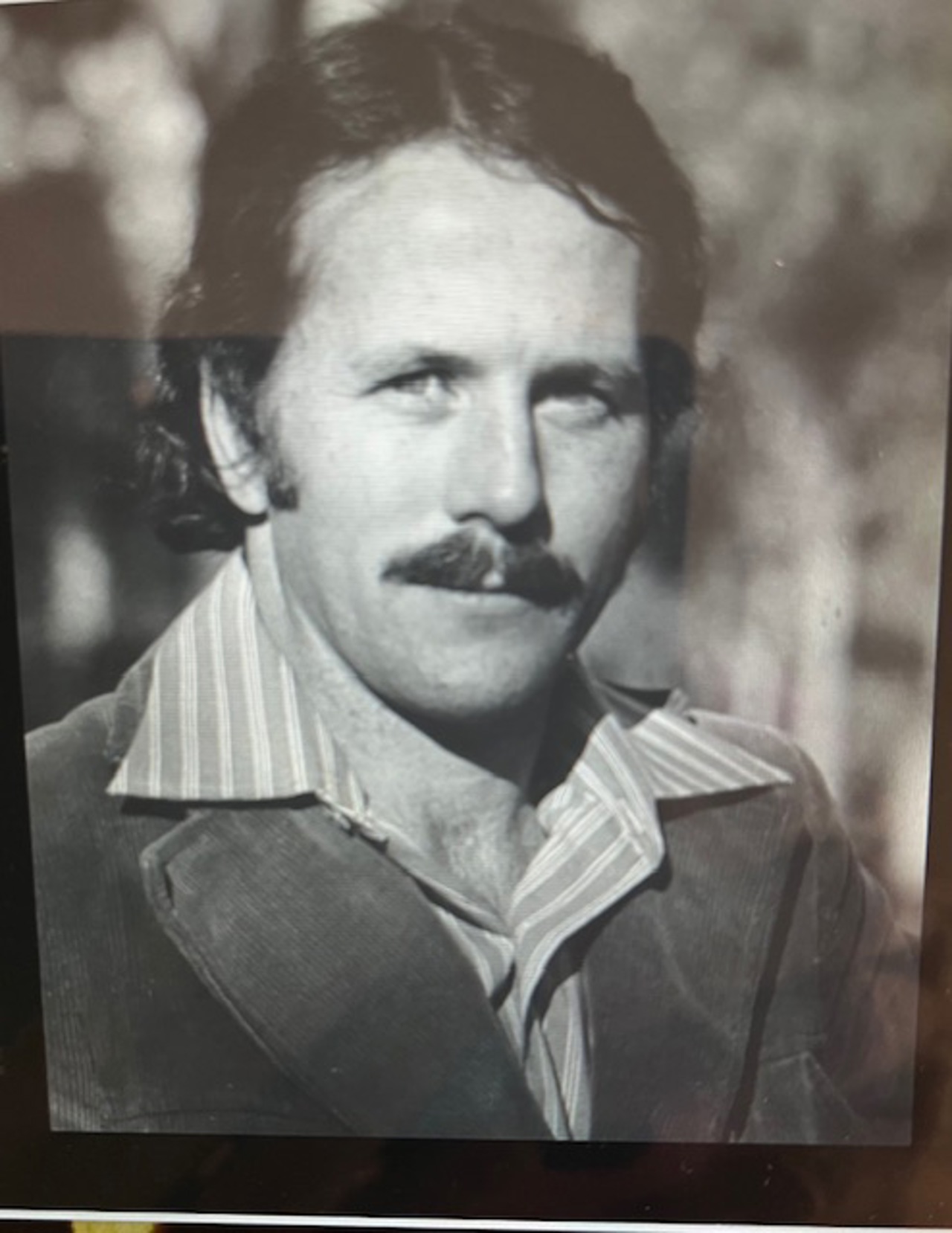

Born in Brisbane, Peter Hempenstall studied at the University of Queensland and in Germany before going to Oxford to read for a DPhil in imperial history. He returned to Australia and took up an academic post at the University of Newcastle, specialising in the history of colonial empires in the Pacific. He is the author of books including Pacific Islanders under German Rule and Truth’s Fool, about the anthropologist Derek Freeman. In 1998, Hempenstall moved to New Zealand to take up the chair of history at the University of Canterbury in Christchurch. Now Emeritus Professor at the University of Canterbury, he has returned to Australia where he lives on the Gold Coast and continues to write history and biography. This narrative is excerpted from an interview with the Rhodes Trust on 14 November 2024.

Peter Hempenstall

Queensland & Magdalen 1970

‘A pretty idyllic childhood’

My great grandparents migrated from Ireland and from Manchester and they grew up in Central Queensland, in a mining community called Mount Morgan and then in the town of Rockhampton. But my father, who became a lawyer, moved to Brisbane in the 1930s. He started a practice there and married my mother and they had five children. Unfortunately, she died in 1956 when I was nine. My father remarried and brought another three children into the family and he and his wife had another child on top of that, so, we ended up with a family of nine children.

It was a pretty idyllic childhood. Brisbane was really a big country town in those days. Children were allowed to roam free as long as they came home when it got dark, and nobody really worried about them too much. I grew up in a strong Irish Catholic family and even though the Church didn’t dominate our lives, it was certainly important in our social life and our education. I went to a Christian Brothers Catholic boys’ school where the education there was broad and basic but not terribly sophisticated. We were taught by a band of very dedicated men, and in my time, there was no hint of the sexual abuse scandals that were uncovered later in some of these kinds of schools, but there was a certain sadism in that corporal punishment was a big feature. I didn’t experience too much of that because I was a bit of a nerd and happy to be so. I also did a lot of long-distance running as a child, and later, I started played rugby.

On applying for the Rhodes Scholarship

At school, the aspirations for us were, at most, to go to teachers’ college or perhaps to join the Queensland or the Commonwealth Public Service. I didn’t really know what I wanted to do and, being from a fairly religiously observant family, I was quite attracted to being a teacher with the Christian Brothers. I spent two years with them as a novice and that was the beginning of my tertiary education, meeting people who taught me the power of reading and the power of ideas. But although I could handle, I thought, the vows of poverty and chastity which we were required to take, I could not handle the vow of obedience, so at the end of two years, I decided this was not a life for me.

I came home to Queensland and went to university to do an arts degree. This was the time of the Vietnam War and as well students in Queensland were getting involved in demonstrations in support of civil liberties, particularly the right to march down Brisbane streets in support of issues around the war. I didn’t actually become an upfront activist, but I found my own voice, came out of my shell a little and took part in those marches and demonstrations. University is also where I first began to be interested in the world of ideas and learn how to do ‘history’. I hadn’t done any modern history at school but learned from some wonderful teachers at the university. In those days, you still had to have a foreign language to get an arts degree, and I decided to study German. I had a wonderful Lebanese Australian teacher, John Moses, who persuaded me to put my German together with my history training so that I could work on German history. He helped me get a postgraduate scholarship to study in Germany.

