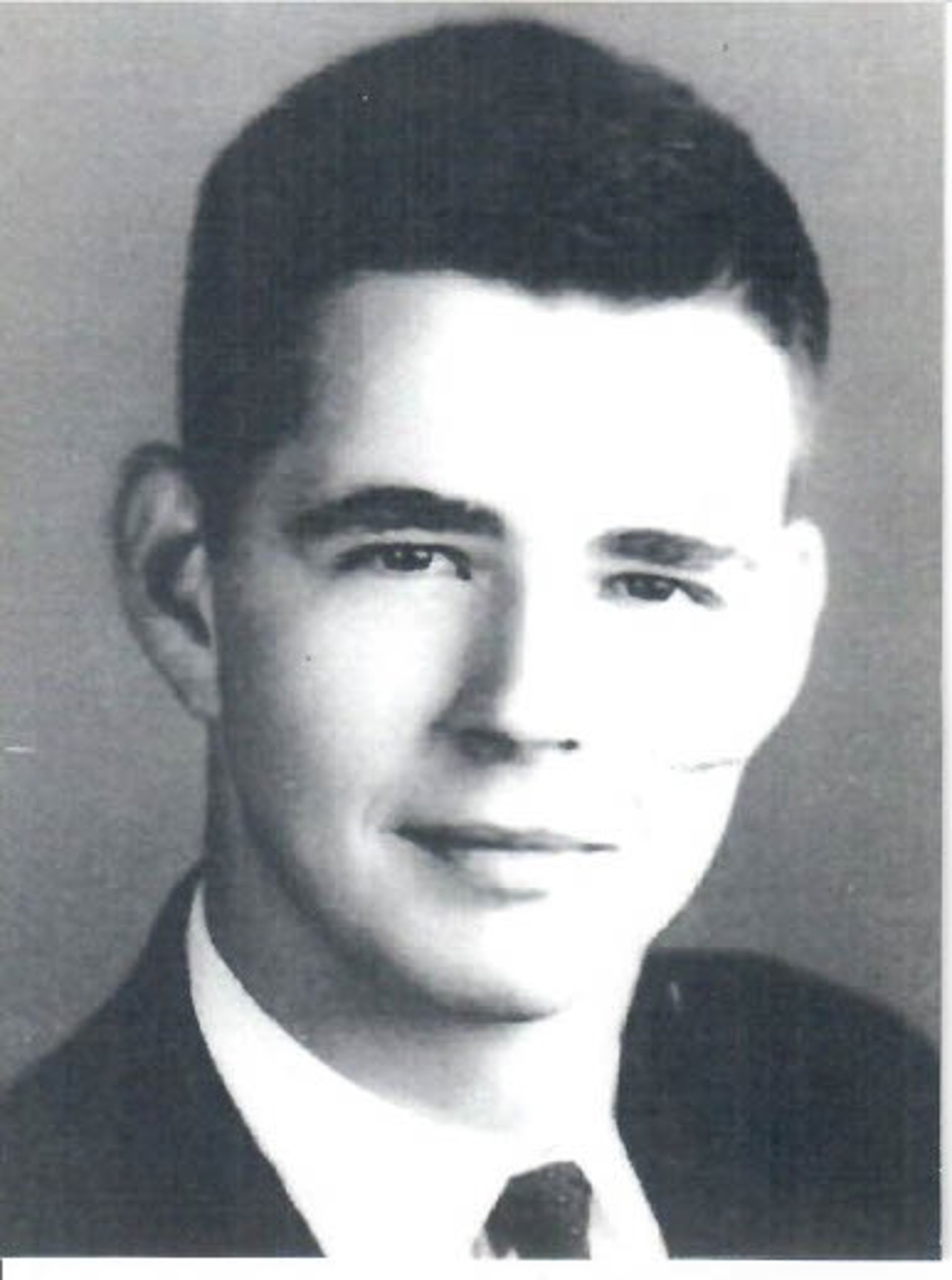

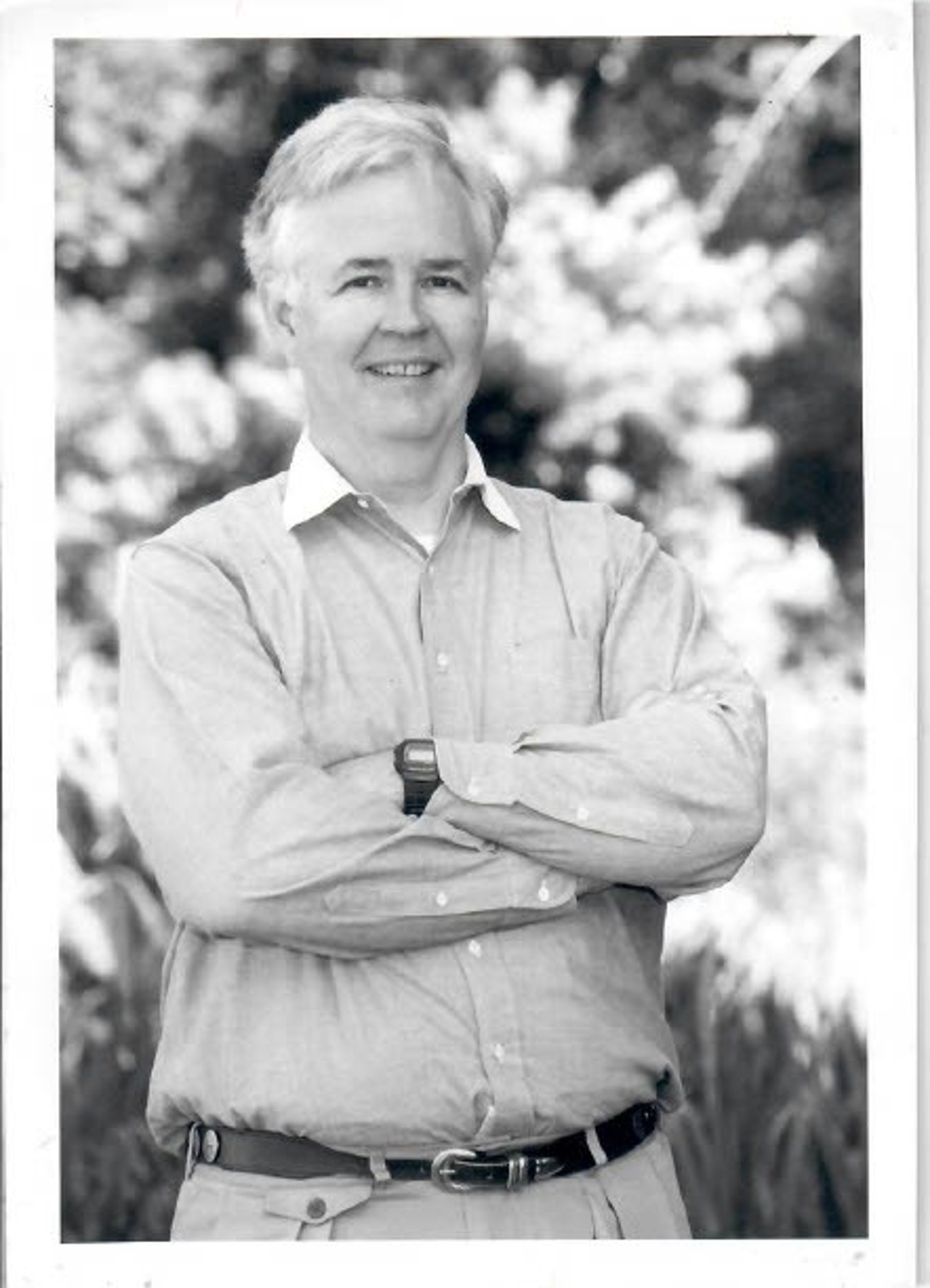

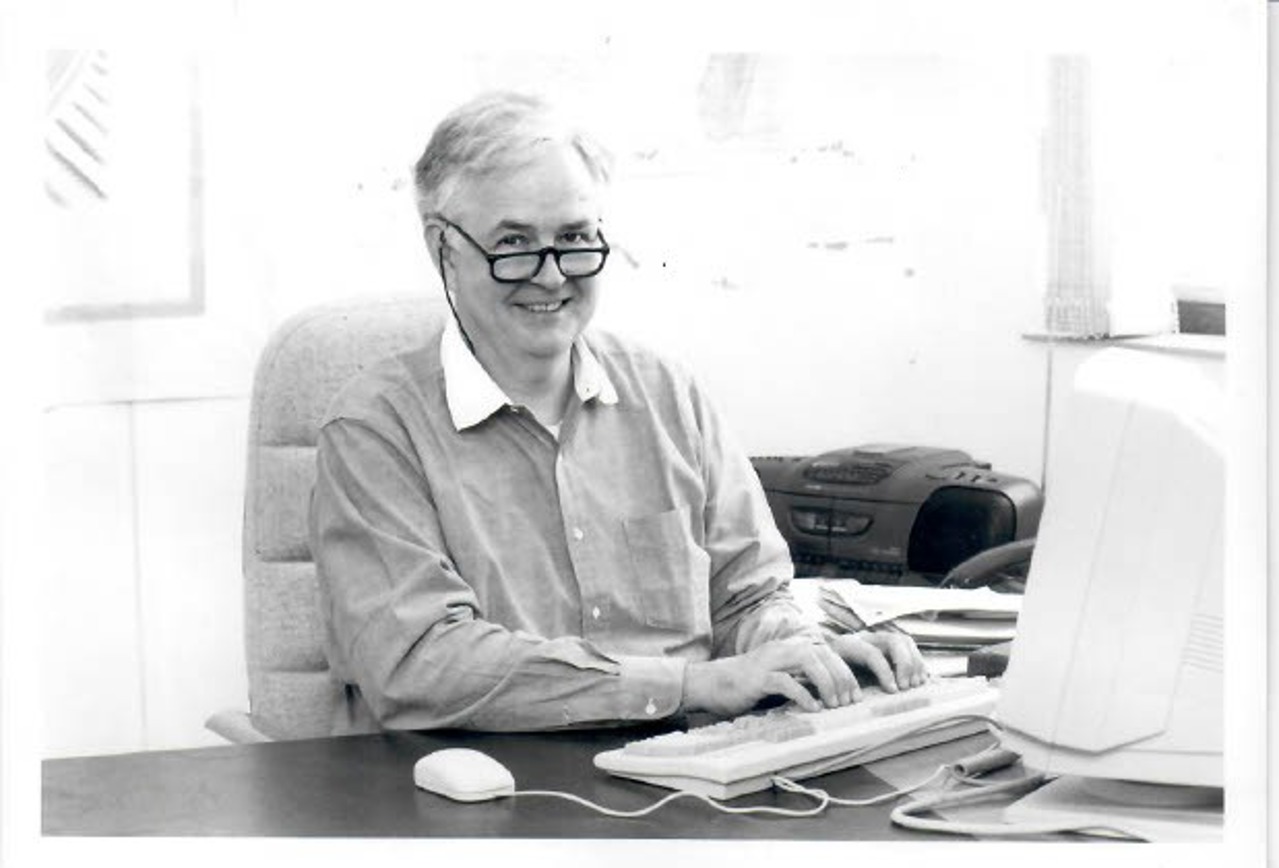

Born in Winston-Salem, North Carolina in 1940, educational activist and former lawyer Norton Tennille now calls Cape Town home. A classicist and linguist by training, he pursued a successful career in environmental law before moving to South Africa and working as a volunteer for SAEP (the South African Education and Environment Project), which provides holistic education for children and youth. This narrative is excerpted from an interview with the Rhodes Trust on August 25, 2023.

Norton Tennille

North Carolina & Balliol 1962

‘I had an infinite amount of curiosity’

I was born just a little over a year before the US was drawn into the Second World War, when Pearl Harbor was bombed. And the country was just coming out of the Great Depression. FDR’s new deal had finally kicked in. So, we were in a transitional