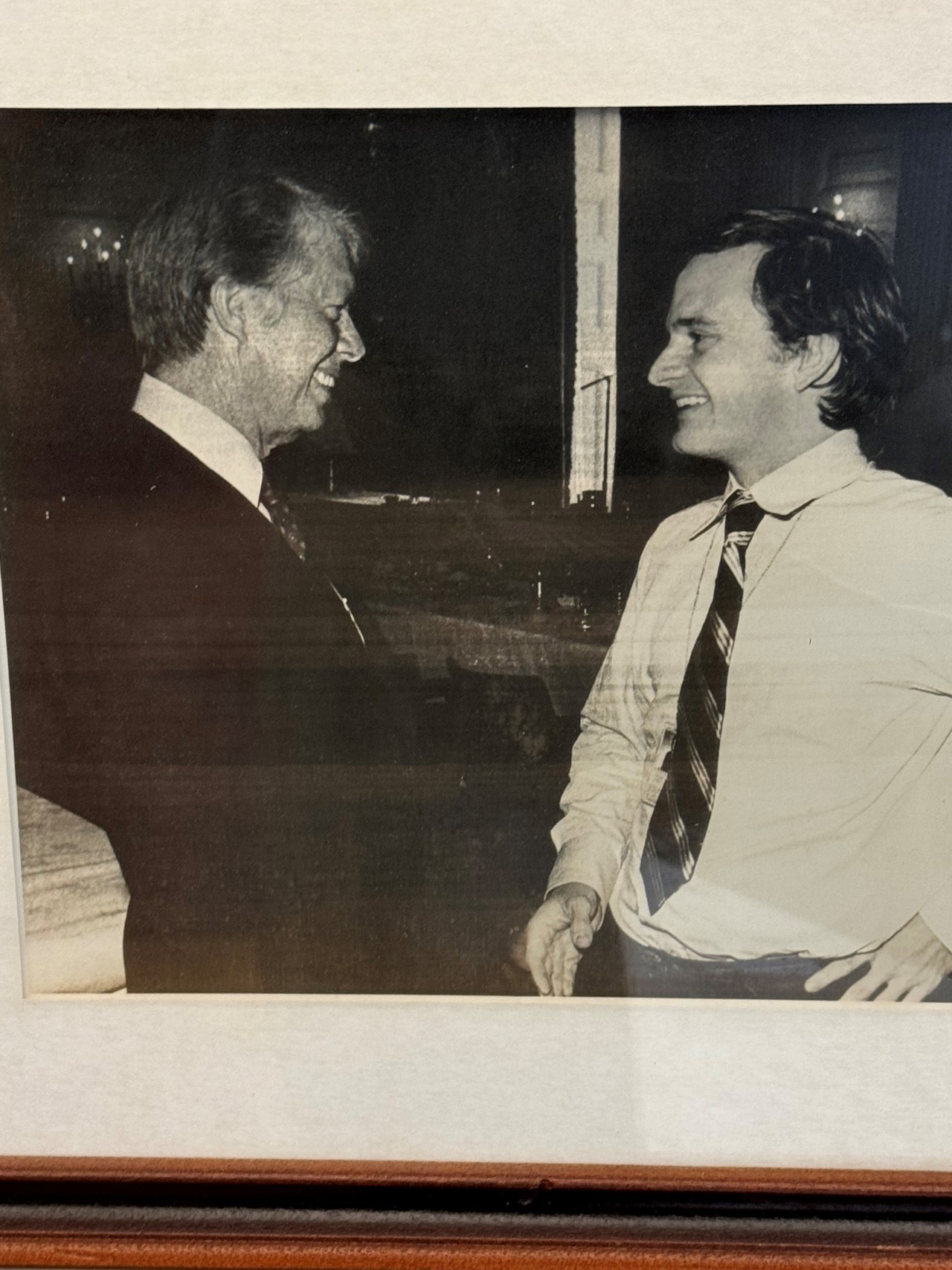

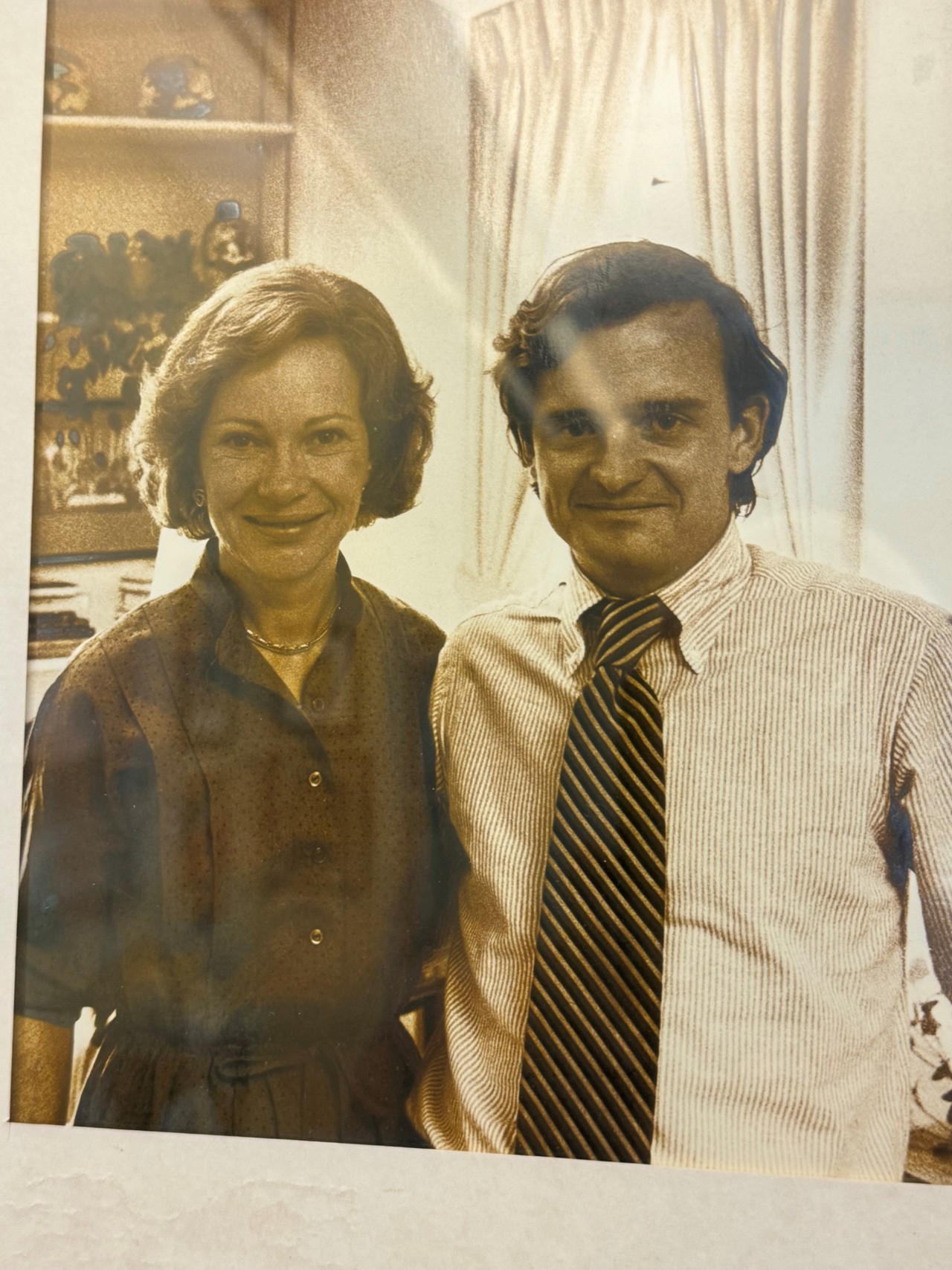

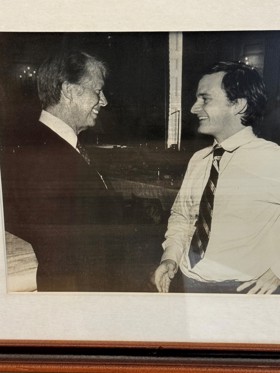

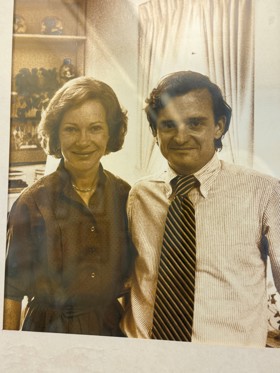

Born in Macon, Georgia in 1949, Stan Jones attended Harvard before going to Oxford to read for a second undergraduate degree in history and economics. After Oxford, he returned to the US and to law school at the University of Georgia. Right after college, Jones worked for then Georgia Governor Jimmy Carter and he went on to serve in the White House under the Carter administration and at the Office of Management and Budget. His legal practice at Nelson Mullins has focused on crafting and managing legislative proposals with a particular focus on hospital, mental health and child welfare issues. Jones is a powerful advocate for improvement in mental healthcare and has served on many commissions and boards to further mental health support, including the Atlanta, Georgia National Mental Health Association boards. This narrative is excerpted from an interview with the Rhodes Trust on 17 October 2024.

Stanley Jones

Georgia & Balliol 1972

‘I probably was born with a campaign leaflet in my hand’

Atlanta was a pretty lively place to grow up. It was fairly strictly segregated, but it already had some tradition of the black and white communities working together here in local politics (since after World War II and because of the large African American business and academic communities). I grew up in the city proper and went to the city public schools. They were all white at the time, to my chagrin. I was not happy to have only that rather unusual white education, but it was a very good public high school in other ways. I liked English and history the best, and what passed for social studies. I did pretty well and was valedictorian and student body president in high school. I was also heavily involved with the United Nations essay contest in Georgia and nationally, so, I learned a lot about the world.

My parents had both got really interested in the civil rights movement in college, and as a family, we supported a lot of activities where black and white folks interacted in otherwise segregated Atlanta. My dad read Reinhold Niebuhr, which took New Testament theology and propelled it into political action, and that was a lot like Jimmy Carter’s experience, so, when I ended up working for the Carters, it all made sense. My family was deeply involved in Democratic politics, and I think I probably was born with a campaign leaflet in my hand.

There’s a Southern liberal tradition in the faith community that is not well known in the rest of the country, and I’m very proud of that. The South is considerably more complex than people realise.

On applying for the Rhodes Scholarship

When I got to Harvard, I found out just how good my high school education had been. I felt very well prepared, although at that time, of course, as with the Rhodes, I didn’t have to compete against the women to get in! There were five or six of us there with pronounced Southern accents, and we took a little bit of heat for being from the South, but I enjoyed my time there and I was a pretty good student. I studied all the courses on Southern history or on race relations, and there were some terrific lecturers. I got the chance to meet folks whose parents had been communists or socialists in the 1930s, and that was something you didn’t see in the South. I also ran the catering business that was part of an effort to create employment opportunities for kids on scholarships, which was fun. We shipped out bartenders in Harvard-red vests all over Boston!

I stayed pretty heavily involved in things at home, around politics and in other areas too. I got a chance to work in a public hospital for a couple of summers, and that intensified my interest in healthcare as an issue, and a right. After Harvard, I got introduced to John Moore (Florida & Balliol 1951), who had been asked to manage an investigation of the large state asylum in Georgia in the 1950s. When Jimmy Carter became governor, Mrs Carter invited John Moore to chair her mental health commission, and he asked me to staff it. He was also heavily involved in the Rhodes selection process and he was the one who encouraged me to apply. He recused himself from the committee and wrote me a letter of recommendation. I had been generally interested in the idea of the Rhodes before that, but I needed the boost from him to get through the nomination process at Harvard. I’m deeply indebted to him.

‘We were in Oxford the year that Watergate was exploding’

I sailed over to England with my Rhodes classmates from the US and Canada, and that was a new thing for me. I didn’t know what to do with five days on a boat, but it was a nice way to get introduced to everyone. When we got to Oxford, I was very pleasantly surprised to benefit from the tutorial method of teaching. We did a lot of writing, and I ended up finding that very stimulating. I did find the economics hard, because I hadn’t done math in seven years, but I was lucky to have one friend who was doing philosophy, politics and economics and another who was doing a DPhil in economics, so, I learned a lot from them and the tutors.

