Born in Lahore, Pakistan, Shazia Azim studied at Kinnaird College for Women before going to Oxford to read for a second undergraduate degree in PPE (philosophy, politics and economics). She went on to LSE to take an MSc in econometrics and then worked in Investment Banking for 17 years, including a ten-year stint at Goldman Sachs. Post the Global Financial Crisis, she embarked on a consulting career and has been at PwC since 2013 where she is now Partner, Financial Services. Azim is also a strong supporter of the Rhodes Scholarship, serving on selection committees and driving the move to reinstate a second Rhodes Scholarship for Pakistan. This narrative is excerpted from an interview with the Rhodes Trust on 8 January 2025.

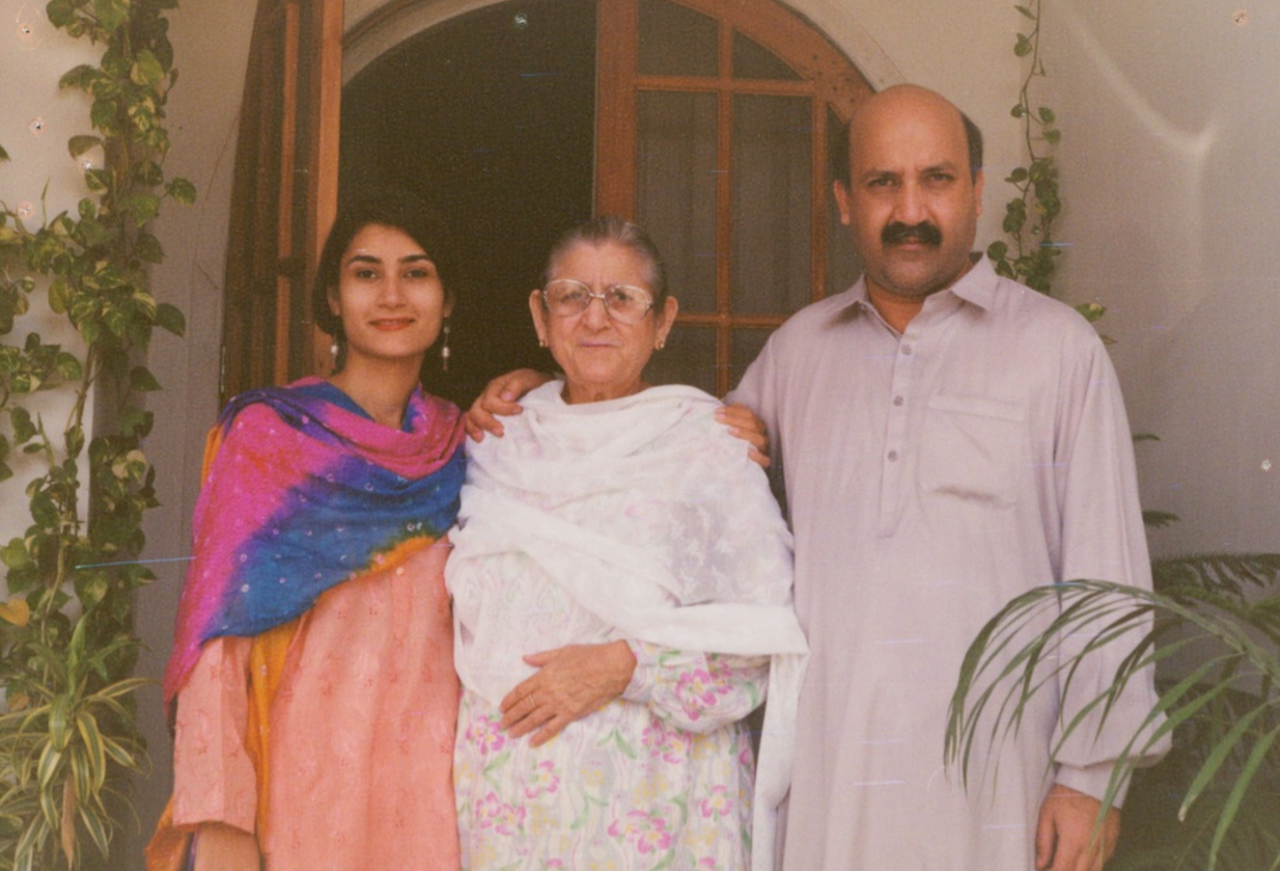

Shazia Azim

Pakistan & University 1993

‘I had complete permission to express myself and ask questions’

I was the last of five children and there was a big gap – 15 years – between me and my nearest sibling, so, it felt like I had six parents. I was spoilt rotten, and I grew up being quite a precocious child, which can be brilliant but is not always helpful. I had complete permission to express myself and ask questions, to be provocative, and I think that is quite a powerful way of bringing up a young child.

I led a bit of a peripatetic childhood. My father was a diplomat, so I went to school in Islamabad, Delhi, and Lahore and spent a considerable amount of time in different places in Asia. By the time I was ten, I was a reasonably international child, and I learned very quickly how to make friends and get used to new environments.

