Born in Babylon, Long Island in 1945, Richard Schaper attended Colgate University before coming to Oxford to begin a second undergraduate degree in PPE (Philosophy, Politics and Economics). He returned to the US and studied philosophy and religion at the University of Chicago and Yale before entering a Benedictine monastery for eight years. Schaper then became involved in pastoral care for cancer patients and those suffering from AIDS, and went on to be ordained a minister of the Lutheran Church. Now retired, he continues his ministry alongside his abiding love of sailing, and he has also trained as an expert in financial planning. This narrative is excerpted from an interview with the Rhodes Trust on 29 May 2024.

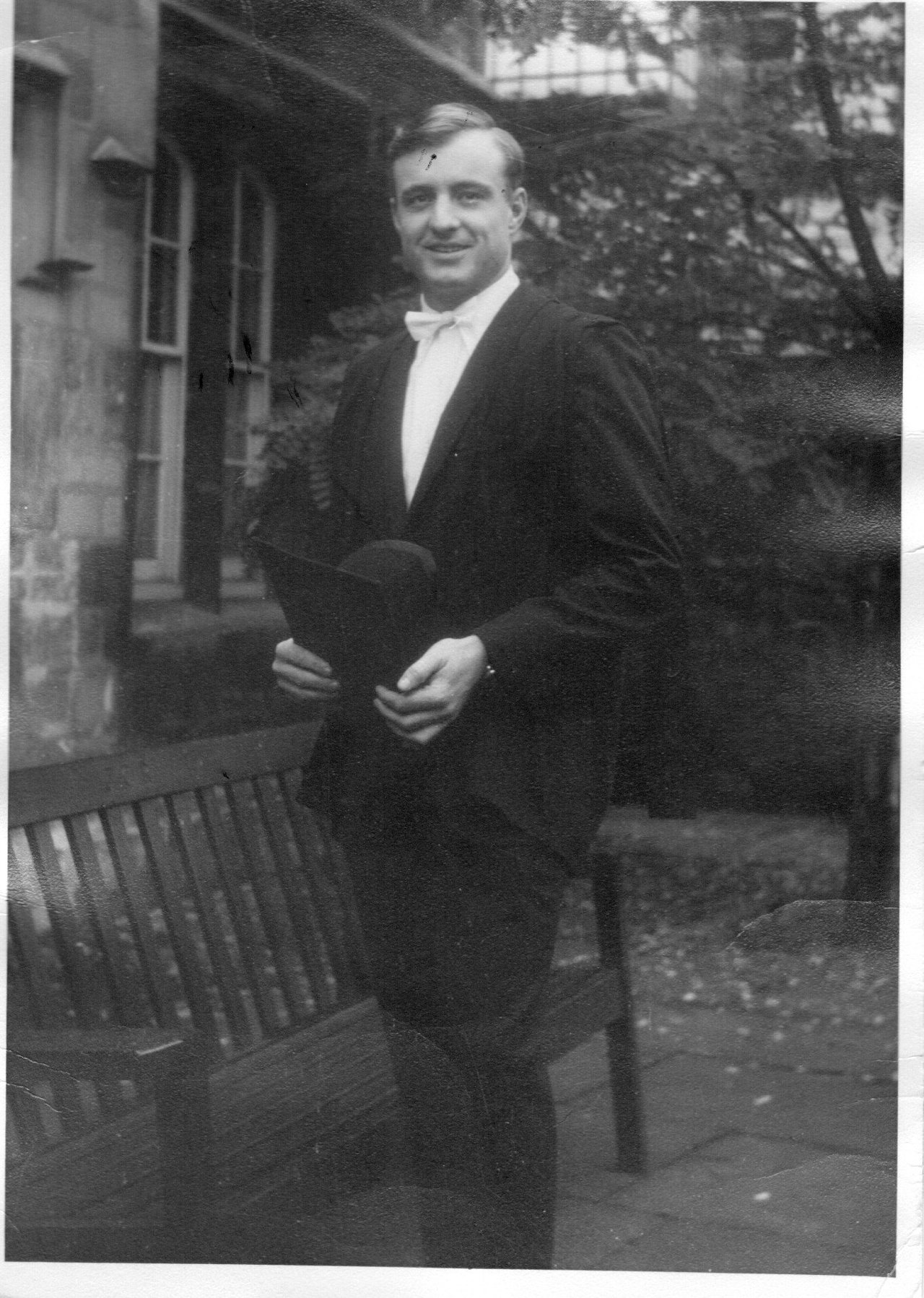

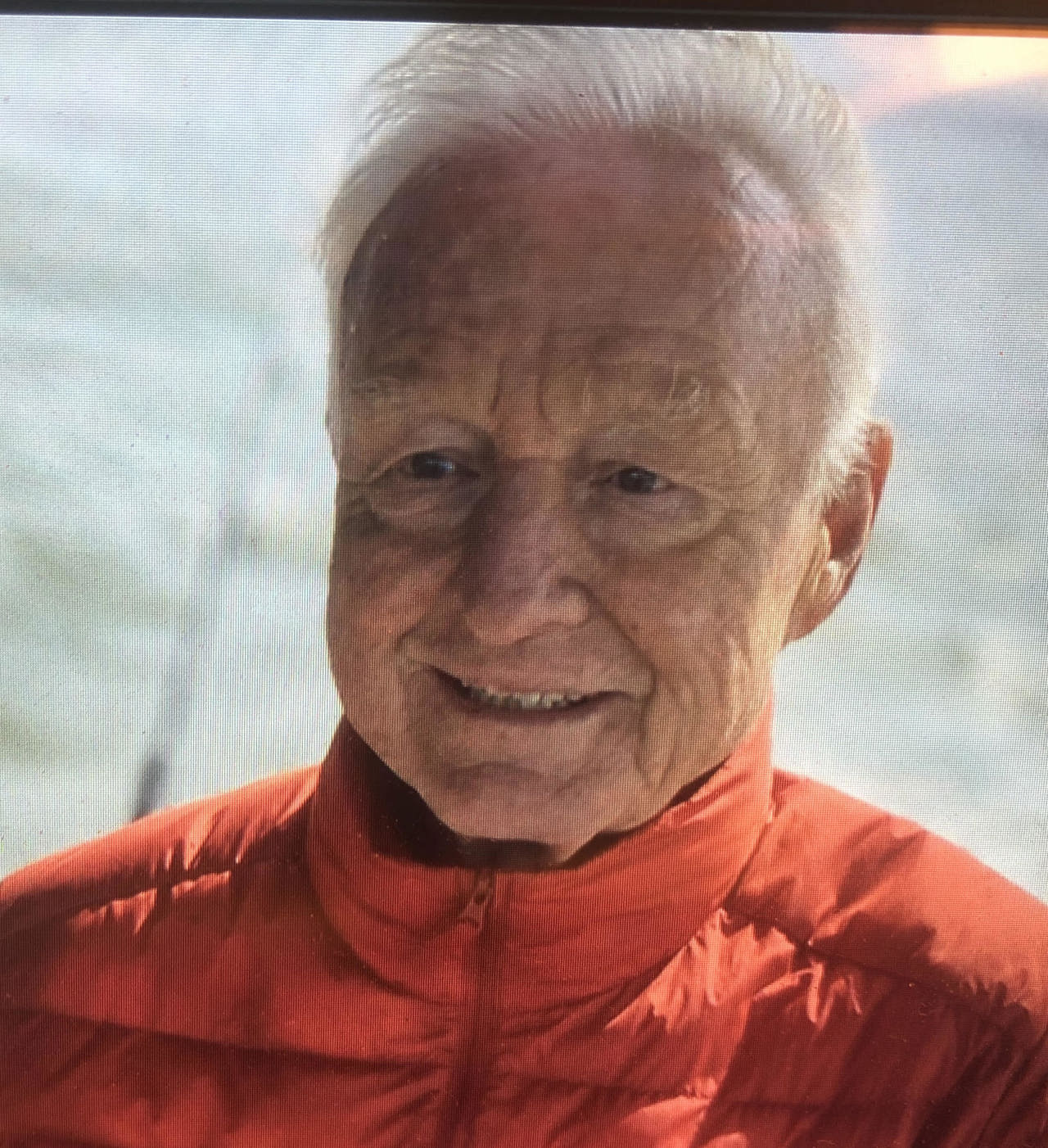

Richard Schaper

New York & University 1967

“Study hard, work hard”

My experience growing up was greatly shaped by the fact that my father was a commercial fisherman. When my grandfather, Peter Schaper, came over from Friesland with his brother, to the US, they fished out of Nantucket in the summer and lived in West Sayville on Long Island. And then, my father and his three brothers all became commercial fishermen, working together in the same fish company, Sunrise Fish Company. So, I grew up working on the fishing boats with my cousins and uncles.

I’m the oldest of five, and we were a very close family. My mom, in particular, really shaped my personality. Neither of my parents went to college when they were younger, but later in life, my mother studied to become a nurse, and she was also a Sunday school teacher and very active in the Lutheran Church. She told me, ‘Study hard, work hard,’ and I did.

At school, I always tried to get the desk right up in front, by the teacher. I enjoyed science, and I also loved sport – especially football – and being outdoors. I didn’t know anything about universities, but my parents were very keen for all of us to college. I won a New York State Regents scholarship, which you could only use for a college or university in New York State, and I chose Colgate. At that time, I was still focused on science, but all freshmen had to take a core course in philosophy and religion, and I sat in the class just stunned. I didn’t know you could ask questions like that and wrestle with these kinds of issues. It was life-changing.