I had a really close friendship group at Balliol, mostly of Americans. We were in Oxford the year that Watergate was exploding, so we would rush to the common room and grab the International Herald Tribune to see what had happened the day before. I think that focused interest made our experience a little less English, and it’s also true that Balliol put most of the international students in the one accommodation block that had good heating! ( No hot bottles were necessary to warm the beds!) I think my only regret is that I didn’t spend as much time with folks from the rest of the world, although during the vacations, we did do a huge amount of travelling. I spent the summer of 1973 wandering around Europe on a Eurail pass, and that love of travel has stayed with me.

‘Mental health as a policy issue became my passion’

After Oxford, I went to law school at the University of Georgia. I was still very involved in politics, and a group of us went to campaign for Carter in the 1976 presidential primaries. When Carter was elected, I ended up working in Washington again on Mrs Carter’s mental health commission, and I worked also at the Office of Planning and Budget. Our team created the Department of Education after President Carter promised that he would take it out of Health, Education and Welfare, and it was one of the administration’s crowning achievements.

I made very good friends around Washington and there were quite a few Rhodes folks in town, but I always knew that I would be coming back to Georgia. For better or worse, wherever I was, I always had one foot in Atlanta. I was gradually able to find my way into the health industry as a lawyer, and as I grew older, mental health as a policy issue became my passion. I’ve chaired a couple of other mental health commissions in Georgia later in my life and I’ve stayed involved in a lot of different volunteer-type activities with the Mental Health Association, including the development of a large housing program for people who suffer from mental illness who are homeless. My heart has always gone out to folks whose minds were a little bit more mixed up than mine and to folks that are having a harder time than I have had, and that’s a personal interest that certainly got intensified when we lost our son to drugs and mental illness.

In my law practice, I gradually acquired clients who were in the mental health space, and I came to really like working at the state level, because things happen faster there. It took 45 years to go from Medicare and Medicaid in the early 1960s to the Affordable Care Act. At state level, you can get something meaningful done in two to three years. For example, I helped a commission in the mid-1990s that created the community mental health centres here and set them up as local public entities. I’ve seen the provision of mental health services change so much over the time I’ve worked in this area, and one of the few upsides of the pandemic has been that it destigmatised mental health issues and brought them much more out into the open.

‘Take your own introspection and join it with other people doing the same thing’

I would counsel today’s Rhodes Scholars to be introspective enough to think really hard about what stimulates them the most, emotionally and intellectually. I think it will be harder to have the types of recognitions that the most famous Scholars get, because the world is bigger and more complicated, and achievements are more extensive. Figuring out your place in the more service-oriented or political roles may be difficult. I think wanting to make a difference is imbued in all of us, and finding out how to do that may take more introspection. That’s one of the nice things that the Rhodes Trust has been trying to do with Scholars in Residence, and I think that makes people fuller. When you take your own introspection and join it with other people doing the same thing, you learn more about yourself and other people and ways to find satisfaction in your work and your family life.

Read Full Interview Transcript

Interviewee: Stan Jones (Georgia & Balliol 1972) [hereafter ‘SJ’]

Moderator: Jamie Byron Geller [hereafter ‘JBG’]

Date of interview: 17 October 2024

[file begins 00:03]

JBG: This is Jamie Byron Geller on behalf of the Rhodes Trust, and I am here on Zoom with Stan Jones (Georgia & Balliol 1972) to record Stan’s oral history interview. Today’s date is 17 October 2024, and Stan’s interview will help us to launch the first ever comprehensive Rhodes Scholar oral history project. So, thank you so much, Stan, for joining us in this project.

