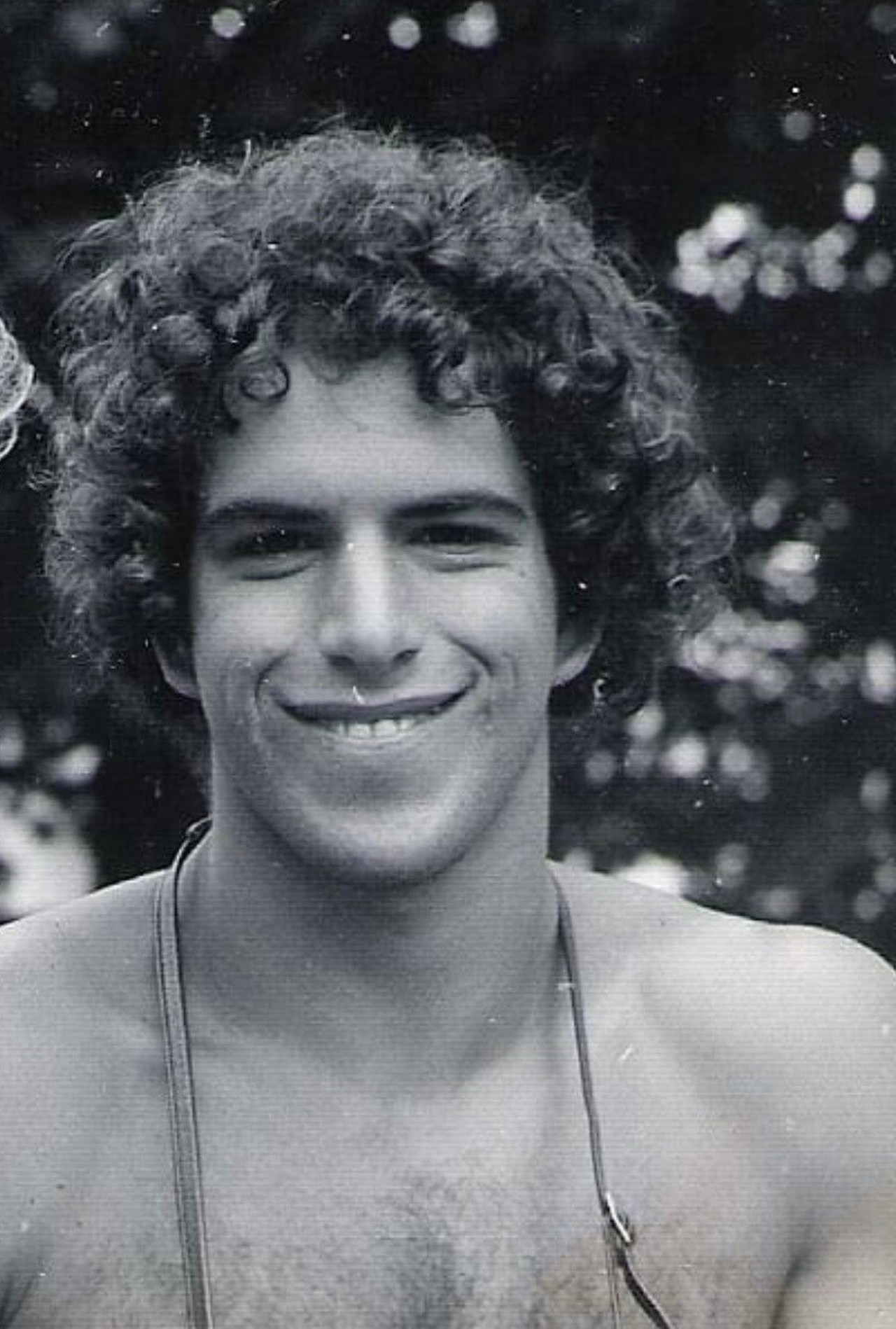

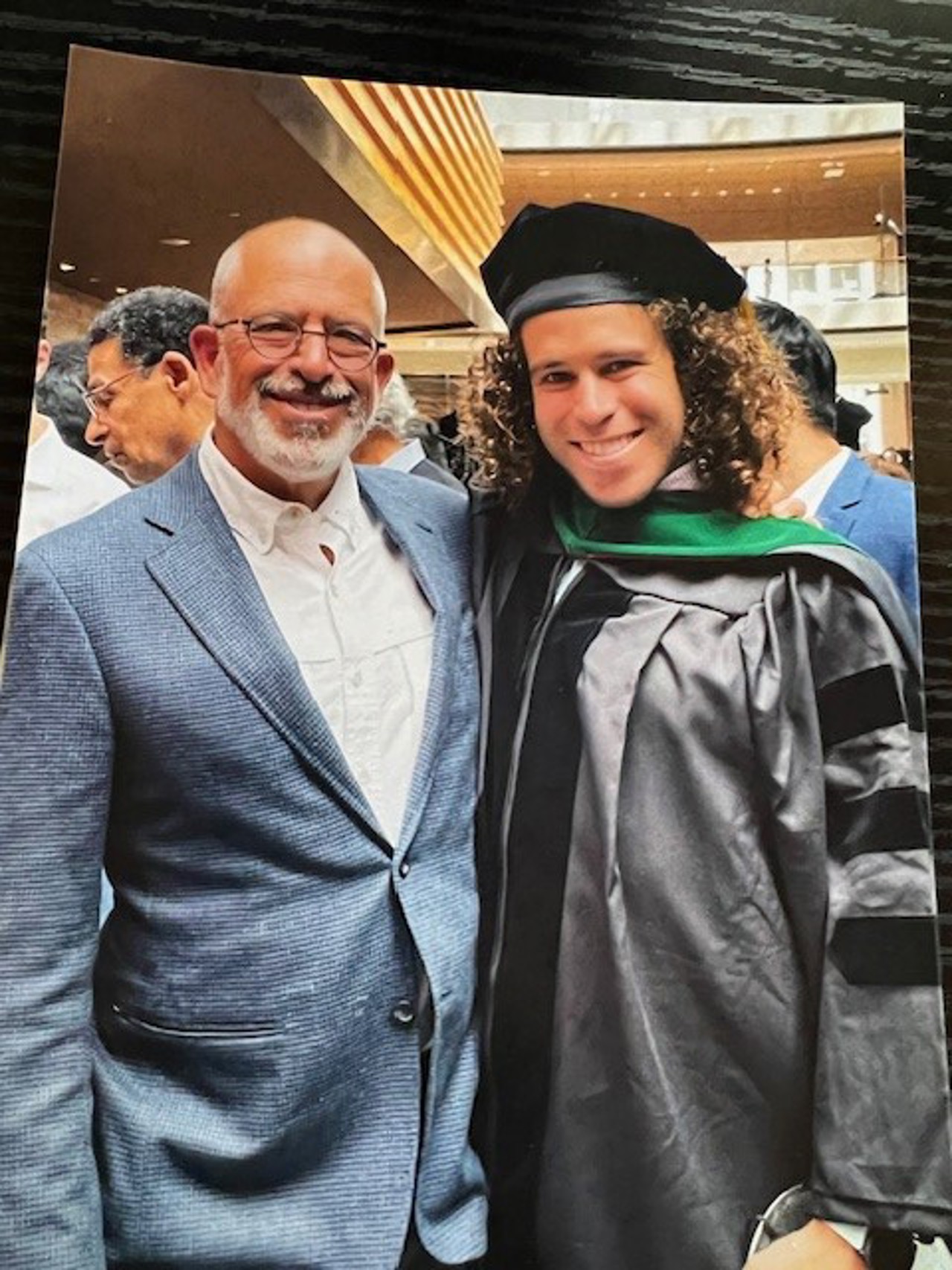

Born in 1954 in Brooklyn, New York, Steve Holtzman studied at Michigan State University before going to Oxford to read for a BPhil in philosophy. After Oxford, he worked with the state government of Ohio on technological innovation projects before moving into biotech and founding DNX Corporation, the first transgenic animal company. Holtzman went on to be early leader of Millenium Pharmaceuticals and then founded Infinity Pharmaceuticals, Inc., before joining Biogen, Inc. and leading eight new drug approvals. From 2016 to 2020, he was CEO and then strategic adviser at Decibel Therapeutics. He continues to work with young CEOs in biotech and is also a Trustee of Berklee College of Music. Holtzman has supported the Rhodes Trust in many ways, including through his service on selection committees for the Rhodes Scholarship. This narrative is excerpted and edited from an interview with the Rhodes Trust on 21 August 2024.

Steven Holtzman

Michigan & Corpus Christi 1976

‘The most influential thing in my life’

I had a canonical, New York City, street-kid kind of upbringing. My father’s parents had come over to New York around the turn of the twentieth century as part of the immigration of Jews from Russia and Ukraine. My mother was born in Cuba, and her parents had come to Brooklyn when she was seven years old. Neither of my parents graduated from high school, and they met at the New York World’s Fair of 1939, where my mother was a dancer in the Cuban Pavilion. She was part of a touring dance troupe of