Born in Grand Forks, North Dakota in 1966, Paul Markovich attended Colorado College before going to Oxford to read for a second BA in PPE (Philosophy, Politics and Economics). After a period working as a strategic consultant for Booz Allen Hamilton, Markovich moved to work for the healthcare plan Blue Shield of California. He left the organisation for a period of time, founding MyWayHealth, and then returned to Blue Shield of California, where he rose to become President and CEO. While continuing to hold this role, he also co-chaired California’s COVID-19 testing task force and went on to spearhead the rollout of vaccines in the state. In January 2025, Paul became the President and Chief Executive Officer of Ascendiun, a nonprofit parent company to Blue Shield of California. This narrative is excerpted from an interview with the Rhodes Trust on 3 May 2024.

Paul Markovich

North Dakota & University 1989

‘The community would really pull together’

I really enjoyed growing up in Grand Forks. There was a strong sense of community there which valued work ethic, humility, honesty, and authenticity. Grand Forks is right along the banks of the Red River, and typically, every spring, the river would flood. I remember when that happened, we would all go fill sandbags and try to help, irrespective of whether they were our houses or not. The community would really pull together.

My parents both eventually taught at the University of North Dakota, although my mom didn’t actually start teaching there until she got her PhD just before I went into high school. It was a real middle-class upbringing, and I was the middle child of three. My kindergarten teacher shared with my parents that she thought I was slow, and my mom was upset by that. I remember one of the things my mom wanted to do after the Rhodes announcement came out was track down my kindergarten teacher to let her know!

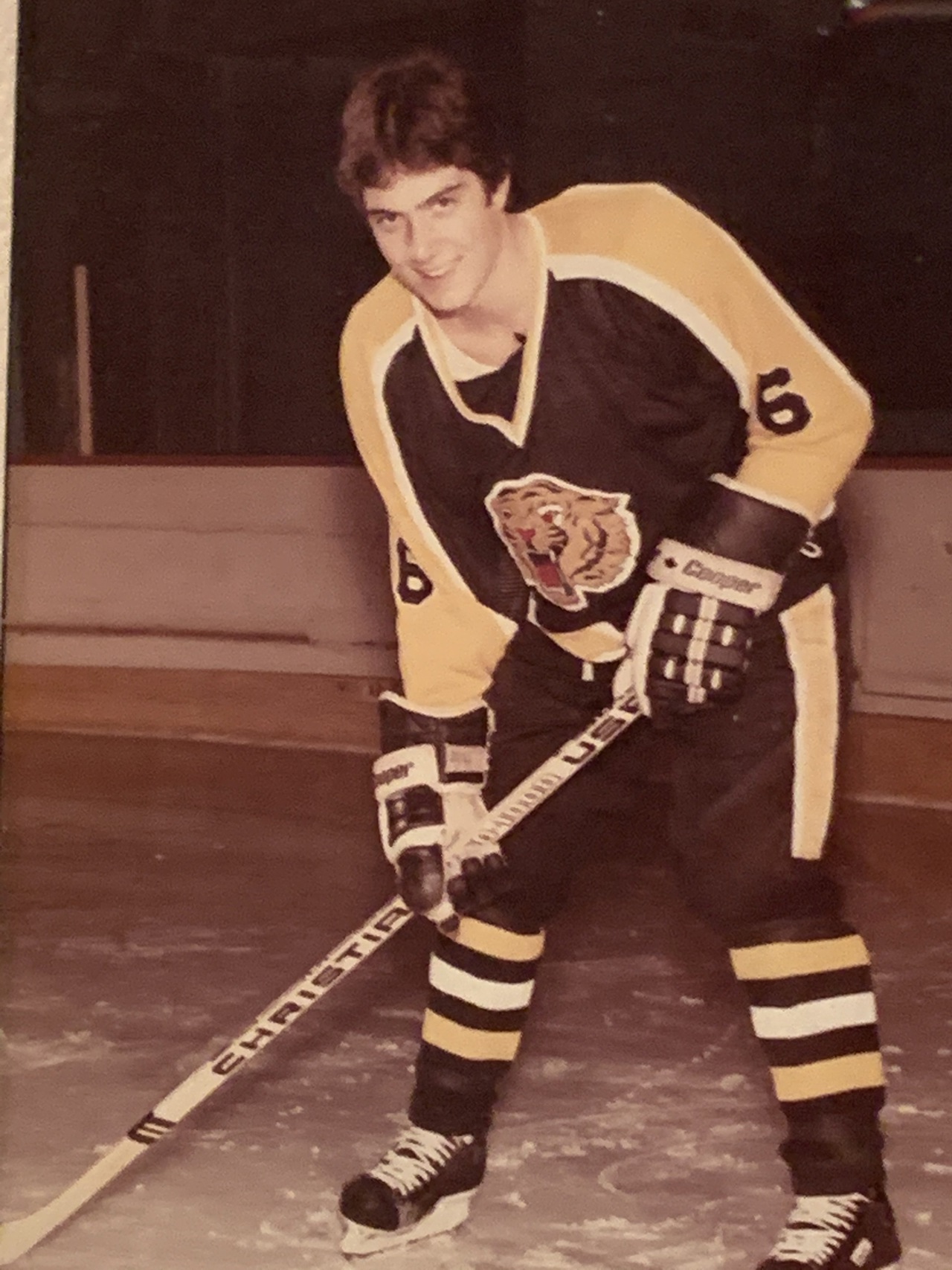

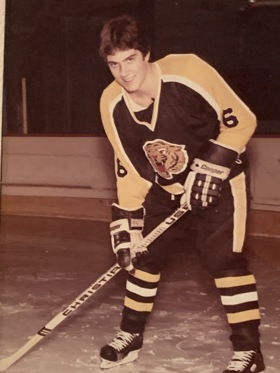

I went to a Catholic elementary school, and, although it was never heavy-handed, there was always this sense of morality and the need for compassion towards your fellow man. I remember that feeling was core to everything that went on there. At school, I was always active playing sports, and when it was winter, my friends and I would just spend the day skating. I kept up that interest in athletics, and I also took my academics seriously. The hard math and science always came pretty naturally to me, and I liked anything where there was a natural logic and it was rules-based. I also really enjoyed civics and politics and history.

I started off thinking I wanted to be a professional hockey player, and that stayed with me until the end of high school. Then I began to realise that, although I wanted to play in college, I probably didn’t have enough talent to become a professional. I thought about academia, because I saw my parents doing that, and I also wondered whether I could run for political office, because I knew I had an interest in and talent for leadership.

On applying for the Rhodes Scholarship

I chose Colorado College because it had the perfect combination of academics and athletics. I wanted the academic experience as well as the hockey experience, and that’s what I got there. It was a great school. You always got taught by a professor in a small-class environment, and at the same time, I was able to develop my hockey playing and eventually join the team. Then, I was injured, and I had to have some surgeries and do a lot of rehabilitation, and although I did carry on playing, it was difficult. I think it was an important learning experience for me, that sometimes, perseverance and persistence alone can’t get you where you’d like to be.

My parents had mentioned the Rhodes Scholarship to me quite a few times, but I wasn’t that interested at first. Then, I was talking to them about how I was looking to go to graduate school and would be interested in studying overseas and they said, again, ‘Well, there’s this great scholarship…’ So, I threw my hat in the ring in earnest. In the interview, I remember being asked, ‘What’s the world’s fight for you?’ and the question really stuck with me. I had been thinking for some time about how we all have an obligation to make the world a better place, and I was only just beginning to think about how I could do that, so being asked that question very much crystallised my focus.

‘Oxford was different and fascinating’

When I got to Oxford, I was still thinking that I might go into either politics or academia, but while I was there, things started to shift for me. As I was studying in a more advanced way in each of economics and politics, it was becoming less and less interesting to me, in part because it wasn’t that practical. I remember sitting in a discussion of exactly how poverty should be defined and thinking, ‘Why are you spending all of this energy on how to fix the definition? We know there’s poverty in the world. What are we going to do about it?’ So, I got a little disenchanted with the idea of more education, and I also began to realise that politics might not be a space where I could use all of my time to solve problems.

