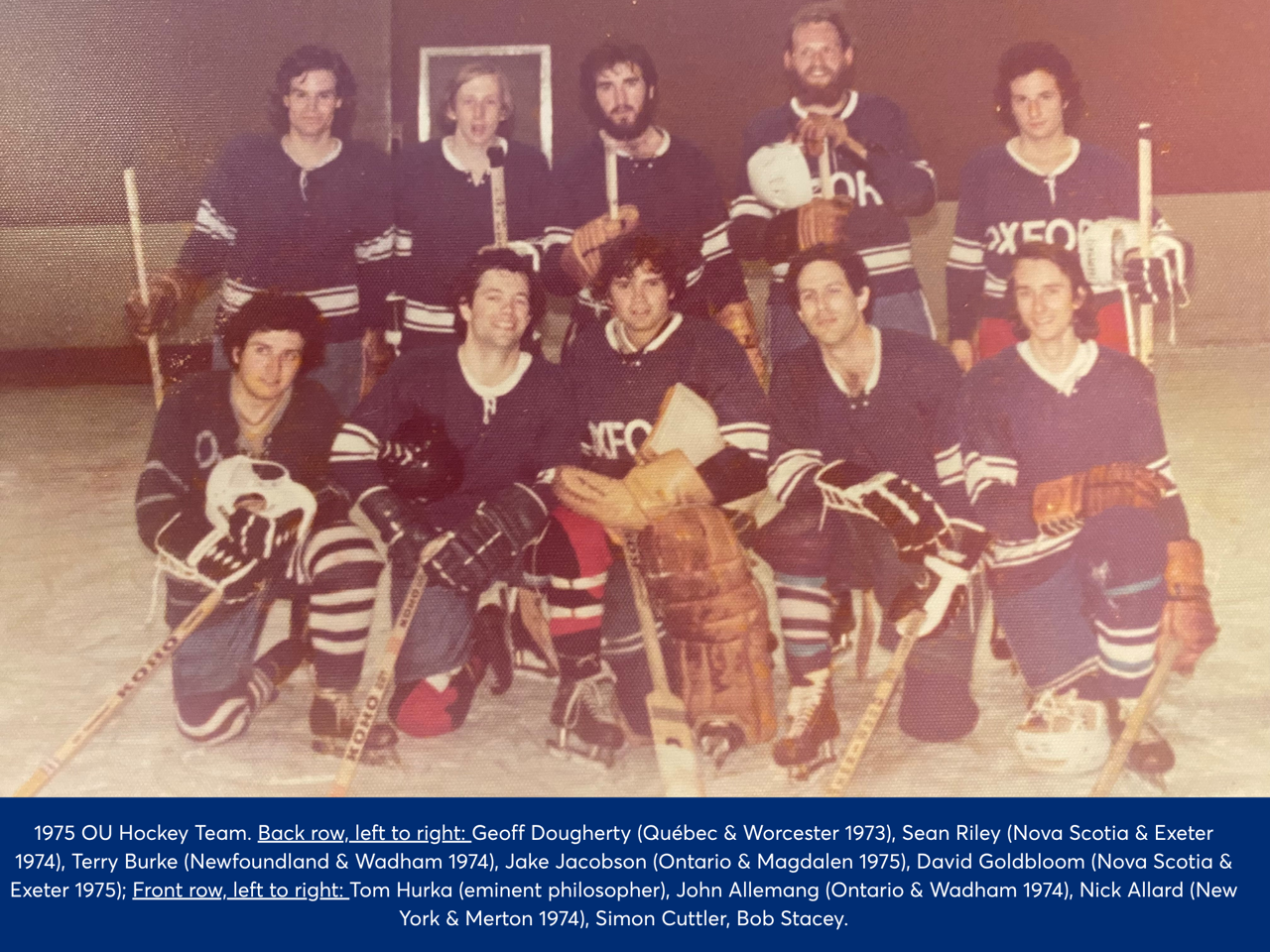

Born in Gettysburg, Pennsylvania in 1952, Nick Allard studied at Princeton before going to Oxford to read for a second undergraduate degree in PPE (philosophy, politics, and economics). After graduating from Yale Law School, he enjoyed a prestigious legal career working in government service and public policy as well as in private practice. Concurrently over all these years he had a foot firmly planted in higher education as a teacher, author, trustee, outside lawyer, alumni leader, and fundraiser. In 2012, Allard moved into higher education full time, serving as Dean and President of Brooklyn Law School until 2018. He is currently the founding Randall C. Berg Dean of the Jacksonville University College of Law. Allard and his wife Marla are dedicated to the support of educational causes, and he has been especially active in his support of the Rhodes Trust, both philanthropically and through service on selection committees, as a Class Leader, and as the North American representative on the Rhodes Trust Global Alumni Advisory Board. He is a Bodley Fellow at Merton College and received the Rhodes Trusts parkin award for service. This narrative is excerpted and edited from interviews with the Rhodes Trust on 5 August 2024 and 4 September 2024.

Nick Allard

New York & Merton 1974

‘A life deeply influenced by two intertwined families’

