t really known anybody who thought about law. So, that occurred.

I think there were some things that were happening at Oxford that also, maybe, made me ready to think about law, even though I hadn’t had much exposure to it. The example that comes to mind is, I did study Middle English and the history of the language, and I remember working really hard at that. I hadn’t really done languages before, and languages, sort of, fell out of the college requirements in the 1970s, so, I hadn’t had to do language work. I’d had a little bit of Latin, again, in high school, but that was all. I remember figuring out that other people actually were going to lectures, not just to see their tutors, and maybe I should do that. And so, I started to go to the lectures for Middle English and for the history of the language, and as I did that, I thought, ‘I really like this.’ I really enjoyed it, and I began, I think, to uncover some, maybe, capacity for working harder than I thought, and for persisting at something that was difficult, or relatively difficult.

And then I remember, also, you know, working very hard to get ready for those exams. I thought that literature came a little more easily, but that work did not, and there was no substitute for just spending the hours, and I started to enjoy that kind of work. And that was one of the great gifts of the experience, was to become, maybe, a bit of a scholar. Maybe that was a fair description, after a point, so that I kind of added in being able to work hard to what I always felt like I had, which was being interested in a lot of different things and open to a lot of different things. So, you know, looking back, I mean, I certainly never used Middle English in law, maybe a little tiny bit of Latin, but maybe some of those habits I acquired from that time fed into that a bit.

JBG: And did you finish your degree in Oxford in early summer 1980?

SRW: Yes, that would be right. I had a viva. I’m sure it was supposed to be ‘Viva voce,’ but they called it a viva exam. So, it was actually into the summer before I finished. But yes, I completed it then.

JBG: And then, did you move back to Tennessee at that time.

SRW: No. Sure, I visited at home, but I was trying to figure out what to do. I knew that I had to make money. I had just run out of funds. I looked for a job in DC, because I had friends who were going to be there, and I thought surely every door would automatically open for somebody who had been a Rhodes Scholar. That was a good lesson. I don’t think I fell on the worst side of being entitled, but I do think when I left Oxford, I believed I would just sashay into Washington and just have any kind of work I wanted to do, on important policy things, or whatever it was. Well, that wasn’t true at all, and I ended up getting a job as a writer, which was really what I was capable of doing at that time, with an English degree.

So, I got a job as a writer for a couple of years. I was at that time thinking about would I, if I could get the means, go back to grad school in English and get a PhD and teach, which was really, at that point, what I had set out to do, or would I start to think of some other career. And as those couple of years – really, a year and a half or so before I applied to law school – as that time evolved, I think I got more and more convinced that I could do some of the things I loved, like researching and writing, in the setting of law, but I could add to it a public service orientation. I don’t believe at all that teaching isn’t public service. It’s maybe one of the purest forms. But I had realised that I had an interest – and this goes back to the journalism and political science studies, I guess – in, sort of, public affairs, public events, and I thought, you know, law might be the right thing for me to try. So, I applied to law school.

JBG: And so, you went to law school at Yale?

SRW: I did.

JBG: Okay. What was that experience like, at Yale Law?

SRW: Very different from anything I had done before. There’s, you know, what I know now I might have expected, but just didn’t know enough to know, that I would, you know, go through, as every student did, the basics, like tort and contracts and constitutional law, and adjust to that kind of legal culture. There certainly were plenty of people at Yale who loved law, were drawn to it, always knew they’d do it. I was not that person. But I came to find things that I really did care about, and some of them were extracurricular. I did a good bit of work on prison projects and visited a couple of prisons that were local, and actually came to be, sort of, in charge of one of those programmes. We created a group that were interested in public interest or public service law, and I spent some time doing that.

But I think I just fell under the influence of two or three professors who shaped, to a large extent, where I would go next, and those were Joe Goldstein, who taught criminal law, Burke Marshall, who taught quite a number of things, but First Amendment law and some civil rights law, and then, finally, Bob Cover, Robert Cover, from whom I took a class in legal history. [break 37:44-37:53] So, Joe Goldstein’s class on criminal law was really different from anything I had imagined, and it was quite wonderful. It was not at all about reading criminal statutes or looking at that, sort of, black-letter law. I remember the exam as being something like, ‘Write your own criminal code and explain what the values are that lie behind it, and why do you think we should do what we do when it comes to deciding what we regard as criminal behaviour?’ and that was something I was really interested in, I learned that I was really interested in, and I worked really hard on that class.