Oxford was different and fascinating for me. The combination of English culture and academic culture made it a far more formal place than I had experienced before. Also, the buildings are so historic that it’s almost like you’re walking into some version of a castle: these beautiful, pristine quads and ancient buildings. The downside, though, was that the fixtures were old too. And the food at that time in college was not so great. I was saved by the fact that there was such good and reasonably priced food outside college, especially Indian food, but I did still find myself wondering why the English would call a dish ‘Toad in the hole!’

‘It was just so rewarding’

When I left Oxford, I went to work for Booz Allen Hamilton. I learned so much, working across a number of sectors, and then I got asked to join a group that was trying to figure out how the healthcare space was going to deal with these things that were just emerging called Health Maintenance Organizations. When I looked at the materials, the whole ‘Fighting the world’s fight’ question just clicked in for me, because I realised this was a system that wasn’t working as it should be working. And I saw that if you could improve healthcare, you could truly impact lives.

I took up the role at Blue Shield of California because I liked their approach and what they were trying to do as a mission-driven non-profit. For a time, later on, I moved away and went through the experience of founding a startup, but eventually, I realised that if I wanted to make big changes in healthcare, I needed to do it from inside an organisation that had clout and market share. I was promoted through the organisation, and eventually I became President and CEO, but I learned a lot along the way about how I needed to do things differently. For a long time, I was primarily in my head, looking at strategy and driving improvements. It took me a while to realise that making things work is about relating to people and bringing your heart into your work too. I’m not saying I’m brilliant at it now, but I’m certainly a lot better than I used to be.

My work during the COVID-19 pandemic came about just because I could see that there were problems that needed to be solved: California wasn’t testing nearly enough people fast enough, and later, the same problem emerged with the vaccination programme. For both testing and vaccination, we were able to boost capacity massively. It was an incredibly intense period of time, but when I saw the 2023 study about how around 20,000 lives were most probably saved by the speed of the California vaccine rollout, that was just so rewarding.

‘Fulfilment comes from feeling like, “My work, my life, has meaning”’

One of my hopes for the Scholarship is that it will systematically help Scholars with their own journey to answer that question of, ‘What’s the world fight?’ There is an infinite number of ways you can have a positive impact on the world, and I would really encourage all Scholars to dig deep and find out what matters to them and what makes them feel fulfilled. That isn’t just about our time at Oxford: that question should stay with us, at every stage in our lives, and reflecting on it is hugely powerful.

So often, I see people seeking out what society thinks they should, whether that’s the next promotion or a certain amount of money. But happiness is priceless. Figure out what makes you happy. I’m very happy what I’m doing in my professional life, and my family is the light of my life, for sure. I’ve got an incredible partner and best friend in my wife, Lisa, and she and our children mean the world to me. I’ve been so blessed in my life. I think that happiness comes from being fulfilled, and fulfilment comes from feeling like, ‘My work, my life, has meaning.’

Transcript

Interviewee: Paul Markovich (North Dakota & University 1989) [hereafter ‘PM’]

Moderator: Jamie Byron Geller [hereafter ‘JBG]

Date of interview: 3 May 2024

[begins 00:04]

JBG: So, we are now recording. This is Jamie Byron Geller on behalf of the Rhodes Trust, and I have the pleasure of being here today with Paul Markovich (North Dakota & University 1989) to record Paul’s oral history interview. Today’s date is 3 May 2024 and Paul’s interview will help us to launch the first ever comprehensive Rhodes Scholar Oral History Project. Thank you so much, Paul, for joining us in this project. Before we start, would you mind saying your full name for the recording, please?

PM: Sure, Jamie. It’s my pleasure to be here. I am Paul Markovich and I’m president of Blue Shield of California.

JBG: Wonderful. Thank you. And Paul, do I have your permission to record this interview?

PM: Yes, you do.

JBG: Wonderful. Thank you. So, we’re having this conversation on Zoom, Paul, but where are you joining from today?

PM: I’m in Oakland, California, which is where our company is headquartered.

JBG: Great. And so, how long as Oakland been home?

PM: We moved here in 1995, so it’s been just shy of 30 years that we have lived, not just in the San Francisco Bay area in Oakland, but actually in the same house.

JBG: Oh, wonderful. And where and when were you born?

PM: I was born in 1966 in Grand Forks, North Dakota, which is about 70 miles north of the famous or infamous Fargo, depending on how you feel about the movie and the TV series.

JBG: Great. And did you grow up in North Dakota?

PM: I did, yes. I was born and raised there. I went all the way through, graduated high school, and I left after high school to go to college at Colorado College. But all of my formative years, I’d say, through high school, were in my hometown of Grand Forks, North Dakota, which is a city of about 45,000 people.

JBG: Great. And would you mind sharing a little bit about your family growing up, Paul? So, I know you mentioned your parents were college professors?

PM: They are, yes. They were. Yes, college professors. The University of North Dakota is one of the two large universities in the state. It had, at the time at least, about 10,000 students. So, you can imagine it’s quite a college town when the entire population is about 45,000 people and there are 10,000 students. So, a lot of the life around town centred around the university. My father taught comparative politics, political science, and my mom taught finance and economics at the university, and so, yes, it was a really, I would say, genuine, kind of, middle-class upbringing in the sense that, my mom didn’t actually start teaching until I was-, she got her PhD just before I went into high school, so it was, I think, right around some time when I was in middle school that she got it. So, at first, it was just my dad that was working, and then my mom went back to school, and she started teaching later in life.

So, yes, but I really enjoyed growing up there. There is a lot of-, that community valued work ethic and humility and honesty and authenticity, and there was a real strong sense of community. Grand Forks is right along the banks of the Red River, which would flood typically every spring, just a matter of degree, sometimes severely, and so, I just remember when the floods were quite bad, we would all go fill sandbags and try to create a, kind of, manmade dam in front of people’s homes, you know, irrespective of whether they were our houses or not. That’s the kind of thing that would happen. The community would really pull together. So, I really enjoyed it. I felt like the values there and the sense of community and the environment was just a wonderful environment to grow up in.

JBG: Lovely. Thank you for sharing that. Do you have siblings, Paul?

PM: I do. I have an older sister, two years older than I am, and a younger brother who is about two and a half years younger. So, there were three of us growing up, and I’m a middle child.

JBG: Great. And I would love to know a little bit about your earliest educational experiences, what your elementary and high school experiences were like.

PM: Well, it’s kind of funny. Like, even my kindergarten teacher thought I was slow, and I remember that she shared that with my parents, and my mom was very upset by that, because she adamantly disagreed with that notion. But they also discovered that when I would go walk to school on my own, I was so curious about my environment that I would always stop and pause and, kind of, look at the trees and that sort of thing. So, I kept showing up to school late, and they couldn’t figure out why, because it was, like, a three-minute walk from the house to the class, and then one day, they followed me and they discovered me just, kind of, curiously gazing around and figuring out what was what. So, one of the things my mom told me that she wanted to do after the Rhodes announcement came out was track down my kindergarten teacher and send her the article about me becoming a Rhodes Scholar, just to prove the point that I wasn’t slow.

But I actually went to elementary school at a Catholic elementary school, and so, I mean, it was an academic environment, for sure, but there was also a religious and moral component, I’d say, to the education that was going on, and I would say about half of my teachers going through elementary school were nuns. But at the same time, it never felt heavy handed, the education there. It always felt spiritual, though, I would say, in the sense that, we always would have some kind of mass on Friday, and I was occasionally an altar boy, and having to figure out when to ring the bell at the right time. There was always this sense of needing or wanting to imbue in the students, myself included, this sense of morality and this sense of compassion toward your fellow man.