But then, the Rhodes Scholarship was dangled in front of my eyes. It was my professor of history, Gordon Greenwood, who persuaded me to put in for it. By that time, I had a job lined up, to train as a diplomat as well as the postgraduate scholarship in Germany. The day of the interview for the Rhodes was the day before my final honours history exam, so I remember just sitting with all the other candidates frantically reading my exam notes. I think I was as gobsmacked and as surprised as anyone else when I was called in to meet the panel and congratulated as the Rhodes Scholar for Queensland for 1970.

‘You could learn a lot about other cultures’

I spent a year in Germany before going to Oxford, and that was the making of me, in that I grew up and met wonderful friends and had the chance to travel. Going to England was, in a curious way, almost a step back. It seemed to me far less modern and prosperous then Germany. But then, of course, I made my way to Oxford, and it took me into its bosom and things changed from that point on. I began to gravitate towards the study of Pacific and imperial history and Oxford was the perfect place for me to do that. The Rhodes Trust was extraordinarily generous in funding me on further research trips back to Germany. I spent several months in Potsdam in the former East Germany, working my way through the German colonial archives on Germany’s Pacific colonies, which nobody had touched at that point.

I came back to Oxford and sat in Magdalen’s medieval history library and literally wrote in pen my DPhil, because I didn’t even have a typewriter. My wife was with me by that point, because we had married at the end of my first year as a Scholar. She was the one who could type, and she did everything. She was wonderful. After we got married, we moved up to Summertown and made a lot of friends there. I think what was unexpected for me, and very welcome, was how multinational Oxford was. If you took the trouble and the time, you could learn a lot of about other cultures, and I think, I hope, I did that.

‘I was finally coming home to the Pacific’

If you’re a Rhodes Scholar, you’re often offered opportunities you wouldn’t have had if you weren’t a Rhodes Scholar. I got my first job offer back in Australia because I was a Rhodes Scholar, not because I could actually do the job they wanted. Luckily, I was able to persuade them to let me teach the things I did know about. It’s a terribly snobbish thing to say, but back then Newcastle University in Australia was not people’s first port of call when they thought of an academic career. It was a young, redbrick university in a very industrial, working-class town. I had thought it would be just a stepping stone to somewhere else, but I ended up spending 23 very happy years there, teaching the sons and daughters of miners and working class people who were trying to climb into the middle class. It was a highly political education and a cultural education for me too.

I moved to New Zealand in 1998 when I was offered the Chair of history at the University of Canterbury in Christchurch. Those were very happy years too, because I was finally coming home to the Pacific. I had had the chance to travel in the Pacific some time before that, and I fell in love with it. In New Zealand, I was able to go and do more research in Samoa and in Hawaii. Intellectually, New Zealand was really humming in ways that I didn’t find when I was in Australia. As an historian I also started to move into the writing of biography and discovered just how much I loved the process of writing itself and the way the lives of historical personalities were constructed. I have since written four biographies.

Now, I live in Australia again, and my focus is very much family. It’s lovely to be closer to my children and to my brothers and sisters and to be able to see them more regularly. I do some volunteering, working with a cycling group that runs trishaws in local parks for people in disability care and aged care homes and I sing in a choir. I read a lot, and I’m still writing. It’s an extraordinarily privileged life and I’m very grateful, especially for the opportunities that began with the Rhodes Scholarship way back in 1970.

‘More power to it’

I do think it’s important not to see the Rhodes Scholarship as the culmination of what you’ve done. It’s the beginning of something, an opportunity which is always present. You’re part a gigantic family that never deserts you. And Rhodes House and the Warden do a marvellous job in keeping us together as a family in the present, so that even though I got my Scholarship 50-odd years ago, I still feel as though I’m very much part of the Rhodes family.

That kind of opportunity brings enormous responsibilities to serve. I think the Rhodes Trust is doing a superb job at the moment setting young Rhodes Scholars up to continue that tradition of service. It may not be what Cecil Rhodes would always have recognised, but more power to it. At the centre of the Rhodes, it’s about being grateful, being humble and carrying it forward for others.

Pacific Historian Manqué

This chapter first appeared in Lal, B. and Munro, D. 2024. Serendipity: Experience of Pacific Historians. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press.

PACIFIC HISTORIAN MANQUÉ

Serendipity is a good word when you are trying to get a handle on how you got to where you are today. Not its ‘happy accident’ meaning exactly. That smacks to me of a certain false modesty. But I can relate to being in a particular place at a time when the range of opportunities for personal career choice(s) was infinitely greater and more easily grasped, almost without effort, than for young people today. And I have become a great believer in that iron law of History, ‘the Law of Unintended Consequences’ when it comes to personal choices, and it strikes me as a workable meaning for ‘serendipity’. Let me explain by tracing my path to a career that might have been but is not quite. But beware: constructing a life narrative from remnant memories is always a fraught project full of artifice. This is one story among many that might be written.

Though I grew up practically beside the Pacific Ocean in south-east Queensland and spent much of a not-very-dissolute youth loafing on beaches, I never had a fatal attraction to the islands. Nothing from my school days prepared me either, for I did not study modern history at school (‘ancient history’ yes, from a dog-eared copy of J.H Breasted’s Ancient Times: A History of the Early World. It fired me briefly with the fantasy of becoming an archaeologist in Howard Carter’s footsteps). The Pacific education of young Peter began in 1963 when I won a prize to fly in an ancient Canberra bomber to Mackay in north Queensland. That’s a story for another place, but I remember encountering for the first time descendants of Pacific Islanders living in and around Mackay, in my Queensland, shadows from a history I knew absolutely nothing about. I could pretend to you that was a serendipitous moment but in truth the experience never triggered anything very deep in me. But the next encounter did.

In 1966, at the end of my first year at university, I went on a working holiday to the Territory of Papua New Guinea where, like thousands of Australians, members of my family were making good money and could hand me on from district to district to see the sights. My travel diary of that six weeks is full of extraordinary, crude naïvetés. I hadn’t expected to see ‘natives’ driving big, modern trucks. I wasn’t prepared for the smell of sweat-laden bodies, or the sheer exuberance and colour of local life and art. The sight of so many Chinese was a surprise, the beginning of a dim apprehension that the Pacific was not a monochrome place at all. The magnificence of the corded mountain ranges over which I flew to get into Highland valleys opened that crack a little wider, as did snow on Mount Wilhelm and the warmth of the soil as I climbed the sides of Rabaul’s volcanoes. It was no Damascus Road, but I came away from Papua New Guinea with some pomposities punctured, uneasy at the master race culture in which I had taken part – the use of local women and men as domestic servants; getting a job because I was white and entitled; unloading ships at Lae wharf by sitting in the shade checking the manifest while men old enough to be my father stacked cargo.

A university education in the 1960s was a very privileged thing. It operated as an asset mainly for the middle professional classes to reproduce themselves, with the help of scholarships and living allowances from government. The logical path for me was the Law, following in my father’s footsteps. Generously he never put pressure on me to do so and I could feel no affinity with the culture surrounding his practice. To be honest I had only the vaguest notion of what I wanted to do with my life. Perhaps school teaching, and I edged myself in that direction by doing an Arts degree – history, German language, English literature and anthropology. Why that combination I cannot say. Probably a sense of what I would be best at if I were to teach, and the vagaries of timetabling. I was not yet won for history, and I think I chose anthropology because it seemed a distant cousin of my fantasy career as an archaeologist. It certainly had unintended consequences, German language even more so.

