Born in 1937 in Izatnagar in the United Provinces in British India, Moni Malhoutra studied at St. Stephen’s College, University of Delhi before going to Oxford to read for a second undergraduate degree in history. On returning to India, he joined the Indian Administrative Service and worked with Prime Minister Indira Gandhi in her secretariat. Malhoutra went on to be Assistant Secretary General of the Commonwealth Secretariat and was a member of the Board of International IDEA (International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance) and Secretary-General of the Rajiv Gandhi Foundation. He has edited a number of works, including An Indian Social Democracy and India: The Next Decade. This narrative is excerpted from interviews with the Rhodes Trust on 26th September and 29th October 2024.

Moni Malhoutra

India & Balliol 1958

‘Life was slower, but it was very enjoyable’

The first ten years of my life were the last ten years of British rule in India. India was a much poorer country at that time, much less educated, much less urbanised, much less crowded. The cities were safe, there was little traffic and life was slower, but it was very enjoyable.

My father was in the Indian Medical Service. It was a branch of the British Indian Army, so wherever the Army went to fight, the Indian Medical Service went with them. In World War Two, my father had been posted to Singapore. When I was about three and a half years old, Singapore surrendered suddenly to the Japanese and my father was taken a prisoner of war. We did not know at that time whether he would ever return, whether he was alive or dead.

We went to live with my mother’s family in Amritsar. Her father was a cloth merchant, and she remembered Gandhi coming to Amritsar when she was little. Gandhi had called for a boycott of all British goods. When he saw her wearing her pretty English cotton frock, he said she should burn it, but she refused. She was always a practical and resourceful woman. She was able to meet the challenges which came her way, especially when my father became a prisoner of war.

Thankfully, my father did come back. At that point, we were put into boarding school. During that time, we became aware that independence was about to be declared but it was only later that I came to understand what partition really meant. I do have a very vivid memory of learning that Mahatma Gandhi had been shot. My family went by train to the Sangam in Allahabad, where Gandhi’s ashes were to be submerged. I still remember the extraordinary, pin-drop silence on the streets as the procession passed us.

On applying for the Rhodes Scholarship

I enrolled in the University of Delhi in 1953. I was not yet even 16, and we were all very young. I was in St. Stephen’s, which was supposed to be the best college, and it was a very fun and engaging experience. The history we were taught was very much Indian history seen through a colonial lens, and I have to say we imbibed it uncritically at that time. I also decided to study French and Russian. I read Tolstoy and Dostoevsky for the first time and was deeply moved by Victor Hugo’s books, Les Misérables in particular. I used to debate, and I was frequently called by All India Radio to take part in radio plays, because I had a good voice and good diction. I loved acting, especially Shakespeare. My other passion was tennis. I used to dream that one day, I would play at Wimbledon: a gross overestimation of my talent!

From a very young age, it had been dinned into our heads that one day, if there was any opportunity, we should try and get to either Oxford or Cambridge. There was no way my parents could afford to send me there, so, when the Rhodes Scholarship came up, it was like applying for a golden passport. Also, Oxford was very strong in history and some of the people whose books I read and enjoyed, particularly A.J.P. Taylor, Isaiah Berlin and Hugh Trevor-Roper, were all based there.

‘A voyage of discovery’

I went to Oxford by boat. The trip took about two weeks. I sailed out of Bombay, got off at Marseille and went to Paris, and then made my way to London and Oxford.

Being at Oxford was a fantastic, rich experience, like a voyage of discovery. So many things coming together, and so much fun: study, travel, conversations, tutorials. It was one of the most stimulating and rewarding periods of my life. I’m very glad I went to Balliol. It was very cosmopolitan, with people from all over the world. It had students from all sections of British society too, not just the grand public schools, and some of the friendships I made have been lifelong.

The history tutors were remarkable. I was taught by Christopher Hill, a wonderfully warm individual and the greatest authority on seventeenth-century English history and by Dick Southern, the medievalist. He was saintly and put you at your ease, but you were aware that you were in the presence of someone who had greater knowledge of his subject than almost anyone else. I went to concerts and to lectures, to the Ashmolean Museum and the Playhouse, and to plays and opera in London. I did a lot of travelling, both in the UK and in Europe. It was the most enriching experience.