So, I don’t remember too much about the actual academic side of things, but I do remember feeling that that was core to everything that they did, was that sense of wanting to help these young students learn how to do the right thing in their lives. So, that was my memory of elementary school, and middle school-, I don’t know, I think it’s just an awkward time for everybody and the coming-of-age stuff, it’s just difficult and challenging. I was always very active playing sports, and that was the main social activity when I was younger. My parents did have me take piano lessons, and I did other things, but boy, whenever our friends got together, we might play pick-up baseball or pick-up basketball or, when it was winter, we’d just take our skates on the weekend and grab a lunch and go to the warming house three blocks away and go play pick-up hockey. So, we got cold, and then we’d come in and warm up, and then we’d have lunch, and then we’d just go skate again. We’d just spend the day there. And so, a lot of my social life, especially with friends, centred around sports and playing sports.

JBG: Great. And what was your high school like? Did you attend a Catholic high school as well?

PM: No. Once I got out of elementary school, both middle school and high school were public schools. Yes. In high school, I was just very active in a lot of things. I was in speech and debate at times. I sang with the choir and the pop singers. And of course, I played on the hockey team and the tennis team. I was the student council president as well. So, I felt like, in high school, first of all, it was just bigger. There were more students there than in middle school. There were more activities [10:00], and I felt like I started to find my voice, being a leader. There were various things that came up, for example, in my capacity-, I was captain of the hockey team, so I’d speak publicly. I was doing speech and I would speak publicly in those situations, and yes, student council president in my senior year, I’d make different decisions and give different talks. And I gave a speech at our graduation that I still really like and was passionate about at the time. So, one of the things I recollect about high school-, I remained very active in extracurricular activities, obviously took my academics seriously, and a lot of those extracurriculars were athletic in nature, but I do remember I never felt like I was leading in middle school. I just felt like I was trying to figure everything out. But I did feel like I was leading when I was in high school. So, I became a leader when I was in high school.

JBG: And were there particular academic subjects that you gravitated toward during that time?

PM: Well, the hard math and science always came pretty naturally to me, and so, I wouldn’t necessarily say that I loved the topics all the time in physics and chemistry and math. I liked them, but anytime there was a natural logic, where you put two and two together and it had to be four and it was rules-based just came very naturally to me, whereas, you know, reading Shakespearean plays was just not my thing at all. So, the English classes were always the least interesting. Like, when we did history or politics or civics, I found that interesting. I mean, I found it interesting. So, I did well in all my classes, but the ones that I felt I was most naturally good at were the more math and science-based classes, and probably the ones that I enjoyed the most were more in the civics and politics and history, and the ones that I enjoyed the least were anything related to art or literature. I don’t know, it was almost like I would develop attention deficit disorder when we would go into having to read, and we would read all the classics, so some of that was, ‘Why do I have to work so hard to, like, understand this language that is supposed to be English, but doesn’t look a lot like English to me?’

JBG: And did you have a sense when you were in high school of, for lack of a better phrase, what you wanted to be when you grew up, what your journey might look like?

PM: Well, I don’t know that I really knew what my profession was. I mean, to be honest with you, at younger ages, I thought, ‘Great, I would love to be a professional hockey player. Wouldn’t that be cool?’ You’d watch them on television and things. But I would say by the time I got farther advanced, like, towards the end of high school, I knew I wanted to play hockey in college. That was a priority for me, and I was focused on that. But I was starting to realise that I probably just didn’t have enough talent to become a professional hockey player, so I would say that that realisation started to dawn on me at the end of my high school career, that I felt like I was good enough to potentially play in college, and I made that my goal, but realising that I would top out there if I did.

So, I would say I started to shift late in my high school career to, ‘Alright, right now I’m just focused on getting into college and playing hockey there and handling my academics well, but I probably need to think about what else might happen in life.’ And I would say at that point, there were a couple of things I started to lean towards, one of which was, both my parents had doctorates, they were in academia. I just assumed that’s what everybody did. You went to high school and then you went to college and then you went to graduate school and did a PhD, because everyone in my family had a PhD. So, I started to think about academics, but then, I also started thinking about politics and elected office, the idea that, ‘Well, maybe I could do some good as an elected official.’ I mean, I did get elected student council president. So, I had won an election before, ‘Run a successful campaign,’ you know, as they say. So, I think those were the two things, as I shifted-, and I don’t know, Jamie, exactly when the shift started to happen. As I started to realise, ‘Yes, as much fun as I have playing this sport, I doubt I’ll be able to do it as a profession,’ I think it was those two things, academics and politics, that were capturing my interest.

JBG: So, playing hockey in college was certainly a goal of yours. Was that part of what brought you to Colorado College?

PM: Oh, absolutely, yes. I wanted to get a good education, and I wanted to play hockey at a Division 1 school. I had started school early. The cut-off dates for when you could start school were later when I was growing up than they are today. In today’s day and age, they would have held me back a year – not held me back a year: they wouldn’t have let me go into school as early as I did, because I came into college as a freshman, a first-year, at 17 years old. My birthday is in late October, so I turned 18 a couple of months after I got to campus, and if you think about it, a lot of what happens now, and even was happening a bit then, was, well, if you’re trying to be an athlete in college, you take a gap year. Like, you would go play in a hockey league or junior hockey, potentially, and you would get another year, another year of maturity, another year of experience, and then, you know, you would more heavily recruited, be a more appealing prospect for any college hockey programme.

The challenge for me was that, I mean, academics are really important as well, and so, a lot of the schools that were, kind of, national powers out there, with big, big student bodies – the University of North Dakota, Minnesota, Wisconsin, etc – they would only really bring players in that they thought were ready to play right then. They didn’t want to do development. They didn’t need to do development, because they could attract a big roster of players and they could have players that would try to walk on, that were on scholarship, because they had such a big student body, and they were located in such hockey playing regions – like North Dakota, Minnesota, Wisconsin – they could get a lot of depth on their roster through walk-ons that were pretty high quality and that were much more ready to play at that level than I was when I started school at the age of 17.

But for me, I didn’t want to go spend a year not studying. I mean, I wanted the academic experience as well as the hockey experience. And so, Colorado College is a small, liberal arts school. Like, the enrolment there at the time – and it’s similar today – was around 2,500 students. So, for Colorado College, they could get players in on scholarship, but they couldn’t get nearly as many walk-ons. So, they always had difficulty with depth on their roster as a result of that. So, it was a really nice fit for me. It was a great school. I felt like I could get a really good education, particularly because the class sizes-, you know, they averaged 25 students per class. You were never, like, buried in these classes with hundreds of other folks with a teaching assistant. You always got taught by a professor in a small-class environment.

And so, I really loved the academic environment there. But then, I could also show up and, kind of, have this-, I worked it out with the coach. I was like, ‘Look, I’ll walk on. I just want a chance to be on the roster, and I want a chance to improve and be better and earn a spot on the team.’ And for them, it’s, like, ‘Great.’ They’re not spending any scholarship money. They’re getting another kid on the roster who’s decent and has some upside, and I get to go to school and be on the hockey team. So, my first year, I think I played for two and half minutes. You know, they threw me into a couple of games where there were blowouts and they weren’t very close and they could dress me, but otherwise, I just practised with the team. [20:00] But then, the following year, like, I really grew and developed a lot, that first year, and then over the summer, and I physically developed a lot. I gained weight, gained strength and so, by the time I came back for my sophomore year, I was ready to play, and I cracked the lineup shortly after I got back and then played regularly that season thereafter. So, that part of it worked out really well.

JBG: Right. And you continued to play through the rest of your time in college?

PM: Well, that ended up being more of a rollercoaster, because right at the end of my sophomore year, in the last practice before the season was over, I got injured. So, I banged my knee. It wasn’t bad enough-, like, I finished the practice, and I skated out the rest of the year, but I had this, sort of, nagging knee injury, and it never quite went away, and I ultimately had to have couple of arthroscopic surgeries and do a lot of rehabilitation, so I ended up missing my junior year, from injury, and I came back and played my senior year, but I never quite got back to the same physical ability that I had before I got injured. So, that was a really frustrating but also formative experience, to realise-, because, I mean, I was 19 years old. I reached my peak of hockey playing ability at the age of 19, and it went downhill after that, and you think, ‘How’s that possible?’ You realise there are a number of things that are outside of your control and that, as important as perseverance and persistence is and was for me to get back to where I did, it’s also not enough. You know, sometimes your body just can’t do what you want it to do after an injury.