And then Burke Marshall had been an under-secretary, assistant, I guess, attorney general for civil rights under Bobby Kennedy, and he had been deeply involved in the civil rights movement from the standpoint of the Justice Department officials, who were working in particular in Alabama, but elsewhere as well. Burke Marshall was the one who passed me on to Judge Johnson in Alabama, and we can talk about that if you’d like.

JBG: Yes, yes.

SRW: I can return to that. And then, finally, Bob Cover taught me legal history, and I’ve realised later that some of his work had a big influence on me as a judge, and I remember some of his writing on what judges do. So, one of the things he said was, ‘A judge articulates her understanding of a text and, as a result, somebody loses his freedom, his property, his children, even his life.’ And that was, kind of, a perfect [40:00] encapsulating of what my life became. When you talk about articulating your understanding of a text, that’s really what judges do a lot of the time, is just that sort of interpretation that, for me, built on the work I did studying English. But I began to understand what the consequences were of making those inferences from text, reading text, being in a culture of argument and making decisions, and then, the sort of impact that actually would have on other people.

So, what Robert Cover did, I think, in the end mattered the most to me. He also introduced me, and all of us, to legal history, from the standpoint of various events in the country. It wasn’t like he was trying to go from the beginning to the end. It was more topic-based. So, it might be the Salem witch trials, slavery, the railroads: you know, different, sort of, vignettes that one could learn a great deal from. And I think that may have sort of brought me to history, and history is something I learned to read and be interested in after that time, and not just in a legal context. I think I came to be somebody who wants to read about history and lots of different topics, depending on what’s going on around me. So, law school had a big influence, not just in teaching me something about how to be a lawyer, but maybe more broadly than that.

JBG: And you did you say it was, Judge Walker, who introduced you to Judge Johnson in Alabama?

SRW: Burke Marshall.

JBG: It was. Okay.

SRW: Who was the former assistant attorney general for civil rights. So, I could tell you how that came about.

JBG: Please.

SRW: Many students at Yale Law School end up clerking for judges. I thought, ‘That’s something I would want to do,’ and to do that, you have to get recommendations from your professors, and I had had a class from Burke Marshall, on the First Amendment, and also another one, and I went to see him, ask him if he would recommend me for a clerkship, and he said, ‘I don’t write recommendations for students, for clerkships. It’s just not something I do.’ And I remember thinking, ‘Oh, dear, what am I going to do?’ I thought I had enough, but he was somebody I had hoped would help me. And then, he just paused and said, ‘There’s one exception. If you would like to go clerk for Judge Frank Johnson on the Eleventh Circuit Court of Appeals, I will write you a recommendation.’ And I already knew, I had learned at Yale Law School, that I was a Southerner. I just realised that was the case in all kinds of ways. I thought I was going back to the South anyway and, of course, I knew that my mother’s family was from Alabama. Judge Johnson was in Montgomery, Alabama, and I thought, ‘I would be delighted to clerk for Judge Johnson if I can get that clerkship.’ It was very competitive and there was no guarantee I would. And he said he’d be happy to do that. Of course, I did clerk for Judge Johnson. Interestingly, Burke Marshall came down and stayed with us in Montgomery, in really not yet the nicest house, probably, because I was young and kind of starting out. He had such strong memories of the work Judge Johnson had done, really to desegregate the state, and he wanted to come back and see it.

JBG: How long was that clerkship? Was that one year?

SRW: It’s a one-year clerkship.

JBG: One year. Okay.

SRW: It’s, sort of, a lifetime relationship, but it’s a one-year clerkship.

JBG: Okay. And it sounds like there would be so many components of that that would be, perhaps, really fundamental in shaping the direction of your career afterwards, but I’m curious: when you reflect on that one year that you spent with Judge Johnson, what stands out?