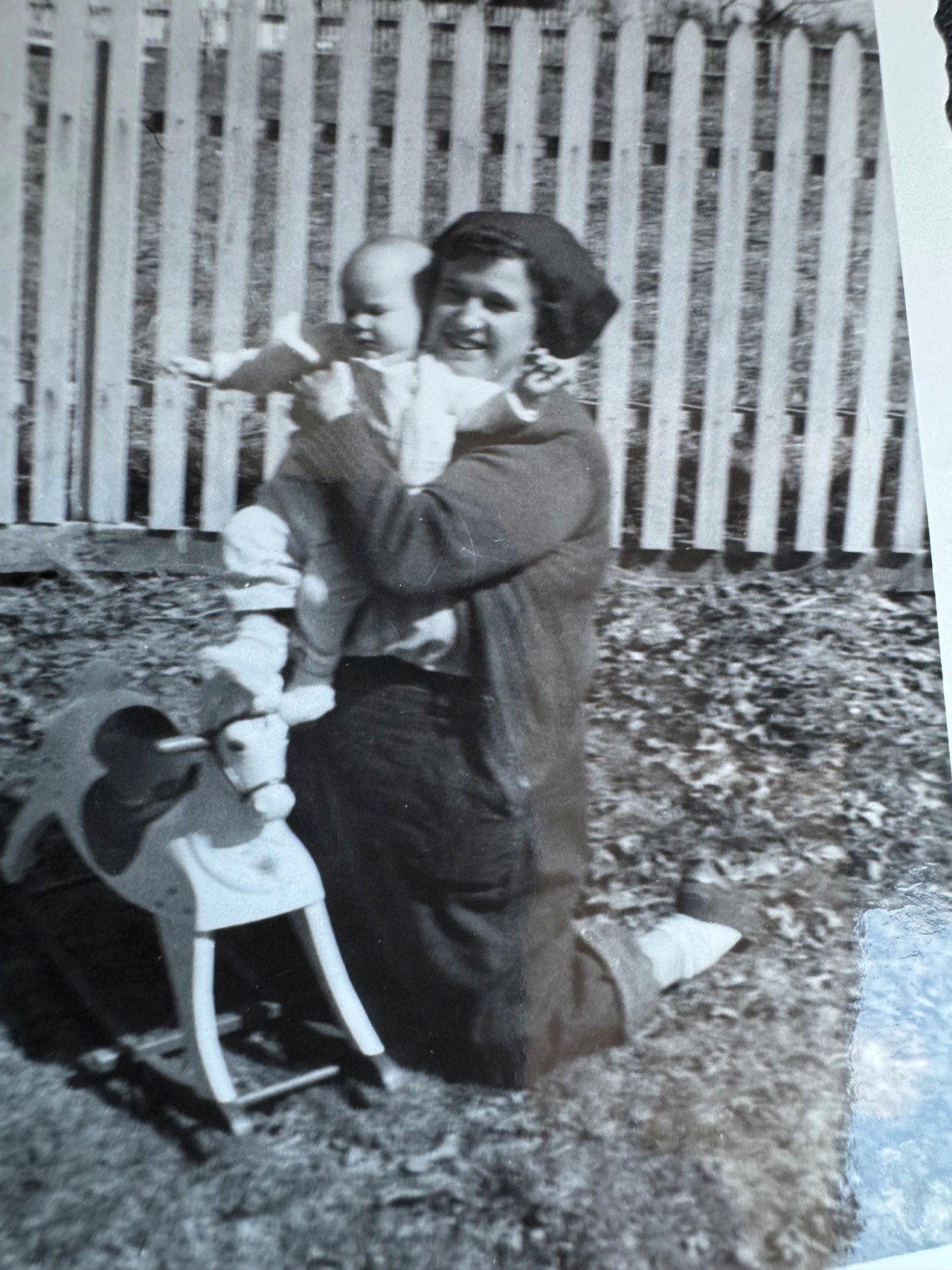

Throughout my life it has been my good fortune to be influenced by two intertwined families. The first, my immediate family, included my mother, my father, my two sisters and two brothers and especially, for example, my maternal grandmother, Edna, who was always a presence in our life as we grew up.. My parents met in college, where they were married, and then I was born the following year before they graduated. After my father started medical school they ran out of money, and Dad had to give up his dreams of a medical career. They moved to New York to live with my grandmother, and not long after that, we all moved to Northport, Long Island. My grandmother was a Navy nurse, and I remember her coming home from her shift at the veterans’ hospital in Northport when all of us were outside playing baseball and she would just join in and play with us, in her nurse’s uniform. One time, she had to go see our family doctor because she broke her hand playing baseball, and he asked, ‘Edna, ow did you break your hand?’ She explained ‘Well, I was playing baseball with the kids.’ He said to her, ‘Edna, aren’t you ashamed of yourself, a woman of your age should know better?’ She quipped, ‘I sure am. I should have gloved the sucker. I used my bare hand.’ She was one of those irrepressible people who always squeeze the most out of life.

My second family was the Liebermans. When we moved to Suffern, New York, on the first day of tenth grade at my new school, the place was in chaos because a girl had been sent home for wearing a skirt that was too short. That girl was my future wife, Marla Lieberman. Marla’s family made an indelible mark on my life, in the best way. Her father, Ephraim, was a physicist and a great humanist, a very intellectual man, and he was the person who took me on my college tours. His grandchildren describe him as a cross between Einstein and Kermit the Frog! Marla’s mother, Lenor, was in contrast to Ephie the dreamer, the level headed practical, organized, crossword addict and nightly Jeopardy playing phenom who opened her home and heart to me from day one.