At that point in the mid-1960s, the University of Queensland was the last remaining Australian university to require the study of a foreign language as part of an Arts degree. I had Latin from school days but, though I could quote sections from Virgil’s The Aenid, the thought of taking it on at university bored me. But the modern language departments all offered shrewdly organized sequences of courses designed to introduce the language to newcomers like me and bring one up to matriculation standard in one year. If you then went onto study that language for a further two years, the early introductory courses would count towards your degree. I could have chosen French but the German department was pushing German as a niche subject for school teaching. It had a mystery and a strength about it that appealed to my ignorance (like most Australians I knew German culture only through the stereotypes in war movies). Besides, friends were taking German and the department was very friendly and generous with social events!

Anthropology had Peter Lawrence of Road Belong Cargo fame. The book had just come out and I devoured it as much for its literary quality as its masterly story-telling and cultural insight. It is a book I have refused to be parted from, though I have dispersed most of my library offshore. Lawrence was a dynamic teacher and raconteur, even as he explained segmentary lineages and various principles of the discipline.

History at UQ in the 1960s was expanding its offerings to cover East Asia, South-East Asia and Indonesia, though not the Pacific. Australian history was taught by Roger Joyce, the biographer of William McGregor of British New Guinea; he introduced us tangentially to Papuan history. Any sense of a history of indigenous people of Australia was still some years away. Charles Rowley’s volumes on the destruction of Aboriginal society were in the process of being written, and Henry Reynolds book on Aboriginal resistance to European settlers, The Other Side of the Frontier, did not come out until 1981, three years after my first book on Pacific Islander resistance: another fantasy on my part, that he was following my footsteps. Australian history was largely its convict beginnings and the various political developments. But in the hands of Joyce and Denis Murphy, Sheridan Gilley and George Shaw, it introduced me to a world of politics, cultural institutions and ideas that both shamed my ignorance and enlightened me about the possible depths for study and interpretation. But the course that caught my imagination as a way to see into the world and its cultures was the very first course I took in modern history: ‘British History, 1485-1815’, taught by Christopher Falkus. Falkus, who sadly left academic life soon after to become a publisher in England (he was himself English), made Tudor and Stuart England come alive in ways that captivated his classes. He and his colleagues introduced us to Geoffrey Elton, Christopher Hill, J.H Plumb and Eric Hobsbawm, to Thomas More’s Utopia, to the murderous, sexual, power-hungry lives of generations of English rulers and to the cultural institutions that upheld them – all in a peripatetic, arm-waving, theatrical set of performances that was the best teacher training exercise I could ask for.

I discovered that I was rather good at this thing called modern history (so different from the rote learning of ancient stuff we had studied at school). We learned to parse original documents, explore multiple interpretations of the same events, internalize the rigours of sourcing and referencing, and, in a continuing flow of papers we wrote over the length of full year courses, to venture however timidly our own interpretations (‘constructing your narrative’ was not yet in vogue). At the end of first year I had to toss up whether to go down the road of specializing in anthropology or history. I chose history because the historians encouraged me and the anthropologists didn’t. Meanwhile my German ticked along under a succession of strong teachers with bow ties and very precise accents.

The law of unintended consequences now came into play. A parallel stream of honours courses of four years duration in each discipline was the gold standard for entry to post-graduate work, indeed even for the best career opportunities in private enterprise or public service. One could begin the honours stream in first year, but normally the ‘best’ students were ‘courted’ to enter in second year, where, besides a series of smaller seminar courses in thematic or regional histories, the emphasis lay in document analysis and interpretation, exhaustive essay writing, a mini dissertation in third year and a larger one in fourth year. Along the way, in debates about theory and method (I still gag at the thought of Dray and Gardiner and ‘covering laws’), one was supposed to pick up what History was all about.

I had done well enough to come to the attention of John Moses, a young lecturer of Australian Lebanese descent who had been trained in West Germany under the great Reformation historian, Walter Peter Fuchs. I studied European history with Moses and discovered the Fischer thesis and the heated German debates about the origins of the First World War (getting a re-run these days in a way that makes John Moses angry, because of an attitude that virtually absolves Germany of responsibility for the war’s outbreak). He was also just beginning to dabble in microfilm records from the German Colonial Archive in Potsdam, East Germany. Moses was drawn to the Governor of the German colony of Samoa before 1914, Wilhelm Solf, who later became the Kaiser’s Minister for Colonies and helped preside over the obsequies of the Kaiserreich; Moses would write about Solf for Pacific historians and push him in my direction. But not quite yet.

However, alert to my studying German he proposed I pitch my Honours dissertations in a direction that would exploit my knowledge of the language. Moses even suggested he might be able to advocate for a postgraduate scholarship for me to study in West Germany. Who was I to disagree? This was heady stuff. The decision to study German had led, completely without my intending it, to a set of horizons beyond anything I could imagine when I began university. For my third-year thesis I chose to examine Lord Acton’s famous writings on freedom and his struggle with the Catholic church over the push for the doctrine of papal infallibility. Acton of course had German antecedents and an important teacher and mentor in Johann Ignaz von Döllinger, the German theologian and church historian, and German sources helped to throw a light on the development of Acton’s ideas. That little piece of analysis, combined with what John Moses illuminated about Germany’s perilous history sparked an interest in how ideas in the hands of powerful individuals could move ever so slightly whole social and religious environments.

The Pacific was still nowhere to be seen in the courses I was taking. Nor was it on my radar. But for my final Honours thesis John Moses loaned me his stash of microfilms on German companies trading in the Pacific as Bismarck was uniting the German states into one Reich and beginning to build a colonial empire. To begin with they were simply a tool to get through the thesis requirement. But again all unintended, they introduced me to the history of European contact with a myriad Pacific islands and their inhabitants, particularly Samoa and Tonga. I discovered Keesing, Davidson and Gilson on Samoa; Rutherford on Tonga, storyteller historians and social scientists with a bent for biographical portraits and context driven narratives of social and economic development. My anthropology studies, without intending it, began to bear fruit in an appreciation of the subtleties of title competition, ancestral lineage histories and the rituals of encounter with European strangers. The Germans suddenly emerged as major economic and political players. They possessed a large and, to me, hitherto invisible literature on nineteenth century Pacific contacts, on travel and trade, and through Augustin Krämer, extensive studies of custom and social structure.

I won’t claim I became a ‘Pacific historian’ at that point – the complexities of Germany’s history intrigued me more – but with John Moses’ coaxing I went off to Canberra to seek more sources from what I was told was the mothership of emerging Pacific studies – the Department of Pacific History at the Australian National University (ANU). With no expectations and a parochial attitude to a discipline that I still saw mainly as a tool to get me a job, I was suddenly drawn into a fellowship of scholars who treated me as a budding apprentice. Niel Gunson, Bob Langdon, Harry Maude, Deryck Scarr and Peter Corris lavished advice upon me, opening the filing cabinets of the Department’s ‘Records Room’ to search for whatever I wanted. The head of this seeming family, James Wightman Davidson, was not in Canberra at the time and I never did get to meet him before he died in 1973. But I left Canberra with a niggling sense that this Pacific history, or the study of cultural encounters and the struggle over ideas between Pacific Islanders and European traders, missionaries and colonial officials could sustain a world of scholarship on its own. And this evangelistic family of scholars seemed to expect me to join with them in their grand mission to remake the way the history of imperial activities and cultural encounters was told.