So, that was hard. I mean, it was just very, very difficult, because I had poured so much into getting to that point and making that team, and it’s hard to describe, you know, at the age of 20 and 21, how hard it is to say, ‘How is it that I know I used to be able to do these things not too long ago and now, I can’t? Or I can’t quite the same way.’ And, you know, that’s a very difficult thing, emotionally, to accept and process. So, yes, it was just a lot of, I would say, adversity and challenge. I mean, the sophomore year was my highlight. But I would also say that going through all of that – the injury, missing my junior year, just scrapping my way through my senior year, playing and practising but still having some pain and still just not being able to get to the same physical level that I had been before – there was a lot of maturity and growth that came out of that, as painful and difficult as it was, it was an important learning experience for me.

JBG: And what were you focusing on academically at that time? What were you majoring in, in college?

PM: Yes. My major was international political economy. So, I clearly split the difference between my parents. My dad was in political science, my mom was in economics: I ended up studying both. But I actually liked the interplay between politics and economics. I felt as though it was very difficult to do one without the other, because you’d be lacking too much context. You could always talk about policy changes and things you needed to do, but most of those significant policy changes need to be financed in some way, and that required a level of economic engine and economic performance and financing to understand that. And then, on the flip side, a lot of economic policy and those actual decisions that get made, you can write them down on a piece of paper or dream up great solutions as much as you want, but a lot of those decisions end up going into the political system and require political adjudication, if you will. So, I always found both topics interesting, but I felt like they were highly complementary and it was hard for me to imagine separating them.

JBG: Great. And I recall you sharing in our last conversation, Paul, that because your parents were both college professors, you had been aware of the Rhodes Scholarship, and I was wondering if you would mind sharing about what inspired you to apply, how you came to that decision.

PM: Sure. Well, yes, both my parents were quite familiar with that scholarship, given the fact that they’d taught people, and they had some students eventually try to apply for the Scholarship at points. I know that my mother, at least, had served once on a committee, one of those screening committees for interviewing and screening potential candidates for Rhodes Scholarships. So, they had started telling me, as I got further along in my college career-, you know, here I am, straight A student and playing Division 1 hockey, and they had seen, you know, through their own students that had applied for the Scholarship – in my mom’s case, having screened applications-, and they said, ‘Oh, my gosh! You’ve got this great background. You’re exactly what they’re looking for in Rhodes. Do you want to go apply for this?’ And I was, kind of, thinking, ‘Oh, I don’t know.’

The first time they talked to me about it, I just, kind of, shrugged my shoulders and said, ‘Well, maybe. It’s interesting, but-,’ It didn’t really resonate with me too much. And then later, you know, as I started to think about it-, they kept at it. You know, they kept asking, ‘Are you sure you don’t want to think about this?’ And then finally, we were having a dinner and they said, ‘Well, what do you think you want to do after college?’ and I said, ‘You know, I think I want to go to graduate school, and I think I want to go in this space.’ ‘Well, if you’re international, would you like to study overseas?’ ‘Yes, actually, that would be pretty neat to study overseas.’ ‘Well, you know, there’s this scholarship that lets you study overseas. It’s called the Rhodes.’ And I thought, ‘Yes, actually, that would be great. I should sign up for that.’ So, it, kind of, happened gradually, with my parents nudging me in that direction, but it was after, sort of, really processing what I felt made sense to come next that I threw my hat in the ring in earnest.

JBG: And I remember you sharing that there was a question you were asked during your interview process that shed light on the way that you already thought about the world, and I was wondering if you would mind speaking to that.

PM: Happy to. Yes, I’ve always had this sense, from early adulthood through today, that we all have an obligation to try to make the world a better place. You know, in some way, small medium, big way, to try and leave this world a little bit better – or hopefully, a lot better – than we found it when we entered it. So, I always believed that. Always this sense that we have an obligation to contribute, and I had been thinking about, like, ‘Well, what does that mean, and how do I do that?’ And I would say, in my college years, I was leaning more towards the idea of policy and being an elected official and helping craft and lead and make a difference in the world through that, but I hadn’t really quite been sure how I wanted to do it. But it was always a strong sense of community, and I think I got them from my parents, but also from my upbringing in North Dakota.

So, when I went for the Rhodes Scholarship and the committee was interviewing me, one of the questions they asked-, they first started by saying, ‘Cecil Rhodes, in his will, said he wanted the people who get this scholarship to be people who would fight the world’s fight,’ and then, they said, ‘What’s the world’s fight for you?’ And at the time – I was 22 years old – I don’t remember how I answered, exactly, but that question really stuck with me for a couple of reasons. One is that, in the interview process itself, I ended up being clearly the last person they chose, and I can tell that story as well. And then, a couple of the committee members, kind of, came to me afterwards and said, ‘Look, do us proud,’ like, ‘Make us right.’ So, the combination of them asking me, ‘What’s the world’s fight?’ and then having actually been selected and being the last of the four candidates picked, and then that encouragement from the committee members, just really stuck with me. So, that question just stuck with me and I thought, ‘You know what, I’m going to go to Oxford, but how am I going to fight the world’s fight? What is it? How am I going to make this contribution? How am I going to make the world a better place?’ And so, I eventually arrived at doing that in healthcare, but I think it was the question that so crystallised my focus on trying to figure out the answer to it that helped get me there, and I think helped get me there faster [30:00] than I might have otherwise.

JBG: And you alluded to another story that gave you insight about the selection order. Would you mind expanding on that?

PM: Oh, sure. Well, they’ve changed the geographies and the structure of it since then, but at the time, there were these geographical regions. So, you’d have to qualify within your state, and then once you did that, each state would send two candidates, and our region was in Seattle. There were seven states, so there were 14 candidates that were getting interviewed by a committee, and they were going to choose four of the 14 to get Rhodes Scholarships. So, there were eight regions countrywide, you know, four in each region, 32 in total. So, they set up this schedule where each of the 14 people would get interviewed by the committee and then, at the end of that, everyone had to come back and sit in a waiting room while the committee deliberated, and the committee had the right to bring people back in and ask more questions, if they wanted to. And they were scheduled to finish up, I think, at six o’clock or something like that, and then, we were all going to go and have drinks and dinner, you know, this whole thing.

So, they brought us back, and we were sitting in the waiting room, and we were waiting for a really long time. I mean, it must have been close to two hours, and they were clearly deliberating, deliberating, and then one of the committee members came out and asked one of the candidates to come back in and get interviewed again. So, he went in and got interviewed again for a while, and then he came out and sat down, and shortly after he’d finished that interview, he actually started crying, and, just, my heart went out to him, and everyone was, sort of, sitting there, nobody knew what to say, and I started talking about loud to the whole group. I said, ‘I know this is important, but this is just wrong. It shouldn’t be like this. They should be able to figure this out and do this more quickly and do it in a way that’s more humane.’ I can’t remember exactly what words came out of my mouth, but I started going off about, ‘This doesn’t feel right to me,’ and then, the door opened, and one of the committee members came out, and they looked at me, and they said, ‘Come on in, we’ve got more questions for you.’

So, I went back in and they interviewed me for 10 or 15 minutes, and then I came out and sat back down, and then, a few minutes later, they asked the same guy that they asked to come back in originally to come back in again. So, he had his original interview and then he got called back twice. He went back in again, got interviewed for a little while, came back out, they deliberated and then they brought us together, like, two hours late for dinner. It was, like, eight p.m. or something like that. We were all starving, right? And they announced the winners, and I was one of them, and the other gentleman was not. So, that was the time when I was, like, ‘Well, it’s pretty obvious. They picked three people, and then they were struggling and debating about the fourth,’ and there’s just no other explanation I can come up with for why we were the only ones that were brought in for extra interviews. And, you know, my heart went out to him, because it was obviously really difficult for him, given how he reacted, but at the same time it was, you know, incredibly exciting for me. And then after that announcement, and at the dinner, that’s when I had a couple of committee members come to me and say, ‘Do us proud.’