SJ: Happily.

JBG: Before we begin, would you mind saying your full name for the recording, please?

SJ: Sure. Stanley Seburn Jones Jr.

JBG: And Stan, do I have your permission to record audio and video of this interview?

SJ: Yes, as long as you destroy it if I don’t like it!

JBG: Absolutely! Well, Stan, we’re having this conversation on Zoom, but where are you joining from today?

SJ: I’m speaking from our house in Atlanta, Georgia.

JBG: How long has Atlanta been home for you?

SJ: I’m 75, so, except for about eleven years, I’ve lived here. So, you know, my two years at Oxford, four at Harvard, three in Athens, and two in Washington were the time I was away from Atlanta.

JBG: Wow. So, were you born in Atlanta?

SJ: Well, I was actually born in Macon, Georgia, because my mother went home to give birth, and rather than her mother coming to Atlanta, she went to Macon, Georgia. That’s where I was born.

JBG: Okay. And when were you born?

SJ: 1949.

JBG: And what was your childhood like, growing up in Atlanta?

SJ: Well, Atlanta was a pretty lively place. We lived in a northern city suburb, north of Buckhead. Atlanta was fairly strictly segregated, but already had some tradition of the black and white communities working together here in local politics. In, I think it was 1963, the population sign downtown flipped over to one million, and, of course, now there are six and a half million people in Metro Atlanta.

JBG: Wow.

SJ: So, quite some change in that period. Atlanta spreads out about 100 miles now. But I grew up in the city proper and went to the city public schools.

JBG: Great. And do you have any siblings?

SJ: I have one brother who is two years younger, Willis Jones.

JBG: And you mentioned you went to the Atlanta public schools. I would love to know a little bit about what your earliest educational experiences were like, in elementary and then high school.

SJ: So, I pretty distinctly remember the third and fourth grade. I don’t have a lot of information prior to that stuck in my head. In the northern part of the city, there were some very good public schools, although they were all white at the time. And so, I went to elementary school for a couple of years and then went to a magnet school in the seventh grade that combined five or six elementary schools and then reshuffled us to three of the better high schools in the city.

This was before desegregation, so, my own schools were all white, to my chagrin, really, and it was about 1976 or 1977 when Atlanta started desegregating the faculty, instead of bussing students here, the faculty shifted among different places. I guess we had a combination of both. But it was a rather unusual, white education. Not so happy about that. But it was a very good public high school.

When I went to Harvard, there was a story – I think it was US News & World Report –or maybe LIFE magazine about the ten best high schools in the country, which were in the places you’d expect – Boston, Chicago, New Jersey, California. And I discovered in college that my own training had been as good as the folks who went to the recognised high schools around the country. So, a lot of that started with a very good magnet school in the seventh grade. We were doing tenth and eleventh grade grammar at age 13, and that stood me in good stead for a long time. We did a lot of writing, fairly advanced math. So, it made high school a little bit easier for me, because of a good kick-off, really, when I was 13.

JBG: And were there particular academic subjects that you gravitated towards?

SJ: Well, I liked English and history the best, and what passed for social studies. I did pretty well. I was valedictorian and student body president in high school, and in lots of other activities: heavily involved with the United Nations essay contest, in Georgia and nationally, so I learned a lot about the world. A lot of that came from my parents, who were both Southern, one from Macon, Georgia, one from Scottsboro, Alabama, but they got really interested in the civil rights movement in college, and we supported a lot of activities where black and white folks interacted in otherwise segregated Atlanta.

So, these things exposed me to a wider view than I experienced at high school per se. I’m proud of that. A lot of it came from my parents’ interest in theology. I guess my dad read Reinhold Niebuhr, which took New Testament theology and propelled it into action, political action. That’s a lot like Jimmy Carter’s own experience himself, so, when I ended up working for the Carters, it all made a little bit of sense.

There’s a Southern liberal tradition, in the faith community, that is not well known in the rest of the country, but it was heavily manifested, obviously, in the post-presidency of Jimmy and Rosalynn Carter. So, yes, I’m very proud of that. The South is a little bit different, a little bit more complex than people realise. There were five or six of us at Harvard who had pronounced Southern accents. I like to say I had some alien influences in Cambridge and Oxford to my own accent, but a few people preserved theirs and it was a point of honour. But we took a little bit of heat for being from the South, without folks realising that it was a much more mixed universe down here than people think of.

JBG: Yes. You shared a little bit about this, Stan, but I’m curious about outside of your academics, growing up, if there were particular hobbies or sports or other kind of extracurricular activities that filled your time.

SJ: Well, I did do some sports. We were at school all day, from seven-thirty until six, and I did track and field. I was the long-jumper and did well at that, because we got to the do the twist at the last ten minutes of ballroom dancing class in seventh grade. But, you know, we were competing only in the white community at the time. (I like to laugh that I won the long jump contest in the 8th grade, but it was the white long jump!) I was the manager for the basketball and the football teams. I was smaller and not a super athlete, but I was in pretty good shape. You used to have gym class every day; that really was much more oriented to exercise than it is in the modern era. I was involved in several civic clubs as well.

JBG: And did you have a sense, growing up, of what direction you thought your career might take, or what you wanted to do when you grew up?

SJ: I think the answer to that is, sort of. So, my family was deeply involved in Democratic politics in Georgia. I probably was born with a campaign leaflet in my hand. And so, we were always going to one meeting or another, promoting the progressive candidates in the local and state elections, and my parents were interested themselves. My mother ended up being quite a good political organiser.

So, as I grew older, I was alert to politics and public policy and, for a long time, I thought I would go into politics myself, and that gradually fell by the wayside as I got more interested in trying to change policies, particularly in health and mental health, rather than just being the front person. I had seen, too, some of the difficulties that the children of politicians had, and so, as I grew older, I think I needed more [10:00] of a personal life, and my ego wasn’t quite the same as a politician’s. I got to the point where I was combining an interest in politics and an interest in writing, and I got teased a lot. One of my friends called me, at one point, a poet and a politician. And so, I think that was true. But when I got back home to Atlanta after working for the Carters in Washington, I didn’t really take the steps that were necessary to get into a political campaign type of life, and at some point, I decided I didn’t want to.

JBG: Yes. I would love to talk in more detail about your experience working with the Carter family, but stepping back a little bit, but I would love to talk about your time at Harvard first, and I’m curious if you went right from high school to Harvard.

SJ: Yes, I did, and started in 1967. That was the time when you didn’t have to compete against the women to get in, so, that was a very lucky break in my life. I was a pretty good student. I really enjoyed the academic part. That was a time when you had a lot of lectures and fewer small-group experiences. I studied all the courses on Southern history or on race relations, and there were some terrific speakers, who taught these (and other) courses. And then, you would have small group seminars to supplement that. But I wanted to be a good student, and that took a lot of time, needless to say. I stayed pretty heavily involved in things at home, around politics and other pieces. I got a chance to work for a public hospital here a couple of summers. That intensified my interest in healthcare as an issue. So, at school itself, I ran one of the businesses that were part of the effort to create employment opportunities for kids on scholarships. I ran the catering business, which was fun. We shipped out bartenders in Harvard-red vests all over Boston.

JBG: Really?

SJ: You know, it was an interesting thing to manage, and I enjoyed that a lot. I didn’t get much involved in the traditional things around school, like the newspaper, the Crimson, or Hasty Pudding and things like that which were more famous in the Harvard tradition. But I had roommates who also went to public school. We sat around and talked in the dining room at our house two or three hours a day, and it was a really stimulating experience. Harvard wasn’t always easy. I think some of the Southerners were viewed as different than we really were. I would hang out with some of the other guys like that, but I also learned, really, from a seminar when we were freshmen, that was about administering social change. It was about the war on poverty at the time. And so, in that group, I met folks whose parents were communists and socialists in the 1930s. That’s something you don’t see in the South. It was new for me. I loved meeting people from all over the country. I had started moving around Washington and New York in high school, and so, the exposure to the country was something I was really fascinated by and enjoyed. So, I think that all formed how I think about things. And I was in the house, the dormitory, where the politicianswent. There were lots of us. It was fun.