At school, I had great teachers and great programmes. Sports were very big for me, and music too, alongside student government. I always did very well in school, but I worked my tail off, and Marla rightly describes me then (and now) as a nerd. Even so, when I went to meet the high school guidance counsellor and said I was thinking of applying to Ivy League schools, he was dismissive. One of the things I can credit my two families for is that I have always been motivated to prove that such folks are mistaken. It is one of the earliest lessons I can remember about why to avoid preconceived ideas about people.

On applying for the Rhodes Scholarship

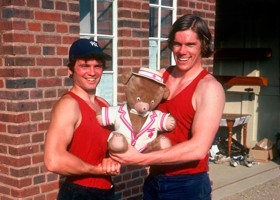

I chose to attend Princeton because I felt I had a lot to acquire in terms of academic background and other experiences and Old Nassau was the best fit for me to grow in mind and in spirit as a person. That’s certainly the way it worked out for me, and Princeton was a huge springboard for the rest of my life. My years there were a blurred whirlwind of total engagement and exhilarating experiences and fun. Academically, I was interested in politics and government from the start, and my commitment to public policy has remained a throughline right across my career.

I always say I’ve been enormously lucky, and part of that was having jobs that got me outside the Princeton bubble. I worked in the dining hall and in the wee hours before breakfast at the university bakery, where one of my colleagues, Pete, the head baker, ended up being one of my Rhodes recommenders. It was the incredible President of Princeton, Bill Bowen, who hired me to tend bar at his events and then got wind of my good grades and activities, and he suggested I should apply for a Rhodes Scholarship. I knew nothing about it – not even how to spell Cecil’s last name– but I filled out the application.

The people competing in the final round of interviews with me were so accomplished that it was a little intimidating, and I certainly didn’t expect to win, not least because I got stuck in traffic in the Holland tunnel on the way to my final interview in Manhattan and missed the original time slot completely. I thought, ‘This is a total trainwreck,’ but they found me another slot, and somehow that unexpected complication was as often seems to happen, was strangely relaxing, and just liberated me from my anxiety. I must have done pretty well under the circumstances.