JBG: So, you arrived in Oxford in the fall of 1989. Is that right?

PM: Yes, that’s right.

JBG: Had you been to Oxford before?

PM: No. I had not been to the UK, not been to Oxford. This was my first experience in that country.

JBG: Right. And did you live in college your first year?

PM: Yes. In fact, I lived in college the first year, and then I lived in an apartment the second year.

JBG: And what was that experience like, living in college?

PM: Well, to me, there’s so much about it that is different and fascinating. So, first of all, it’s just the buildings are so historic. I mean, it’s almost like you’re walking into some version of a castle, and there’s a, kind of, romantic feel to that, but then there’s also the practical, like, ‘Oh!’ They didn’t really have a lot of modern fixtures there. So, it was draughty. I mean, it was fine. It worked out just fine. But the food was really not good at all. I’m sure they’ve improved dramatically, but the fact that there was so much good ethnic food – particularly Indian food – available at reasonable prices, I think saved me, my first year there, because I was having to eat on campus and the pickings were slim. You know, I don’t know why the English came up with such unappetising names for some of these dishes. Like, ‘Toad in the hole,’ would be for dinner, and I’m thinking, ‘Can’t you come up with some better name that sounds more appealing?’

No, but there was just that quality of walking into these beautiful, pristine quads with these historic, ancient walls and buildings that really created quite a different feel to any environment that I’d been in before. Of course, the downside is old facilities, and you’ve got the challenges that I mentioned before. And culturally, it’s a combination of English culture, but also this academic culture: far more formal than anything that I had experienced before, and I would say there was just a high degree of consciousness around being proper. You know, there’s a proper way to do things. There’s almost always a proper way to do things, a proper way to interact, and having grown up in North Dakota and played on a hockey team, to me, I was much more informal in the way I engaged.

And I’d say the other thing that ended up happening is-, I grew up, and when I was in college, I would get a lot of teasing about my accent, because I sounded a lot like the characters in Fargo, and at any point, I can go back to, ‘Oh, yah, you betcha. That’s quite the deal there,’ but when I got to Oxford, just, everyone around me, there was such precise diction, from the students and from the professors and from everyone else, that I ended up being, I would say, a little more formal and precise in my diction and in my communication as a result of that, and didn’t even realise it, but then, when I showed up in New York after being in Oxford, people really didn’t talk to me about my accent anymore, and I don’t think they noticed me having an accent. Every once in a while, I might say, ‘Soorry,’ and they would say, ‘Oh, I can hear that. I can hear that long “o”.’ But other than that, that’s another thing that changed, that I think was less obvious and not expected. Kind of, living on campus and living in that environment.

JBG: And what did you read at Oxford?

PM: Philosophy, Politics and Economics.

JBG: And it sounds like, prior to Oxford, you were still thinking about potentially politics, potentially academia. Is that still where your focus was when you were in Oxford?

PM: It was when I first got there, and then it did start to shift for me, in a couple of ways. One is that I actually found as I was studying more advanced in each topic, economics and politics, that it was becoming less interesting and less fun, in part because it wasn’t always that practical. So, I remember at one point, one of my essays in tutorials was focused on poverty, in my economics class, and these readings were, you know, these two academics who were going back and forth, debating the definition of poverty and where that line should be drawn. And it got really technical and deep, and it’s not like I didn’t understand it. I did. I just thought, ‘What a waste of time. We know there is poverty in the world. What are you doing to solve it? Like, why are you spending all of this energy-?’ They had literally each written two papers, going back and forth and debating and rebutting, and we had to read through those things and then write an essay on it and discuss it. But we all know there’s poverty out there? Like, what are we going to do to fix it? The line’s here? Or the line’s here? I mean, why are we spending so much energy on where the line is, [40:00] as opposed to how we’re going to help people?

And so, what I found was, that sense of wanting to contribute, make a difference, my worry was that if you get pulled into the academic sphere more, you could get lost on the way-, Why are we studying this stuff? We’re studying this stuff to try to make the world a better place, and you can get distracted by going down these rabbit holes, like this question about defining poverty as opposed to doing something about it and coming up with policies and approaches to do something about it. So, I started to get a little disenchanted with the notion that getting more education was really going to help me solve the world’s problems, number one.

And then, the second thing: I started to think a little bit about, ‘What would life really be like as a politician?’ And it didn’t completely lose its appeal, but the fact of the matter is, whether or not you got to play that role depended on whether you won elections, which you couldn’t guarantee one way or the other. And so, you would need to make a living doing something, right? You couldn’t just count on being paid to be an elected official, because you’d have to get elected to do that, and sometimes it happens, and sometimes it doesn’t. So, there was always a need to do that, but I would say the other part of it is, you have to spend a whole lot of time asking other people for money. You know, you don’t just get to sit down and solve the world’s problems. In order to get the right to solve the world’s problems, you’ve got to go fundraise and campaign and win elections, and I felt like I could do that, but those things weren’t nearly as appealing as trying to solve the world’s problems, and so, I thought, ‘Huh. I’m not going to eliminate it as a possibility. It still has its appeal,’ but I felt like there might be something out there where I could spend a much higher percentage of my time just focusing on actually solving problems, and less on doing the things that would put me in a position to allow me to solve the problems.

So, I started to tilt away from that, and to me, one of the parts of economics I liked-, I did like both macro- and microeconomics, but microeconomics is really just business. I mean, it’s just business finance. I don’t think that economists would necessarily agree with me, but for me, it really was just about business finance. And so, McKinsey had this programme where they would go on campus and anyone who was a Rhodes Scholar or had academic qualifications, they would invite you to an interview. And so, they were recruiting at Oxford, and I had some friends from the year before – like, they were second-years when I was first-year, went into the programme, and really raved about it. And so, I thought, ‘Huh, well, I’ll give this a try,’ and I did some interviews, and they had all these business cases which they’d put out there, which I thought were fascinating and I loved them, and I got to the end of the second round of interviews, and I said, ‘Is this what you do? I mean, is this what you do?’ and they said, ‘Yes, this is what we do.’ I thought, ‘Well, I could learn a lot doing that. I mean, it’s like applied microeconomics in a business environment, and you’re doing it for lots of different businesses, so it would be a great way to get introduced to this, and I’d started to make a living and get some exposure, and you don’t have to choose a particular profession or a particular industry right now.’ So, it got very appealing, and as it turns out, the economy was softening kind of bit, and I got to the final round with McKinsey, but they ended up not making any offers in their Chicago office, which is where I was interviewing. So, I then put my resume together and interviewed in a couple of different other places and took a job with Booz Allen Hamilton as a result of that. So, that is what got me into consulting.

JBG: And that role brought you to New York?

PM: Yes. That was in New York, so I went from-, you know, when I finished Colorado College, I actually spent a year studying Russian to, kind of, master the Russian language, and six months of that, I spent in Moscow, which was a pretty fascinating time, because Gorbachev was the leader, and I left there, I want to say, six months before the Iron Curtain fell, and the Berlin Wall and everything. So there was glasnost and perestroika, and there were, kind of, really a lot of things changing in the world. So, it was great to get to a level of mastery with that language, but also just to experience that part of the world at that time. So, I went from Colorado College to Moscow, to Oxford for a couple of years, and then to New York. And it was just, living in such very different environments, the then Soviet Union and then the UK and Oxford, it didn’t feel like nearly as much of a culture shock to go to New York and it would have been, I think, if I had just gone straight from college, because North Dakota and Colorado are very different than Manhattan.

JBG: And the consulting work that you were doing at that time, did you find it to be similar to the kind of exercises you had done in the recruiting?

PM: Yes, I did. I think they represented it well. I mean, there’s a lot more work and volume of work to go into it. They would condense these business cases down to something you could discuss in the interview, whereas sometimes, it would take three to six months to get there in real life. But it was very much like that, and I enjoyed that part of it. I learned a ton. They had me originally really starting out focused on financial services, so I was doing a lot of retail banking, credit cards. I worked on stock market tech work and retail branch banking, that kind of thing.