But the world held many oysters for a male baby boomer (technically I was a ‘victory’ baby, born nine months after the end of World War II). The late 1960s was an extraordinary time of opportunities, proffered by public and private employers who literally set up job markets in the courts of universities to entice fresh graduates onto their books. Queensland was no different. These were highly gendered opportunities of course, the spoils flowing mainly to males; second wave feminism was just beginning to enter my consciousness. I had job offers and training opportunities thrust at me in my final Honours year, 1969, including a cadetship in the Department of External Affairs. On top of that my academic marks resulted in not one but two overseas postgraduate scholarships, one to Germany thanks to John Moses’ good offices and one to study at Oxford. It was flattering and revelatory for someone who had simply set out to be a schoolteacher and lacked a sense of self-confidence in intellectual environments. That emerging sense of self is one of the many stories that belong to a different quarter of my life.

Yet with the arrogance of youth I saw no reason why I could not have it all – study now and worry about job prospects later. Deferring any decisions about what ultimately to do with my life, I and my scholarships set off for Europe. I arrived a colonial Queenslander with a battery of empirical skills and an urge to write, but still an inchoate sense of what one did when one did History. Germany began the testing of all my learned assumptions, as well as conspiring to make me an adult. The first humiliation occurred when I landed in an icy, snow bound Hamburg: after three years studying the language, I could not understand the first person who spoke to me (a German customs officer asking whether I had anything to declare). Then there was the matter of fitting into an alien culture – good practice for a Pacific historian-in-training, even if I did not see it at the time – and by walking its cities learning the deep history of a Europe still scarred from the war. There was also the not inconsiderable task of deciphering the traditional gothic writing script of the records I was exploring in the Hamburg Staatsarchiv. That took weeks and months with a medieval language primer by my side.

Studying German historiography at its source alerted me to its formal standards of argument and language. To me it smacked more of a social science than the literary tradition I had imbibed at home; die Geschichtswissenschaften were formidably grounded in empirical research and endless referencing. German history in the 1970s provoked incendiary arguments across the nation, not only about the first world war but about the disaster of the second. The ideological roots of National Socialism, the philosophical underpinnings of the nation’s alleged special path that led to it (Germany’s Sonderweg) were debated openly and fiercely in newspapers as well as journals. But there were huge silences across the literature about Germany’s colonial history, dismissed as a mere bagatelle by most scholars. That meant the archives that had survived the war were rich in untouched files on Africa, the Pacific and East Asia from the colonial administrations, the German navy and the Foreign Office. Peppered all over West and East Germany were also museum collections and their archives and the records of missionary churches active in the colonies, some guarded closely, most simply locked away and never used. For a tentative student looking for a PhD topic, it was difficult to know where to begin.

My stay in Hamburg persuaded me that following the money in a study of trading companies and their colonial connections was not for me, even with records substantial and open. Economic history never captured my interest or imagination, though at this end of my life I grieve its erosion as a disciplinary force and believe its return to the centre of History’s attention is a major priority. It took Oxford and a group of historians of imperialism to crystallize what I was doing in Europe. I fell under the supervision of Colin Newbury, a New Zealander who had gained the first PhD in Pacific history from the ANU. That was a truly serendipitous relationship that linked Oxford to Canberra to New Zealand and on to the islands. The link travelled through Africa. Newbury had taught in West Africa and was now engaged in African studies with groups of South Africans, Zimbabweans and Kenyans through the Institute of Commonwealth Studies. His own research was on West African protest and he introduced us to the generation of colonial resistance scholars in England and the USA – Terence Ranger, John Iliffe, Ali Mazrui, Robert Rotberg. That sowed the seeds of studying colonial resistance movements utilizing the German archives. But the Oxford team always emphasized a wider context: the need to understand how empires worked, the material power they deployed, the structures of rule they established and the strategies used to counter, defuse or manipulate indigenous and settler resistance.

Much criticism has been heaped on ‘old fashioned’ imperialism studies by post-colonial scholars. They see too much orientalist naivete in the use of compromised sources and a perhaps unconscious complicity with the negative, exploitative policies of colonial regimes. Oxford in the 1960s and 1970s did exhibit a certain tweed-coated emphasis on ruling elites. I in turn exhibited what I have called elsewhere ‘a certain subaltern response on my part to the whole Oxford tradition…If they were interested in metropolitan, imperial factors, I was for the fortunes and strategies of those who, like me, felt colonised and intimidated by the imperial mentality.’ That says more about my feelings of insecurity at the time than the failings of Oxford dons. For the likes of Ronald Robinson, John Gallagher, Freddie Madden and David Fieldhouse taught me valuable lessons about exploiting foreign language archives, comparing colonial histories within a common imperial experience and learning about the culture of the metropole as well as the cultural histories of colonized peoples. All unintended again, Oxford’s Institute of Anthropology under Maurice Freedman, with Evans Pritchard still a presence, helped in that regard, keeping me grounded in cautious thoughts about indigenous cultures.

It was a paradox that Oxford should pitch me into the Pacific. Under the guns of Russian soldiers in Potsdam, East Germany, banished from the cafeteria of the Zentralarchiv because I was a suspect visitor from across the wall, I acquired a secret knowledge of the Pacific colonies through German eyes. I found it doubly ironic that I was allowed in because I was studying resistance to colonial rule when outside in the streets any hint of resistance was being crushed by the Stasi and soldiers of the Soviet Union. East German historians were concentrating on anti-colonial tracts about German atrocities in Africa. The few who were in the archives gave me curious stares as they went off to lunch with their compatriots, leaving me alone on a corridor bench with my sandwiches. No other German historian from the West had studied these records of the German administrations in Samoa, New Guinea and Micronesia. But remarkably, two compatriots from the antipodes had their signatures inscribed in the visitors’ book before me – Marjorie Jacobs from Sydney University, who had managed to arrange some microfilming in the 1950s; and Stewart Firth, my contemporary at Oxford who was studying German colonial labour policies. Stewart in a typically generous gesture bequeathed me his neatly organized piles of early photocopies of the Potsdam records that he carried around West Germany in a little box trailer behind a Morris Minor. We both luxuriated in archival treasures that were little used and even less known – a quasi-archaeological deposit that, again all unintended, fulfilled my early career dreams. Within the lavish sets of bureaucratic and travel reports, telegrams and cultural observations, letters in Samoan came swimming to the surface. How could one become a Pacific historian without learning at least one Pacific language?

Though I was 20,000 kilometres away, the Pacific also entered into my imagination through pilgrimages in West Germany to one Christian missionary society after another. Evangelical Protestant families and Catholic priests, nuns and brothers lived among Pacific Islanders, some stubbornly righteous in their religious conviction, some studious observers of local beliefs and rituals. All of them were in the islands for the long haul, unlike the colonial rulers I was reading. The Pacific came alive in condescending or agonized portrayals of Pacific Islanders and their ways of life. How easily vehement proselytizing and self-doubt rode side by side was a valuable historical and personal lesson. The Germanies were also full of the most beautiful, often sacred Pacific artefacts in museums and monasteries. They had been bought or pilfered during ‘ethnographic expeditions’ under the Germans and often secreted away in vaults lest newly independent Pacific peoples wanted them back. An education in History turned out to be an education in international museum politics as time went on.