SRW: I don’t think I knew it at the time, that this was what I was learning, but, you know, since I was also a judge later, I am confident that his example of courage was something that mattered to me later. Now, you have to understand that Judge Johnson was, you know, at risk of losing his life, and certainly was, you know, ostracised by the community and encountered all kinds of difficulty doing what he did when it came to civil rights, so, there’s no comparison between what he did and what I’ve done. But I think courage is one of those virtues that sounds like a slogan, or it did to me. I didn’t think it was something that was that relevant. It sounded more like, you know, you’d need that on the battlefield or—I don’t know, it seemed remote to me. But in retrospect, I needed it, and he was a great example of someone who did what he thought was the right thing to do. That’s always in the context of—

you know, when you’re talking about law, you don’t just do what you think is right. You have to follow the law. That’s part of it. But he still would find his way to a good way of thinking about how he was going to approach what he was going to do, and he had the strength and, again, the courage to do that.

JBG: And what direction did your career take after that clerkship?

SRW: So, it’s funny, because he was very adamant that I do this, and he was right. I think he was not eager for me to go to law firm after clerking, and he thought I should work in state government, and ultimately thought I should work at the attorney general’s office. Although he had hoped that someone would get the governorship, in fact, that he, maybe, privately supported, he couldn’t—you know, judges can’t be overtly political. But it was somebody he knew well. That didn’t occur. I couldn’t work for the governor. The person he would have liked me to work for didn’t get elected.

But I did go to work for the attorney general and I had some big voting rights cases that I was involved in there, which was an interesting and important part of law. Probably the most important thing I did there was not bring a lawsuit but settle a lawsuit. There was one called Dillard v. Crenshaw County that I can talk about because it wasn’t when I was a judge, in which many, many smaller governmental entities, such as school boards and county commissions and others, cities—there were suits on behalf of a class, I believe it was of black plaintiffs who alleged that their voting rights were restricted in the state of Alabama, and I had a discussion with the head of the Civil Rights Division, which is where I worked, about what we should do about this lawsuit, and we both decided it needed to be settled. And that began a very long process of participating in some major changes in how office holders in smaller offices were elected in the state of Alabama. I think that case has been written about by scholars. It’s one that brought some major changes to black representation and politics in the state. So, I think I spent the most time on that. During the course of that, I met my husband and decided to stay in Montgomery, which is where he was from.

JBG: Wonderful.

SRW: And I guess I should add, after that, I practised law at a small private firm that let me doth both plaintiffs and defense work, which was a great thing from my perspective. So, I had lots of different cases. I suppose the one that probably got the most attention or recognition was a plaintiff-side case on behalf of quite a number of what we would have referred to then as poor school districts, disadvantaged schools throughout the state of Alabama that had very much substandard resources in all respects, and those would have included majority black counties, but also some other counties in the north of the state. And I spent a lot of time on that. [50:00] And then finally, I became a United States Magistrate Judge.

JBG: Yes. And that was in 1996?

SRW: That’s right.

JBG: Okay. And I’m curious if, as you were navigating those earlier years of your law career, being a judge was something that was in the back of your mind during that time, something that you were aspiring to.

SRW: It must have come to be in the back of my mind at some point. Certainly, clerking for Judge Johnson in that same courthouse where I became a judge gave me an introduction to what actually happened there, and it made me think, ‘Well, maybe I could do that.’ And it seemed to be work that mattered. And it matters, oddly enough, on, kind of, a micro-level, in a way, because although one may get involved in lawsuits that have much larger consequences – certainly Judge Johnson did – and change the legal landscape, the culture, the way people live, in a big sense, as time passed, I learned that there was much more work at what I guess would be fair to call a micro level, that is, case by case, person by person, and that’s maybe where I ended up by the time—you know, I did that work for 40 years, which is crazy.

JBG: Wow.

SRW: Is that right? 26 years as a judge. I’ve been in Montgomery 40 years. But many, many years. And that evolved for me, from the point where I think I may have thought, ‘Oh, I can decide cases that have a big impact,’ or whatever, you know, on a larger community, to realising that so often, where I was working and doing, maybe, the things that were the most important to me were case by case, even in the criminal system, which is work that you may remember, from what I said about law school, that I already cared about, that I’d learned to care about, from both some of Bob Cover’s writing and also from Joe Goldstein’s criminal law class. So, I came to really love criminal law in particular, even though I had lots of civil cases as well.

JBG: I know that there are constraints around what one can speak about with regards to one’s service as a judge, so, if you can share, in broad strokes, about what, reflecting on your nearly 30 years on the bench, was the most rewarding about that time.

SRW: When it’s framed as what’s rewarding, I have to think about it some more, maybe. I know what I cared about the most, as time passed.