‘Working with Indira Gandhi’

I’d done the exam for the Indian Administrative Service when I was in Oxford, and I went straight from Oxford to be trained at the National Academy of Administration in Mussoorie. I was then posted in various districts until I arrived as a district magistrate in the Himalayan district of Uttarkashi, bordering Tibet. That was where I first met Indira Gandhi, who came on official tour. A few weeks later, she chose me to work in the Prime Minister’s office in New Delhi. I was only 29 and it was a heady moment. I was there for seven eventful years. I was given particular responsibility for the environment and for foreign policy. Mrs Gandhi was a passionate environmentalist and lover of wildlife. One of the key projects I worked on was for the conservation of the tiger, whose numbers had dwindled alarmingly as a result of hunting, population growth and development. We launched ‘Project Tiger’, enacted a pan-India Wildlife Protection Act in 1972 to conserve the rest of India’s wildlife and created a series of national parks all over India where no shooting or forestry would be allowed. We literally saved the tiger from extinction. In foreign policy, the big event was the Pakistan army’s bloody crackdown in East Pakistan and its rejection of the election result. Ten million refugees fled to India, causing mounting tension between India and Pakistan. The world worried that there would be war. All diplomatic efforts to resolve the crisis failed. Eventually, in the face of US threats, Indian troops and Bangladesh liberation fighters joined together to defeat the Pakistan army and secure its unconditional surrender. Bangladesh was born. That was a great moment. The refugees were able to return home.

‘The Commonwealth was determined to fight racial discrimination’

Joining the Commonwealth Secretariat in London was a bit of an anti-climax at first, but that changed very quickly. If the British Empire embodied the notion of racial superiority, the Commonwealth was founded on the principle of racial equality. The Commonwealth was becoming quite a lively actor on the international stage, and I found myself deeply involved in Southern Rhodesia, and then in South Africa. In both cases, the role which the Commonwealth played was important and productive. In Rhodesia, five million black Africans were being denied majority rule by the small white minority. In the aftermath of a prolonged civil war between whites and blacks, the Commonwealth sent a multi-national Commonwealth Observer Group to monitor the pre-independence election in 1980. It was a fraught exercise. We weren’t popular, either with the white government of Southern Rhodesia or with the British government, both of whom wanted a particular party to win, but our vigilance and interventions at critical moments helped ensure a free and fair election and international recognition of the outcome, with Rhodesia becoming Zimbabwe.

