Born in Montreal in 1948, Robert Calderisi attended Loyola College, Montreal before going to Oxford to read PPE (Philosophy, Politics and Economics). After Oxford, he studied at the University of Sussex and then worked for the Canadian Department of Finance, the Canadian International Development Agency and the OECD. Calderisi went on to a career at the World Bank, holding the posts of Division Chief for Indonesia and the South Pacific, head of the Regional Mission in Western Africa, international spokesman on Africa and Country Director for Central Africa. After leaving the Bank, he became a writer and has authored works, such as Cecil Rhodes and Other Statues: Dealing Plainly with the Past, The Trouble with Africa: Why Foreign Aid isn’t Working, and An Open Letter to the Pope from a Gay Catholic. This narrative is excerpted and edited from a full interview with the Rhodes Trust on 15 April 2024.

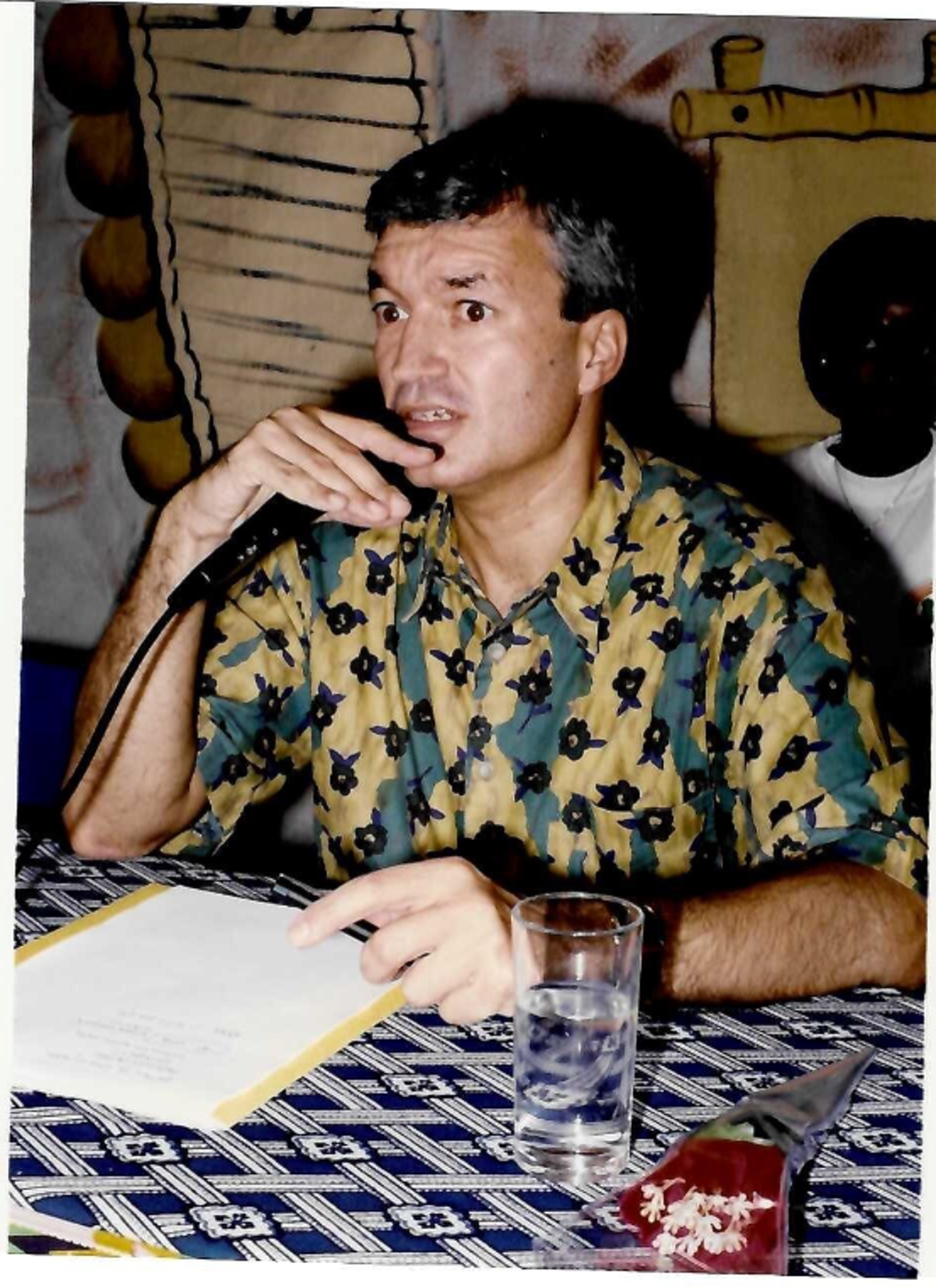

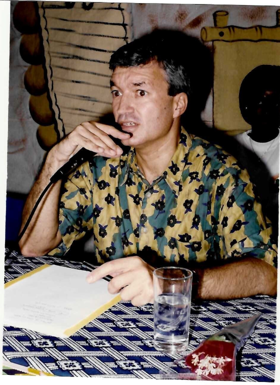

Robert Calderisi

Québec & St Peter’s 1968

‘My parents worked very, very hard’