JBG: Please.

SRW: I think I was disturbed—well, let me go back a step. Magistrate judges do all kinds of things, and it differs from system to system, but ours was a court where we did everything, from mediation to lots of civil cases by consent, to our own dockets of misdemeanour cases and then a tremendous amount of work on the felony cases that were overseen by the district judges. So, one of the things I began to realise is that, although, when it came down to sentencing, I could sentence only up to year in custody, I was working on cases in which the decision whether to detain somebody was one that I was constantly making, and that would be typically in a felony case, in which that detention could last for well over a year, maybe a couple of years or more. And then, I was also involved in a lot of decision-making about whether to revoke somebody’s release. And then, we were tied in on what we called supervised release, which was release after somebody served a custody sentence.

So, I began to realise how much that dominated my time and I did not love—I can say this, because judges are actually charged with talking about the law in this sense, though I can’t talk about individual cases, but I felt strongly that there were some great probation officers who really tried hard to do their job, and they were there to help us with those kinds of decisions, in part. But there were others for whom the system incentivised locking people up, basically. If you’re a probation officer, it’s so much more trouble for somebody to be released and for you to have to supervise that individual, because they’re probably constantly causing you difficulty. Some people don’t, but many do. They’re not passing drug tests, and getting into more trouble, and it’s just a lot of work.

And just a small thing that, for me, became a big thing, was to, sort of, swim against the tide of the default, ‘Yes, let’s just incarcerate somebody,’ and those incarcerations for several years, or sometimes even a few weeks or a month, had massive consequences for them and for their families, and those included, for the families, you know, a lost job that without the income from the family that might cause the children all kinds of issues, including custody issues, or deprive them of child support. All sorts of things can happen when you detain somebody, and it’s a much bigger issue than I think I understood at first, and so, it came to be something I worked very hard on. What alternatives could I find to detention? Detention is not only costly for the individuals who go through it, but it’s expensive for taxpayers. It’s much less expensive to supervise somebody on release than to pay for them to be incarcerated, and I think all of us know that there are issues about who is detained, who is incarcerated, and those were troubling to me.

So, I did a lot of work on mental health issues and on drug and alcohol issues, literally just trying to find people treatment options, trying to persist in the face of calls for the easy decision, which was to incarcerate, and learning, as time went on, things that probably were obvious to everybody else, but it took me a while to understand how important a job was, what some of the impediments were to getting that job: if you didn’t have a driver’s licence, what could be done in the community to help pay fines and get a driver’s licence back? How could somebody not just be sent to treatment, but be sent to useful treatment? There was not much that was evidence-based, and so forth, and I would really sit and try to work on that, work on it with probation officers and also work on it with my staff and with the district judges I was working with.

So, I guess that’s my answer, broadly. That came to be the most important thing to me, and I guess it was the most rewarding, in the sense that there were times when I could feel that what I did actually had made a difference, and I would never have imagined that that was the career I was heading into. It’s not obvious at first that that’s what you’ll do. But that was rewarding. And then, I think, maybe another piece of it is back to the civil work and the other more criminal work that was more scholarly, just the effort to think clearly about something and to think as dispassionately as one can, even though the notion that we’re completely unbiased is silly. But to try to make the right decision, that mattered to me, and also to explain it well, if I could, mattered to me, and to explain it in a tone that was appropriate, that was not just histrionic and screaming at people, but just setting out, contributing to this culture of argument in a way that was helpful and positive.

JBG: Thank you for sharing that. Are you retired now, Judge Walker.

SRW: I am, yes.

JBG: When did you retire?

SRW: It’s been a little more than two years. So, I retired on 1 June, I guess, [1:00:00] a couple of years ago.

JBG: Well, congratulations.

SRW: Thank you.

JBG: In our last conversation, you shared a little bit about the Sew Their Names Project and the history of that project, and I was wondering if you would mind sharing about that.

