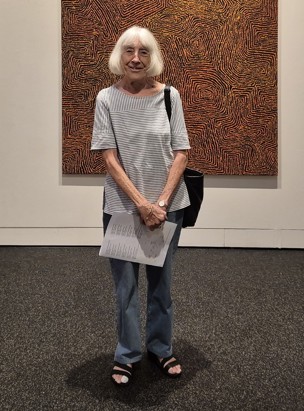

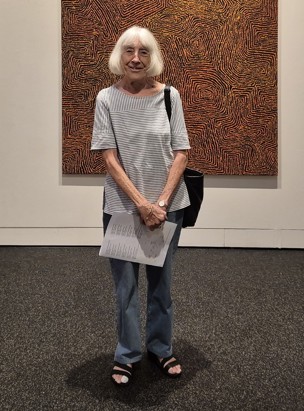

Susan Kippax

Rhodes Visiting Fellow & Lady Margaret Hall 1970

Born in Narrandera, New South Wales, Australia, Susan Kippax studied at the University of Sydney, taking her undergraduate degree and beginning her PhD in social psychology before being elected as the first woman Rhodes Visiting Fellow. After two years in Oxford, she returned to Sydney and took up a post in the Department of Psychology at Macquarie University. There, she helped to establish the National Centre in HIV Social Research, which opened in 1995 and moved to the University of New South Wales in 1999. In 2000, Kippax was elected Fellow of the Academy of Social Sciences in Australia, and in 2019, she was appointed an Officer of the Order of Australia in recognition of her distinguished service to education and community health, particularly through her research into HIV prevention and treatment. Her co-authored works include Socialising the Biomedical Turn in HIV Prevention and Sexual Adventurism Among Sydney Gay Men. This narrative is excerpted from an interview with the Rhodes Trust on 5 September 2024.

‘I was actually quite surprised when they offered it to me’

I spent the first five years or so of my life in a small country town in New South Wales called Narrandera before my family moved to Sydney. As a family, we lived between Sydney and Wollongong, on the coast, and I spent a lot of time in the water, learning to surf and swim. Then, when I was about 20, my father, who was a banker, was transferred to London, so I went with my parents there. I saw a lot of Europe, hitchhiking around, and I loved it. When we came back to Sydney, I was ready to go back to university. I couldn’t afford to go in the daytime, so, I worked and went back to study at night, enrolling in the social sciences. We had a very good lecturer in social psychology and the way he talked about the social world made me realise how important it was.

After my honours degree, I started a PhD, using my mathematics to measure social attitudes. I hadn’t quite finished my PhD when I saw this advertisement for the Rhodes Visiting Fellowships. In those days, only men could be Rhodes Scholars, but the Fellowships were open to women, and I was the first. I was actually quite surprised when they offered it to me, because they had flown three of us over for interviews in Oxford and the other two candidates had both finished their PhDs. I thought they would be preferred, but I was offered the position and I was very grateful to take it.

'It built my confidence enormously’

I think what was unexpected for me about Oxford was how formal the English were, particularly at college. But, once we’d got used to each other, we were all very friendly and got on well together, and it was a very pleasant experience. Lady Margaret Hall at that time was an women-only college. Much of Oxford was still very male-dominated, and being in a female space built my confidence enormously, and that was very good for me. I met many people and I’m still very good friends with a number of them.

I’d already been tutoring and doing research for a couple of years, but Oxford was actually a very good introduction to my full academic career. I learned quite a lot, mainly about tutoring, but also how to read lots and how to use a big library. The libraries in Oxford were amazing, and it was a good place to work. Tutorials were such an interesting way of teaching, and the students were very bright. At that time, most tutorials were still one-on-one, and the tutorial would be a discussion of how an undergraduate had approached the problem in their essay. It was something students had to do of and for themselves, and I enjoyed that style of teaching very much.

‘The research we were doing was actually having a huge impact’

The Principal of Lady Margaret Hall said that I should stay in Oxford, and that they would offer me a job, but even though I enjoyed Oxford, I had always been absolutely certain that I wanted to go back to Sydney. It’s a fantastic city and one that I really love. I got a job at Macquarie University in 1972, and I stayed there until 1998.

In the 1980s, at the height of the HIV/AIDS epidemic, Australia had established HIV research centres in epidemiology and in biology. I began by doing a little bit of work with people from the centre in epidemiology, but it became clearer and clearer to me that in order to change people’s attitudes and their practices, we needed to work in a social way, because people do what other people do. Soon, I was doing nothing other than HIV research. I helped establish the centre for social research, and ended up becoming director of that national centre.

I worked very closely with the gay community. They clearly wanted to change their practices, and they clearly wanted the death rate and the infection rates to go down as quickly as possible. I’m not gay myself, and I wasn’t sure how the gay community would respond to researchers who weren’t, but we were absolutely welcomed with open arms. We gave a lot of talks and we also held small group meetings and listened to what people were saying about their lives. We worked hard, but it wasn’t hard work, because it was extremely interesting, although it could also be very sad work, when colleagues of mine died of HIV, and many did in those days, of course.

Engaging with the community was absolutely central. Unless you do that, you’re not going to do very well in changing attitudes. You have to work hard in getting people to be well informed and to trust you and to trust the research. If that doesn’t happen, you’re not going to get great change. Social research is often seen, especially in English-speaking countries, as taking second place to epidemiology and biological research, but I think what became obvious to everyone, even the biologists and the epidemiologists, was how important social research was, and how it was to be able to communicate with people as people. You couldn’t just talk down to them because you were a researcher: you had to get them really engaged in what you were doing and why you were doing it.

All of a sudden, we began to see real changes in behavioural practice, and that was very rewarding. Condoms just became the norm, and people used them all the time, particularly in the gay community, where, in Australia, over 80% of infections were. I’d worked in other areas of research, but it was exciting and exhilarating to realise that the research we were doing was actually having a huge impact. As a result of the research going on across all three centres, the rates of infection began to fell rapidly. In Australia, we were very lucky to be well-supported and well-funded. The university supported us very strongly, and the Commonwealth of Australia funded the three big research centres. The money flowed, and I think to great effect, because people realised how important it was to get this under control. The health minister at that time was also very supportive of the centre and very well-informed, and that made a big difference.

I worked at the centre until I retired in 2007, by which time, we had moved to the University of New South Wales. Over those years, we built an international reputation and held many international conferences, including in the UK, the US, Canada, France, Japan, Jordan, Norway and South Africa. I co-edited a number of journals in AIDS studies, and in 2003 I was awarded a Yale Visiting Fellowship at the Centre for the Study of AIDS in Pretoria, South Africa. That was extremely interesting work, because the number of cases was horrendous. The research itself was fairly similar to what I had done in Australia, and it was very interesting to see, in all the countries I worked in, how similar the responses actually were.

I don’t do very much academic work now, but the centre I started still exists. It’s now called the Centre for Social Research in Health, and it does a lot of good work in a range of areas. I continue to believe that the social world is really important. People live and communicate in the social world, and social research is central to how we understand human behaviour.

‘Keep those communication routes well and truly open’

One of the things I’ve learned over the years is how important discussion is for academics, and how important it is to form relationships with people who are reading similar things to you but who may not always agree with you. Being an academic is not just locking yourself away in a library. It’s important to engage, both with other academics and with your students. Students often have great insights into things, because they’re coming at them from a different background.

So, if I have any advice, it’s to keep those communication routes well and truly open and use them to the best of your ability. Engage with people, listen to people, and have good disagreements. I don’t mean fights, but good disagreements and good arguments, because argument of that kind is so valuable.