My twin brother and I were the last of seven children, so we had a very large family. My father was born in Italy and my mother was born in Montreal of Italian parents. My mother was determined not to marry an Italian, because she’d grown up in an English-speaking environment in New Brunswick, but fortunately, when she met my father, that prejudice fell away. We were a working-class family. My father worked for 44 years in a factory making women’s hats, and on the weekends and in the evenings, he drove a taxi. My mother ran a nursing home. So, they worked very, very hard, and by the time I was growing up, we lived in a comfortable, middle-class neighbourhood in the west end of Montreal.

I didn’t have many hobbies growing up, although I did collect stamps and coins, to which I often say I owe my interest in world geography. I did a little bit of sports, but I was not a champion athlete. So, even though Rhodes did not want bookworms to be selected as Scholars, I was a bookworm. My parents had sent my twin brother and me to private schools, and in the process, we were able to skip two grades. So, I started university when I was only 15, and I graduated when I was 19.

On applying for the Rhodes Scholarship

I worked very hard at university, following an honours history programme specialising in the French Enlightenment and the French Revolution. My favourite teacher was the chairman of the history department, who was the most inspiring teacher I’ve ever had. The other teacher who was very influential was pioneering African history as a serious subject for the first time in Canadian universities, and I suspect part of my later interest in Africa can be traced back to him.

When it came to the Rhodes Scholarship, I was encouraged by a senior advisor in the college president’s office who had been a Rhodes Scholar, Rudolph Duder (Newfoundland & University 1932). As a young person, I wasn’t conscious of class, but my parents were, and when I was nominated by my university for a Rhodes Scholarship, my mother was very proud, but she said, ‘You know, Robert, those things are not intended for people like us.’ So, when I got the call from the Québec selection committee, I took my mother’s hand and said, ‘I think I’m going to Oxford,’ and I think it shocked her even more than it did me. I’d already won a Woodrow Wilson scholarship to begin a PhD in history at Princeton University, but I chose to take the Rhodes Scholarship.

‘Oxford changed me’

Oxford changed me, in the sense that I opened up and became more balanced in my approach to life. I date large aspects of my personality to my years in Oxford, my breadth of perspective, and even the importance of exercise, because it was at Oxford that I started doing serious exercise, like squash and rowing. Ever since, I’ve been very intent on keeping that balance in my life, and all of that has kept me healthy and alert.

Everything at Oxford was unexpected, and what impressed me most was the level of personal independence we were given. You could really spread your wings. Some of my fondest memories of Oxford, intellectually, are of lectures: A.J.P. Taylor delivering magisterial lectures with almost no notes except two or three index cards; or the linguist Noam Chomsky, whom I admired deeply as a radical young student.

Because I’d graduated so early, I was younger than most of my Rhodes Scholar class, but being at Oxford was a confidence builder and meeting other Scholars was so enriching. My next-door neighbour in college was Richard Jacobs (British Caribbean & St Peter’s 1968). He would take his shirt off and show me the scars of bayonet wounds he’d sustained when leading student demonstrations at the University of Jamaica. He also kept teasing me about how only he and the African American Scholar from Massachusetts that year really deserved the Rhodes money, because it had been earned through the sweat of African labour. And then, he would break out laughing, because unlike people 50 years later who would use the same argument, he knew it was a bit of a tall case to make. I made friends with other students from the Caribbean too and we would walk around Oxford together. I remember once being on the street and a police car slowing down and expecting some kind of trouble because there were these four black people on the sidewalk. As soon as I popped into view, they sped away. That was the year that the Conservative politician Enoch Powell was warning of ‘rivers of blood’ if the UK continued to accept large numbers of immigrants from the old empire. So, in that sense too, my experience in Oxford was quite broadening.