JBG: And you shared about some of the work you did during your summers, in a hospital. Was that back in Georgia?

SJ: Yes, in Atlanta. There’s a big public hospital here, called Grady. I worked in a family planning training program that an epidemic intelligence officer for the Centers for Disease Control set up. We learned lots about population, about sexuality. We put on doctor lab coats and went around town handing out contraceptives, which was probably extremely inappropriate, but I got heavily interested in healthcare at that time. I shadowed the administrator of the hospital. I got exposed to the full city, in a way that I had not in high school, in particular. And so, my interest in healthcare really emanates from that particular experience. It was interesting and fun.

JBG: And where did your journey bring you after Harvard, because I know the Rhodes experience came a little bit later, is that right?

SJ: It did. It came a year later.

JBG: Yes. So, would you mind sharing about that year in between, about the work that you did then?

SJ: Yes. So, that’s when I got introduced both to the former Rhodes, John Moore (Florida & Balliol 1951), and to the mental health issues. I lucked into a job staffing a mental health commission for Rosalynn Carter that a man named John Moore chaired. John had a distinguished history in the mental health movement here in Georgia himself. He had been asked to manage an investigation of our large state asylum in the late 1950s. He was the lawyer for the medical association. The doctors at the state asylum were performing lobotomies on patients illegally, and John got called in to investigate that, and so, he became a leader of the mental health movement in Georgia as a consequence of that work.

And so, when Mrs Carter became governor with Jimmy, she invited John to chair her mental health commission, and he invited me to staff it when another person in the law firm got drafted and joined the reserves. So, I lucked into that job, though he and I hit it off. He was heavily involved in the Rhodes selection process and encouraged me to apply. He recused himself from the committee and wrote a letter of recommendation. So, I’m deeply indebted to him for the opportunity to get to Oxford. You know, I had been generally interested before that, but I needed the boost from him to get through the nomination process at Harvard.

JBG: He was a Scholar himself as well?

SJ: Yes, he was. He was from Florida, also went to Balliol. I think he was probably class of 1954, or maybe 1951. And we kept up for a long time. I mean, he went to Washington, also with the Carter administration, and ran the Export-Import Bank for a while and eventually ended up working in Tokyo for Bechtel. So, we drifted further apart physically over time but my indebtedness to him is significant, and he’s the one who taught me about mental health as an interesting policy issue That became my passion as I grew older, and I’ve stayed involved in a lot of different volunteer-type activities with the Mental Health Association and in the development of a large housing project for people who suffer from mental illness are homeless, that Mrs Carter also chaired. I ended up working in Washington on her national mental health commission and then have chaired a couple of other mental health commissions in Georgia later in my career and life. It’s been my passion.

So, you know, I think my heart always went to out to folks whose minds were a little bit more mixed up than mine was. I was lucky to have good genes to start with, and as I watch folks struggle with less genetic inheritance, if you will, my heart goes out for them. And I think, it’s partly because I was a good student, and I identified with being a good student, and so, folks that are having a harder time, I feel very empathetic towards and sympathetic to. And so, that’s how I got started and, it just grew over time. It’s, like, I found a niche, really, for my interest in politics and policy, and that became it, and some of my law practice, also, was around hospital issues that were heavily involved in policy issues at the state legislature. So, over time, from when I came back home in 1979 and joined a law firm, pretty soon after that, I was heavily involved in health issues at the state legislature, and that grew over time. I liked it a lot. I had liked it when I worked for the Carters in 1971 and 1972, before I went to Oxford, and it was just fine. [20:00] So, you know, it’s, kind of, entertaining: I got dubbed ‘Mr Mental Health’ at the state Capitol after 30 years of this, and so, it’s a personal passion, a personal interest. It got intensified when we lost our son to drugs and mental illness. All of a sudden, some of this made more sense than it had to start with and that just generated more and more interest.

So, over time, I would learn a lot about mental illness. I knew a lot about how it was administered at the state level, gradually acquired clients who were in the mental health space, like hospital clients who had mental health units, the crisis and access line for the mental health system, a national mental health company that was helping manage the state community centres, mental health centres. So over time, more and more of my work gravitated toward the same subject matter, and I’ve enjoyed it a lot. I mean, it’s really interesting. I think I decided fairly early on, probably in late high school that health insurance, national health insurance, national health insurance coverage was important for solving some of the problems of poverty in our society, and I’ve gradually really liked working at the state level, because things happen faster. A pronounced example of that is, the time between the Medicare and Medicaid in the early 1960s and the Affordable Care Act in the 2008 was 45 years. It took a long time for all the interested parties, the professional groups, pharmaceuticals, the hospitals, financing, you know, to coalesce around a way to expand healthcare coverage. Well, at state level, things happen in two to three years and it’s more down-to-earth, it’s a little less pretentious, and it’s pretty well-humoured. I mean, humour, that’s also an important thing to me too.

But I’ve thoroughly enjoyed working at the state level and it just, kind of, fit over time. I don’t know how to say it any better than that. And I got started, really, before I went to Oxford, on some of these things. So, by the time we got there, and there were obviously a lot of people interested in politics, but I had the most direct experience at that point, you know, working for Mrs Carter and Governor Carter when they were at the state level, and then, of course, a lot of us in our groups, in the classes around me, landed working for Carter also in the White House. So the kind of, exposure to a wider group of people at Oxford and through the Rhodes, and Marshall, for that matter, really deepened my scope, I guess is what you would say, and brought me in touch with some folks who were really interested in all these things. Most of us have stayed connected for life. It’s not always constant, but Oxford was powerful experience, even if it’s every five years or so, because you have some pretty dramatic shared experiences, and that’s true both for college, graduate school at Oxford, and the Carter presidential administration.

JBG: Wow. I’m curious, Stan, thinking about that first year working with John Moore and when he was encouraging you to apply for the Scholarship.

SJ: Right.

JBG: Had you thought about studying in the UK before? Had you spent time in the UK? I’m curious about what it was about that idea that resonated with you.

SJ: So, I had thought about it, generally. I knew that folks who were doing well in school and had some roundedness, that was an opportunity that was available. I had missed out on a chance to go to a London student conference in high school because I got sick in New York, before the plane took off. I had studied the United Nations a lot, and there was a UN essay contest that I won four times in Georgia and came in second in nationally one year, and so, my horizon was getting a little bit broader, early in life. But in terms of a specific kind of knowledge of what Oxford would bring to the table, I was only vaguely aware of that, and so, I was very pleasantly surprised to benefit from the tutorial method of teaching. Obviously, we did a lot of writing, and I ended up finding that very stimulating. I think I mentioned they stuck the international students back in a corner of Balliol that had heat. So, those of us there had a different experience than people living in Magdalen or, some of the places that were only old-fashioned. We didn’t have to have water bottles to heat our bed and things like that!

But there were lots of people and we enjoyed each other,. We were there the year that Watergate was exploding, before the Nixon resignation, and so we would all rush to the common room at Balliol and grab the International Herald Tribune and see what happened in America the day before with the investigation of the Nixon break-in at the Democratic National Committee That consumed us a lot. And, of course, Vietnam was still not solved, so to speak. I grew up in era – we all did – where the Vietnamese War was ever-present and the elections of 1972, 1976, in particular, 1968. It was front and centre for a lot of people in public affairs in America, in a way that made our experience a little less English, if you will, because we just got so focused on that. I wish that hadn’t been as true as it turned out. I adored my American friends in the back corner at Balliol. We had a couple of other guys from public schools in St. Louis. They were my best buddies – Bob Haar (California & Balliol 1972) and Gerry Sauer (Missouri & Balliol 1972), and some of the Georgians who were there. Three of us Georgians bought half a pig and dug a barbecue pit and cooked it out on the Cherwell. So, trying to show a little bit of Southern culture to everybody else. It was a lot of fun, and things like that happened all the time.