SRW: I’d be happy to tell you about it. The project, which I’ll come to in a minute, grew out of, sort of, a broader encounter. So, you know, I’m in Montgomery County. The next county over is Lowndes County, and I knew that Lowndes County was where my mother’s family had come from. There were also family members in Morgan County. Lowndes County was – and Montgomery County too – a hotbed of slavery. This was the Black Belt of Alabama, where the big plantations were, and the vestiges of slavery remain here and they are palpable. They are real. They have not, you know, gone away. That’s the history of this area. And I grew up knowing that my family had enslaved other people, but that was it. I didn’t know, really, much else about that. I did know from my mother that her great-great-grandfather, whose name was Reverend David Lee, had been a Baptist preacher in Lowndes County – again, the next county over – a county that at one point, I think, was ranked the 12th in the number of people who were enslaved, or something of that kind. It’s a cotton plantation area, very rural – still is – and it’s also majority black.

That’s just the background. I was in court one day about five years ago, maybe a little bit more, and a lawyer came before me who had the name David Lee, and I recognised that name as being the name that of my great-great-grandfather in Lowndes County, knew very little other than that about him, other than what she told me. And I remember thinking, as I left court, ‘I wonder if that person is related to me,’ and I hadn’t thought about that name. I’m just going to do what you do: I Googled it. And what came up, to my surprise, was an application for listing on the Alabama Historic Register, the equivalent of that, for my great-great-grandfather’s church. And I know I had driven by there, years ago, when I clerked, but I hadn’t seen it since then, and I knew it was an antebellum structure, a very plain old church, and I didn’t know whether it was even still standing, but here was this very evidence that it was still standing and that someone had taken the trouble to apply to put it on the Register. So, I read the application, and when I did, I realised—well, I read that my great-great-grandfather had been a slave owner and had had a church which had a slave gallery. The slave gallery is typically a balcony. There are other separate sections that were used, but typically, a balcony, where enslaved church members were compelled to worship.

Well, I didn’t know that and it came as a surprise to me, though I knew that some of those still existed. I didn’t know whether there was still one in his church. But I just hadn’t been aware of it. And I also learned from reading that, that my great-great-grandfather had been one of, I think, 14 or 15 individuals who represented the Baptist Church in Alabama in, I want to say 1844 – that may be right, or 1848: one of the two – in Augusta, Georgia at the conference where the Northern Baptists and the Southern Baptists split over slavery. So, he had represented Alabama, and that meant, I knew perfectly well, what his position had been. So, when I read all of that, I thought hard about, what did that mean, and was there something I should do that would grow out of that? Did I have some obligation? Did I have, maybe, any way that I could recognise what my family’s role had been, and maybe even be of some help? I think I had, sort of, a vague idea of what to do, which was—I didn’t know what to do. But I did think that I hadn’t seen, for some many years in Alabama, much outreach around that subject, certainly not from the white community.

So, I sort of took a deep breath and, at some point, sent an email. I could see that a black church owned my great-great-grandfather’s church at this point, and I thought that was interesting, and I could see the name of the pastor and his contact information. His name was Dale Braxton, and I just wrote him an email, I think, and I asked him if I could come and meet him and then I could see the church. And I think now, I understand from Dale, that his first thought was, ‘This is not at all what I would like to be doing.’ He had just come back from a visit to Africa and, specifically, he had been to what’s called the Door of No Return, and he’d seen something about the church’s involvement in supporting slavery on that side of the Atlantic, and I don’t think he was in any mood to talk about slavery, and certainly not to welcome the great-great-granddaughter of an enslaver from his area. But he’s a very kind person and a very gracious person, and that’s not what he said when he replied to the email: he said, ‘Absolutely, please come. I’d be happy to show you the church.’ So, I went to see it, I think with some naivete about what this experience would be like for him, and, you know, in retrospect, I feel like I was somewhat smug, almost, and probably inappropriate, in my telling him about that heritage and my interest in acknowledging it, at least, and seeing whether there was something I could do to help there.

But again, he was very gracious, and I think he, kind of, sized me up, and then he finally said, ‘You now, I’d kind of like to restore this building, and I wouldn’t mind having some help.’ And I thought, ‘Well, I can write grant proposals.’ So, that’s what we started doing. I started writing grant proposals to the Alabama Historical Commission and looking for funds, not just to restore the church, but to tell the story of the church’s support for slavery, which I had not known a lot about. And at some point, I applied for a fellowship, with his support, at the Gilder Lehrman Center for the Study of Slavery, Resistance, and Abolition at Yale, so I could research the history of that church, and also did work at the archives of the Baptist church, which were at Samford in Birmingham. And when I was sitting at the special collection at Samford, I began to look what they called the ‘church books,’ which were records of—the Baptists were just unbelievable record-keepers. They wrote down everything about their conferences, about their membership. In some respects, in this period of time, they were on the frontier, and the churches would get there before the government would. And so, a lot of regulation took place and a lot of discussion about behaviour, and I was reading these accounts of those lives then, and I kept seeing membership rosters, and it would have – because there was segregation everywhere, including in the written materials – whites on one side, blacks on the other side.