‘A greater understanding of the world’

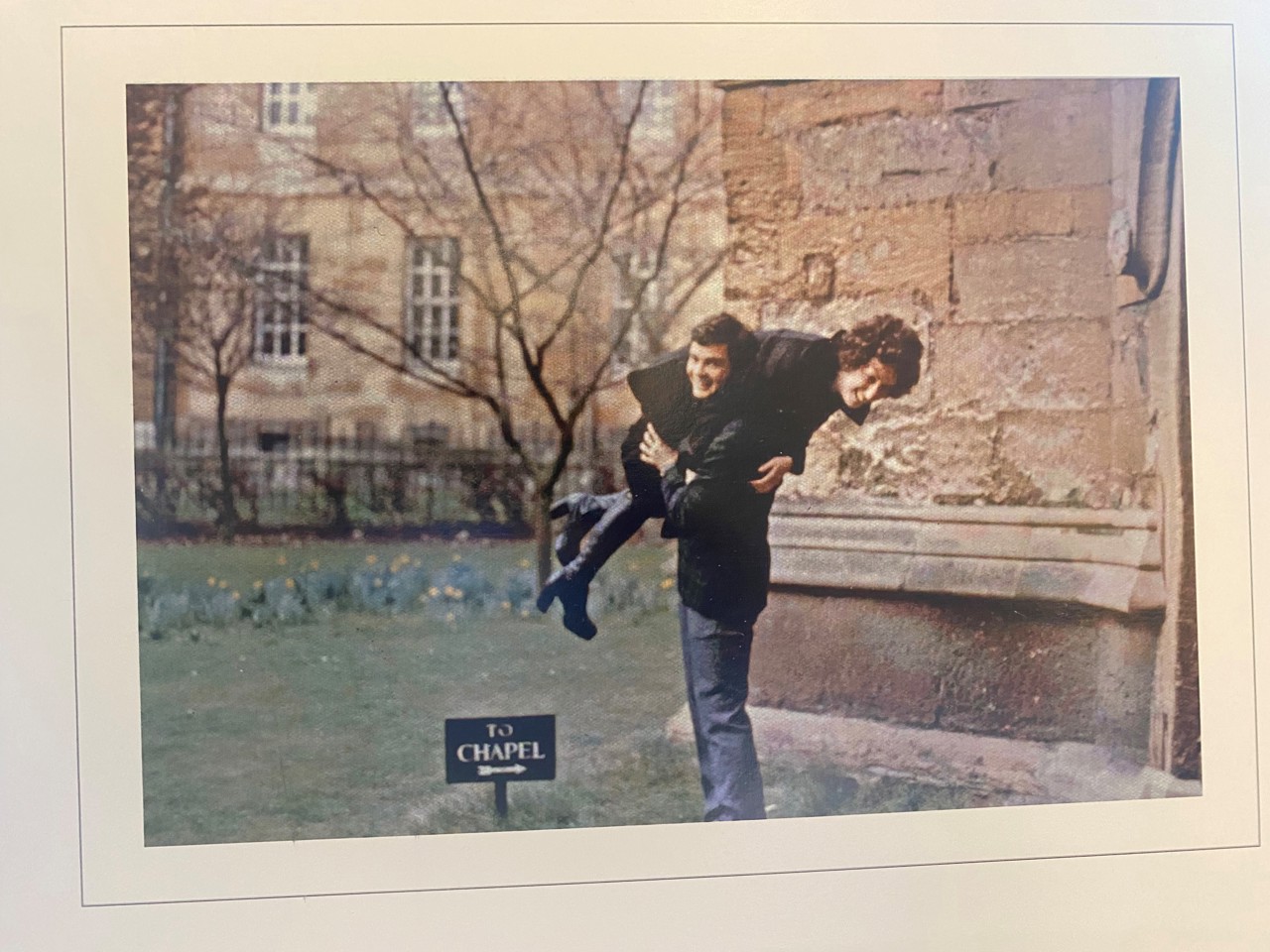

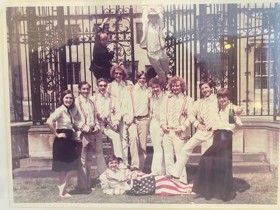

My Rhodes class was supposed to sail over to England together, but at the last moment, the ship’s crew went on strike and we all had to scramble to make our own arrangements. I had travelled so little that it was all new to me. But I think because we literally missed the boat, our class made a special effort to get to know one another, and that bond has stayed with us and grown stronger ever since.