I recognize now that, without query on my part, I was following the tried and tested route of Anglo-Australian students back to the imperial centre by going to Oxford for postgraduate studies rather than staying in Germany or going to the United States. I could not have done any of it without the help of my then wife, Jill, who gave up her job to accompany me around the various archives in West Germany. Jill was research assistant, amanuensis and forager, partner in overcoming the inevitable cultural misunderstandings, and producer of the thesis that finally emerged from my written drafts. Despite the revelations about Pacific cultures and histories I absorbed, Europe and Oxford were supposed to be another leg in my search for a career that was not about academic History-making. We had always intended to return home (another retreat to my comfort zone). But the early 1970s were the years of oil-price shock. Jobs were disappearing at home. Australia was in economic and political turmoil. When the ANU offered me a postdoctoral fellowship in the Department of Pacific History it seemed a perfect means to maintain my holding pattern while looking around.

It was that year, 1974, that finally persuaded me that perhaps a research and teaching career was what all this preparation was for. They were the last years of ANU’s extraordinary generosity, some would say profligacy, in funding extensive fieldwork in the Pacific and Asia for its research students and staff. I visited all the sites of my doctoral arguments. They included the village and grave of the clever opponent of the Germans in Samoa, Lauaki Namulau’ulu Mamoe on Savai’i, and the steep cliffs of Sokehs district in Pohnpei in Micronesia where Sokehs warriors, led by Soumadau en Sokehs, attempted to hold at bay the marines of the German navy and their local allies. I drank kava and sakau, smoked a little pot, caught dengue fever. I encountered open-handed hospitality, deep internalized Christian faith, wariness about my questions, a depth of genealogical memory whose authenticity I had doubted. I experienced the rigours of tropical living, confusion in interpreting encounters in high places and low, liberations and binding limits in friendships. I came away with a sense of abiding mystery about the Pacific which my dalliance with the records of Germans who themselves were mystified was never going to clear up.

No matter. Was I now a Pacific historian? I thought I was getting close and my first ‘real job’ allowed me to tinker on its edges, teaching at the University of Newcastle north of Sydney. Newcastle was intended as another way station but in fact became the family home where our children grew up. At least it was on the Pacific. And this very traditional red brick academy enabled a career teaching about the Pacific islands and its colonial settler neighbours, Australia and New Zealand. Two big figures from Canberra’s fertile training ground, Noel Rutherford and Alan Ward, taught and wrote alongside, with a varied cast of local Islanders and Maori adding indigenous voices and ritual.

But Newcastle with its rich convict and working-class industrial history opened new vistas, forced upon one as the national university system was redefined, student numbers fell and rose, staff came and went. I was pushed into Australian and local histories and discovered a resister of another stripe – Ernest Burgmann, forest axeman from the Manning district who became radical priest, Anglican Bishop of Canberra & Goulburn and the scourge of a conservative church and civilian government. Looking back, I see now that I was drawn to a string of outsiders like Burgmann, Lauaki in German Samoa and the rebel leader on Pohnpei, Soumadau en Sokehs – like me existing on what I regarded as the fringes of my chosen subject area; a form of self-definition perhaps. It was also becoming clear to me that cracking open the life history of someone whose cultural history I shared was a touch more comfortable than wrestling with shadowy Pacific Island figures.

Biography has been a much maligned form of practice within History’s self-justifying boundaries – a form of ‘History-lite’ to some critics. But its methods in the hands of historians are the tried and tested methods of historians everywhere, and the best biographies interweave historical context with a narrative fluidity that is comfortably within the historian’s range. Good biography does continually throw up discomforting questions for historians, questions of theory around personality, the identity of the self and the psychological transference between the subject and the biographer. These are forbidding obstacles as is the ultimate question whether one can ever accurately read another’s inner life. But as the Canadian historian P.B. Waite has remarked, biography is one instance of the way history happens and it has allowed me an anthropological focus on the rituals of self-making as well as the cultural frames in which that occurs. That led to another unintended bonus: while beginning the research for a full-blown biography of Wilhelm Solf, I met Paula Mochida, educationist and librarian professor at the University of Hawaii. She too was working on Solf. Why not combine our efforts? It led to an experimental joint biography. Our quest for a hard-edged empirical life-line converged with all those theoretical questions in a series of ‘conversations’ between chapters that showcased both our thinking and the artifice of building the narrative of a life.

Encounters in the Pacific with Pacific peoples have made me increasingly wary of attempting to cross that biographical beach into the realms of the Pacific Island self. Ten years living in New Zealand, receiving a daily newsfeed about the islands, rubbing shoulders with Pacific peoples and, however misplaced, feeling an inclusiveness with them strengthened a sense of Pacific place in me. Paradoxically the experience also heightened my caution about doing Pacific ‘biography’. Conference encounters and debates about the propriety of pakeha ‘gatekeepers’ writing the lives of Maori gave me pause. I wrestled with anthropology’s attempts to articulate the psychology of Pacific personhood, and, in the end, decided it was not for me, an outsider, to continue travelling down that road where the boundaries between individual, community and ancestors were so intimate and alien.

It was with a sense of relief that I retreated to the edges of the field. I enjoyed sifting ideas, tracing their origins in cultural movements and watching how individuals deployed them in their own chequered lives; shades of that very early work on Lord Acton. Germany’s twisted histories had prepared me for how ideas could cascade outwards and down the generations. New Zealand colleagues, who wrestled every day with whether they were on their own or part of a bigger idea called Australasia, drew me further into examining the movement of ideas across the Tasman.

Then a fleeting ghost from my Samoa past – Derek Freeman, the anthropologist I had avoided for years out of an intellectual fear – paid my mind a visit during his dying days. Or should I say I paid him a visit as a character whose tangled life and ideas would make a fascinating study. It would educate me more deeply about one of the Pacific’s more enduring puzzles, which remains an issue of flaming contention among anthropologists – Freeman’s treatment of Margaret Mead. Accompanied by a simple act of friendship and the laser-like intelligence of another anthropologist, the late Don Tuzin, the project gave me entry to the bowels of a discipline that helps shape our understanding of the Pacific, and of ourselves as social, thinking, competitive human animals. That has come with its own controversies and misreadings. Some anthropologists believe that to try to understand another person in their own terms is to identify with that person, an effrontery to the discipline and a betrayal. That I simply reject.

None of this was intended or plotted on some career spreadsheet. Much of ‘my Pacific’ has little to do with the historical day-to-day living of Pacific Islanders. My writing hasn’t shifted much from how I described it nearly thirty years ago – ‘a kind of post-eclectic second-hand discourse which has provided me with a voice to contribute to the series of conversations that are going on’.

A lot else has gone on around those conversations and outside them. I have helped in the hunt for the original written constitution of Tonga for its centenary in 1975, detecting a roll of brown paper behind a filing cabinet in the Department of Pacific History in Canberra; it turned out to be the constitution. I have, alongside Samoan workers and Kilifoti Etuati, Secretary to Government at the time, very gingerly carried vermin-ridden German colonial documents out of the old gaol cells at Vaiusu that were filled with cases of degrading dynamite. I have, with colleagues, faced a dressing down by native Hawaiian scholars for Pacific history’s treatment of the deep history of their colonization. I have struggled too to learn Samoan among Samoans who gave of their time and patience, and have danced to thank them for their efforts. Dancing and singing have been natural accompaniments of Pacific history conferences, even if our self-conscious western performances have been excruciating to watch.

