Born in Los Angeles in 1958, Robert Maloney studied at Harvard before going on to Oxford to read for a second BA in PPE (philosophy, politics and economics). He completed his medical degree at the University of California, San Francisco and Johns Hopkins Hospital, and is now Clinical Professor of Ophthalmology at UCLA and a surgeon at the Maloney-Shamie Vision Institute in Los Angeles, California. A pioneer in the field of vision correction surgery, Maloney has received numerous awards for his distinguished contributions to medicine and he continues to develop new technologies for vision correction. In 2024, Maloney joined the first cohort of Oxford Next Horizons, a six-month experience for those in mid to late career, offering the chance to think, explore and reinvent. This narrative is excerpted from an interview with the Rhodes Trust on 20 June, 2024.

Robert Maloney

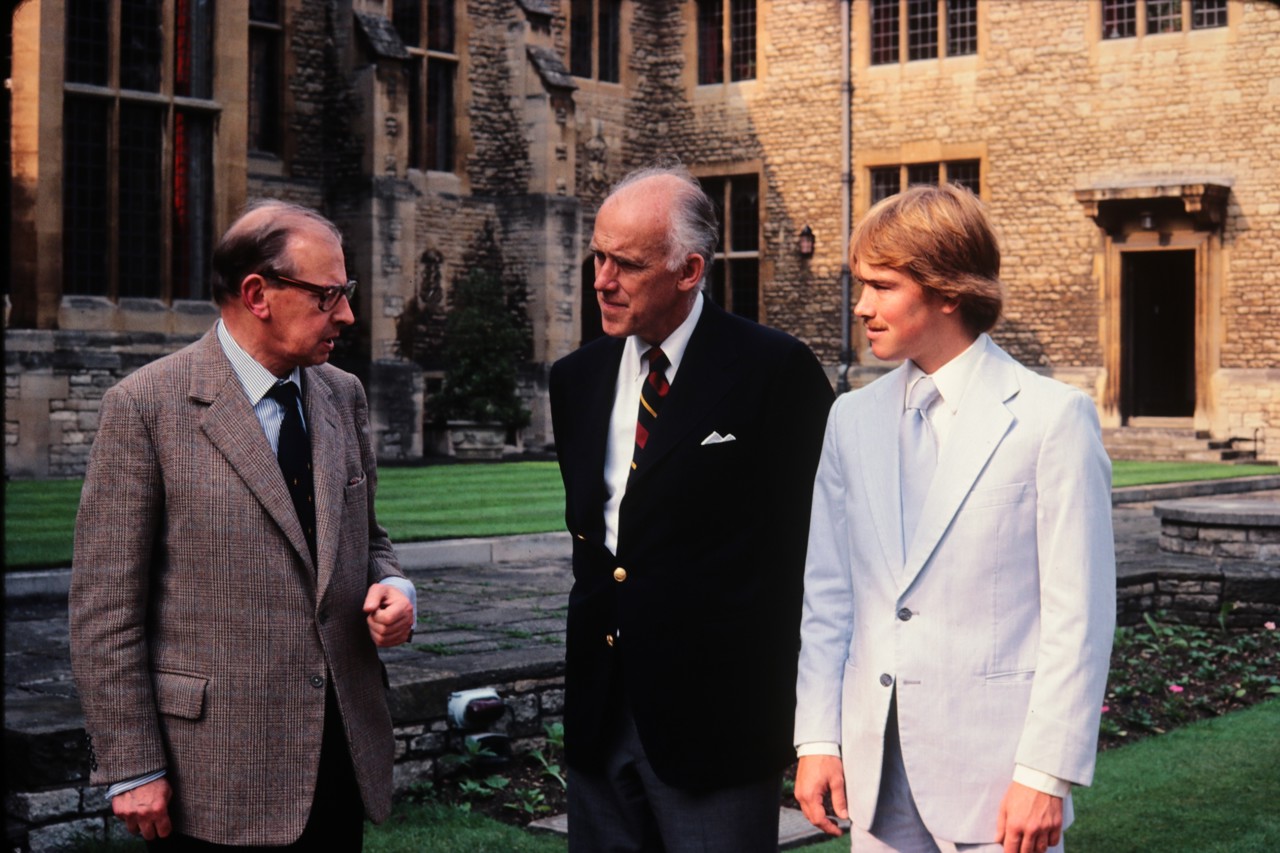

California & Magdalen 1979

‘I made a great decision for the wrong reason’

I’m the oldest of four children, and I would say that as a child, I was a classic oldest: driven, hardworking, parent-pleasing and a follower of the rules, although that last one faded as I got older. My father was a pioneering cardiac thoracic surgeon and my mother stopped working outside the home once she was married. My father and I would have these debates over family dinner, which my siblings remember more as intellectual arguments. We grew up in a sprawling, slightly decrepit house in Los Angeles, and we’d just play in the streets.

My father was certainly a formative figure in my life. He had been a Naval officer, and he raised us like we were Navy cadets. We were expected to obey, and there would be consequences if we didn’t, but there was nothing arbitrary about his discipline, and the boundaries were clear. I must have been about five years old when I decided I wanted to be a doctor. It’s not a good way to pick a profession because your father does it and he’s your role model. But that’s what I did, and it worked out well for me: I made a great decision for the wrong reason.