My tutors were amazing. For politics, I had Zbigniew Pełczyński, who as a teenager had survived World War Two with his brother, after hiding in sewers and then in a convent and eventually escaping from Warsaw to live in the forest as a resistance fighter for the rest of the war. He was a remarkable brilliant sweet man. I was also lucky enough to be taught economics by Vijay Joshi, who was a very young tutor then, and with whom I remain close. I had a bit of love-hate relationship with my philosophy tutor, the famous John Lucas. He could be very caring, but for example, he once wrote in one of my reports: ‘Mr Allard not only knows nothing about philosophy, he suspects nothing.’ Pretty rough.

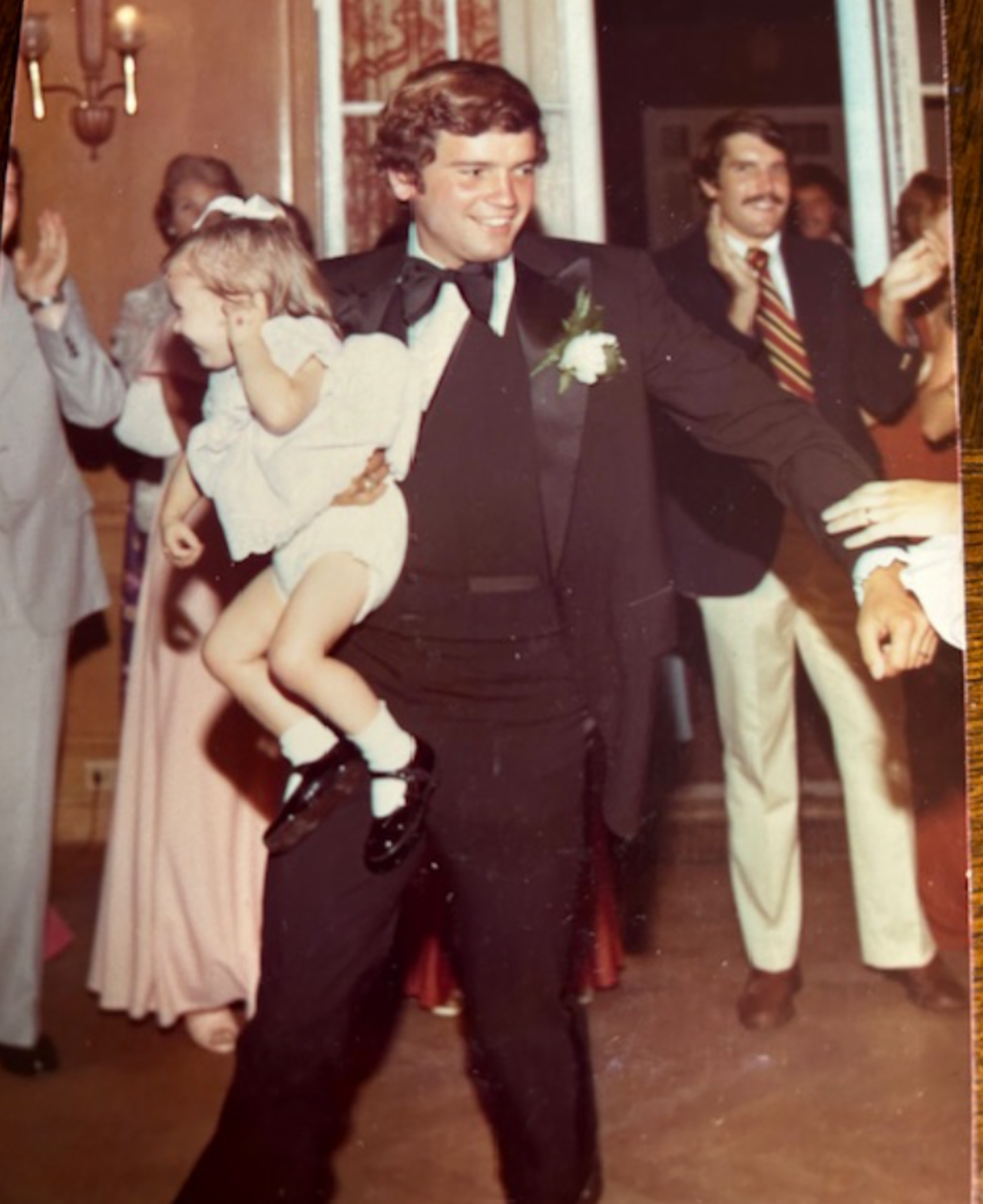

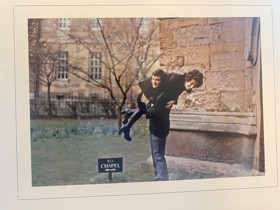

Around the time I arrived in Oxford, the Rhodes Trust changed the rule that Scholars could not be married. For the first time we were permitted to marry after our first year, but only with the Warden’s permission. Marla was also studying in the UK then at Sussex University, and we decided to get married. So off I went to see Sir Edgar Williams who knew Marla well and in many ways, he had been friendly and helpful to her. Even so, the obligatory pre-nuptual conversation with the Warden was pretty weird and uncomfortable. Years later I learned that poor Sir Edgar had been even more uncomfortable than I was: the Trustees had insisted on his approving each marriage, based on determining that the Trust would not be responsible for covering debts in case our wives turned out to be extravagant spenders! But he gave permission, and Marla and I, and every one of my several classmates who sought permission, were married that summer.