And, of course, there was a huge amount of travelling in the off-terms. I spent the summer of 1973 wandering around Europe on a Eurail pass. And another one of our Oxford buddies was studying, coal mining and land reclamation in Germany. His name is John Gaventa. He became one of the true-believer, public-service-type people. He works in a non-profit around, mining and climate issues. So, he took us all to Germany and we watched these massive shovels on spinning wheels dig up the earth and dig the coal, and put the dirt back at the back end of the pit. He was just a nice example of someone who had a very clear mission and would teach the rest of us about it. I think that’s one of the strengths, really, of the Scholarship, in my experiences with it. But the travelling was stunning, and my only real regret is I didn’t spend as much time with folks from the rest of the world. I think part of that was because of Balliol’s character at the time. It has a government service tradition from the 1860s or so, and so, people were attracted to it who were interested in these kind of things. It had a lot of international students, and they put us all back in the corner where the place was heated. So, that isolated us a little bit, but it was also charming.

JBG: So, what did you read at Oxford, Stan?

SJ: I read history and economics. It was a combination major, where the two separate faculties put the programming together. You did half economics and half history. There was some distribution of the history courses from the nineteenth century to the modern era. You could do older or newer eras as you chose, and then, you took exams. At the end, you had four exams in each of the subjects. [30:00] The economics were hard for me. I hadn’t had math in seven years when I’d started doing that. So, it probably wasn’t the best decision, but I did learn a lot of macroeconomics, in particular. I couldn’t do the statistics around the micro stuff, butthe group of us back in the corner of Balliol, we had one person who did traditional PPE – Gerry Sauer – Bob Haar did a DPhil in economics, and then several of us were doing these combination majors. History and literature was another one, an example of combining, the English and history faculties. I think those things had started, probably, in the 1950s or 1960s, but they did let you get a different kind of breadth, and if you’re not an academic, it was actually useful to combine subject matters like that. I think if you were more of an academic person you needed to head deep into what your major interest was.

JBG: So, if we could jump back for just a moment, I would love to ask you about the experience of sailing over with your class. Did you sail over with your class?

SJ: We did. That was really delightful. We took the Queen Mary from New York to Southampton. We had a nice combination of Rhodes and Marshalls and folks going to Oxford on their own who could join the trip. It was a new thing for me. I didn’t quite know what to do with myself for five days on a boat, because I was astern, serious kid, you know. So, Jesse Spikes (New Hampshire & University 1972) and I, we sat together at our table. It was pretty entertaining. There was the daughter of another Rhodes who went with the group and she was queen of the ball, if you will, of the ship, and she eventually married one of the other guys from the Southeastern region. But, you know, it was a nice experience. It was tight. It was an era, probably, when the ships didn’t have as many balancing techniques, so, there was a fair amount of sea sickness in the experience, but still, it was a lot of fun. I guess there have been some years recently where that didn’t happen, which is too bad, because it was quite a nice way to get introduced to everyone and to have a different style of experience than I think any of us was used to. So, it was very pleasant.

JBG: And as you were moving through your time in Oxford, were you expecting, at the end of that time, that you would return to Georgia?

SJ: Yes, I always had that in mind. Yes.

JBG: Okay. So, you always expected you’d come back to Georgia.

SJ: Right. For better or worse, I always had one foot wherever I was and another foot in Atlanta. That was part of my interest in politics too, because we were, in a state growing, in the middle of change with both progressive and very conservative strains and traditions. Georgia, came into its own with the Olympics in 1996, and with Carter’s election to president, too, when it demonstrated that the South was a little bit different than you’d thought. Atlanta has always had a large professional African American and business class, and the two communities here in Atlanta talked to each other in the 1950s and 1960s, and became more together over time, so, there was, kind of, a notion of Atlanta as a city where the races could get along better. And that was in pretty stark contrast to places like Birmingham, Alabama. Atlanta won the regional airport because its racial politics were more moderate, and, of course, now, we have the biggest airport in the world. So, lots of things have happened in Atlanta that are interesting. So it’s a more moderate politics: black leadership from the 1960s, the Olympics, Carter’s election and, you know, a burgeoning technology sector. There’s a lot of export out of Georgia to the rest of the world. So, we are a pretty complicated place, with a little bit different patina than the rest of the Southeast. That was always interesting to me. I was very proud of that, proud to be part of it and to call that part of the personal tradition that I got from my family and from living here.

JBG: And so, did you go right from Oxford to law school?

SJ: Yes.

JBG: Okay.

SJ: I came home, and I was better suited for law school after having done the work with the Carters and being at Oxford. I went to Georgia Law School. That was part of my interest in politics at the time, to come back home and try to normalise myself a little bit. The professors knew that I had been to Oxford, so, I got called on three times the first day in law school.

JBG: Wow.

SJ: Kind of, entertaining. I probably have dressed that story up over time a little bit! I got involved in student bar association politics. You know, ten of us went to New Hampshire and campaigned for Carter in the 1976 presidential primaries. So I was viewed as being headed to being a politician, at the time. I enjoyed being there; Athens, Georgia is quite an interesting and warm campus. It both has very traditional-looking places and very new-looking places. Over my lifetime, the university has really risen in its stature around the country. It lost its accreditation in the 1950s, because of some racial interference from the Governor, and then it became more independent. The law school got established as a bastion of integrity, really. And so, I was also pleased and lucky to be part of that.

JBG: So, you were in the middle of law school during that 1976 primary?

SJ: Yes.

JBG: Okay.

SJ: Close to the tail end of the second year.

JBG: So, then, where did your journey bring you after law school?

SJ: So, then I went to Washington and worked again for Mrs Carter on her mental health commission, and I worked also at the Office of Planning and Budget. Our team created the Department of Education.

JBG: Wow.

SJ: Jimmy Carter had promised the National Education Association that he would take the division of Education out of the Health, Education and Welfare department, so that it would have more stature and direct access to the President. The team I worked on after working for the mental health commission created the department, and we analysed 250 education programs across the federal government.

JBG: Wow.

SJ: It was ridiculous how dichotomised everything was, and then we put the things together that made the most sense, and that became the Department of Education.

JBG: Wow.

SJ: And we still have it today, needless to say, and it’s one of the crowning achievements, really, of the Carter years and of his administration.

JBG: Wow.

SJ: I made very good friends there. There were quite a few Rhodes folks around town. Some of the guys were clerking on the Supreme Court, after we’d finished law school, and there were other people doing writing or working in the administration, and we kept up pretty well for that era. That was very fun.

JBG: And how long were in Washington?

SJ: Two years. So, I was starting to get terminal Potomac fever, and I decided to come home and try to be a lawyer for a little while before I lost the opportunity to do that emotionally. So, I left in late 1979. I had worked for Mrs Carter in the White House for five or six months, but I had made up my mind that I needed to get back home and try to learn how to be a lawyer before I got too far away from it, and if you don’t do it fairly quickly, it becomes harder to get started at it later. So, for better or worse, I thought I needed to at least try it out for a while.

JBG: And where did you begin your law career?

SJ: So, I worked for a firm called Long & Aldridge in Atlanta. It was a spinoff from one of the large national firms, Sutherland Asbill & Brennan. It was a very talented group of people. My best friend from high school was there. She recruited me. I did that about 15 years and gradually, was able to find my way into the health industry as a lawyer. So, it was fun to be around the state administrative process that controlled the growth of hospitals and surgery centres, nursing homes, as I had always been interested in healthcare [40:00] generally. So, this subject matter put me in the middle of what was going on in the health industry in the state. So, it was interesting and challenging intellectually, and it was also in the center of health politics. I liked that a lot. I then got started working with the Mental Health Association locally and at that state level and was an officer in that for two or three times over the years. Eventually, I got tired of going to meetings, so, I organised the golf tournament for the Mental Health Association for 25 years and raised about one million dollars.

