Born in Chennai in 1968, Mukund Rajan studied at the Indian Institute of Technology (IIT) in Delhi before going to Oxford to read for an MPhil and DPhil in international relations. Returning to India, he entered the Tata Administrative Service, going on to become executive assistant and then chief of staff to the Tata Group Chairman, Ratan Tata and to hold the CEO roles in two Tata companies. Under Ratan Tata’s successor, Rajan was appointed as the first brand custodian for the Tata Group, before leaving in 2018 to set up his own company, ECube, which focuses on helping Indian companies to navigate sustainability and ESG challenges. He is the author of Global Environmental Politics: India and the North-South Politics of Global Environmental Issues and Outlast: How ESG Can Benefit Your Business, as well as two books on the Tatas, including The Brand Custodian: My Years with the Tatas. In 2024, The Rhodes Trust was delighted to announce the endowment, in perpetuity, of a sixth Rhodes Scholarship for India, and the Trust is enormously grateful to Dr Rajan and his wife, Mrs Soumya Rajan, for their generosity and leadership in establishing this Scholarship. This narrative is excerpted from an interview with the Rhodes Trust on 4 December 2024.

Mukund Rajan

India & Worcester 1989

‘It was like a ticket to the future’

My father had joined the Indian Police Service in 1953, soon after Indian independence in 1947, when there was this real sense of commitment to wanting to help India emerge from poverty and all the issues it had had as a colony. He was chosen to work with India’s external intelligence agency, so, he became what you might describe as a spook. He actually served in a series of missions of India overseas, and my first years were spent in Jakarta, in Colombo and then in Brussels, before we came back to India when I was six. It didn’t take me long to adjust, but India in the 1970s was still a very poor country, and you could certainly make out the difference and see the privilege of growing up in a European country.

I never really enjoyed school, and all the regimentation that went with it, but I made friends, and there were subjects that I liked, especially history. I didn’t particularly enjoy the sciences, but those were the subjects you had to do well in if you wanted a chance of a good career in India in those days. Until the early 1990s, India was pretty much a socialist state. There was a scarcity of well-paid jobs, and most smart young people had to choose between being a doctor and being an engineer. I went on from school to the IIT in Delhi to study engineering. Getting in was hugely competitive, but once you did get in, it was like a ticket to the future.

On applying for the Rhodes Scholarship

At that time, there were very few scholarships from India to go to universities in Britain like Oxford. It so happened that a good friend of my older brother had got a Rhodes Scholarship, and I remember going to meet him and coming away quite inspired about the possibility that I could also apply. It was the late 1980s, the cold war was ending and a new world order was getting established, and I wanted to move out of engineering and into the social sciences as a way to explore what was happening.

I think the people on the committee that interviewed me for the Scholarship were a little puzzled about why this engineer wanted to change subjects, but I’d heard a lot about Oxford’s tutorial system and I really wanted to be in an educational environment where you were encouraged to think for yourself and to write essays and defend your arguments in front of your tutor. I guess luck was on my side and they decided to take a punt on me!

‘I was just on this mission to learn’

Oxford really did live up to my expectations, and in full measure. I spent the first few weeks there feeling a bit traumatised, because I got the reading list for the MPhil when I arrived and there were 1,400 books on it, and it turned out my classmates had been sent the list much earlier. I then spoke to somebody who was already studying there, who assured me that you only really needed to focus on certain topics and make sure you had detailed knowledge in those. After that, it was plain sailing, and I really enjoyed my time. I got very interested in how countries were negotiating to reach agreement over taking action about the depletion of the Antarctic ozone layer, a precursor to addressing other global environmental challenges like climate change, and I went on to write both my MPhil dissertation and my DPhil thesis on that area.