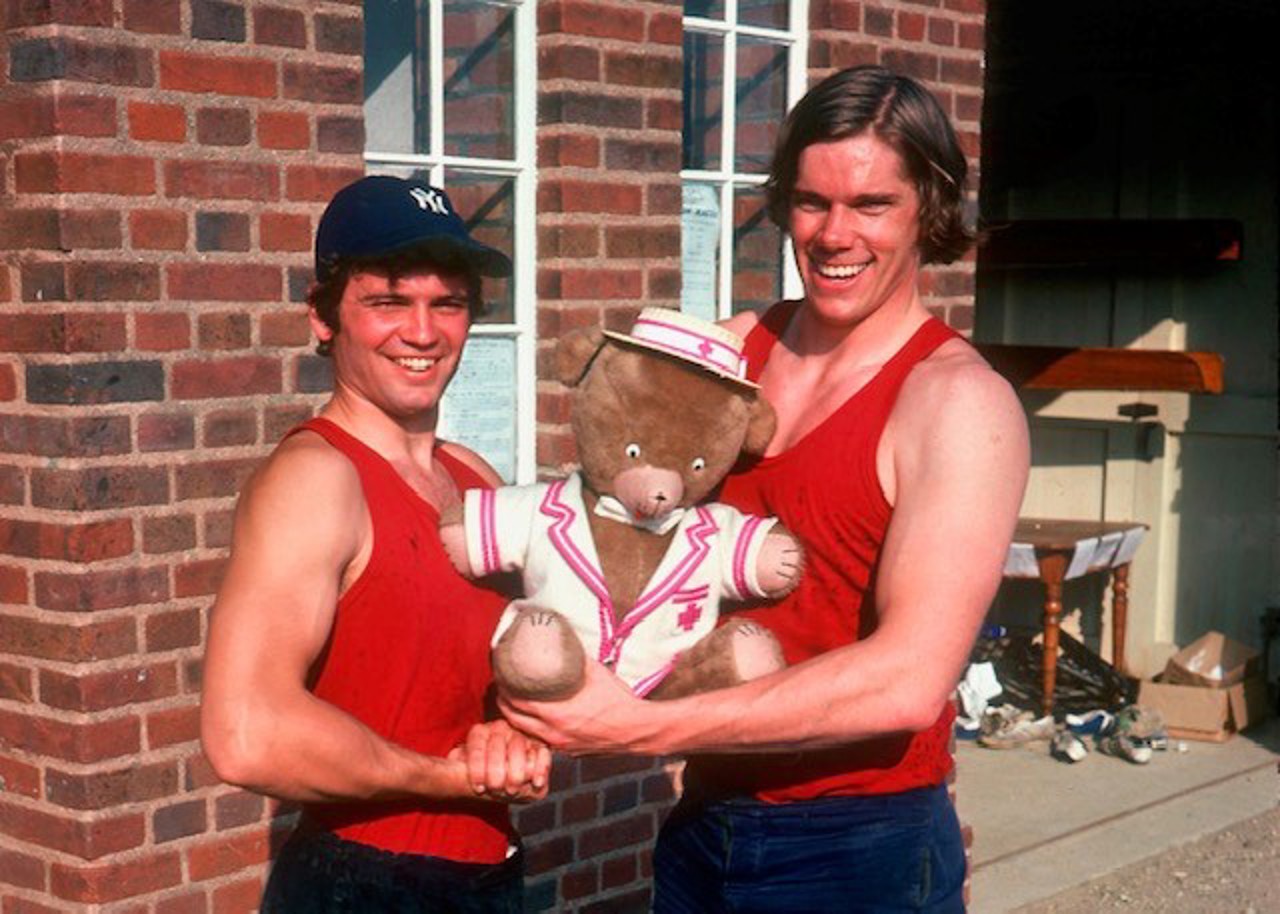

Merton let us live in a beautiful tiny white five hundred year old cottage, right in the centre of town in a hidden courtyard adjacent to the Turf Tavern. It was a wonderful start to married life, and we were also able to travel throughout England, to Scotland, Ireland, France, Greece, Italy, Yugoslavia, Austria, Germany and to Israel. The Rhodes Scholarship gave me so much. The intellectual and academic sharpening and the opening of my understanding of the world and other people’s perspectives was priceless. But the most valuable thing was certainly the people with whom we have remained close throughout our lives.

‘We’re in a new era’

My J.D. was earned Yale Law School, which was terrific. After law school, I had a series of judicial clerkships, first with Chief Judge Robert Peckham in San Francisco, and then with D.C. Circuit Judge Pat Wald in Washington. They were both extraordinary people, and I was especially proud to be part of several important decisions both jurists issued. for example, I was part of the team that worked on Sierra Club v. Costle, which still stands as one of the major environmental and administrative law decisions of our time. After that, I worked in public policy and that led to me, at a very young age, to serving as minority counsel for Senator Ted Kennedy on the U.S. Senate Judiciary Committee, and then becoming the chief of staff for Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan. Eventually, with three small children and after my father-in-law Eph advised me to “get a real job,” I went into private practice focusing on public policy issues especially in health, communications, technology, and higher education. I also stayed very active politically. By 2010, I was leading the number one public policy practice in the world, Patton Boggs, and finding that the most interesting work I was doing was with higher education. So, when a group of friends and mentors suggested I should think about being the head of a college, or dean of a law school or public policy school, I was very open to the idea.

