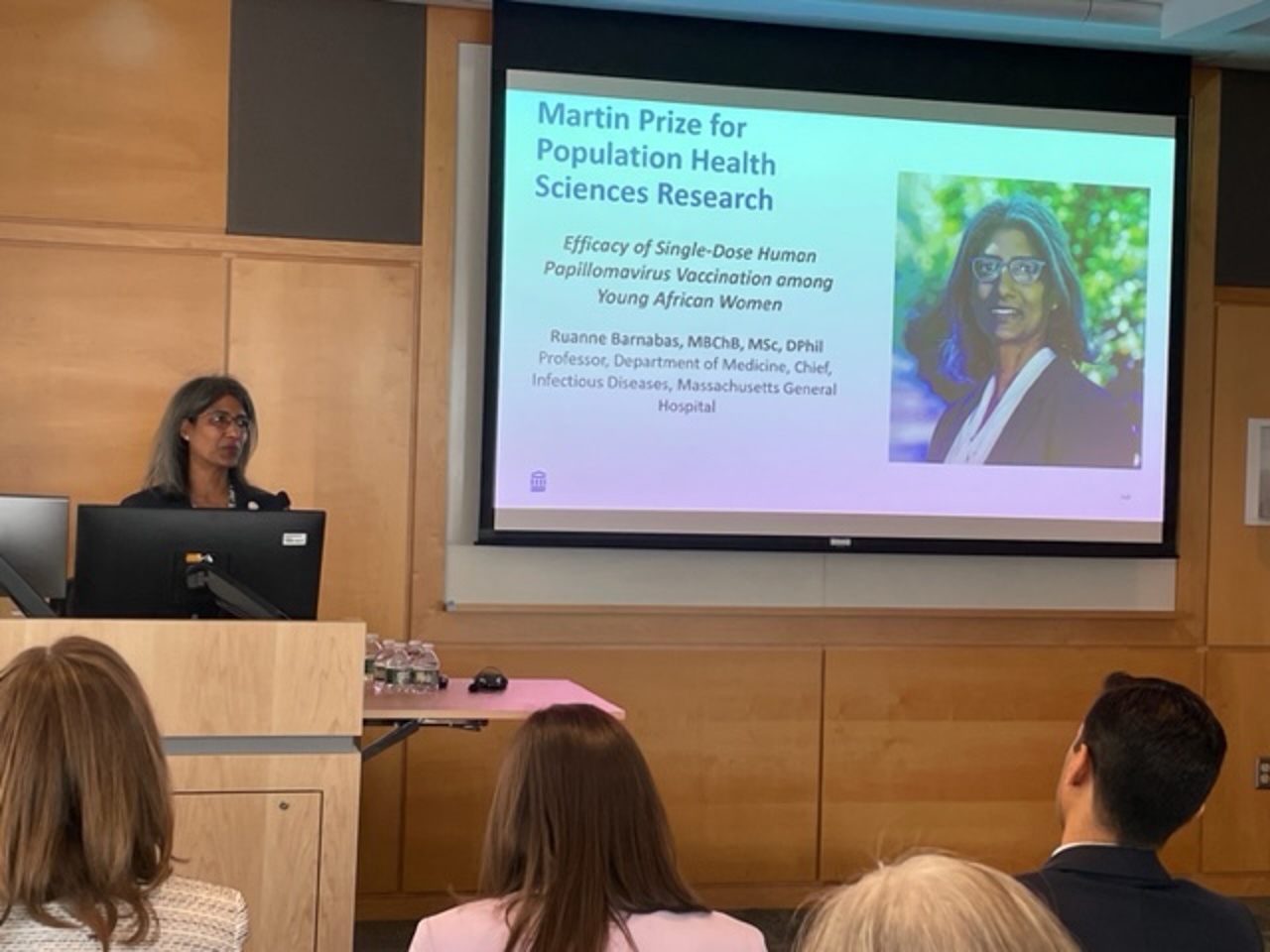

Born in Durban, South Africa, Ruanne Barnabas studied at the University of Cape Town and completed her medical residency in South Africa before going to Oxford to read for a master’s in epidemiology, evolution and control of infectious diseases. She took her DPhil in medicine and clinical epidemiology at Oxford and then held a fellowship at the University of Washington, going on to join the faculty there. Since January 2022, Barnabas has been Chief of Infectious Diseases at Massachusetts General Hospital. This narrative is excerpted from an interview with the Rhodes Trust on 11 April 2025.