Cumulatively, these acts of my History-making constitute a sort of citizenship of Pacific history, even if never consciously pursued. The Pacific, with all its corners of research and life, with the colleagues whose work I admire and the friends I have made, has turned out to be bigger than all the intentions I have harboured. I have always considered my work as lying on the boundaries of the field we call ‘Pacific history’, in a sort of frontier zone of histories of individuals and of social communities, some of which have Pacific resonances, some not. The fluid nature of these boundaries themselves interest me more as a I grow elderly. Tessa Morris-Suzuki reminds us that arbitrary forces, often academic-political, determine how frontier lines are defined. I have increasingly become conscious of how this applies to Pacific history, in the vast arc from area studies to postcolonial studies that contains a disparate array of disciplines, targets of knowledge, ways of knowing and genres of communication.

History has for me always been a tough-minded catholic discipline: an exploration of the shards of the past that have come down to historians in many forms. Its goal is to find the meanings people have given to their lives and, in the spirit of the history that Inge Clendinnen wrote, how they lived with the consequences of the choices they made; that has moral value too. Whether anything I have said from the edges of the field makes meaningful sense to others is not for me to judge. If I am lucky, then, as Greg Dening has remarked, someone will do the historiography of the ‘Pacific history’ I have written.

SOURCE ESSAY

The Breasted from which I received my introduction to history (Ancient Times: A History of the Early World. Boston: The Athenaeum Press) was the largely rewritten 1935 edition, which shows how up-to-date my school was in its History library in 1963. But then we did not have a library, except for a couple of volumes of physics and mathematics textbooks that our science teacher paid for out of his own pocket. My copy of Breasted has disappeared, which is sad, for it is worth quite a lot online now, though I suspect the endless underlining I did might rather reduce its value. My copy of Virgil’s The Aenid. London: Vintage Books, several reprints, equally disfigured, has also slipped away. I have also searched high and low for my original copy of Keith Leopold’s Introducing German. Sydney: Angus & Robertson, 1964, which I believe the best and most lucid introduction to a very rules-bound language. It kept me company through several European winters but has left my company along the way.

Among the anthropology works I consumed, Peter Lawrence’s Road Belong Cargo: A Study of the Cargo Movement in the Southern Madang District, New Guinea. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1964, taught me a great deal about how to write an historical narrative (almost a novel in its literary tone and plot-driven form) informed by theoretical concerns. Roger Joyce was primarily a political historian and his biography of MacGregor, which came out after I had left his classes (R.B. Joyce. Sir William MacGregor. Carlton: Melbourne University Press, 1971) is a rather chunky, chewy meal for the lover of extreme detail. Denis Murphy was still a young academic before he became a state Labor politician; Murphy died prematurely. He is best known for his biographies, example: T.J.Ryan, a Political Biography. St Lucia, U of Queensland Press: 1975, which has lately become useful in writing my family’s history.

I read with increasing admiration and understanding all of Charles Rowley’s magisterial works on Australian indigenous societies and their confrontation with settler Australians: The Destruction of Aboriginal Society. 1970; Outcasts in White Australia. 1971; The Remote Aborigines. 1971; and A Matter of Justice.1978, all from Canberra: Australian National University Press. Henry Reynolds’ The Other Side of the Frontier: An Interpretation of the Aboriginal Response to the Invasion and Settlement of Australia. Townsville: James Cook University, 1981 (and pretty much all of his works) became a valued text in the Australian History courses I taught.

The works I most remember from the course Christopher Falkus taught were: Thomas More Utopia: The English Translation thereof by Raphe Robynson. Second Edition, 1556. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1965; Geoffrey Elton. The Tudor Revolution in Government: Administrative Changes in the Reign of Henry VIII. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1953 and his England under the Tudors. London: Methuen, 1955; Christopher Hill’s early post-war works, Puritanism and Revolution: Studies in Interpretation of the English Revolution of the 17th Century. London: Secker & Warburg, 1958, his Intellectual Origins of the English Revolution. Oxford: The Clarendon Press, 1965 and Society and Puritanism in Pre-Revolutionary England. London: Secker & Warburg, 1964. All of Hill’s works spoke to both my bolshie youth, such as it was, and my interest in religious ideas and their social effects. J.H. Plumb was for me a model of accessible history writing with his interest in the social: England in the Eighteenth Century. London: Pelican Books, 1950 and Men and Places: London: Cresset Press, 1963; and Eric Hobsbawm. The Age of Revolution 1789-1848. London: Abacus, 1962. Hobsbawm’s Primitive Rebels: Studies in Archaic Forms of Social Movement in the 19th and 20th centuries. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1959 was an ignition point for my doctoral studies on colonial resistance movements.

Most are still on my bookshelves. Lest one think my undergraduate history was mainly a tour of English history, D.P. Crook, ed. Questioning the Past. A Selection of Papers in History and Government. St Lucia: University of Queensland Press, 1972 contains essays on a range of areas and themes by many of the people who taught me. Besides those I have named, they include Chris Penders on Indonesian history, Glen St John Barclay who taught international relations with verve and perspicacity, Crook himself on Stuart England, Charles Grimshaw and Don Dignan. Note they are all male. In those days a female historian at UQ was rare, though I remember lectures by June Stoodley and Noela Deutscher on aspects of Queensland history. The theory works I most remember from undergraduate struggles with theory are William Dray. Laws and Explanation. London: OUP, 1957 and Patrick Gardiner. The Nature of Historical Explanation. London: OUP, 1952). But R.G. Collingwood’s The Idea of History. Oxford: The Clarendon Press, 1946 suited me down to the ground.

John Moses has written on a vast canvas stretching from German intellectual history through trades union history, Pacific history, biography and theology. He has remained close to me as a colleague and friend whose genuine passion for truth-telling in German and Australian history fires him still into his 90s. I mention just a representative three from his oeuvre: The Politics of Illusion: The Fischer Controversy in German Historiography. London: George Prior, 1975; The Reluctant Revolutionary: Dietrich Bonhoeffer’s Collision with Prusso-German History. New York: Berghahn Books, 2009; and with Peter Overlack. First Know Your Enemy: Comprehending Imperial German War Aims and Deciphering the Enigma of Kultur. North Melbourne: Australian Scholarly Publishing, 2019. Moses has no time for the revisionist history of Christopher Clark, an Australian historian at Cambridge, and what he sees as Clark’s exculpation of Germany’s primary role in the outbreak of World War I: The Sleepwalkers: How Europe Went to War in 1914. London: Allen Lane, 2012. His article on Wilhelm Solf that first sparked my interest in this cultivated, conservative but flexible character was “The Solf Regime in Samoa: Ideal and Reality.” The New Zealand Journal of History 6, no.1 (1972): 42-56.