JBG: Wow.

SJ: So all these things, starting back with working for Rosalynn and John Moore in 1971, built up the mental health activities that I did as a volunteer. Some good, very close personal friends and Mrs Carter started a supportive housing project, called Project Interconnections, in the late 1980s, and it’s grown into the largest provider of supportive housing for people suffering from mental illness in Atlanta. There were other mental health commissions that came along. I helped a commission in the mid 1990s that created the community mental health centres here and set them up as local public entities. That was done to try to build up the community services and get away from just institutional or hospital care, and also to give more local control and input into how that worked. So, the leading developmental disability advocate and I shared the chairmanship of that commission.. She was quite a character, from Southwest Georgia, a bigger than life person. She wore black heels to the Capitol all the time and strutted around, but her heart was really strong, to help folks with intellectual disability, and I was the mental health person, so, we did that together.

JBG: Wow.

SJ: And, all these things just kept reinforcing my interest in mental illness and so, it became my policy passion throughout, all these years and events, and, it’s been a pleasure to be around it. You gradually learn a lot more about mental illnesses. You learn a lot about stigma against seeking help or talking about your mental illness issues. You learn a lot of about just the financing of care, how it interacts with Medicaid, which is in a different system. And so, gradually, over time, I just was lucky enough to learn a lot of about these things, and I enjoyed them. I’m pretty well-humoured, so, it was also fun to be at the Capitol. Georgia has a short legislature. It’s about 40 days and 80 nights, is how people describe it. It’s two-and-a-half months, January to April of every year, and so, it’s very intense. It’s such a mixture of trying to manage people’s political ideology or philosophy and things you want to get accomplished for your clients. How do you pay for those goals? How do you shape what you’re saying to fit the political context?

So, Georgia was heavily Democratic until 2004 and it’s been completely Republican since then, at the state level, not at the presidential level or in US Senate elections We are in another period of transition here. We’ll see what happens next. It’s going to be really interesting in three weeks to see who wins. It’s a dead heat right now. To operate in the political arena difficult. I get branded as a Carter person and a Democrat, and so, some Republicans won’t talk to me for that reason, and in the first part of my career, I enjoyed the opposite, where the Democrats were in charge and you were acceptable in the political establishment. But all of that is interesting and challenging, and stimulating mentally and, really, emotionally, because nothing is easy in this type of mixed-up history that Georgia has.

JBG: Yes. Would you mind sharing a little bit, Stan, about, perhaps, the changes that you’ve seen in the systems, in the mental health system and in the healthcare system, throughout your career?

SJ: Sure. So, I’ve been thinking about that a lot lately, anticipating the interview. Georgia had the biggest asylum in the world. We only had two locations where folks who suffered from mental illness or intellectual or developmental disability or extreme physical disabilities were sent off to Central State Hospital in Milledgeville or a nursing home in Augusta. Milledgeville was 110 years old when John Moore and I got started and had 12,000 people.

JBG: And did you and John Moore work together there? Was that where you worked?

SJ: Yes. He did that first, and I came along ten years later.

JBG: Wow.

SJ: And so, it started decentralising then, but Georgia was very slow to develop a community based mental health system, which was the rage, if you will, in public policy from the Kennedy administration forward. There was a conscious effort nationally to push states or help states build up their community based systems so that people were not isolated into a state asylum. And so, that has gradually happened here. In the mid 1990s, early 1990s, the mental health commission was about creating local public mental health agencies that were set up in every part of the state, and the expectation was that you would manage both inpatient and outpatient services, some prevention services in the schools at the local level, not at the state level, and it was conjoined with trying to reduce the stigma of mental illness by moving away from isolating people who suffered from it into a central hospital and letting them be in recovery in their communities. Georgia was also front and centre on the recovery movement, where we started training and employing former mental health patients to be peer supports in the community based mental health system, and we were the first state to get the Medicaid system pay for peer supports.

And so, today, a good programme has a psychiatrist for medicine, psychologists, social workers and counsellors for the counselling sessions and then peer supports who are helping people learn how to be in recovery and live in their communities. So, destigmatising mental illness has followed from doing all these several things. In the recent ten years or so, both the states and the federal government have built up what are called crisis services. So, that includes, a call-in line, a phone center. Now we have it nationally in the 988 call-in system. The current work also includes putting mental health services in the school system. Mrs Carter was really involved in that, in her annual mental health symposium. Now, the mental health system puts a counsellor in every school, and so, that was every helpful, because most school counsellors were focused on academic and career functions more than they focused on services for the kids who were having the hardest time. It is actually the school social workers who do the most help to the kids who don’t have enough to eat or who are struggling emotionally. And then, after the mental health system put counsellors in the school system, you had several people in every school who were attending to all the issues that a kid and a family really faced. So, all these things I’m talking about, the peer supports, the development of good crisis centers, the development of a call line, putting more services in the school system that encounter the kids at the youngest ages with issues, those have been dramatic changes. Georgia has actually led on those things, even though it was the worst state with the biggest asylum, when John Moore and I got started on this.

JBG: Wow. That’s amazing. And you have now been at Nelson Mullins for 30 years, is that right?

SJ: Yes. So, my first firm wasn’t much interested in healthcare, so, I gravitated to Nelson Mullins. It is a large national firm based in South Carolina, and they had several people already doing healthcare services. Healthcare wasn’t really a legal specialty until the late 1980s, mid-1990s. So, Nelson was a better home for [50:00] me, for the things I was doing as a lawyer and for some of my volunteer interests too. It’s always been very supportive of pro bono activities. It’s allowed public policy advocacy to count as a pro bono activity, rather than just legal services to people who couldn’t afford them. And actually, I got a lifetime pro bono achievement award from year ago, which surprised me, but it’s very pleasant to be recognised in that manner. We also passed a state mental health parity act in Georgia, in 2022. So, that’s the effort to make sure that insurance and Medicaid, Medicare, pay as much for mental illness as they do for physical illness, and they don’t discriminate against mental illness by paying for them less or approving mental health less. The Federal Parity Act is something that Mrs Carter had worked on for years and it happened in 2010, I think. We came back with the state act in 2022, and I was in the thick of that and enjoyed it, and I actually got ‘lobbyist of the year’ from my peers the following year.

JBG: Wow.

SJ: I didn’t expect that, but it’s a nice culmination of recognition for mental illness as being important. And, of course. Covid destigmatised mental illness altogether. The isolation pushed up the suicide rates for kids and, in Georgia, for farmers. So, in our rural politics all of a sudden it was acceptable to talk about mental illness, because it was affecting people that no one expected to have issues, the farmers in particular and, of course, the kids have always had growing issues over time, as life gets more complicated, society got more harsh, if you will. And so. I really think that Covid was a great event in making us more aware of these things. ‘Great’ is probably not the right word to use, because of the suffering that resulted from the pandemic, but, in mental illness in particular, it really lifted it up as a subject matter we all need to be concerned about, and I don’t think we will ever suffer again from as much stigmatisation around mental illness or developmental disability as we have prior to Covid. It’s really normalised the discussion, and it’s finally got to the point where about a fourth of the population has an issue in their family or themselves every year, and so, now, we’re able to talk about that a lot more, and, that’s a big breakthrough in dealing with things that are pretty important.

And we also know now, much better than we’ve ever known before, that taking care of mental illness helps reduce your physical illnesses, or detecting your mental, your emotional issues in the physical health system helps you get more help in that realm as well. So the two are combining now in a way they haven’t done before. And the parity act, of course, is trying to address that more directly from a health insurance payment point of view. But I’ve really enjoyed, and been lucky in my life, being in the thick of this at the state level where things happen faster. That’s my pitch for working at the state level, if nothing else. And, of course, national politics are more complicated now than they’ve ever been, and more intransigent, so, that’s also another good reason to play at the state level. You know, states are becoming experiments for new ideas now, and that’s true in conservative and progressive states. But the fact that things happen here, that they’re a little more accessible, a little less partisan, perhaps a little less ideological makes working at the state level more interesting and more hopeful, really.