three couples, and when her partner left the troupe, my father said, ‘I can do this,’ and became a dancer too. I have very strong memories of Sunday nights in our small apartment in Bay Ridge, Brooklyn. The furniture would be moved against the walls and the Victrola was on with Cuban music and there would be 30 people dancing in the living room.

Bay Ridge, Brooklyn was a very diverse, working-class community. We all played on the street, football or stick ball, or even roller hockey with the sewer cap as the goal. I went to the local public schools through junior high school, and then I went to Stuyvesant, one of the three public high schools that were for primarily math and science and were entrance by exam only.

Then, when I was 16 years old, I went to work at a summer camp as a pot-washer, and it was perhaps the most influential thing in my life. This was a camp organised and run by people who included several Quakers, and it was non-competitive, non-sexist, interracial and highly arts- and music-oriented. That’s when I discovered there was a whole piece of me that wasn’t about science and math. It was the most influential thing in my life. Not long afterwards, a group of us started Shire Village Camp on the same principles, and it’s still going strong today. We designed and built two buildings, I ran the whitewater canoeing programme and would take kids out on trips. I often think that was my first startup! It really resonated with me to be able to release or cultivate other people’s creativity.

On applying for the Rhodes Scholarship

I chose Michigan State because it offered a mix of a pre-medical programme integrated with studies in the history and philosophy of science. Plus, I was a National Merit Scholar, and Michigan State was aggressively recruiting. My father drove a cab, and I was very fortunate that the New York City taxicab union had a scholarship, which I won.

I started off in a pre-med track, but one day, in a three-hour anatomy exam, I finished up in 45 minutes and just walked out of there and dropped every single one of my science courses. I didn’t see how I could exercise any creativity within that kind of science education, though now, the love of science I have is just incredible. I switched over and took courses on intellectual history, and I did independent studies in various areas of philosophy and ethics. Wittgenstein and philosophy of language became a huge area of interest for me.

I was going to go to graduate school in philosophy, and then the Honours College at Michigan State suggested I apply for a Rhodes. To me, Rhodes was Bill Bradley (Missouri & Worcester 1965). I said, ‘Me, a Rhodes Scholar? You’re joking.’ But I made the decision to apply, mostly to force myself to write a personal essay that I could also use for graduate school applications. I had no sense at first of just how stiff the competition was, but that changed by the time I got to the final stage, and then I completely blew the first interview. They called me back in for a re-interview and said, ‘Mr Holtzman, you seemed nervous during your first interview.’ I said, ‘Fuck, wouldn’t you be?’ and they all cracked up, and after that it was totally relaxed.