On a non-linear career path, full of opportunity and some luck

I’d originally planned to become a university teacher in history, but I wasn’t qualified to do that straight after leaving Oxford. So, I decided to do an MA in African Studies at the University of Sussex. I planned to go to Africa to work, but then I was offered a job in the Canadian Department of Finance, as an economist. I moved over to work with the Canadian International Development Agency, for which I was posted to Tanzania, and then I went to Paris to work for the OECD. All of it was a kind of accident, because I’d done economics at Oxford. I certainly hadn’t wanted to work for the World Bank. Like a lot of young progressives, I blamed the US and the World Bank for the death of Salvador Allende in Chile.

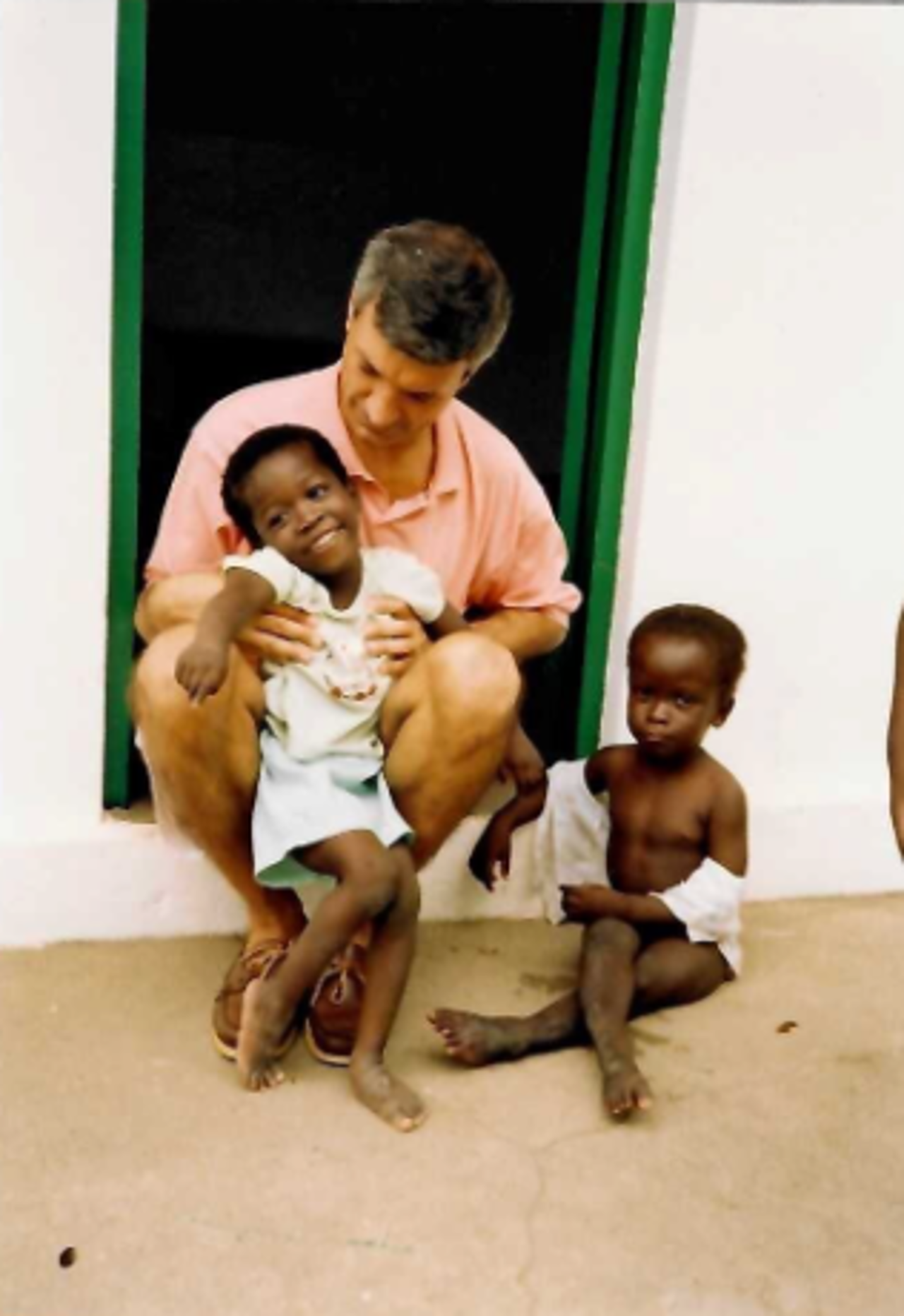

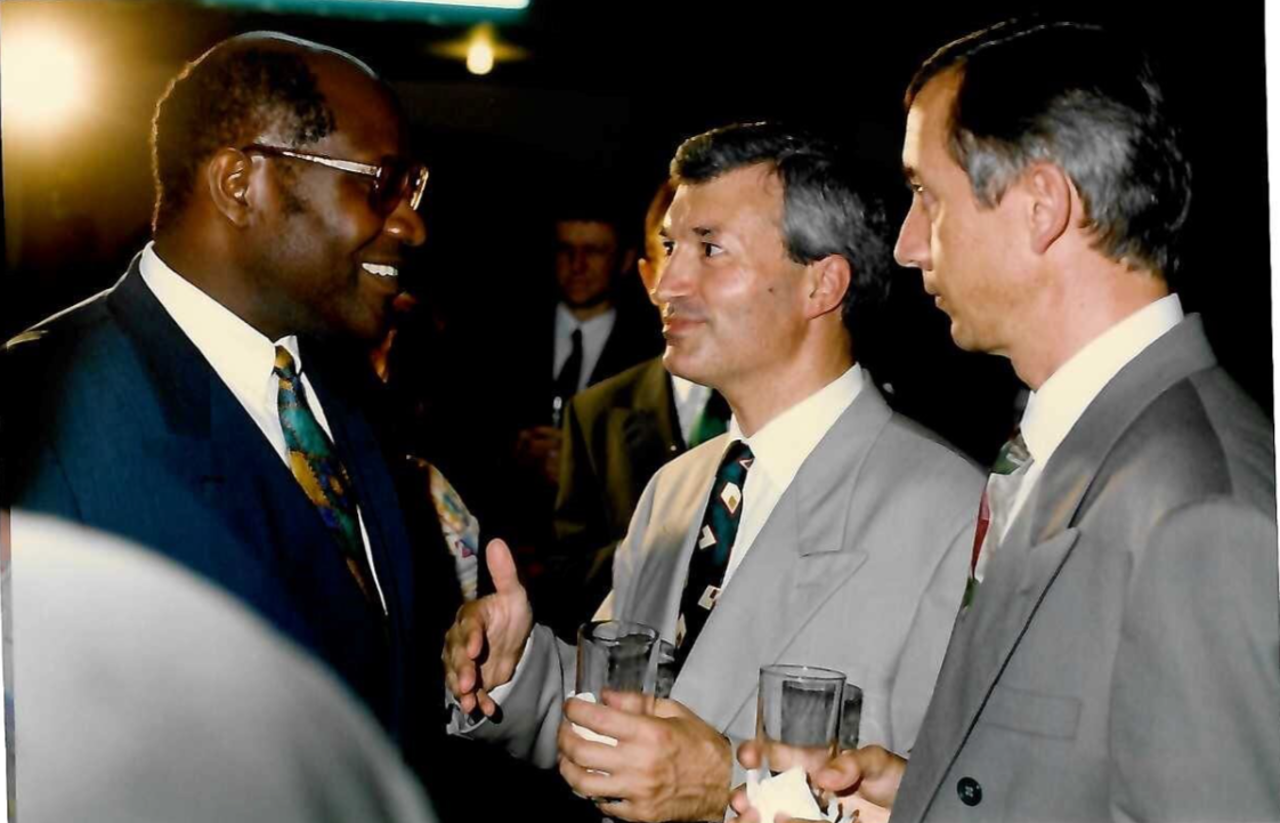

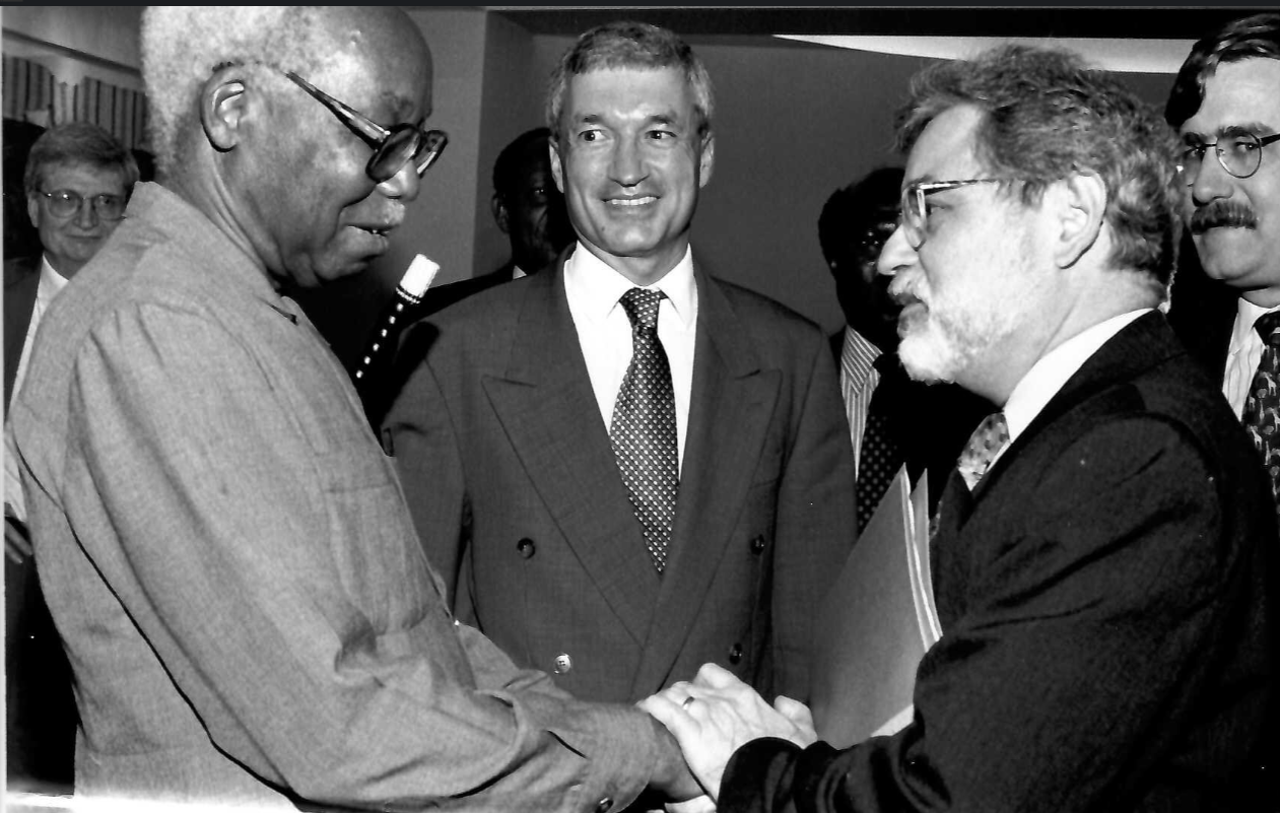

Then, when I was working in Tanzania, I got to know a lot of the staff of the World Bank. They were brilliant, dedicated and idealistic, and I developed a new understanding of the bank and what it might do. I went to work there, and I also went back to living in Africa, this time in the Côte d’Ivoire. I spent much of my time there doing public speaking. In fact, the first talk I gave in Côte d’Ivoire in 1992 was about AIDS, and people were perplexed: ‘Why is the World Bank representative talking about AIDS?’ I drew from personal experience, because I had lost friends to AIDS and had worked as a night volunteer at an AIDS hospice in Washington, DC. I said, bluntly, ‘I’ve only been here six months, so I don’t know very much, but I think HIV/AIDS is going to be one of the two or three most important issues you’ll face in the next 25 years, and I haven’t even decided yet what the others will be.”

‘Fight prejudice in all its forms’

I’ve been a public servant all my life, and as a writer, I feel it’s also a public service, if you write about the right subjects. I see my books as promoting international understanding and overcoming prejudice and superficial opinion. After retiring from the World Bank, my first book – about why foreign aid had failed in Africa and how we could help the continent differently – attracted a lot of attention. The Economist magazine chose it as one of the best books of the year. After that, Yale University Press commissioned a book from me about the role of the Catholic Church in international development. After that, I chose to write about Rhodes, because I was exasperated by the simplistic nature of the criticism levelled at him. I spent two and a half years at the New York Public Library, going through all the original memoirs and biographies and telling both sides of the story in fresh terms, his virtues as well as his faults. People told me I was defending Rhodes, but I wasn’t. I was defending the complexity of history and the complexity of the human character. We need to fight prejudice in all its forms, including coming too quickly to opinions about subjects. Always do your homework.

On telling stories that uplift and inspire

I like reminding myself and others that most human beings don’t even have time to form a political opinion. They are so busy looking after their families and scraping by and yet, many of these people also manage to find time and inspiration to serve the community beyond their families. So, it’s stories like that that I’m interested in finding more of. I like telling stories that uplift and inspire us, about our foibles but also our heroism. I am writing a book about 20 outstanding African figures that most people have not heard about, most of whom are still alive, and not only politicians, but writers, musicians, judges, international civil servants, women football players, and so on, and I’m having great fun with that.