I loved my time at Brooklyn Law School and felt greatly honoured to be there. Then, I was given the chance to do something entrepreneurial in higher education and become the founding dean of Jacksonville University College of Law. We’re in a new era, and there is such a need to help prepare young people to use the most powerful tool ever known, a legally trained mind. What we’re building into the DNA of Jacksonville is a constant, dynamic mechanism for innovation and adapting legal education to meet the challenges we’re facing in the world today.

Somebody wrote a phrase about planting trees whose shade you won’t get to sit under. Marla and I borrow from that idea in our lives and within our work in higher education. This is because both of our families come from extremely modest backgrounds but were able to use the power of education to powerfully transform their lives and their future family members’ lives. And most importantly, make a positive difference by planting trees whose shade others will enjoy.

‘Don’t take yourself too seriously’

Marla and I both understand from our own lives the power of education to transform lives. That’s what drives us, from a very deep and personal source, to extend a hand so that other people can benefit.

My family is the most important thing to me, and although my kids joke that my humility is world-famous, I do reflect on my own shortcomings. My faith and religion give me an important, I believe, universal framework in which to do that. I also think a lot about how much I have benefitted from the support and mentorship I’ve had throughout my life, in all areas.

To today’s Rhodes Scholars, I would say, work hard, but also find time to relax, and don’t take yourself too seriously. And remember, you should try to find a true match for your abilities and interests, because the most worthwhile thing for you to do isn’t necessarily the one that’s most prestigious or the toughest to get.