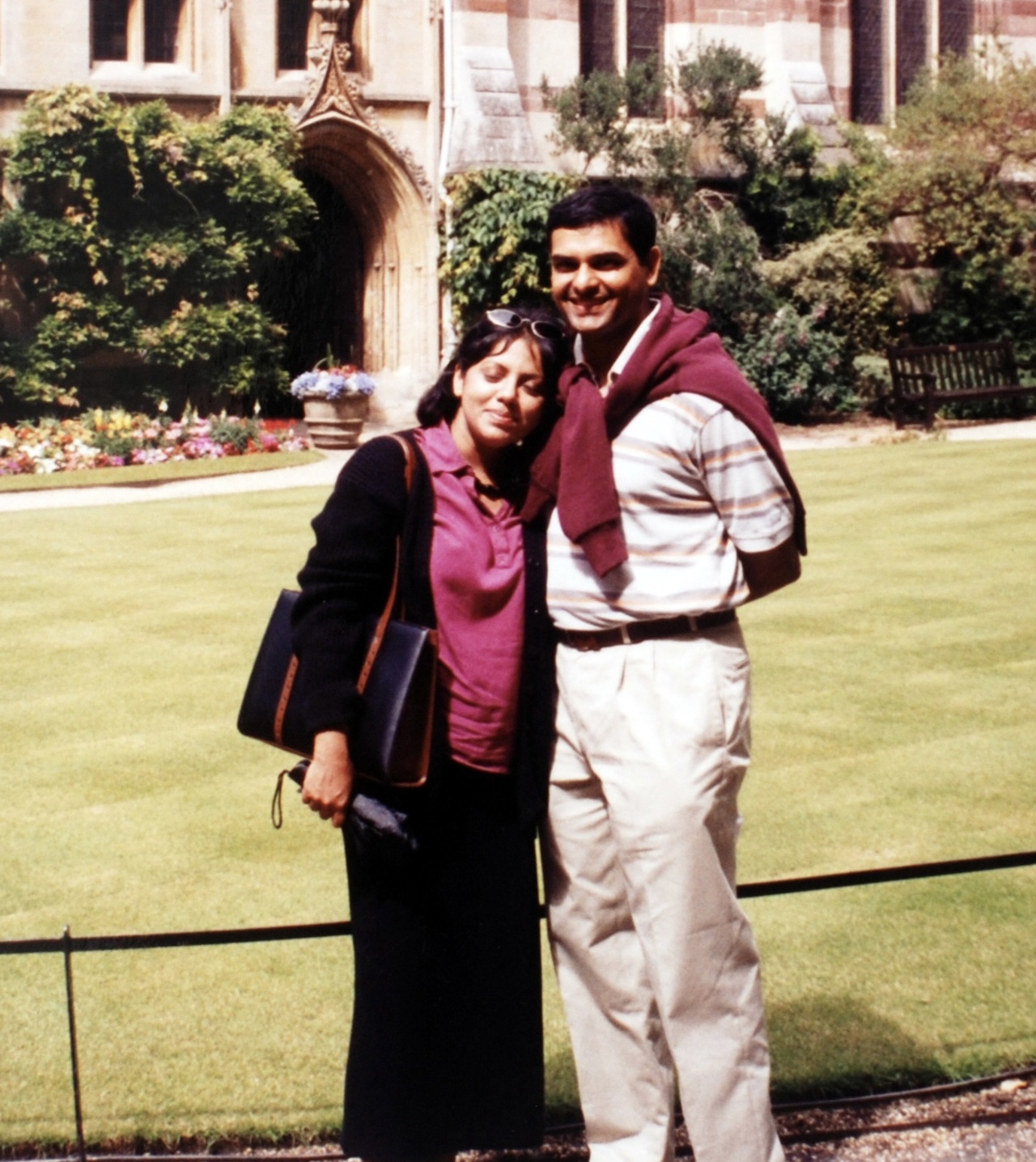

I have to say, I did miss out on some of the social and fun stuff at Oxford, because I didn’t have a BA in political science and that meant I had a lot of reading to do in order to get with the theoretical frameworks. But I have no regrets, because I was just on this mission to learn. And, very importantly, I met my wife at Oxford, and, of course, that was something that became transformational, not least because I came back to India, hot on her heels.

‘The best part is, every day, you go in and you learn something new’

When I got back to India, I knew that the book based on my doctoral dissertation was coming out, for which I had a contract with Oxford University Press. That bought me time do something else. I had thought about going into academia, but was keen to first spend some time understanding the massive changes taking place in India’s corporate sector. In 1991, after a series of economic challenges, the Indian market had begun to open up, and some of the largest corporations in the world were moving in. The Tatas, at that time, as they still are today, were India’s largest corporate house, and they had a programme called the Tata Administrative Service, modelled, in a way, on the Indian Administrative Service. So, I wrote in to see if they might have a role for me. I was interviewed by a committee chaired by Ratan Tata, and they selected me.

Unlike so many managers in the Indian business world, I didn’t have an MBA, and I learnt on the job through a series of assignments with different Tata companies. Mr Tata remembered my interview and in my second year, he invited me to join him as his executive assistant and then as his chief of staff. That was transformational. He was an amazing boss and he gave me a huge amount of autonomy. Pretty soon, I gave up any pretensions of going back into academia. I actually stayed with the Tata Group for 23 years, moving into two CEO roles and then went on to become the first brand custodian under Mr Tata’s successor. In the first of my CEO roles, I moved from a small office to running a telecommunications company with 3000 people, and in the next, it was about setting up a new private equity franchise. Each time, it was something completely new, and the key was figuring out what was required of me and what I could do to add value. I think as long as you’re prepared to acknowledge your own ignorance, your own vulnerabilities, and reach out for help in the right way, you can always find people who are willing to support you. In all the roles I’ve done, I’ve found the best part is, every day, you learn something new. There’s always going to be room to learn more, to improve as a person, and you have to be open to working with other people, figuring out how all of you can together deliver the best.

There were several factors behind my decision to leave the Tata Group, but a major inspiration was watching my wife, Soumya, who had worked in banking, become a very successful entrepreneur. That made me wonder whether I could do something different too. I’d also started seeing that the whole sustainability and climate change agenda was hugely impacting corporate India. So, in 2018, I set up ECube. At that time, a lot of businesses had no idea what ESG stood for. I think we’ve played our role in helping to educate the market, and we have multiple ongoing initiatives, including capacity building and in the world of media. The latest one is a private equity fund that we’re planning to launch to help companies that need capital for the climate transition. It’s great fun, and I especially like the way that my work now has come full circle and connected up again with my research on environmental issues when I was at Oxford.

‘We are thrilled that we are making this possible’

Soumya and I met at Oxford, and being there was lifechanging, for both of us. I think we both thought that if we could make that experience available to others, that would be terrific. I know that I’ve benefited enormously from both the Rhodes experience and from the networks that the Scholarship offers. So, we felt we owed it to ourselves to pay back and to pay forward possibilities, and that’s why we decided to take the lead in supporting the new sixth Scholarship for India. We’ve chosen to name it after both Soumya’s great-grandfather, Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan, who was the Spalding Professor of Eastern Religion at Oxford in the 1930s and a fellow of All Souls College, and after my father, Raghavachari Govindarajan, who was such an inspiration to me. We are thrilled that we are making this possible for young Indians.