My first readings in the history of the Pacific, beyond dabbles in Australian colonial and foreign policy, were the classic works on Samoa and Tonga: F.M. Keesing. Modern Samoa. Its Government and Changing Life. London: Allen & Unwin, 1934; J.W. Davidson. Samoa mo Samoa. The Emergence of the Independent State of Western Samoa. Melbourne: OUP, 1967; R.P. Gilson. Samoa 1830-1900: The Politics of a Multi-Cultural Community. Melbourne: OUP, 1970; and Noel Rutherford. Shirley Baker and the King of Tonga. Melbourne: OUP, 1971. They pushed me onto a range of ethnographic texts on Polynesian and Melanesian societies. I was so grateful to my German language training for it enabled me to read Augustin Krämer in the original: Die Samoa-Inseln: Entwurf einer Monographie mit besonderer Berücksichtigung Deutsch-Samoas. Stuttgart: Schweitzerbart Verlag, 2 vols. 1902.

My debt to German historical literature is deep and wide. I will mention only a work that was a particular inspiration as I began postgraduate research, Helmut Bley’s Kolonialherrschaft and Sozialstruktur in Deutsch Südwestafrika, 1894-1914. Hamburg: Leibniz Verlag, 1968, later translated as South-West Africa under German Rule, 1894-1914. London: Heinemann, 1971. With its attention to sociological features of colonial power on the ground, it was a model for what I wanted to do in my work. I later worked with Bley in Hannover. Much of my doctoral time was spent in the split Germanies, studying diametrically opposed historical literatures on their colonies in Africa and the Pacific. When I was in England, in Oxford, my debt to Colin Newbury was constant and deep, though less for his written works (which were legion and some wrestled with ‘resistance and adaptation’) but for his support, both intellectual and emotional as I made my way through leather-patched and Harris-tweeded Oxford. But the following of his works should be mentioned for they have had an influence on my understanding of the power dynamics in colonial situations: Tahiti Nui: Change and Survival in French Polynesia 1767-1945. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 1980; and Patrons, Clients and Empire: Chieftaincy and Overrule in Asia, Africa and the Pacific. Oxford: OUP, 2003.

The works that made most impact on me during those Oxford years were largely African history based: John Iliffe. A Modern History of Tanganyika. Cambridge: CUP, 1979; Ronald Robinson and John Gallagher with Alice Denny. Africa and the Victorians: The Official Mind of Imperialism. London: Macmillan, 1961; David Fieldhouse. The Theory of Capitalist Imperialism. London: Longmans, 1967; R.I. Rotberg and Ali Mazrui, eds. Protest and Power in Black Africa. New York: OUP, 1970; R.Maunier. The Sociology of Colonies: Introduction to the Study of Race Contact. trans. E.O. Lorimer. London: Routledge, 1949; Terence Ranger. Revolt in Southern Rhodesia 1896-1897. London: Heinemann, 1967; and his edited Emerging Themes in African History. London: Heinemann, 1968. I was yet to find the work of James C. Scott and his studies of South-East Asian resistance modes. The quotation about ‘a certain subaltern response’ on my part to Oxford ways is from Brij V. Lal, ed. Pacific Islands History: Journeys and Transformations. Canberra: Journal of Pacific History Monographs, 1992, p.62.

The book that came out of my doctoral expeditions and the post-doctoral fieldwork I was enabled to do in the islands was Pacific Islanders under German Rule: A Study in the Meaning of Colonial Resistance. Canberra: ANU Press, 1978 (republished by ANU eView, 2016)). It dealt with Germany’s three colonial spheres in Polynesia, Melanesia and Micronesia, and though not strictly a comparative study it aligned them against a theory of colonial resistance that drew on the African and German history themes I had been studying. My colleague at Newcastle, Noel Rutherford, and I followed up with a selection of essays meant as a teaching tool in the Pacific: Protest and Dissent in the Colonial Pacific. Suva: Institute of Pacific Studies, 1984. Cheaply produced and printed just a word-processors were coming online, it has had a longer life than any other work and with its white fist against a red background on the front cover made us look like agents provocateur.

My essays in biography have each been very different. The first was a full-blown work that benefited from touring all the places my subject had lived and worked, trying to recreate his environments, as well as testing my ability to climb into Anglican church culture from outside: The Meddlesome Priest: A Life of Ernest Burgmann. St Leonards: Allen & Unwin, 1993. The second – a joint endeavour, itself a challenge – experimented with a series of conversations between the chapters on our methods and our personal journeys around the character of Wilhelm Solf within Germany’s catastrophic twentieth century history: with Paula Tanaka Mochida. The Lost Man. Wilhelm Solf in German History. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag, 2005. The third, on Derek Freeman was an attempt to place his personality and character within the context of the anthropological debates about Margaret Mead and Samoa, debates in which Freeman skewered opponents and was himself skewered, both during his long life and after his death: Truth’s Fool. Derek Freeman and the War over Cultural Anthropology. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 2017. The remark by P.B. Waite is from his “Invading Privacies: Biography as History.” Dalhousie Review 69, no. 4 (1990): 494.

The Pacific part of my writing has included New Zealand while I was there for a decade. For the debates about ‘pakeha gatekeepers’ writing lives of Maori, see Michael King. Being Pakeha Now: Reflections and Recollections of a White Native. Auckland: Penguin, 2004 c 1985. Looking back across the Tasman with Kiwi colleagues resulted in Remaking the Tasman World. Christchurch: Canterbury University Press, 2008 with Philippa Mein Smith and Shaun Goldfinch. Other pieces allowed me – at a distance – to worry about my Pacific-ness during this whole writing life, one under a nom de plume, John Adolphus (my middle names) in the little volume that Brij Lal brought out at the ANU to encourage people to reflect upon their positions in the world (“Manoa Metaphors.” Conversations 2, no.2 (December 2001): 28-33). Another was the paper I gave about the difficulty for a Pacific ‘outsider’ to do biography when it involved Pacific Islanders (“Sniffing the Person: Writing Lives in Pacific History” in Brij V. Lal & Peter Hempenstall, eds. Pacific Lives, Pacific Places. Bursting Boundaries in Pacific History. Canberra: Journal of Pacific History Monographs, 2001: 34-46.

The cynical statement about my ‘second-hand discourse’ comes from Pacific Islands History: Journeys and Transformations, p.78. The Greg Dening quote used in that essay came from his “Reflection: On the Cultural History of Marshall Sahlins and Valerio Valeri.” Journal of Pacific History: Bibliography and Comment 23 (1988): 45-46. The reminder from Tessa Morris Suzuki is in a thoughtful piece “Mapping Time and Space” in her On the Frontiers of History: Rethinking East Asian Borders. Canberra: ANU Press, 2020: 25-46. Finally, the reference to Inge Clendinnen’s history writing came from Jay Winter’s obituary for her in Australian Historical Studies 48, no.2 (2017): 280-282.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Adolphus, John. “Manoa Metaphors.” Conversations 2, no.2 (December 2001): 28-33.

Bley, Helmut. Kolonialherrschaft and Sozialstruktur in Deutsch Südwestafrika, 1894-1914. Hamburg: Leibniz Verlag, 1968 [later translated as South-West Africa under German Rule, 1894-1914. London: Heinemann, 1971].

Breasted, J.H. Ancient Times: A History of the Early World. Boston: The Athenaeum Press, 1935.

