Born in Melbourne, Pauline Nestor studied and taught at the University of Melbourne before going to Oxford to read for an MPhil and then a DPhil in English. She returned to Australia to take a post at Monash University where she taught English and continued her research, specialising in the work of nineteenth-century English women writers. Her published works include Female Friendships and Communities: Charlotte Bronte, George Eliot and Elizabeth Gaskell, Charlotte Brontë and Critical Issues: George Eliot. From 2007, Nestor also became involved in academic administration and leadership, taking on the roles of Associate Dean Research in the Arts faculty and Senior Vice Provost Research at Monash. This narrative is excerpted from an interview with the Rhodes Trust on 10 March 2024.

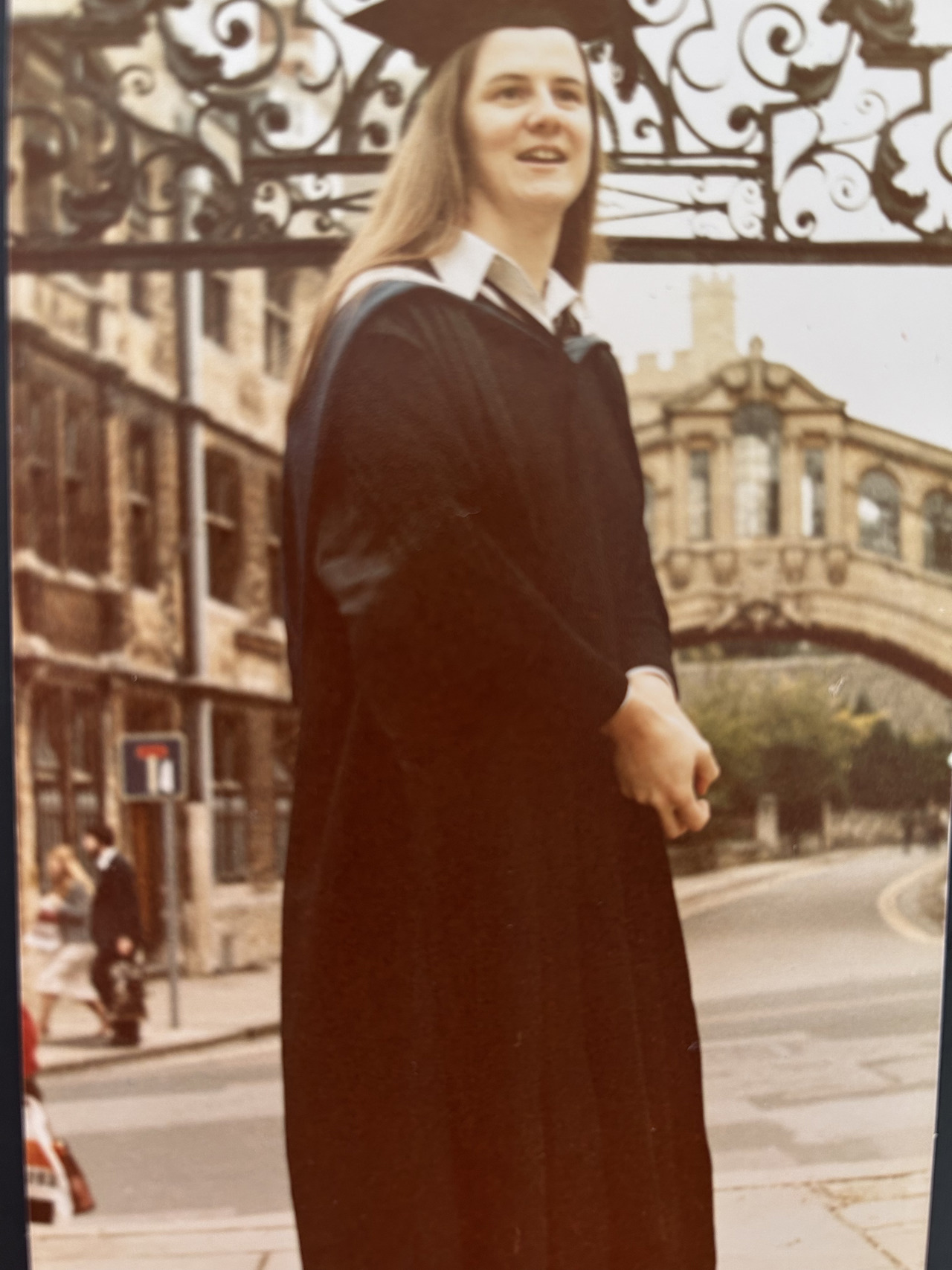

Pauline Nestor

Australia-at-Large & St Catherine's 1978

‘Opportunities were put in my way that I might not have expected’

I was born and grew up in the northern suburbs of Melbourne and I had a very happy childhood. I was one of five children and we had a fairly outdoor existence, riding our bikes for miles and playing outside, even after dark. My father was a police constable, so there wasn’t a lot of money to go around. Nobody from my family had ever gone to university. It was not a studious household and there weren’t many books. So, although I got a great deal of love and encouragement from my family, I didn’t get a lot of cultural capital.

I went to a Catholic parochial school where about 75% of the intake were children of migrants and it was great. It emphasised community and my experience was that the nuns really encouraged us. Opportunities were put in my way that I might not have expected given my background. I was given public speaking lessons and put up for leadership awards and encouraged in drama, and I was especially fortunate to have great English teachers.