period to begin with, and then the war hit, and that just changed everything. My most vivid memories of early childhood are from during the war, when we had blackouts and we had to pull down the shades. Winston-Salem was quite a target, because it manufactured all the cigarettes that were keeping up morale for the soldiers. The first few years, until we got into the 1950s, it was pretty austere.

I was lucky to live in a multigenerational family. Back in those days, that wasn’t unusual, but it was a remarkable opportunity for me, because my great-grandmother had been born in 1862, during the Civil War. So, she had lived into her 80s from that time and I had a relationship with her. She read to me frequently and really encouraged my curiosity and interest in books. I had an infinite amount of curiosity. My great aunt Cassie once said, ‘I think that boy would be happy with his nose in a book all the time.’ It was not said with approval! They thought I was going to become half-baked, because I was just interested in reading and, sort of, following my own internal compass. So, there was always a big effort in my family to make sure that I did not grow up half-baked, that I grew up fully baked.

I had a very strong education, thanks largely to philanthropy. When our local high school burned down, the Richard J. Reynolds family took the decision to spend the money to build as fine a high school as could be designed and built. And alongside that, the high school then hired a truly amazing group of teachers. Those teachers taught my parents, and then they taught me, and they had a tremendous influence on my life. I studied mainly languages, and when I got to the University of North Carolina I placed top in the Latin exam with a perfect score, and top in the English placement test, and second in French, and that indicates the quality of the education I received.