‘For the first six months, I was absolutely miserable’

I went over to Oxford on the boat with the other US Scholars. I was intimidated by them and – defensively, I guess. It felt like many of them had been groomed their whole life for this. I have to say, my first six months at Oxford, I was absolutely miserable. The food was horrible, it rained pretty much every day, and the people I met seemed to be the kind who would take their intelligence and use it as a bludgeon to put people down. Also, the predominant movement in Oxford at that time in my area of philosophy was preoccupied with formal semantics. I just felt very isolated.

But in the spring term, things really opened for me. I started to travel, to Greece and then all across Europe. That was also when I began to find friends in Oxford who are still dear friends to this day, including among my class of Rhodes Scholars. It turned out, they had been just as intimidated by me as I was by them. I also began moving away from pure analytical philosophy, so intellectually, things really started to gel. That was the time I started to realise that my major interest was in creating environments where people could really thrive. That came about, believe it or not, because of a Sunday morning game of touch football a bunch of us started. There was such a wide range of different skills and abilities, and I’d find myself, during the week, thinking about each of my friends and players and designing plays so that each of them could succeed.

‘Magic Johnson is my model for the perfect CEO’

By the time I finished the BPhil, I knew I wasn’t going to be a professional philosopher. I moved back to the US, to Ohio, because my girlfriend at the time had just got an academic post there. I started working for the state government, and I got assigned to staff the small business and economic development committee in the state legislature. It was a tough time for that region: industry was closing and there was a desperate need for technological innovation and job creation. I wound up working with Dick Celeste (Ohio & Exeter 1960) when he became Governor of Ohio, and I created the Thomas Edison programme, bringing government support to university-industry collaboration. In a way, that was my second startup.

My shift to biotech came with my fascination for the recombinant DNA revolution that was getting going at that time. I worked with a scientist at Ohio University, and we created a company to collaborate with the university on transgenic animals. That company became DNX. We worked across several areas, but particularly looking at animals as potential producers of therapeutic proteins for use in pharmaceuticals. Running a company, I had to teach myself everything, from the principles of DNA technology to accounting, to patent law. In all of that, what I’d learned at Oxford was crucial, and that was to ask yourself, whatever you encounter, ‘What is interesting about this? What do the people doing this well find so interesting about it?’

Across my many roles in biotech, at DNX, Millennium, Biogen, Decibel, I’ve aimed to keep that fundamental interest in and respect for what other people are doing. When you agree to lead people, you’re there for them. You must have empathy. It’s like being a player-coach, and I would say Magic Johnson is my model for the perfect CEO. Whatever I do in life, whether it’s leading summer camp, playing touch football, or building cross-functional teams in companies, I love creating environments where people can flourish.

On Innovation culture

Innovation culture on a drug discovery team, or any team, is analogous to improvisation in jazz. Jazz is deeply, deeply structured, and it’s that understanding of the discipline, to your bones, that gives you the basis for improvising with meaning, as opposed to just noise. Furthermore, if you look at typical classical training, it was not ensemble-based. Yes, they’ll play in an orchestra, and maybe there will be string quartets, but it’s not the same as jazz, which is largely ensemble. Yes, you have your individual excellence. You step out, you’re acknowledged. But you’re intrinsically playing off each other. The classic call and response, alright?

‘Find your voice’

For me, the major lesson from Oxford was that the only limits there are, are the limits you place on yourself. I came to see and feel that the entire world, not only geographically, but also of culture and thinking, should and can be part of my ordinary life.

To today’s Rhodes Scholars, I would say, find your voice. There’s a lot of noise out there, and you need to find your vocation and your own joy. Over the years, I’ve come to realise that joy is about being happy in the context of interacting and growing with other people and doing that in pursuit of something that is meaningful to rest of humanity.