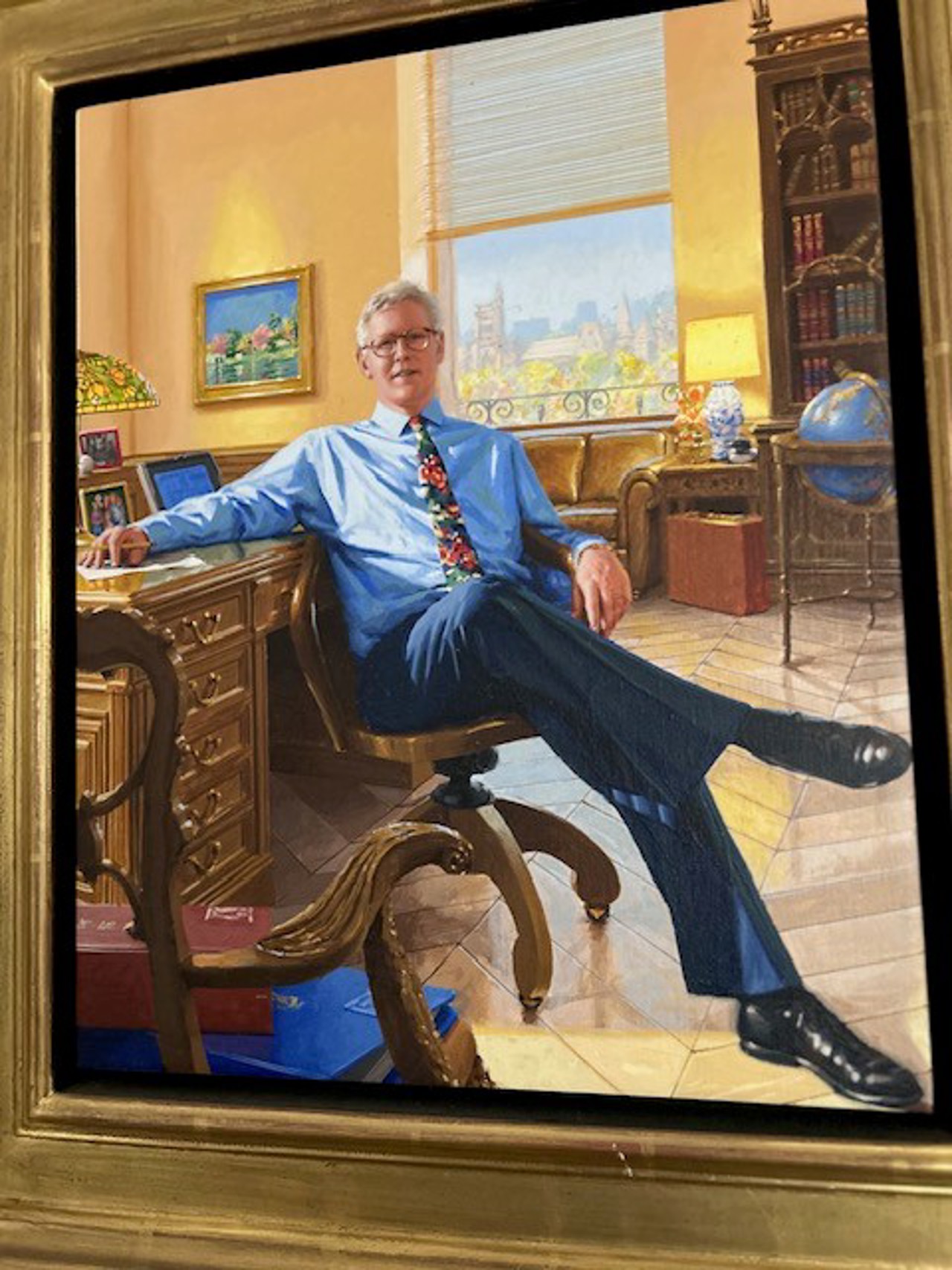

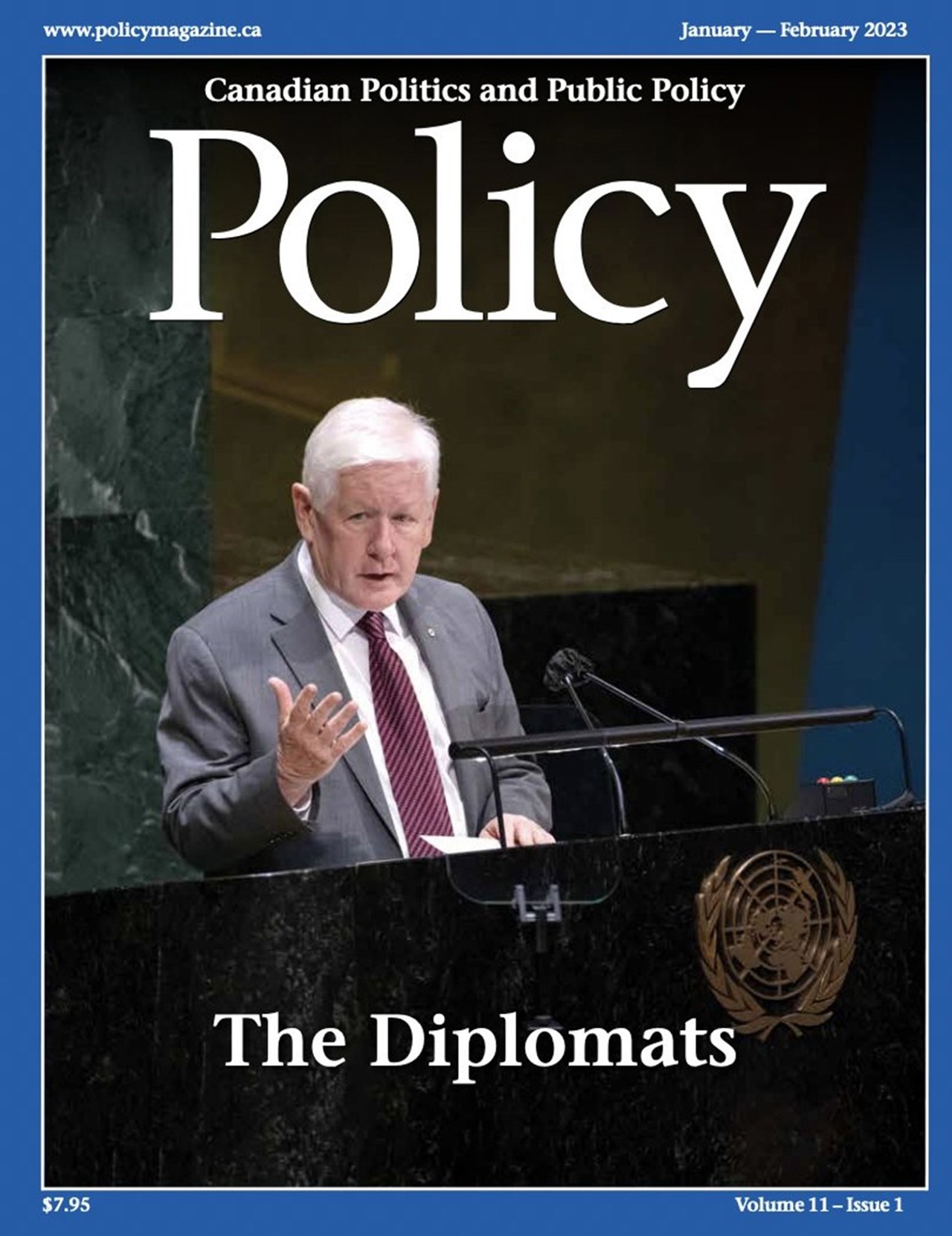

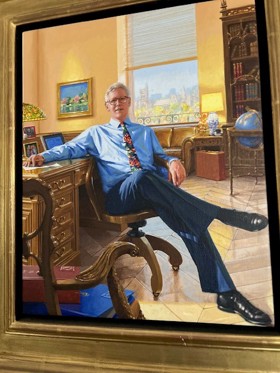

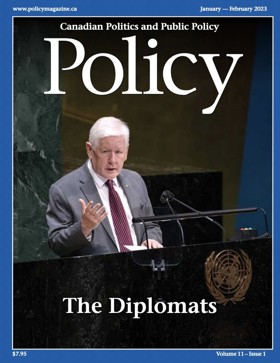

Born in Ottawa in 1948, Bob Rae studied at the University of Toronto before going to Oxford to read for a MPhil in politics. Returning the University of Toronto, he graduated from the Faculty of Law, going into legal practice and then entering politics. Between 1978 and 2013, Rae was elected to federal and provincial parliaments 11 times. He was Leader of the Ontario New Democratic Party from 1982 to 1996, premier of Ontario from 1990 to 1995, and interim leader of the Liberal Party in Canada from 2011 to 2013. In 2020, Rae was appointed Canadian Ambassador to the United Nations. This narrative is excerpted from an interview with the Rhodes Trust on 24 June 2024.

Robert Rae

Ontario & Balliol 1969

‘It really put me into an international frame of thinking’

My parents had met at a summer school in Geneva. My mother was English and my father had actually studied at the LSE and in Oxford. After that, he joined the diplomatic service and during the war, he served in Algeria and in Paris. I remember that we travelled to England when I was very little and then we came back to Canada in 1952. My dad served as Lester Pearson’s executive assistant when he was the President of the General Assembly in New York.