But there were black members of these churches who were enslaved, whose names were there, and the names were first names and then ‘Owned by,’ and you’d have the plantation, or ‘Property of,’ but those individuals were tied to specific churches in the area. My great-great-grandfather had been the moderator of – it turned out, I didn’t know this – the most powerful [1:10:00] Baptist conference in the state, that was frequented by—the members included Supreme Court justices and governors, and so forth. Anyway, I should say that those churches made up the Alabama Baptist Association – it was about 30 or 40 churches at the time – and I could see the names of enslaved people linked to specific churches and specific owners, and I thought, ‘I’ve never seen this before.’ I’d looked at the census documents, but they’re not listed by name there: it’s just property records, number and gender, and so forth.

So, I brought these back to Reverend Braxton, and to my law clerk, who was helping me, and we started talking about the question of whether there was something that maybe should be done to commemorate these people who had been, basically, erased from memory. The descendant community locally did not know those names and were completely unaware of the records. And so, that brings me to the Sew Their Names Project. At some point, that church, which is in Mount Willing, a small town in Lowndes County, Reverend Braxton’s church, had a quilting project, and it occurred to us that a way to commemorate some of these names would be to sew them into quilts. And this was at the time of the sort of racial reckoning after George Floyd’s killing, and saying their names, sewing their names, saying their names, at least, had become a way to honour the survivors and victims of these kinds of racial issues which, of course, had continued in a different form.

So, we started a project that brought together both whites like me, who were the descendants of slave owners, and the descendants of enslaved persons in that area, to get together to sew their names, to hear some of this history of the church and to work together to create something that was very unusual for Alabama, which was some sort of commemoration of these individuals. This is a landscape – I’m back in Alabama right now – where there are Confederate memorials everywhere. So, you can read the names of the Confederate dead wherever you’d like to read them. Well, you know, we honour people who persisted against the odds and who worked tirelessly and were remarkable in what they could achieve, and enslaved people were those people, but they do not appear on the monuments here. So, the idea came about of a different kind of monument, one that’s not stone and brass or a man on a horse, but this human-scale fabric quilt memorial that is just a very different, kind of, counter-memorial to those sorts of memorials. So, I guess, so I don’t go on about it forever, the end of the story is, that has, I guess you could say, taken off a bit and there are a couple of quilts that have been made, there are some others coming along, and they’ve been shown locally, in museums. They’re travelling, I think, as we speak, to the Black Belt, for some projects there. There’s a video about this. There’s an article about this coming out soon, and it has acquired some interest. I think that people in Mount Willing might say that it has made a difference to them. And they would do better speaking for themselves than my trying to speak for them, but it has, I think, been an experience that they’ve enjoyed and have been proud of, and I’m proud to have participated in it and grateful for the opportunity.

JBG: Thank you so much for sharing that. What a meaningful project, and I really, really appreciate you sharing that. Thank you, Judge Walker. I’m conscious that during your, I would imagine, very full days during your professional career, you have been so wonderful to stay in contact with the Rhodes community through your selection service, I have in my mind specifically. I know that that is such a devotion of time and oftentimes a labour of love for those who participate, and I was wondering if you would mind sharing what inspired you to stay connected with the Rhodes community in that way.

SRW: I was so happy to be asked. I don’t think I expected that. Very early on, when we came back from Oxford, and there were so few women who had had the Scholarship, the Rhodes Trust as represented in the United States – and I’m sure this was backed by the people in England – I think was at great pains to put women on the Scholarship committees. And it was, kind of, a fabulous experience for me, because they would send us all over the place. I can remember being sent to Massachusetts and to South Dakota and Mississippi and quite a few other places, either to be on what at that time would have been state committees or district committees; that system has changed now. And I ended up being secretary for the Alabama part of the Rhodes Trust and for those selection proceedings, and I think altogether, all of this must have been 25 years.