On applying for the Rhodes Scholarship

I remember a professor from Harvard coming to lecture at Colgate, and he defined philosophy as grappling with the foundations of things. I thought, ‘Yes, that’s what I want to do with my life.’ I was also very involved with the civil rights movement and civil disobedience, and that prompted me to ask questions about how society should be. A group of us went down to Virginia to work on voter registration and before we left to head up to Colgate again, we joined hands and sang, ‘We shall overcome,’ and that’s when I found my own faith.

It was the chaplain of Colgate who suggested I should apply for the Rhodes Scholarship. I had no idea what it was, but he convinced me that the interview would be a good experience in its own right. I was really surprised to reach the final round. In my application essay, I’d written about how Cecil Rhodes was a racist, and I remember the panel asking me whether, if I were to be given the Scholarship, I would renounce it as a public demonstration of justice. I said, ‘No, I certainly would not. I would use it to train myself to become more effective in trying to overturn the racist and unjust social structures that made Cecil Rhodes a rich man.’

‘Oxford was a culture shock’

I couldn’t believe it when I actually won the Scholarship. In those days, all the new Rhodes Scholars from the US sailed to England together on the SS United States. It was my first passport, my first time out of the United States. When we got to Southampton, it was dark and it was raining, and they herded us into these big buses to take us to Oxford. When I got off at the other end, I really didn’t know where I was. It was terra incognita, completely.

I cherished the tutorial learning at Oxford. It was so personal. I loved it, and it was something I missed when I went to on to study at other universities in the US. I enjoyed a lot of things about Oxford, but I always felt a little apart from the other students. I remember a conversation with a porter where it was clear I had offended him in some way, but I didn’t know how or why. And then, over a meal in hall at University College, the philosopher Gilbert Ryle asked me about American politics. I tried to answer his question seriously, but he made it clear that he was bored by what I was saying and I felt out of my league. Oxford was a culture shock for me, and having a scout, as they were called then – a servant to make my bed and look after me – was something I found just embarrassing.

After a year, I made the difficult decision to leave Oxford. We were in the hottest years of the Vietnam War at that time, and it looked as if my number was going to come up for being conscripted. I was not willing to serve in that war, but because I wasn’t opposed to all wars, I didn’t count as a conscientious object. That meant I risked being put in jail. But if I went on immediately with my original plan to study theology, I would be given a deferment. So, that’s what I did.

Asking the ultimate questions

I started at the University of Chicago, but moved on to Yale because that was a better fit for my PhD topic. All this time, I’d been suffering from an increasing sense of dis-ease. When I met two Benedictine monks who were working in the peace movement, they told me about a monastic community up in the Green Mountains of Vermont. I went there, and when the monks began singing and praying, the tears just rose up and I couldn’t stop crying. It touched me so deeply, and I felt something in me being brought back to life.

I stayed in the monastery for around eight years, but then, I became very restless again. I wanted to return to my doctoral studies, focusing on the relationship between ethics and the spiritual life, and I was advised to work with a professor at Emory University in Atlanta. To fund my studies, I signed up to a clinical pastoral education residency, working in hospital with terminal cancer patients. It was a such a deep experience, helping to care for patients and their families who were asking the ultimate questions. To be with them, and for them to risk opening themselves to me and talking with me, was very powerful. I decided, ‘This is what I want to do.’

To be ordained as a chaplain, I had to take on parish duties, and I loved that too. This was all happening as AIDS was breaking out in Atlanta, and I became involved in putting together a chaplaincy for people with AIDS. Many of the people I was ministering to were gay. They were Christian and they came from little towns in the South, and their families didn’t know they were gay and didn’t know they had AIDS and didn’t know they were dying. So, it was a real challenge for pastoral care. My writing about that work was published nationally and then globally, and out of that, I was called to be a pastor in San Francisco. It was also while I was training to be a chaplain that I met my wife, Anita Ostrom, who was training for a similar role. We fell in love and got married, and our first child was born soon after we moved to San Francisco.

‘I want to pay forward some of what I received’

I’m retired now, but I still work in ministry, preaching and doing whatever I can to work for justice in the world. Before I retired, I went back to school to learn about financial planning and understand more about the role money plays in society and in our lives. In my own estate plans, I wanted to pay forward some of what I received, so my wife and I have included the Rhodes Trust in our will. The Rhodes Scholarship had a great impact on my life and it also gave me a band of brothers in my classmates who are still a huge part of my life.

I’m so excited about the direction the Rhodes Trust is taking under the current Warden, Elizabeth Kiss (Virginia & Balliol 1983). Every year, I see the new Scholars from the US, and there are so many women now, and so many people of colour, and so many people who, like me, come from backgrounds that were not academic or professional. That’s the way we should be moving in the world. I feel it’s important not to look back, but to look forward, to how the resources of the Rhodes Trust can be a resource to fight the world’s fight in ways Cecil Rhodes might never have imagined.