When I was eight, we moved to Washington, DC where my father was working and I made great friends at public school there that I’m still in touch with. I also fell in love with baseball and I’ve always enjoyed participating in sports. We were in Washington at the beginning of the civil rights movement and at school, I was I was a very keen student of American history and politics. I would drag my parents round all kinds of civil war sites and public buildings in Washington and I remember staying up on the night of the election in 1960, watching the returns until President Kennedy was finally declared the winner.

My dad was posted to Geneva as the ambassador there when I was 14. I went to an excellent international school and I had to learn French because I didn’t speak a word of it. I think in many ways that was probably the most important educational experience that I had. It really put me into an international frame of thinking – multicultural, multilingual, multiracial, multireligious – that very much became part of my life.

On applying for the Rhodes Scholarship

My undergraduate experience at the University of Toronto was pretty wonderful. Radicalism was in the air and I went on marches about Vietnam and had a very powerful experience when I met Trevor Huddleston, an Anglican priest who was one of the leaders of the anti-apartheid movement. My main area of activity was writing for the varsity magazine and I also went on to the Students Administrative Council and became the University Affairs Commissioner. I was the last of the cohort of students at the University of Toronto who did what we called the honours programme where you had much more defined courses. I had great teachers, especially in history and intellectual history and in political science.

I knew I wanted to go to England to study, although there were some doubts in my mind about what I was going to do and where it would lead. When I won the Rhodes, the president of the university wrote to congratulate me but said , ‘I’m quite surprised that somebody of your advanced egalitarian views would be applying for such an elitist scholarship.’ I said, ‘You know, all scholarships are elitist.’ In fact, I really do believe that if women had been allowed to apply for the Rhodes Scholarship in 1969, I would not have got it.

‘I really liked that atmosphere’

Balliol was a fantastic place. It was wonderfully open, although, like the Rhodes Scholarship at the time, it was all men, which was crappy. But the college was quite international in its makeup and I really liked that atmosphere. There were a lot of the Rhodes community who hung around just with Rhodes people, but I got to know other people at Balliol, including the undergraduates.