JBG: And Stan, I believe you touched on this a little bit earlier in our conversation, around some of the work that you’ve done at the intersection of housing and mental health, and I was wondering if you would mind sharing more about that.

SJ: Sure. So, that’s a hot topic now, but I got started on that with Mrs Carter, again. She was my mentor in life, with John, and we set up a nonprofit that developed housing for homeless, mentally ill people in the late 1980s, and it’s the biggest provider of residential services for folks suffering from mental illness. And, of course, if somebody’s life is falling apart, because of their bipolar disorder or schizophrenia, they need a place to live. They need a place to recover and be part of the community. So, trying to build up supportive housing is part of the community mental health movement to enable people to live around other people and not be isolated, have access to their families, and so, that’s how the housing and mental illness subject matters can converge, if you will, that we just need more places for people to live safely. And, as housing prices have risen, particularly in the last five to eight years, housing has become more of an issue for folks who weren’t making as much money than they had been earlier. So, we don’t really have enough housing stock in affordable housing, in almost all of our cities in the country, and because that’s true, as rents go up, that’s one thing that causes more people to live on the street, whether they’re in tents or cars.

And so, I think what started as a supportive housing movement -- ‘supportive’ meaning services with a place to live for people suffering from disabilities, mental or intellectual, gravitated into, ‘We also need more places for people to live who don’t make as much money.’ And, it’s central to one part of our American dream that you have your own home. Well, that’s not possible, in the current economic situation with high interest rates. And so, all of these factors together have propelled even conservative governors towards developing more affordable housing and developing more supportive housing. That’s very interesting. In Georgia, we have a fairly conservative governor. He’s a very warm person, but he’s a Reaganite – you know, ‘Government should be smaller’ – and so, the interest in spending public dollars on things like housing is a little foreign to some folks who are on the more conservative side of the political spectrum.

But Georgia has been growing. We’re now 11 million people. We’re going to pass Ohio and probably Pennsylvania fairly soon and be the fifth or sixth or seventh largest state after the 2030 census. And so, as you grow like that, you don’t have enough places where people cam afford to live, and as you recruit business, to try to build jobs for your citizens, you also have to have a place for the incoming people to live, and so, housing has become an acceptable target or policy goal for even conservative governors. We’re in the thick of that here now. So, the governor put up a fair amount of money for developing housing around two rural car plants, electric car plants that Georgia has recruited. So, you can take economic development, which is more of a conservative politician’s goal, and it doesn’t work unless you have a school system, a health system and a place to live for the people that you’re bringing in. This is particularly true when housing being more expensive.

Our young people need places they want to live and can afford. All of these things are making housing more acceptable as a political issue, and there are things that governments can do to help that. So, the current proposal to subsidise your first home purchase is the most recent example of that. The state paying for infrastructure – sewers, streets and curbs – is a normal version of that over time. And so, I mean, in every state and certainly every city, where these issues are more pronounced, all of a sudden, housing has become a hot topic, if you will an acceptable topic to both parties.

So, that’s very interesting, and we have several clients in the thick of that. We’re involved in it as volunteers too, on some of our pro bono projects. But we help the homeless provider financier in Atlanta, for example. We help the mental health crisis and access line. We help some of the adolescent mental health programs. And those kids, as they age up, and just get into the workforce, if they’re lucky, they also need places to live. So, all of this [1:00:00] moves in the same direction, and I think that’s true nationally right now, and it’s going to be interesting, because, in some ways, it becomes a philosophical disagreement between the parties about whether it should be only private sector, which it historically has been, by and large, or is it a policy that the government needs to support, so that you’ve got both public and private sectors creating investment in housing and industry. That’s one of the more interesting things around the party political debate, this year, and for several years in the past and going forward.

JBG: So interesting. I’m curious, Stan. So, as you have an incredible both professional career and the pro bono and volunteer work that you’ve done behind you, and that you’re in the midst of at the moment, I was wondering if you would mind reflecting a bit on what you would say motivates or inspires you today, at this stage in your life.

SJ: Well, good humor is probably one of the main inspiring things, and that something is both interesting and fun. It’s mentally, intellectually satisfying that the interest in the things that have been important to me have become more prominent in the recent era, because of Covid. Destigmatising mental illness is probably the most pronounced example of acceptability to be interested in these things. I have enjoyed getting a little bit older. You know you have a longer-term perspective on what you’ve done in your life, what’s been important, and what’s most important. I don’t know if I’ve done this well, but I’ve tried to live honoring both my emotions and my career and achievement. So, I sometimes feel a little guilty that I didn’t land in the politics more deeply, but I’ve found a way to participate in it and enjoy strong family engagements, and try to be supportive of all the people around me, to recognise thecoming into their own of women in the late twentieth, early twenty-first century.

That’s been emotionally important to me. It was front and centre in college. It’s embarrassing that I have benefited from not having to compete against women, in many things that have happened. But I love that culture has become a little more even, and that opportunities have opened up in for both sexes and for multiple ethnicities in our country. So, those things feel good and satisfying towards the end of my life. ‘Inspiring’ is not quite the right word, but it’s satisfying to feel like you’re trying to be part of all that, and that probably keeps me going as much as anything. I probably, as an adult, have more women friends than men, and I can myself a feminist Democrat, if you will, which I think is one category on the progressive side of the political spectrum.

And so, I’ve enjoyed watching and thinking about and participating in a lot of these social changes that have been dramatic. Going forward, it’s going to be interesting to see how all this plays through. We’re obviously global. Some parts of our political culture retreat from that. They don’t find that interesting. But, it’s just an inevitable part of life, if you will, going forward. There have been huge benefits from it, and huge difficulties. And I think for future Scholars, trying to figure out how to participate in a world that’s more international, and is bigger because of that -- that’s an interesting challenge, and a tough one. So, I hope folks learn more languages. I hope they can think more carefully about how to merge whatever their interests and ambitions are with their private lives.

I think that’s a challenge, and because I was interested in politics, I knew a lot of people that didn’t do that very well but succeeded in the political world, and I just-, I guess, because of my interest in mental illness or mental health, if you will, I know that satisfying both parts of your life or, however many you want to describe, but the personal and the career and trying to merge them and support the people around you, that’s important. And you get a lot of attention when you’re young and you’re used to being the centre of it-- that’s not the best way to live sometimes -- I think it takes a while to learn how to do some of those things better. I think it takes a real deep knowledge of what it is that interests you the most, that is stimulating mentally and emotionally, and, you know, I like the way that the Trust has gotten more involved in connecting to people. When we were at Oxford, you were left to your own devices. You could go ask someone for help, but there weren’t these conferences and seminars that you all are organising now. Its’s it’s central for the Warden and has been for her predecessors. I think the experience sounds much richer now than it used to be, and more intentional about connecting people and their interests, and talking about what they like to do. I think those are all very good things, and I wish I’d had the chance to participate in them a little bit more.

JBG: You mentioned, Stan, your family, in the context of the way that you were thinking about career options and thinking about how that intersects with family life, but I was wondering if you’d like to share any more about your family.

SJ: I’d love to do that. So, my wife, Barbara Cleveland – she goes by ‘Bobbi’ – and I have very common interests around child welfare and mental illness. She ran a foundation here for 35 years. I was really lucky enough to get attached to that. I could tag along and learn what the donor community was interested. She’s a very tough-minded, policy planner. So, she would pick out things that were really interesting and oriented to social change, whether it was in health or mental health or education, and she supported a lot of pilot projects around some of these things that we both care about a lot. So, we’ve had a nice merger of emotional and mental interests, if you will, to do some of these things together. Her foundation funded the first couple of hundred thousand dollars for the housing project that Mrs Carter started in the late 1980s. I was chairman of that for a while.