So, I was doing a lot in that space my first couple of years. There was a group that had been doing just emerging work in the healthcare space, in particular, traditional healthcare insurance plans were trying to figure out what do about these things called ‘Health maintenance organizations,’ which are often now referred to as HMOs today, because they were just getting started and it was a bit of a disruptive force at that point. So, they weren’t quite sure what to do and what had been, think, for a long time a very sleepy industry was starting to wake up to the fact that they might have to do things differently.

So, this small group of consultants within our company had been starting to work on that, and they asked if I was interested in joining, and they shared some of the materials, and then it really clicked in. The whole ‘Fighting the world’s fight’ question clicked in, because first of all, this system is really messed up. It’s not organised and functioning in a way that it should, and we’re all mortal, so at some point, if you haven’t already used the healthcare system, you will. It’s just a guarantee, pretty much, in life, that that’s going to be the case. So, if you can actually change the system, make it better, you’re clearly going to be impacting lives-, like, everybody’s life to some degree, you would be able to have an influence on, and so, it felt like, to try to take a system that is not functioning anywhere near the level that it needs to and turn it into one that – as we describe it at Blue Shield of California – is worthy of our family and friends and sustainably affordable for everyone became a calling. And I wasn’t using those words at the time. I think we developed and refined those words over time, but that feeling really came out from that discovery process. And so, I said, ‘Absolutely. I want to do this. I want to work with you. I want to be a part of this,’ and then, I spent my last two years at Booz Allen Hamilton just working on [50:00] healthcare, health insurance-related work, and just have never looked back.

JBG: That’s wonderful. And so, this would be in the early to mid 1990s. Is that right?

PM: Yes. I worked at Booz from 1991 to early 1995. It was about four years in total.

JBG: Wonderful. And then from there, you made a transition to the West Coast, right?

PM: I did. I met my now wife in New York. She had worked at Booz Allen Hamilton after she graduated college, for two years. Then she went and got her master’s of business degree at Stanford, and then she went from Stanford back to Booz. She was coming from Stanford back to Booz Allen in New York when I was coming from Oxford to Booz, and so, we met there, and we got engaged in the summer of 1994, and we both knew that we didn’t want to live in New York forever. We had talked about that already. And so, the night we got engaged, we were sitting at dinner and I said, ‘Well, if we don’t want to live in New York, we now have this life together.’ In true consulting form, I said, ‘Well, why don’t you write down your top three places you want to live, and I’ll write down the top three places I want to live, and then we’ll, like, compare, and we’ll figure this out over dinner.’ So, I took out, like, a napkin and a pen and I was thinking, I was looking, and she wasn’t writing anything down. She was just sitting there, looking around, and I said, ‘Why aren’t you writing anything down?’ and she said, ‘Well, there’s only one place in the world to live. It’s the San Francisco Bay area.’ She had been to Stanford, absolutely loved it. That’s where she wanted to live. I had never been there. I had actually made one connecting flight and spent, maybe, two hours at the San Francisco airport once.

JBG: Not San Francisco at its finest.

PM: Other than seeing the Golden Gate Bridge as I was landing and taking off, I had no exposure to San Francisco. So, I said, ‘Well, we are engaged, and apparently, that’s where we’re living, so I should probably visit.’ So, we went, paid a visit, loved it, and then we picked up and we moved, late 1994, early 1995, to the San Francisco Bay area, and that’s also when I made the transition-, I felt, at that point, I really wanted to own the results more, and was less interested in, kind of, a mercenary approach, you know, kind of, gun for hire, strategist for other companies. I really wanted to, sort of, get into a company and try to drive some change and some performance and be able to own those and live with those. So, that was the time we made a series of transitions. We moved out, we bought a house, we got married, we both changed jobs, obviously, because we weren’t going to be in the same jobs in the San Francisco area versus New York. So, that was a really big transition period, the summer of 1994 to the summer of 1995.

JBG: And when you say that you changed jobs during that period, was that when you first joined the Blue Shield of California team?

PM: Yes. I looked around, I have a couple of different offers, and I just really liked the Blue Shield of California team and approach and where they were and what they were trying to do. So, in 1995, I joined Blue Shield of California.

JBG: And I’m curious what your work looked like during those first couple of years.

PM: Well, I got hired as Director of Product, and what they were trying to do is-, I think Blue Shield of California was relatively late getting to this HMO, managed care model that had spread quite broadly, including in California itself. They had really seen themselves and conducted themselves as a traditional insurer, and they had just, about a year and a half before I got there, brought in a new CEO who had come from Kaiser, and Kaiser, of course, owns physician groups and hospitals and really has a very, very integrated care, hands-on care delivery model that’s almost exclusively HMO-based. And so, he came in and, you know, completely revamped the executive team, brought in a chief operating officer and a chief marketing officer. It was the chief marketing officer that hired me. And they said, ‘Look, this is like a startup with money and market share. We have a brand, we have a company, we have customers, but we’re here to reinvent and remake it, and we’d like you to help, and we’d like you to help starting with, like, how you design different products to do that.’ So, I focused, actually, on our HMO and our HMO products and came out with a number of innovations around that, that helped us drive some significant organic growth. We reversed our decline. So, that was, kind of, what I was doing in my first few years at Blue Shield.

JBG: And I’d love to hear a little bit, Paul, about what inspired you to start thinking about MyWayHealth.

PM: Yes. Well, I had a very strong sense early on, as I said, when I was at Booz and reading those documents, that the system was not functioning well. It wasn’t set up the way that it needed to be set up to deliver care that’s worthy of our family and friends and sustainably affordable. So, I felt as though it was important to be trying to drive change in that system to get it to where it could be. That required a level of vision and foresight and courage and entrepreneurial and creative spirit, and what I was noticing in my time at Blue Shield was that, while we were doing some innovative and creative things – in fact, I would say, more innovative and creative things than most of our competition was – it wasn’t fundamental structural, systemic reform. It wasn’t truly reinventing the system.

And so, I started to get the feeling that, like, my ambitions for transformation and change in the healthcare system just weren’t matching up to the ambitions of the organisation, and that was starting to frustrate me a bit. And so, I thought, ‘Well, look, if I can’t convince Blue Shield to really get to the level of aggressiveness on that, that I would like to get to, then, it’s the San Francisco Bay area, and there are all these dotcoms starting up. Like, we can just start a company and go do it.’ But I had never gone out and done this. I’d never raised money before. So, I started to look around and talk to different people about this, about different possibilities, and then I got together with a couple of partners, and we started MyWayHealth, and the idea was, ‘This is the way a health plan ought to be run, in my mind, to really fundamentally change, transform, restructure the health plan, and make it much more centred around the person, centred around the patient, or the member,’ which is why we named it MyWayHealth. It’s this idea of, you know, it’s the way you want it. It should work for you and around you.

JBG: And so, MyWayHealth launched, and what inspired you to start thinking about a transition back to Blue Shield of California?

PM: Well, a couple of things happened along the way. So, one is, we started the company just before the dotcom bubble burst. So, we raised money, and I couldn’t believe it. It was, kind of, a mania. It was back in the times when it was, like, ‘puppychow.com is going public!’ People would just put ‘.com’ at the end of something, and they’d raise all this money, and they’d go public before they had any kind of revenue or income. I don’t know if you remember it, but it was pretty manic back then: ‘The internet, the internet, the internet.’ And so, fortunately, my partners and I looked at his and said, ‘You know, this is not going to last forever. We need to come up with an actual business plan that’s got revenue and income attached to it.’

So, we were getting offered more money, but we didn’t take it. We just took a modest amount of money to start and worked on it, and we came up with a business plan that we felt really good about, and then we were, like, ‘Okay, we’re ready to go out and raise money again,’ and then the dotcom bubble just burst. All of these companies collapsed, the stock market dropped precipitously, and a lot of these venture capitalists that were just gung-ho just stopped answering phone calls. And so, we had gotten to the point where we had a business case. We literally had a couple of customers that had committed to buying a product, but on the contingency that we raised money so we could build the product [1:00:00] so we could get to revenue, but we just couldn’t get financing, because the market just turned. It completely turned on a dime.