I was very curious in school and very bookish. I was also a bundle of energy. So, I spent a lot of time reading, playing squash and horse riding. I was growing up in the 1970s, so there was a big gender demarcation about what girls should be doing and boys should be doing. As Rhodes Scholars, we talk a lot about fighting the world’s fight: well, I was fighting a fight about gender, the role that I was supposed to play versus the role that I wanted to play. Girls at that time were supposed to do things like music and sewing and cooking, and most of those, I was terrible at. Boys got to do all the fun sport, maths, physics, and playing chess. This was where being the last of so many children was a real bonus, because my parents clearly thought, ‘We can take a risk with her. We will help her do what she wants rather than what society thinks she should do.’ I will be forever grateful to my parents for that.

On applying for the Rhodes Scholarship

I was very interested maths and physics, and I planned to become a scientist. But when my father died, we had to move districts, and although I had come top where we lived before, those marks were not enough to get me into the sciences in our new district. So, I moved into doing double maths and statistics and eventually, into economics. Kinnaird, where I went to college, is an outstanding institution with a reputation for nurturing and mentoring women. Here was where I started to understand economics and fall in love with it. I had incredible women tutors and mentors, and it was hugely motivating to receive that level of sponsorship and guidance about the art of the possible.

I knew I wanted to study in a different country and see the world, but my family didn’t have the money to fund a degree in the US or UK. So, I was given the ad for the Rhodes Scholarship. The criteria were very strict, and Pakistan only had one Scholarship, but I thought, ‘Okay, well, I’ll give it a go.’ I didn’t get it the first time around, but the second time, I was successful. I remember that there was not a single woman on the selection committee, and the interviews were very, very tough. The committee was made up of the Pakistani intellectual elite, including Wasim Sajjad (who became President later on). But it was such an incredible interview experience, being able to talk about everything from education through politics to books and extracurricular activities.

‘Not being told what to think was astonishing and utterly liberating’

Going to Oxford was the first time I had ever travelled on my own. I remember turning up with a few books to read, an inability to cook, and a suitcase full of completely inappropriate clothing for the UK weather and Afghan contraband cigarettes. It was very daunting, but it was also a beautiful place and there was something magical about it.

At first, my time in Oxford was lonesome. I was the only Scholar from my country and everyone else already had friends and networks. And the University food was just awful. But the Rhodes Scholar community did give me the chance to meet people from very different backgrounds and that was amazing. I have a particular memory of when it snowed, and a friend of mine, a Rhodes Scholar from Brisbane, and I ran out into the street and literally lay on the ground to experience it. It was the first time either of us had seen snow.

I did PPE, which is an interesting course. I chose it because it gave me the chance to read things I would never have been able to read in Pakistan, like Karl Mark and Joseph Raz. I absolutely loved the tutorial system. The power of being allowed to have a discussion and not being told what to think was astonishing and utterly liberating.

The Rhodes Trust was very generous in giving us the chance to travel, and I received a grant to travel and study the UK’s Roman history. I also went to Switzerland and France on a reading retreat. I think that’s how I fell in love with Europe, because travelling really opened my eyes to the world and different cultures.

‘Going from one industry to another takes hard work and grit’

After Oxford, I studied at the LSE. It was a very different experience – class-based, and hugely quantitative – but equally enriching. I joined Goldman Sachs straight out of LSE, and the appeal of investment banking was how it converged with what I had been studying. With the financial markets, you had the confluence of political and economic influences which had an impact on how interest rates, stocks and bonds responded to these events. I loved it, and I found it so intellectually rewarding. It was a very male-dominated space, but in a way, studying maths and physics as a child, I was already used to being the only female sitting around the table. At Goldman Sachs, I think I was genuinely the only woman of colour on the trading floor, but at that time, being in a minority didn’t really bother me as such. Places like Goldman Sachs focus on rewarding talent and I was very well looked after.

I think the hardest thing that I’ve done in my career was make the decision to switch from investment banking to consulting. I’ve remained in financial services, so the subject matter is the same, but the way you do things is very different. Going from one industry to another takes a lot of hard work and it takes grit.

The more senior you become in your industry; the more leadership becomes a big part of your job. Instead of your career being about your individual performance, it’s about the team, today and tomorrow, and it’s about how you retain people and how you motivate them to do the best thing for the community. I think you really do need to embrace the leadership and mentoring aspect, in addition to the intellectual and performance aspect.

‘There is no such thing as a singular path’

I think the Rhodes Scholarship gave me the confidence to realise that there is no such thing as a singular path One of the projects I’ve been very closely involved with in recent years is the move to reinstate a second Rhodes Scholarship for Pakistan. I could see the potential in my country, and I wanted others to have that opportunity. I’ve also loved seeing how the Scholarship is extending beyond the cohorts that we have, for example, in places like West Africa. I genuinely care about the Rhodes community. It’s interesting and impactful, it’s diverse, and the way that Rhodes Scholars are taught to think is a very good thing for the world.