JBG: Wow.

SJ: We have a blended family. The three kids get along pretty well. They have different gifts live with us. My son Mike and his family live about 20 minutes away. And we have another son and his family: they live in Africa, working for the Centers for Disease Control. When we got married, Bobbi’s older daughter, kind of, adopted my older son. The two younger boys shared a room and liked each other, and they were different but they appreciated each other.

So, this has been immensely rewarding and interesting, to watch these things blend and evolve. You just feel part of the divorce demographic in American culture. But it’s worked out pretty well for us. And we both love Montana, which is a family legacy for my wife. Her dad was from Montana. Her favorite aunt had a house in Glacier National Park. We spent many summers or parts of summers there, and like the rugged hiking and walking. That’s enriched both our lives. I feel lucky to have gotten to be part of that. We do travel a fair amount. Life feels pretty rich. I think we’re both hoping to have a few more years where we can wander around the world a little bit, and I wouldn’t have been interested in that, you know, but for going to Oxford, really. I love Asia. I bought a Pan Am Round-the-world-in-80 days ticket when I finished working in Washington. That was a treat.

JBG: Wow.

SJ: You could go on Pan Am I or Pan Am II. You had to go in the same direction and then, you got to really see the rest of the world, and particularly Asia for me, then. I was mostly doing European stuff in Oxford, of course.

JBG: Wow. That’s amazing.

SJ: So, you know, we’re part of a pretty active school community. We did it for our own kids and now we’re doing it for our grandkids. That’s a lot of fun. So, towards the end of your life, you can appreciate the richness of the things you’ve been lucky enough to do, and you learn a little bit from each one of them. That’s precious to me.

JBG: Lovely. Well, Stan, as we enter the final segment of our conversation, I would love to ask you a few questions about the Scholarship, the first being, what impact would you say that the Rhodes Scholarship had on your life?

SJ: Well, it’s an automatic credential that opens a lot of doors, gives you entrée to opportunities, if you will. I live in a more conservative state and I’m a little cautious about it, so, I don’t want to seem pretentious by calling attention to it, but, people will talk about it a little. They think you’re smart, whether you are or not. I mean, that’s, sort of, a plus. I don’t know. In a way, I would say it’s the opening of your horizon that comes from being abroad and doing a lot of travelling. That, probably, is the best gift to me. You know, it’s interesting, the members of our classes there, we don’t hang out a lot together, at least, I don’t, but there’s almost an intimate, kind of, bond that comes from having had the experience.

So, you have a knowledge that you can always call up somebody and you can enjoy sharing the things you’ve done. You, sort of, enjoy bragging to each other about what you’re up to. It’s a mental and emotional bond, I think. In some parts of the country, you have to enjoy it a little more privately! That’s true down here. But you also feel like you get a chance to touch the rest of the world, is one way I would say it, and I wouldn’t trade anything for that. I think we need to all have broad horizons as the world gets smaller, at least in terms of communication and technology. Bigger awareness of what’s going on in places that are different helps you at least try to promote a less isolationist, more forgiving view of the rest of the world. So, all those things feel like the legacies for me. I like the fact that the Scholarship has become much more diverse. That’s true ethnically, and gender-wise. That is refreshing. Those are the things that I think that I’ve been thinking about the last few days, when I knew you would ask me that question.

JBG: Well, thank you. And you have touched on this a little bit, speaking about the direction of the Scholarships, but we’ve just celebrated the 120th anniversary of the Scholarships, so, a great opportunity to reflect on the history of the Scholarships, which is one of our hopes for the oral history project, but also a great opportunity to look ahead to the next chapter of the Rhodes Scholarship, and I’d be curious to know what your hopes for the future of the Rhodes Scholarship would be.

SJ: Well, I like the diversification and the support for other programs, both by example and by financing. Opening it up to additional countries is appealing, to my way of thinking. Now, I guess we’ll have to deal with China in a way that we maybe haven’t gotten around to, exactly. Because we still have an origin in the English-speaking world, I suppose those are the natural places to expand. It probably has to get bigger, because it’s a smaller group annually, and, as we open it up more, it’s harder for people to get the benefit unless it does expand in size. That will mean more private fundraising. You know there has been some success recently, and certainly, when you think about what people have done, there’s opportunity for improved fundraising, just from the base. Sometimes, I’ve seen other leadership development programmes, if you will, you know, that just spin off similar activities in other places.

For example, here in Atlanta, there’s a leadership seminar – it’s called Leadership Atlanta – and now it’s in six counties around here. And so, as places get more populous, it allows you to build a common bond, among the leaders in a particular area. Perhaps an idea like that is-, expensive and hard to implement perhaps, but that would be something to think about: how do you take the notion of leadership development and replicate it in other places? I haven’t heard, the Warden talk about that a lot lately. She did last year when she was here, a little bit, and I know it’s on her mind, and part of her life at Agnes Scott College in Atlanta. So, those are the kinds of things I think about. It would be fun to be involved in that discussion a little bit more. I mean, sometimes you’ve got to know enough about what’s actually happening, to be a good creative thinker about it, and most of us are probably are a little too remote from that, but it might be worth a seminar topic, that’s conducted Zoom-wise.

(Maybe that’s already happened and I don’t know it.) I’m trying to think of ways that you, can engage the conversation, get people talking about it and thinking about it. Eventually, you have to move towards more government support, and that’s probably not an easy topic, given the philanthropic origin of the Scholarship itself, but if you’re going to spread out the benefits a little wider, you’ve got to have a way to pay for that. I’d be interested to see whether that’s anathema, to say something like that in the discussion. I haven’t been close enough in to know how that’s been talked about.

JBG: Thank you, Stan. My final question would be if you have any advice or words of wisdom that you would offer to today’s Rhodes Scholars.

SJ: I was trying to think about that this morning and touched on it a little bit earlier. As the world gets more integrated and complex, the urge towards more specialization will be a natural consequence of that. So, I would counsel people to be introspective enough to think really hard about what stimulates them the most, emotionally and intellectually. I think it will be harder to have the types of recognitions that the most famous Scholars get, because the world is bigger and more complicated, and achievements are more expensive.

Understanding yourself emotionally and intellectually seems like a key starting place for that. So, I think some [1:20:00] of the traditional roles in academics and politics will continue, but the things that are more service-oriented than those, may be more difficult to figure out. You know, how you make a difference, which is imbued in all of us, to want to try to do that. Obviously, you’ll probably need to be more multidisciplinary going forward, not just in use of technology, but also understanding integration of ideas and subject matters. I think some of that is happening in universities around the world already. If you look at a public university and just look at the description of the subject matters, they’re very non-traditional and they’re very work-oriented.

So, that’s important. It’s important for making sure that all of our population can be employed and find stimulus, satisfaction from work, as well as family and your love life. I mean, all those things are going to become harder to integrate, I think. So, it takes more introspection, and you can do that better when you’re talking to other people more, and that’s one of the nice things that I’ve understood that the Trust has been trying to do with Scholars in Residence. I think that makes people fuller, if you will. And so, you take your own introspection and join it with other people doing the same thing, and you learn more about yourself and other people and ways to find satisfaction in your work and your family life.

JBG: Great. Well, Stan, we are so grateful for your participation in the oral history project and helping us to launch this initiative, and I would love to invite if there is anything else that you’d like to share before we close.

SJ: I think I’ve covered the things I’ve thought about. It’s been a deep pleasure to participate. I am very flattered to have been asked, and it’s a nice opportunity to reflect, on your life, in a way that doesn’t become as public as this will, I guess. So, it’s been a lot of fun and it’s satisfying, for those of us who haven’t done more public things, and so, thank you.

JBG: Thank you. And with that, I will end our recording.

SJ: Okay.

[file ends 1:22:34]