On applying for the Rhodes Scholarship

I wanted to go to Oxford to pursue classical scholarship. I was competitive, and my mother’s influence on me was huge: she had very high expectations, and those drove my aspiration. At North Carolina, I received a newly founded scholarship, The Morehead Scholarship, and I was also part of my university’s honours programme, where we were given the toughest professors and the greatest challenge, and I loved that. I can’t pinpoint exactly when I heard about the Rhodes Scholarship, but I do know that for me, as for so many of that kind of superstar, over-achieving student making straight As, it became a great ambition. In fact, I made it to the regional finals my junior year, but there I fell short. It was a blessing: I was graduating after only three years, and I was in no way ready to go to Oxford. But one of the members of the panel came up to me afterwards and suggested I should reapply the following year. I did, and by that time I was at Harvard, where I’d won a Woodrow Wilson fellowship to study classical philology, and when I applied for the Rhodes Scholarship a second time, I was lucky enough to get it.

‘I was so amazed by the group of people that I was part of’

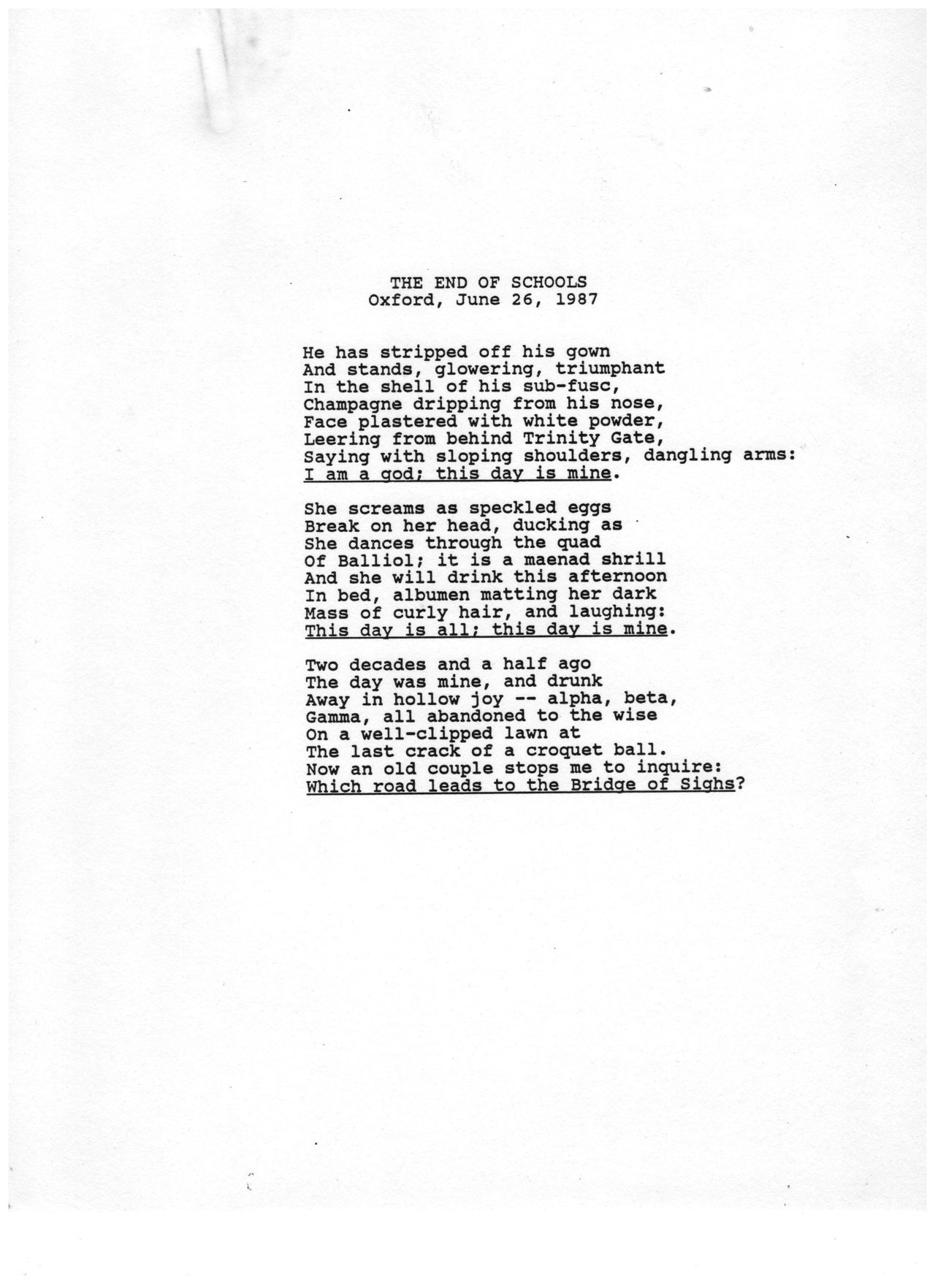

Everything I encountered at that time was something that I didn’t expect. I mean, the first time I walked into Balliol quad, I was frightened or at least intimidated. You know, ‘What is this going to be like? This is an Oxford college.’ But somebody had put a record player up in his window and was playing the Beatles, “She loves you, yeah, yeah, yeah”. So, I perked up at that. And then a guy walked past who was also in my class, dressed all in denim but with his gown casually draped over. And once I began to get to know people, that blew my mind. Not only the other American Rhodes Scholars, but people from all over the world. Balliol was the most international college. I was so amazed by the group of people that I was part of. And I tried all sorts of things: rowing, running for the JCR committee. I must confess, I didn’t spend as much time as I should have reading Plato and Herodotus. At the end of my first year, I changed to PPE. I had already done a year of philosophy, and I enjoyed studying politics and economics too. I really saw them as rounding out my liberal education.

The other feature of Oxford for me was definitely the opportunity to travel. Every vacation, I was off: to Spain, Morocco, Austria, France, Scotland, or Denmark. The summer before Oxford, I decided not to come over on the ‘sailing’ with the other Scholars. I thought, ‘Why should I miss the opportunity to spend a summer in Europe?’ So, I went backpacking, and I spent the entire time in France and Germany, working on my languages as I travelled.

‘Oxford kicked in again’