But, I mean, it was just such an enjoyable experience. It was so much fun to meet people who had been to Oxford like I had. But also, it mattered to me a lot to do the part that I could, at least, to make sure that that scholarship still was accessible to people who, like me, I think—I mean, I just wasn’t born to it. It wasn’t something anybody expected I would do, least of all me, and yet, I felt I had a shot at it, and other people ought to feel like they did and to be welcomed and asked questions that let them reveal themselves, if that makes sense, that were not questions that were there to intimidate or to cross-examine, but were, sort of, open-ended, thoughtful, if possible, questions, that let them show us who they were. And that’s an enjoyable process. It’s not where I think you think, ‘Oh, I’m wonderful at this.’ I don’t know that I felt that way, but I wanted to try. So, that mattered to me, and over the years, I met, I think, some remarkable people in that process, including people we didn’t choose, obviously, but it also gives you a sense that this is not the only avenue, and that’s important as well.

JBG: Lovely. Well, thank you so much for that service, Judge Walker, to the community.

SRW: Well, I think I should add, I do appreciate the Rhodes Trust’s work over the years to open that scholarship up, in a variety of ways. It’s important to do that, and I don’t want to fail to acknowledge—I mean, I wasn’t the only one trying to do that work or even attempting to help with that. There were lots of people hell bent, more than I think others realise, on making the experience as open as possible to different communities.

JBG: Wonderful. So, it is 2024 and you have an incredibly accomplished career and these wonderful initiatives that you’re involved in, and I was wondering if you would mind sharing a little bit about, at this moment, what motivates and inspires you today.

SRW: So, after years and years of doing art as, sort of, a side pursuit, I’m pretty much all in [1:20:00] to trying to make that what I do, which is new, and it’s gratifying, and also a little bit frightening, to start over, but I think exactly what I ought to be doing. I didn’t want my life to just get smaller and smaller as I got older, and I thought the new challenge of trying to do something well that I haven’t really had time to pursue was something I really wanted. And I guess I should say what I’m doing, but I came to be interested in woodworking, I guess, in a basic sense, meaning that I’m working with wood. And I loved the tool-using and the problem-solving part of that, because I find it – this is the most jaded, empty term – empowering, but it is empowering. It turns out, you can build stuff and it’s possible to make tools that I didn’t think I’d want to work with do what I’m hoping they’ll do and, sort of, not screw that up and, you know, having a table saw is cool, instead of my thinking, ‘Oh, I never would use that tool.’

So, some of that has been just fun, but my interest really goes back now, I think, to when I was the youngest, which is when I was, I guess, that barefoot kid running around in the woods out in Tennessee. My father, he didn’t use power tools. He did a little bit of building, but it would be sheds for the garden. He used a hand saw, he used a brace and bit. But he always thought he could build something or do something, and I think I learned from that. He also a cared a great deal about birds and about trees and about gardening and all of those things. And so, I have, kind of, merged, I guess, some of that background, some of that interest, into thinking about, now, how to—I’m going to use words I don’t think are the right ones, but how to make visible – or to pay attention to, perhaps, is a better word – what I think of now as this vanishing natural world, and to do that with art, or some might say fine craft, or whatever.

So, what I’m engaged with is what I guess would be called decorative arts and using the techniques of the late Middle Ages, in particular, the beginning of the Renaissance, and even the later Renaissance, bringing those techniques. So, those would be gilding, using egg tempera, using true gesso, pastiglia, sgraffito, some of the things that those people used to celebrate the things they valued the most – most of those were religious – to look at the natural world now. And something I’m particularly interested in is the traditions of ornament from that time, where you might see a laurel or acanthus or, you know, decoration using the natural world they were familiar with, I would use something like ragweed or beggar’s lice, or the things that I saw, growing up in the fields and the woods, many of which – not those two particular things – are now vanishing. So, sort of, changing the ornament from the old world to the new world, but thinking about, you know, quite frankly, what we’re losing, or just thinking about how to see what’s around us better. And I use wood most commonly, always native, and something I might find on the curb, you know, so, it might be, rather than the walnut and the cherry you can buy in the wood store, you know, dogwood or redbud or poplar, you know, common woods, whatever is around.