That thread of discipline continued for me at school. I went to a Catholic grammar school where I was taught by nuns. It was a lot of rote learning, and I didn’t find that at all interesting. But then, I had a sixth-grade teacher who saw that I was really good in math. She sent me to the cafeteria with a textbook and let me work at my own pace. Later, I had a fabulous physics teacher in my senior year of high school who did the same thing. So, I fell in love with physics, and in college, I was a math major with, effectively, a physics minor. Those two teachers made a huge difference in my life, by recognising that not all students are the same.

On applying for the Rhodes Scholarship

I’d like to say that applying for a Rhodes Scholarship was a lifelong ambition of mine, but that wouldn’t be true. What actually happened was that I had been awarded a Rotary Fellowship to go and study in France. At the time, I was in college and short of money. My grandmother, who was a very wise woman, sent me $200 in an envelope and said I could keep it if I applied for a Rhodes Scholarship. So, she bribed me, basically, and I needed the $200 much more than I needed the time it took to fill out the application.

I didn’t understand at first how big a deal it was, but as I went through the application process, I started to realise. And so, when I won the Scholarship, I didn’t have a moment’s hesitation about relinquishing the Rotary Fellowship and becoming a Rhodes Scholar. I understood that it was an opportunity to broaden myself as a person. At Harvard, I went through in three years, and I did almost nothing other than maths, physics or pre-med courses. My goal at Oxford was to think about the meaning of life, so I was interested in studying philosophy particularly.

‘I grew up’

My plan just didn’t work out in terms of my academic work at Oxford. I had thought that philosophy was the formal study of the things that I talked about late at night with my roommates over a beer, such is, ‘Why are we here?’ ‘What is ethical? What is not?’ When I got to Oxford, I was taught Anglo-American analytic philosophy, which was very strictly limited at the time, and focused on questions that I really was not interested in.

Because I wasn’t interested in the material I didn’t work very hard. Sir Edgar Williams, who was Warden at the time, wrote to my selection committee at the end of my first year, and said, ‘Mr Maloney has had a good time this year, perhaps too good a time.’ And it was strikingly accurate, I have to admit. It was embarrassing, but he was right. I spent a lot of time travelling, and over the course of the two years, I went to India, Sri Lanka, Nepal, Indonesia, Malaysia, Thailand, France, Greece, Yugoslavia, Switzerland and Scotland. I also made a group of really wonderful friends, and I grew up. I like to think that I was still in some way a credit to Cecil Rhodes, who also did not work very hard when he was at Oxford. Yet, in a weird way, I achieved exactly what I wanted to achieve, which was to broaden myself socially and emotionally. I just didn’t do it through my studies.

‘I’ve never followed the herd’

When I went to medical school, I thought I’d be a neurologist. It’s such an interesting area. But I soon realised that working with patients who are struggling when their brains aren’t working properly was just emotionally really hard for me. I got talked into ophthalmology when I was on a late shift one time, and someone caught me at a vulnerable moment. That someone gave me a career and also became one of my best friends. It really was a gift.

That’s not to say it was easy. When I started my career, the idea of eye surgery to get rid of your glasses was only just getting started. I had always hated wearing glasses, so I was really interested in this, and also, it’s all about math and physics. So, I immersed myself in the field. But I was mildly reviled for it. It was considered a waste of time. The reaction of organised ophthalmology at the time was, ‘If you can see perfectly well in glasses or contacts, why would you take the risk of doing surgery?’ which seemed a reasonable question on the surface. But really, it comes down to it, the reason you’re wearing glasses or contacts is because your eyes don’t work properly, and refractive surgery is about making them work properly again.

Even when I got to UCLA, there was still this sense of, ‘Why would we have somebody who does this sort of thing at our institution?’ But I’ve never followed the herd. I’ve always had a personality where I go in my own direction, and it’s why I pissed people off along the way. I often butted heads with people, but I never gave in to them. I went into this field that was controversial and considered unethical by a lot of people and helped turn it into a field where it’s a core part of medicine. It’s so core now that residents physicians are required to learn this surgery for a programme to be accredited. It has gone from heresy to canon in a generation. I’m proud that I didn’t let anyone stop me from working on that.

I think of my life as having had a series of major inflection points. Professionally, the biggest was certainly leaving UCLA to start my own laser centre. Personally, it was meeting my wife and the births of our three children. I would say that coming back to Oxford for the Oxford Next Horizons programme is another inflection point. I’ve spent the six months here doing a research project, and I’ve really fallen in love with the history of medicine. Now, I just have to take that with me and see where I end up.

‘Choose your own path’

The advice I would give young Rhodes Scholars is: don’t take advice from people like me! Choose your own path. And do not let the Rhodes Scholarship make you think that you have to decide first on a career in service, such as environmentalism or social justice. There is such pressure on you to serve, some externally imposed, a lot self-imposed, and it makes for a grim life if that’s not how you’re wired. So, follow what you’re passionate about, and then figure out a way to serve while doing what you love. You only get one life, and there are all kinds of ways to serve.

I’ve helped a whole bunch of people to get rid of prosthetic devices to allow their most important sense to function. You could say that allowing people to get rid of their glasses and contact lenses isn’t that big a deal, but that’s only because people are so used to glasses and contacts that we no longer think of them as prosthetics. I didn’t go into it thinking, ‘I want to serve.’ I went into it because I loved the work and was fascinated by it. So, figure out what you love to do and are great at. Then figure out how to serve.