After Oxford, I decided to go law school, although before that, I had an amazing experience for a summer, as a correspondent in the Time Life bureau in London. Going back to the US and adjusting to law school was fairly difficult. I didn’t really excel there in the way that I had been used to excelling. If you’re accustomed to being at the top of the class and then the world is no longer a classroom, that’s tough. You can begin to lose all the confidence that you’ve developed. For all that, I became a successful lawyer, but after almost 25 years, my heart wasn’t in it. I was actually spending much of my time working with Balliol on US fundraising. So, it was a kick in the pants, but a necessary one, when one of the partners in the law firm came into my office virtually on Christmas Eve of 1993 and said, ‘Norton, the partners have decided it’s time for you to move on.’ And my immediate reaction was, ‘Well, I totally agree.’

I had always done a lot of pro bono work, so I decided I should find a way to spend my entire life working on something of public interest. And this is where Oxford kicked in again. I had gotten to know a South African Rhodes Scholar who had been a human rights lawyer in the struggle against apartheid. I just pumped him for information about South Africa. I’d grown up in the US, in the South, in an apartheid society, and I wanted to get involved in something interracial, to compensate, because I understood I had been a beneficiary of later came to be called white male privilege. I learned from a black student at the University of Cape Town that I had also been a beneficiary of “generational privilege.”

'To thine own self be true'

In early 1994 I flew to Johannesburg, South Africa for a conference, and then on to Cape Town. I remember walking up to the lighthouse at the top of Cape Point, looking out at where the Indian Ocean and the Atlantic Ocean flow together. It was beautiful, and I had an epiphany. It was not a rational decision. It was pure instinct. I decided to stay in South Africa. And not long afterwards, I had another moment of instinct when I met my wife, Jane. In 1994 I founded a non-profit organization which came to be called the South African Education and Environment Project (SAEP). Jane and I worked together at SAEP, which is primarily an educational operation working with children and youth in the black townships. That began almost thirty years ago, Now I’m retired and 83, and in this part of my life, I’ve reached the stage of what Keats called “soul-making”. Everybody said I was crazy to leave the stability of law and come to South Africa. But I took the risk and threw caution to the winds, and it succeeded in ways I could never have foreseen.

If people ask me for advice, my easy answer is, ‘Carpe diem’, ‘Seize the day’. But then, there is the line from Polonius, “To thine own self be true”. Finally, I would say, ‘Individuate’. It’s a term from Jungian psychology that basically means to discover and live the life that fulfils your highest and best self. It’s about personal development and the emergence of a part of you that you may not have realised was there earlier in life. At 83, I think I’ve discovered -- or at least made a lot of progress in discovering -- my highest and best self. And I hope that current Rhodes Scholars can somehow be able to do that over the course of their lives as well.