Ruanne Barnabas

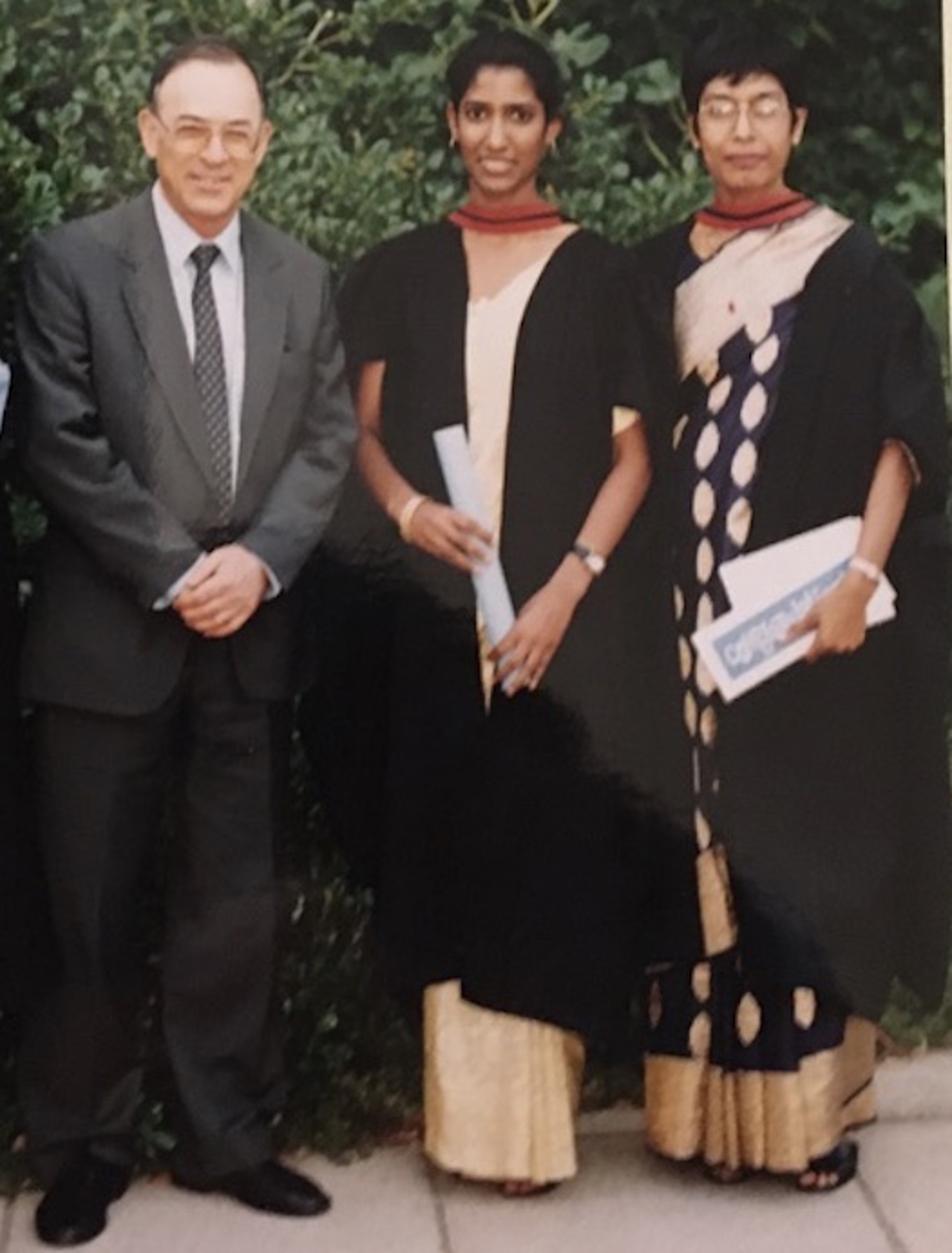

KwaZulu-Natal & Merton 1999

‘My parents worked very hard to help us see that the world could and should be different’

As a young child, I grew up in quite a busy inner-city neighbourhood during apartheid, surrounded by family throughout the city and in neighbouring towns as well. It’s hard to imagine how segregated the world was then. We moved to an Indian suburb and I went to an Indian school where we had only Indian teachers. We could only go to Indian beaches. We shopped at Indian shops. You could shop at other shops but, for example, if you wanted to buy clothes, you couldn’t try them on the dressing room or use the restroom.

But our sense of community our values and sense of what was right in the world really trumped all those political circumstances. We were raised knowing that people were equal and that they deserved human rights, that they deserved health as a human right. My mum was a medical doctor, working in public health and that’s undoubtedly where my interest in medicine comes from. My parents worked very hard to help us see that the world could and should be different. They were very attentive to our education and we read books that were smuggled in from Zimbabwe and other places. There were also so many allies, like the white librarian who found a loophole so that Indian children could check out books from the white libraries, and retired teachers who would help us learn to use dictionaries and other reference books.

My dad was a botanist and we spent a lot of time in nature. Part of my parents’ childcare plans included going with my dad to the university and hanging out in the labs while he taught students there. I even had my own little microscope to look at specimens. And when I drew what I saw, I remember my dad only giving me nine out of ten because I hadn’t included the labels. That was where my understanding of scientific method started, alongside our academic education. At school, I had wonderful teachers, and my maths teacher in particular had a really important impact on my life, helping me think about how to solve complex problems.