The first term was unforgettable. My director of studies in Balliol, Bill Weinstein, saw me and my tutorial partner and said, ‘Well, we’re going to throw you in the deep end. You’re going to go for a two-hour tutorial every week with Isaiah Berlin, doing the paper on Marx and Hegel.’ We thought, ‘Holy crap, we’re into it now.’ We went all the way up to Wolfson College to meet Sir Isaiah, as he then was. He could not have been nicer. He started talking about Hegel and eventually he said, ‘Mr Rae, what’s that there,’ pointing at the floor. I said, ‘Oh, a carpet,’ and he said, ‘anything about it that strikes you? Let me tell you something: look at the design, everything fits.’ I said, ‘Oh, okay, everything fits,’ and he said, ‘In political philosophy there are two kinds of people. There are the people who think everything fits and there are people who think, “No, everything doesn’t fit.” So, you will have to decide, which are you?’

I had other wonderful tutors as well, and I began to develop a strong interest in jurisprudence. But as time went on, I still wasn’t sure about what I wanted to do. I decided to stay for a third year, then changed my mind, then went to the US and came back to Oxford. I was becoming very wound up in thinking about what I was going to do and also about certain philosophical issues and I began to feel more and more inadequate about my ability to work my way through this world. I went to London to stay with some friends and I started showing real signs of having what I guess you’d call a breakdown. Luckily, my friends were very helpful and kind to me, but I mention it because I think sometimes, when you’re a Rhodes Scholar, you think you should be just fine, perfect.

‘I realised it was an important part of my vocation’

I ended up going to work in London at a legal aid centre in Islington, which at that time was not a very upmarket place. I’d left Oxford with my tail between my legs, feeling a bit ashamed. But then one day, I was back there, walking down the street and basically going through this process of saying ‘Goodbye,’ and Isaiah Berlin saw me. He said, ‘Rae, how’s it going?’ and I said, ‘Actually, not very well. I really don’t know what I want to do.’ He pulled me aside and said, ‘You need to know something. Not everybody’s cut out to be an academic. I had many doubts about it myself and the happiest moments that I spent in my career, I was involved in politics.’ He’d been an advisor to the British government, and he said, ‘That time in Washington was the most exciting, most interesting time I’ve spent, so maybe that’s your vocation.’

I went back to Toronto and I went to law school. I was very determined to make Canada my home. If you look at my career, I’ve been all around, and one of the great things I realised about Canada is that nobody has to fit in: everybody comes from everywhere, in some way. I believe that multiculturalism is critically important.

My transition from practising law to a political life happened very quickly. I got called to the Bar and I was running for political office at the same time. It was just something that came along, when someone I knew who was an MP said, ‘Look, we thought maybe you’d be a good candidate.’ I was engaged at the time and Arlene said, ‘Sure, let’s try. Why not?’ When I got into it, I realised it was an important part of my vocation.

‘We have to engage outwardly as well as inwardly’

The hardest thing about what I do is when there are situations with a level of poverty, a level of deprivation that has led to an absence of hope. I find that very, very difficult. You feel, ‘Well, what can I usefully do?’ I think hope is about having a vision for what can be and the steps you have to take to get there. But you also have to accept that in many situations, people won’t come to you or won’t accept your advice or what you’re trying to offer. These days, I worry about a political trend towards isolationism and nationalism. We have to engage outwardly as well as inwardly. I grew up in a household that was very committed globally, and I think that’s very important.

In terms of advice to others, the only thing I’d say is that whenever you’re faced with a defeat, rather than blame other people or blame the world in some way, it’s always useful to look back and ask yourself the question, ‘What could I have done differently? What could I have changed in my own behaviour?’ At Oxford, I realised had a neurosis that was preventing me from being productive, and that’s something you have to work on. Now, I’m actually quite a happy person, and I’m careful to talk to people about mental health, the warning signs and how you deal with them. I had a hard time, but there are ways of learning how to get better, if you become more aware.