Clark, Christopher. The Sleepwalkers: How Europe Went to War in 1914. London: Allen Lane, 2012.Collingwood, R.G. The Idea of History. Oxford: The Clarendon Press, 1946.

Crook, D.P. ed. Questioning the Past. A Selection of Papers in History and Government. St Lucia: University of Queensland Press, 1972.

Davidson, J.W. Samoa mo Samoa. The Emergence of the Independent State of Western Samoa. Melbourne: OUP, 1967.

Dening, Greg. “Reflection: On the Cultural History of Marshall Sahlins and Valerio Valeri.” Journal of Pacific History: Bibliography and Comment 23 (1988): 43-48.

Dray, William. Laws and Explanation. London: OUP, 1957.

Elton, Geoffrey. The Tudor Revolution in Government: Administrative Changes in the Reign of Henry VIII. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1953.

Elton, Geoffrey. England under the Tudors. London: Methuen, 1955.

Fieldhouse, David. The Theory of Capitalist Imperialism. London: Longmans, 1967.

Gardiner, Patrick. The Nature of Historical Explanation. London: OUP, 1952.

Gilson, R.P. Samoa 1830-1900: The Politics of a Multi-Cultural Community. Melbourne: OUP, 1970.

Hempenstall, Peter. Pacific Islanders under German Rule: A Study in the Meaning of Colonial Resistance. Canberra: ANU Press, 1978 [republished by ANU eView, 2016].

Hempenstall, Peter. “’My Place’: Finding a Voice Within Pacific Colonial Studies.” In Pacific Islands History. Journeys and Transformations, edited by Brij V. Lal, 60-78. Canberra: Journal of Pacific History Monographs, 1992.

Hempenstall, Peter. The Meddlesome Priest: A Life of Ernest Burgmann. St Leonards: Allen & Unwin, 1993.

Hempenstall, Peter. “Sniffing the Person: Writing Lives in Pacific History.” In Pacific Lives, Pacific Places. Bursting Boundaries in Pacific History, edited by Brij V. Lal & Peter Hempenstall, 34-46. Canberra: Journal of Pacific History Monographs, 2001.

Hempenstall, Peter. Truth’s Fool. Derek Freeman and the War over Cultural Anthropology. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 2017.

Hempenstall, Peter and Noel Rutherford. Protest and Dissent in the Colonial Pacific. Suva: Institute of Pacific Studies, 1984.

Hempenstall, Peter and Paula Tanaka Mochida. The Lost Man. Wilhelm Solf in German History. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag, 2005.

Hill, Christopher. Puritanism and Revolution: Studies in Interpretation of the English Revolution of the 17th Century. London: Secker & Warburg, 1958.

Hill, Christopher. Society and Puritanism in Pre-Revolutionary England. London: Secker & Warburg, 1964.

Hill, Christopher. Intellectual Origins of the English Revolution. Oxford: The Clarendon Press, 1965.

Hobsbawm, Eric. Primitive Rebels: Studies in Archaic Forms of Social Movement in the 19th and 20th centuries. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1959.

Hobsbawm, Eric. The Age of Revolution 1789-1848. London: Abacus, 1962.

Iliffe, John. A Modern History of Tanganyika. Cambridge: CUP, 1979.

Joyce, R.B. Sir William MacGregor. Carlton: Melbourne University Press, 1971.

Keesing, F.M. Modern Samoa. Its Government and Changing Life. London: Allen & Unwin, 1934.

King, Michael. Being Pakeha Now: Reflections and Recollections of a White Native. Auckland: Penguin, 2004 c 1985.

Krämer, Augustin. Die Samoa-Inseln: Entwurf einer Monographie mit besonderer Berücksichtigung Deutsch-Samoas. Stuttgart: Schweitzerbart Verlag, 2 vols. 1902.

Lawrence, Peter. Road Belong Cargo: A Study of the Cargo Movement in the Southern Madang District, New Guinea. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1964.

Leopold, Keith. Introducing German. Sydney: Angus & Robertson, 1964.

Maunier, R. The Sociology of Colonies: Introduction to the Study of Race Contact. trans. E.O. Lorimer. London: Routledge, 1949.

Mein Smith, Philippa, Peter Hempenstall and Shaun Goldfinch. Remaking the Tasman World. Christchurch: Canterbury University Press, 2008.

More, Thomas. Utopia: The English Translation thereof by Raphe Robynson. Second Edition, 1556. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1965.

Moses, J.A. “The Solf Regime in Samoa: Ideal and Reality.” The New Zealand Journal of History 6, no.1 (1972): 42-56.

Moses, J.A. The Politics of Illusion: The Fischer Controversy in German Historiography. London: George Prior, 1975.

Moses, J.A. The Reluctant Revolutionary: Dietrich Bonhoeffer’s Collision with Prusso-German History. New York: Berghahn Books, 2009.

Moses, J.A. with Peter Overlack. First Know Your Enemy: Comprehending Imperial German War Aims and Deciphering the Enigma of Kultur. North Melbourne: Australian Scholarly Publishing, 2019.

Murphy, D.J. T.J.Ryan, a Political Biography. St Lucia, U of Queensland Press: 1975.

Newbury, C.W. Tahiti Nui: Change and Survival in French Polynesia 1767-1945. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 1980.

Newbury, C.W. Patrons, Clients and Empire: Chieftaincy and Overrule in Asia, Africa and the Pacific. Oxford: OUP, 2003.

Plumb, J.H. England in the Eighteenth Century. London: Pelican Books, 1950.

Plumb, J.H. Men and Places: London: Cresset Press, 1963.

Ranger, Terence O. Revolt in Southern Rhodesia 1896-1897. London: Heinemann, 1967.

Ranger, Terence O. ed. Emerging Themes in African History. London: Heinemann, 1968.

Reynolds, Henry. The Other Side of the Frontier: An Interpretation of the Aboriginal Response to the Invasion and Settlement of Australia. Townsville: James Cook University, 1981.

Robinson, Ronald and John Gallagher with Alice Denny. Africa and the Victorians: The Official Mind of Imperialism. London: Macmillan, 1961.

Rotberg, R.I. and Ali Mazrui, eds. Protest and Power in Black Africa. New York: OUP, 1970.

Rowley, C.D. The Destruction of Aboriginal Society. Canberra: Australian National University Press, 1970.

Rowley, C.D. Outcasts in White Australia. Canberra: Australian National University Press, 1971.

Rowley, C.D. The Remote Aborigines. Canberra: Australian National University Press, 1971.

Rowley, C.D. A Matter of Justice. Canberra: Australian National University Press, 1978.

Rutherford, Noel. Shirley Baker and the King of Tonga. Melbourne: OUP, 1971.

Suzuki, Tessa. “Mapping Time and Space.” In On the Frontiers of History: Rethinking East Asian Borders. Canberra: ANU Press, 2020: 25-46.

Virgil. The Aenid. Trans. Robert Fitzgerald. London: Vintage Books, 1990.

Waite, P.B. “Invading Privacies: Biography as History.” Dalhousie Review 69, no. 4 (1990): 479-495.

Winter, Jay. “Obituary: Inge Clendinnen 1934-2016.” Australian Historical Studies 48, no.2 (2017): 280-282.