On applying for the Rhodes Scholarship

I studied medicine at the University of Cape Town. My parents thought I should choose a less hectic life, but I was very determined. For me, public health was the driving force behind that. The idea that through vaccination you can prevent almost half of all deaths under the age of five, for example, just blew my mind.

We had a great cohort in medical school and we did a lot of fun things together. Of course, we were also part of the resistance, the group of students fighting apartheid. We wanted a different world, and that gave us a lot of energy. I had done my International Baccalaureate before university at the Lester B. Pearson United World College on Vancouver Island in Canada. That was a very supportive community for me, and then, too, University of Cape Town was very progressive.

I remember I was working as a junior doctor on an obstetrics and gynaecology rotation and a patient came in who was pregnant with twins and about to deliver. She had not had any prenatal care. I tried to ask how that had happened but the nurses around me told me just to get on with delivering her babies. I wanted to be taken seriously in public health, so I found a course on the mathematical modelling of infectious diseases at the Wellcome Trust Centre in Oxford. When I emailed the head of the course, he said he was actually in Durban and he offered to meet. He encouraged me, and that was why I applied for the Rhodes Scholarship. What I remember especially is how wonderful the interviewers were. I really enjoyed the conversation we had. I had a picture in my head of what a Rhodes Scholar was and I didn’t match that picture, but I was just absolutely thrilled to be part of it.

'I got excellent help and a lot of support’

It was so exciting to travel to Oxford and arrive there. My college, Merton, does a great job of helping freshers settle in. One of my really important memories is that adapting for the cold was quite new, and Merton gave us good advice about buying a hat and gloves. I became the social secretary there, and we’d host parties and have a lot of fun. I met some of my closest friends for life during my time at Oxford. I have very fond memories of punting, which I loved. Music was wonderful too, especially the chapel services, where the music would carry you into a different space.

The academics at Oxford were really hard, much harder than I had realised they would be, but I got excellent help and a lot of support that eventually allowed me to do very well and graduate with honours. I went on to do my DPhil on mathematical modelling of the effect of the human papillomavirus (HPV) and that is what I continue to work on to this day. Some of the model code that I wrote then, we still use in my group for modelling, designing clinical trials for HPV vaccines. And I am still in touch with my DPhil supervisor, who has been a brilliant mentor. 25 years later, I still tap him for advice.

‘Pushing the boundaries of science is immensely rewarding’

After Oxford, I knew that I wanted to do a postdoc and my supervisor suggested I should go to the University of Washington, which was the best place to work on sexually transmitted diseases and HIV. I had been a junior doctor when we started to see the first cases of HIV and that had an enormous, formative impact on my life, because patients my age were dying and there was really nothing we could do. It was just heartbreaking. At the University of Washington, I started doing clinical trial work, and my work has grown to the point where I now lead a suite of clinical trials. I used the data from them to parameterise mathematical models which help us understand the impact of interventions at population level.

I have a stream of work that is about access to care where we really focus on patient-centred interventions. In the case of HIV, for example, we’ve done a number of studies that have demonstrated that providing care in the community, either through mobile vans or at home, has a bigger impact on treating HIV. Just overcoming all the logistical barriers makes an enormous difference. We also have another study which focuses on just making prevention access as simple as possible. And alongside the net health benefits, patient-centred access is also very cost effective. The other exciting work that we do is in HPV vaccinations. As a result of one study that we led, more than 60 countries around the world have changed their guidelines to single-dose HPV vaccination and 18 million girls to date have been vaccinated who wouldn’t otherwise have been.

One of the biggest challenges is to change the way we think about vulnerable people, to recognise that any one of us could be vulnerable at any time in our life for reasons completely unrelated to our character or baseline abilities or willingness to work. You have to have a pragmatic approach, and to be able to do this work every day is a gift. Pushing the boundaries of science is immensely rewarding. Passing on our discoveries is also so important, and one of the main reasons I applied for my current job was to be able to share our methodology and training. There’s so much work to do in every sphere, and my leadership style is about asking, for every decision, ‘Is that aligned with our values?’

‘You only have the day you have’

When I’m not working, I love being with my husband and kids. We spend a lot of time outdoors together, skiing and surfing, and I also really enjoy cooking and entertaining. I have to say too that one of the reasons I love surfing is that I’m terrible at it! Being able to try and fail is very important.

To today’s Rhodes Scholars, I would say that part of being at Oxford is realising that your time there is finite. You only have the day you have. We tend to think about intellectual work as something you do in the silence of the library, but it’s also true that the conversations you have with people are deeply meaningful and change the way you think. And alongside academic work and conversations, of course, you should definitely make time to punt down the Thames!