That’s a rambling description of what I’ve been doing, because it’s a rambling enterprise whose focus I’m still working on, I think, but I love it. It’s just a wonderful thing to, sort of, start again and do something different. So, that’s what I’ve been doing. The last thing I should say is, right before this interview, I spent seven days in Connecticut, making a Windsor chair with hand tools. My husband, who went to Washington and Lee, happened to like Windsor chairs, and he wanted one, and I thought, ‘Maybe I can make that.’ So, that kind of thing, I love, even though it’s not central to—I don’t think I’ll be making chairs from now on, but just the opportunity to go back to classes and to think of doing things I didn’t think I could do, I find just really worth doing. And it might be that the Rhodes Scholarships sent me on my way for that, as much as anything, even though I didn’t study art at Oxford. It certainly helped me think about the wider world and think about whether, maybe, I could do some things that were more difficult than I thought and less likely for me to do them than they came to be, hopefully.

JBG: Lovely. Thank you for sharing that. Would you like to share, Judge Walker, a little bit about your family?

SRW: My family? Sure. So, again, my parents, I mentioned before where they were from. My father was a smalltown banker. He went to Columbia, and I can’t remember where else. So, he had a good education, but was never a literary guy. He became a trust officer in a bank and, to me, is, kind of, the classic fiduciary, ‘fiduciary’ being a term we would use in law, somebody who just took care of people in his job. It was, I think, frankly, widows and orphans. He did that work, looking after people for whom a family member had died, and he was taking care of their estate and looking after them. My mother was a, she would have said, homemaker. She was a big influence on me, in a lot of ways. And she taught speech, you know, drama, debate, that kind of thing. I did debate. I did oratory in high school. But I think the thing that influenced me the most was that she had polio before I was born, so, she used a wheelchair all of my life – I never knew her any other way – and was very early in working on access, architectural barriers and access issues, back when the movement for disability rights was really focused on the physical environment.

And I haven’t mentioned that before, but it was a big influence, I think, in my going to law school and thinking about doing public service. And I should have mentioned it, because I saw what she did in advancing that particular cause, and that included her calling up the mayor of the town and saying she wanted him to ride around in a wheelchair for a day and see how it felt, and figure out whether he could get into a car, into a bathroom, or up a curb to shop, and I think he did that, and he thought afterward, ‘You know what, it’s pretty hard,’ and things changed in that town after that occurred. She was very courageous in taking on those issues and did it without a legal background, without the help I had in, I guess, being taken seriously, and I wish she could have been a lawyer, frankly. She would have been a good one. So, family wise, there were my parents. Again, also very involved in the church. And my mother had done some work that was interracial, in the sense that it was [1:30:00]—I can’t remember the name of the organisation, I think it was called Church Women United, and she was very involved in getting women together who were women of colour, and white women, and that probably had an influence on me as well. Two brothers and one sister, all of them, as I think I said, very smart, good students.

I’m married to Dorman Walker, who is a lawyer still. He’s going to retire, I think, in a few months, and he is distinguished for many things. He is a really good cook. He’s a very good reader and thinker, with all kinds of interests. I’m eternally grateful for his support for almost anything I’ve wanted to do, and there is more that could be said about it, but I think his interests run to architecture, art, cooking. I really think he lives in his head a lot and has incredible skill at understanding the visual world and responding to that, and I find that, sort of, constantly inspiring, if that’s the best term. My daughter – her name is Lanier – she is at present finishing a PhD at the University of North Carolina, in early modern literature. She went to Harvard before that and was an English major but did a lot of work in art history. And she has recently married her husband, who has just finished his PhD in mathematics. His name is Andrew Adair. We’re crazy about him. We’re crazy about both of them. They are remarkable people who are dear to both of us, and we’re just so grateful to have that family. And that’s not enough to say about them, but they wouldn’t want me to keep going on, I’m sure. The last thing I’ll say is, one of the reasons we stayed in Montgomery is because of extended family on my husband’s side, and we’ve just visited with all of them at a family wedding, and we have just the most remarkable group of in-laws and nieces and nephews and grand-nieces and grand-nephews, and we’re really fortunate, and that’s something we spend a lot of time on, and people we spend a lot of time with. So, very, very lucky, I think.

JBG: Lovely. Wonderful. Well, Judge Walker, as we move to the final section of our conversation today, I would love to ask you a few questions around the Scholarship, the first being, what impact would you say that the Rhodes Scholarship had on your life?