But in the process, we had talked about selling our company to-, there were a couple of other startups in a similar space, and we had discussed it with them, and one of them, Definity Health, which was mature, had raised more money, actually had revenue and customers. Because they couldn’t raise money, they were, like, ‘We can’t buy your company,’ and when we closed it down, they were impressed enough by me that they asked me to come work for them. So, I went to work for Definity Health, which was just another early stage company. It eventually sold itself to UnitedHealthcare a couple of years later. But they brought me in and I was working with them, but they were headquartered in the Twin Cities, in Minneapolis, so I was trying to help them in California, but having to travel, increasingly, to the Twin Cities, and, you know, we were raising a family at the time too, or at least starting. My son was born and my daughter eventually came along a little bit later. I didn’t really want to be on the road that much and so, it just was serendipity that Blue Shield of California had won a big piece of the business from CalPERS, which was the California State government account, and they needed a senior executive to run that.

So, they called me right when I was thinking, ‘You know, as much as I love this entrepreneurial work, it would nice to not be on the road so much.’ The other thing I discovered in my experience was, as much as it was great to move really quickly, make decisions really quickly, in a very dynamic environment, at one point in my time with Definity, we had a customer in California who said, ‘We’re having this problem with this provider in California. Could you try to call them and see if you can’t work it out?’ And I said, ‘Sure, happy to do that. So, I reached out, emails, calls, and I never got a response. Just kept pinging them, and never got a response. And what I realised was, ‘We’re tiny. Like, we have almost no membership in California. They’re dealing with a dozen plus different health plans. Like, until we get to a certain size of their wallet, their revenue, I’m not even going to get the time of day from them,’ let alone going to them and saying, ‘Hey, let’s create new payment models and let’s create innovative ways to make the system centred around the patient.’ So, one of the other realisations that I had was, yes, you can move quickly in a context. You can move quickly as a startup on making decisions and being dynamic and making that grow, but you’re not going to move the system quickly unless you have market share, local market share with those providers, because you’re just not going to get their attention, and you really can’t change the system unless you change their behaviour. You’re going to have to partner with them to do that, and they just have zero interest in partnering with you if you’re a speck of dust on the table. You’re not important enough to them.

So, I realised, yes, we could move really quickly, make a bunch of decisions, but it would probably be four or five years of growing rapidly before I would have enough volume to get enough attention just to have a conversation, and they’re not about to change the business model and turn it upside down for a startup. So, the combination of not wanting to travel that much and then realising, ‘You know, my passion is around changing the system. To change the system, you actually need to be creative and innovative, but inside a company that has money and market share. That is the right recipe for success.’ So, both those realisations came about the same time that this CalPERS development happened at Blue Shield of California. So, they called me and said, ‘We know you, we’d love for you to do this,’ and it didn’t take very long for us to work out the details and for me to say, ‘Yes.’

JBG: Great. And that was 2002?

PM: That was 2002. I left Blue Shield of California in January of 2000 and I came back in May of 2002.

JBG: Great. And what did your journey at Blue Shield of California look like after you rejoined the team?

PM: Yes. I mean, I was running the CalPERS account and then I had a conversation, probably a year or so after I returned, maybe a couple of years after I returned, with the then CEO, and he asked me, you know, whether I might be interested in his job some day, and I said, ‘Sure. That would be interesting.’ And he said, ‘Well, I think you could do it. You’re not ready to do it now, but I think you could do it.’ So, from that point on, you know, as things opened up, as opportunities were created, I just got promoted. They kept giving me more things to do, and so, I wasn’t just managing CalPERS, I was managing all large employers at one point. And then, they made me chief operating officer and started to give me other pieces of the business, like the provider contracting and back-office operations like customer services claims processing, and then, eventually, the clinical team came to me as well. Marketing and sales was already with me. So, I got a chance to basically manage all the functions of a health plan, and then, I was chief operating office for four years, and then, our then CEO – he was CEO at the plan for 13 years – he decided to retire, and the board decided to give me the job, which I’m very grateful for.

JBG: Wonderful. You now, Paul, have been at Blue Shield of California for over two decades.

PM: Yes. Almost three, actually.

JBG: Yes.

PM: Let’s put three decades into two.

JBG: And you have had the opportunity to lead the organisation, and I imagine this is difficult to condense down, but I’m curious to know what experiences stand out as most meaningful when you reflect on that time.

PM: Well, I feel like I’ve had a number of learning experiences along the way, but I’d say one of the things that stood out maybe earlier in my career is that I was usually in my head first about what needed to be done and how it needed to be done, and what I mean by that is, ‘What’s the strategy? What’s the vision? How do we solve this problem? How do we organise the system differently?’ And, you know, that’s what you also got trained to do as a consultant as well. That was my natural inclination if something came up, was to go straight to my head and say, ‘Okay, let’s figure out how to take advantage of this opportunity or solve this problem,’ and not to start with people, not to start with relating to other people, not to start with your heart.

And it’s clear, I think, from all these conversations, that the source of my energy and my urgency and this passion is in my heart, it’s in this desire to create this system that’s worthy of our family and friends and sustainably affordable. But I wouldn’t express that or show that. It was, like, ‘Yes, well, of course that’s what’s going on. Now, let’s get to solving this problem.’ And so, I started to get feedback – and not always positive feedback – about how that wasn’t going over so well, and how important it is to win people over, win hearts and minds, and connect with people along the way, to show yourself, you know, in your full light, as a complete human, and have that human connection with people, and how foundational that is to being an effective leader and to making a difference in the world. And I’d say, by way of example, when I first started back in 1995, I had a group of maybe three to five people. It was a very small team, and we were doing mostly marketing type product formation and design. We weren’t doing anything operational and major. And so, like, I knew the people. I was totally in touch with all the work. I could do quality control of the work. And then, the first promotion I got, they said, ‘Well, take on the operations of the products as well, not just the design and the marketing of them,’ and I said, ‘Great.’

So, I went from having, I don’t know, four or five people, to having 50 [1:10:00], and at first, I thought, ‘Great.’ I just was a whirlwind. I just was running around and I’d go from meeting to meeting and read through all of the materials and, you know, make sure the work was at the standard that I wanted, and I was just pushing and driving and getting good results, and my boss loved it. And then, I think, six to nine months into my tenure, we did one of those leadership surveys. There are all kinds of different structures, but they have different scores for different categories. So, I got the feedback back, and they did it for my direct reports-, not just my direct reports, but they split it out: like, your director reports, your peers, your boss, your self-assessment. And for my direct reports, or for the people on my team, I ended up scoring four on the category of, I think, team-building, or something along those lines, which wouldn’t have been so bad, except that the scale was from one to 100.

So, to see that, it was just, like, ‘Oh, my god!’ It was like getting smacked right between the eyes, and I ended up talking to a couple of people afterwards, and they said, ‘It’s like working for a robot. You show up, you never ask me how I’m doing, you never check in on anything that’s going on with me personally. You just show up and you go straight through the agenda and you drive through it and it’s, like, I don’t even know who you are. I don’t have any sense that you care about me or my professional goals or my personal life or any of those things.’ So, people were basically sending a message, like, ‘This is not working for me,’ and, you know, your first natural reaction to something like that is to say, ‘Well, I just need new people who appreciate me more. I’m clearly smart and doing a lot of really good things and my boss loves me, so, they’re just going to have to figure out how to live with me.’ And I just processed for a little while and thought, ‘No, these are smart, good people, and this is on me. I’ve got to figure out how I need to shift and change.’ And so, a lot of what has happened to me over time traces back to that, which is, instinctively, I tend to want to go straight to problem-solving and go straight to the head and the content of the business question, and I’m much better now about slowing down, checking in, trying to win hearts and minds and also, just to get and stay connected with people. I am not saying I’m brilliant at it, but I’m way better than I was when I got a four.

JBG: Thank you for sharing that, Paul. It’s really appreciated. So, in addition to your role at Blue Shield of California and your leadership there, you have also helped your state to navigate through a global pandemic. We’re recording this conversation in 2024, not too far on the heels of when Covid first came upon us, and I was wondering if you would mind sharing about that experience.