On applying for the Rhodes Scholarship

I went on to do a four-year honours degree at the University of Melbourne, in English and History. Because I was in the honours stream, I was a part of a smaller cohort and we were so excited by our studies. We thought we were Matthew Arnold, holding back the barbarians at the gates. We would sit up until four in the morning in earnest conversation about whether Conrad’s Nostromo was a great novel or not, or, when the Shakespeare seminar wasn’t working, the students would have preliminary seminars to do the groundwork so that the actual seminar would work. We had a sense of purpose, and it was exhilarating. I ended up working on the nineteenth-century novel and I have lived and breathed and probably lived in the nineteenth-century novel ever since.

When I graduated, I was given an untenured job teaching in the English department there. By that stage, if you intended to have a permanent career in literature, you needed to get an overseas degree at either Oxford or Cambridge. So, I started to save up, and then Maggie Tomlinson, this wonderfully flamboyant woman in my department, said, ‘You should apply for the Rhodes Scholarship.’ I think that’s quite important, and I still mentor students who are thinking of applying from my university, because a lot of people won’t think of it unless they are encouraged. I applied in the first year that the Scholarship was open to women, and I was runner up. I remember I rang my mother after the interview and said, ‘Well, that hasn’t worked out very well. It was a bit like having an argument with Dad at the dinner table.’ But the committee encouraged me to apply again the following year, and I got it. When I won the Scholarship, one of the things that gave me the greatest pleasure was the pleasure it gave to my family. And this isn’t relevant anymore, but Catholics didn’t often get the Rhodes Scholarship in those days, because the establishment was still very Church of England. So, it was the biggest thrill for my family and my community.

‘In some ways, it was a baptism of fire’

I was very apprehensive about leaving home because I knew how much I would miss everyone, but I was also fairly hard-headed about it. I went across to the UK three weeks early and stayed in London, going to the theatre ever night to get that out of my system so I could go to Oxford and work really hard, which I did. I found aspects of Oxford daunting. We were never given reading lists, for example, and my supervisor would reel off these names, with arcane English pronunciation, and you just wrote them down and hoped you could find them in the Bodleian’s catalogue. So, in some ways then, it was a baptism of fire, but in other ways it was an absolute thrill. It’s an extraordinarily beautiful city and the Bodleian is a magnificent library. If anything, though, it was the not that the quality of the teaching was so much higher than what I had been used to, but the standard produced by my fellow students encouraged me to do much better. Oxford opened worlds for me, and I am deeply grateful for that.

There were very few colleges that admitted women at that point. I had been advised not to go to a graduate college, so I chose St Catherine’s, but I think that was a mistake. I had already done a degree and had been teaching for three years, and so my patience with the standard undergraduate high jinx was worn pretty thin. In my second year, I moved out to a shared house and then, when I did my DPhil, I got a junior research fellowship at Wolfson College and moved there. That suited me far better. It was much more international, there were families with children living there, there was no high table – it seemed a more adult environment. Scholars didn’t have a great deal to do with Rhodes House then, but the Rhodes money did mean that I was able to travel to Yale to do some work on George Eliot as well as travelling to visit friends. If you’re trying to do a DPhil in two years, though, you don’t travel around much!

‘The advent of feminism certainly suited me’

I’d been given an extra year so that I could do my DPhil, but I was self-financing and determined to do it very quickly. I think I broke the land speed record: I finished in just over two years. I was working on women writers in the nineteenth century and I didn’t have much input in terms of supervision, but I was always fairly self-motivated so I didn’t find that a great handicap. I actually did my viva just 48 hours before I left Oxford to start my new job in Australia, at Monash University, and one of my examiners, Marilyn Butler, contacted me before I left and told me that she would recommend that Oxford University Press publish my thesis, which is what happened. At that time, it was at the start of the interest in women’s literature. My research had been on how female writers formed friendships and communities. It was partly historical, partly literary. And then, when I was in Australia, I got a letter from Macmillan saying that Marilyn Butler had suggested I would be well placed to write the book they wanted on the Brontës. So, I got enormous help, and with the kind of generosity that was exceptional but very characteristic of her.

This is now my 42nd year at Monash. I taught in the English department for a long time, and then in about 2007 I became Associate Dean Research in the Arts faculty. After that, I had a variety of roles, including, finally, Senior Vice Provost Research. I retired from my substantive position in 2018 but I am still involved in the university. A lot has changed in my field since I started teaching. The advent of feminism certainly suited me, and feminism is always evolving and being challenged and becoming more inclusive. In my own work, I’ve been particularly interested at looking at the non-heroic aspect of women’s lives, the social history. Alongside teaching and research, I’ve also been involved with university administration and leadership. I’m not especially imaginative, but I’ve got a very clear mind, and it’s been a real honour to be able to work to help translate the ideas that academics have into language that will be understood by the outside world. Facilitating their vision has been one of the absolute pleasures of my career.

‘Middlemarch would be my desert island novel’

I think that literature and history can change lives. When I taught students, I didn’t want them to just come in and emote: I wanted them to understand the artistry of the text but also understand that what they were reading had the capacity to open worlds or to challenge them. My last book, for example, was on George Eliot’s ethics, and I think if reading Eliot doesn’t do something to inform your ethics or your ideology or your emotional intelligence, then you’re not reading carefully enough. Virginia Woolf said Middlemarch was the first novel for adults in the English language and I think it is the most humane and profound and intelligent and remarkable book. I have say that Middlemarch would be my desert island novel.