PM: Sure. I mean, first of all, I remember the moment when I realised this was, like, a global pandemic and we were going to have to deal with it. Because, for a while, I thought, ‘Well, maybe it’s in China, and maybe it will stay there,’ and then it was, like, ‘Oh, there’s a case reported in the United States,’ but the small number of cases that were identified and reported were people who had, like, been to China or something, and then travelled back. And I remember, it was in March, and over the weekend they said they found a Covid case, someone in Washington State that had never left the state, never been on a plane or been to China, and lived, like, an hour and a half away from Seattle, where people had been travelling and cases had come in, and I thought, ‘Oh, man, this thing is-, there’s just no way that’s the only case.’ There was no direct connection. They hadn’t been in contact with somebody who had been to China. Like, they had not had one-to-one. There was no way to trace how this person got it, and then I knew, immediately, this was here. There were a lot of cases, way more cases than we thought. It was spreading way faster than we thought. I mean, I didn’t know we were going to shut things down, but it was really clear-, I said to the team-, I came back in, because we had this big, 600-person session set up for, like, a week later, and I came in and said, ‘We’re cancelling this.’ They said, ‘Are you sure? Because I’m not sure the news-,’ I said, ‘No. You don’t understand. We cannot do that. This virus is amongst us. There is no doubt in my mind that we have employees that have already contracted it.’ Because the speed at which it had had to move and the transmission of it, to have that case pop up in those circumstances, said that this was a problem.

And it was probably only a week later that we sent everybody home and said, ‘Don’t come into the office.’ So, I just remember that happening, and then I started to think, ‘Wow, this is a big deal and we need to find out where this virus is going. Like, if we’re going to manage it in some way, shape or form, or contain it and deal with it, we need to know who’s got it and where they got it from.’ And I was looking at the statistics, and the State of California, which has almost 40 million inhabitants, was testing about 2000 people a day. And it was, just, like, at that rate, it was going to take 450 years, or something like that. 40 million people. So, it was completely unhelpful to just have that level of testing. So I kept thinking, ‘Well, I’m sure they’re ramping up and it’s getting better,’ but the numbers just were stuck. And I knew people in the governor’s office, including the secretary of health and human services, so I picked up the phone and called him a couple of times and said, you know, ‘We’ve got to do more testing, and how can we help?’ And then eventually, I got a call from someone who worked in the governor’s office who said, ‘Would you be willing to co-chair this Covid testing taskforce, to try to get the testing up, higher volumes and more spread across the entire state?’ And I said, ‘Sure.’ So, I co-chaired it with Dr Charity Dean, who, at the time, was working in the public health department of the State of California. She has since left and started her own company. But she was also the major character in the Michael Lewis book Premonition, and so, you can read a little bit about what we did in that book. It’s actually a well-written book. Most of Michael’s books are. But we ended up co-chairing that taskforce, and it was intense work. I mean, it was seven days a week. I was pretty much eating and sleeping, getting a little exercise, and then just working every day. Saturday looked like Tuesday. Because it felt like we really needed to-, this could save lives, if we could get up the testing done, and within three months, we went from roughly 2000 tests a day to over 100,000 tests a day, set up a network across all 58 counties, and set up enough infrastructure that, you know, by then – we left after three months, but I think by month four or five, there were over 200,000 tests a day. So, we scaled it up rapidly, and it went from, I think California was somewhere between 45th and 50th on Covid testing per capita, to number one or number two.

JBG: Wow.

PM: So, after that, eventually, we got a vaccine, and the state got Covid vaccines. So, that would be in late 2021, I think. Anyway, the same pattern emerged, where the state was just struggling to get vaccines administered and recorded. So, they were, once again, in the statistics, something like 45th or something like that out of 50 states. And so, I started to talk to some of the same people in the governor’s office and they first asked for advice and then, they said, ‘Look, can you come back in and manage the vaccination network? You clearly had experience, just doing it with the testing,’ and I said, ‘Absolutely.’ So, that was, like a five-month-, same kind of drill, like, eat, sleep, figure it out. But by the time we finished, I think California was in the top ten for vaccination performance and, you know, none of this was easy, but it’s one of the things that I find really rewarding about working for a non-profit, mission-driven company like Blue Shield of California, which is, our board was really supportive, our team was really supportive of us just trying to do the right things and help save lives in this worldwide pandemic. Afterwards – I think it got released in 2023 [1:20:00] – there was a study done about the vaccine programme in California and they projected that it saved 20,000 lives.

JBG: Wow.

PM: 20,000 people would have probably lost their lives had we not gotten the vaccines to that many people that quickly. So, when you see something like that, it’s just really rewarding, even though it was an incredibly intense period of time.

JBG: Thank you, Paul. We have a few more minutes left, and I know you spoke a little bit about your wife and shared a tiny bit about your son and daughter, but I was wondering if you would like to expand on your family a bit.

PM: Well, my family, they’re my foundation in life. You know, I’ve got this incredible partner and best friend in my wife Lisa, and we just do everything together. We just enjoy, each evening, having dinner together. So, it’s one of the things I do at work, for example, I say, ‘I know I need to be out, I know I need to travel, I know I need to do evening events, but I think I can do this job effectively with this many evening events.’ So, I actually create a budget, because I’m like, ‘There’s no one else in the world I would rather sit down and have dinner with than my wife.’ So, I just make sure that I do that as much as I can. So, now, we’re empty nesters. My daughter is a junior in college. My son has graduated from college and is doing his thing. But they just mean the world for me, and I would do anything for them.

It’s amazing, that sense of-, sometimes, people talk about sacrificing for others, and I just can’t imagine anything I wouldn’t do for any one of them, Lisa or the kids, and it doesn’t feel like sacrifice. You don’t think about it that way. It’s just, you care so much about them, and it’s so gratifying for them to experience joy and happiness, and you just want that for them so badly that-, yes, I’d just do anything for those folks. And, you know, my sister and brother and parents, I feel the same way. So, that’s really my foundation. It’s one of the things that keeps me grounded. There’s always adversity and challenges in anyone’s job and professional life and I certainly experience that too, but you realise what’s important in life when you, sort of, get back together with them and have those kinds of experiences, the vacations that we’ve had together and just lots of formative experiences. So, yes, thank you for asking. They are the light of my life, for sure, and are more motivation than even this mission that I talked about on the professional side.

JBG: Lovely. Thank you. I would love to close, Paul, with a few questions related to your Scholarship experience, the first being, what impact would you say that the Rhodes Scholarship has had on your life?

PM: I think it’s opened a lot of doors and created a lot of opportunities for me and, as I said earlier, it also helped me sharpen focus on deciding to make my professional life a vocation, and that was a conscious choice that I made, to not just work for a living, but to work for a purpose.

JBG: And then, kind of a related question. So, we just marked the 120th anniversary of the Scholarships last summer, so a natural opportunity to think about the next chapter of the Scholarships, and I would love to know what your hopes for the future of the Rhodes Scholarship would be.

PM: Well, one of my hopes would be that it systematically supports and helps the Scholars with their own journey to answer that question of, ‘What’s the world’s fight?’ Because there is, like, an infinite number of ways you can have a positive impact on the world, and to me, it’s very powerful. I think we all know that if you read about Cecil Rhodes’ life and what he did, there are a lot of really shocking things that you read about, and a number of things that I don’t think any of us would be proud of. But there’s this legacy that has a chance to do great good, and I think it’s opportunity to do great good comes down to, not just giving really smart, talented people a chance at this education and this wonderful opportunity for growth, but to then parlay that into having a positive impact on the world, and that just gets magnified. One of the things I’d love to see happen is just, is there a way to systematically have each Scholar consciously go through those questions, the ones that I did, and have the questions stay with them, and have part of their education and their time at Oxford be spent reflecting on that, and I think that would be really powerful.

JBG: Wonderful. And then, finally – and the answer to the question might be the same, based on what you just shared – but do have any advice or words or wisdom that you would offer to today’s Scholars?