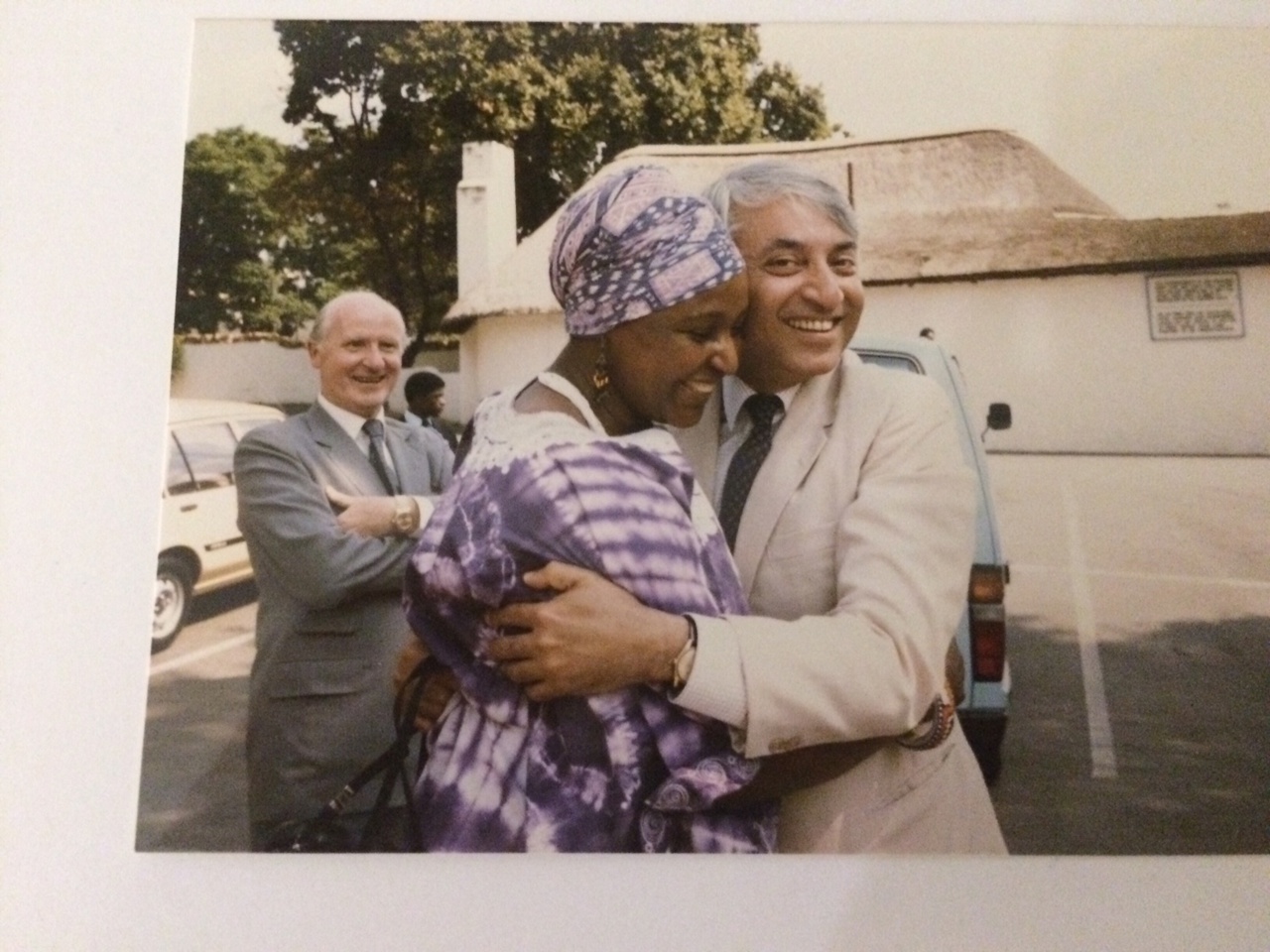

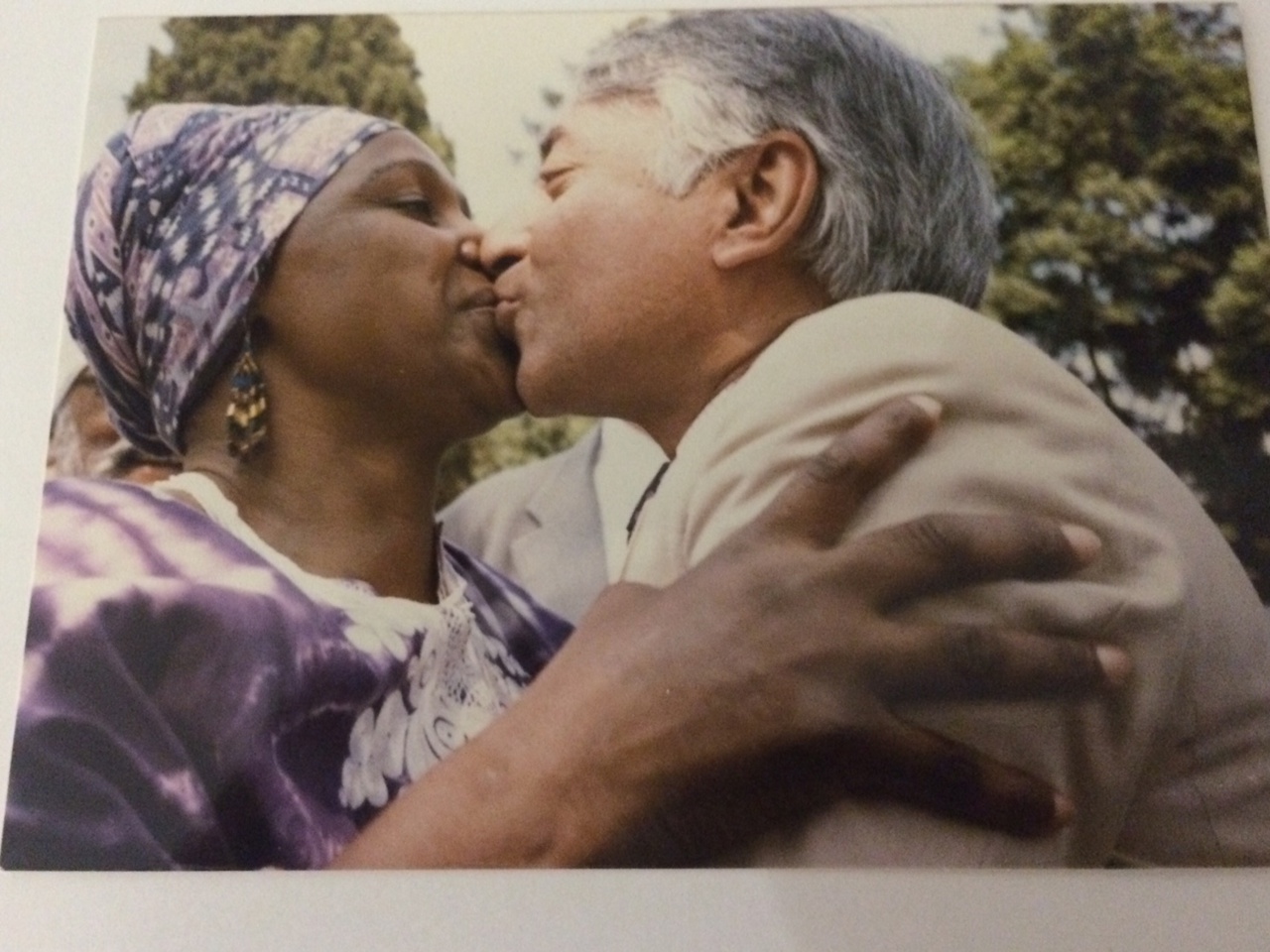

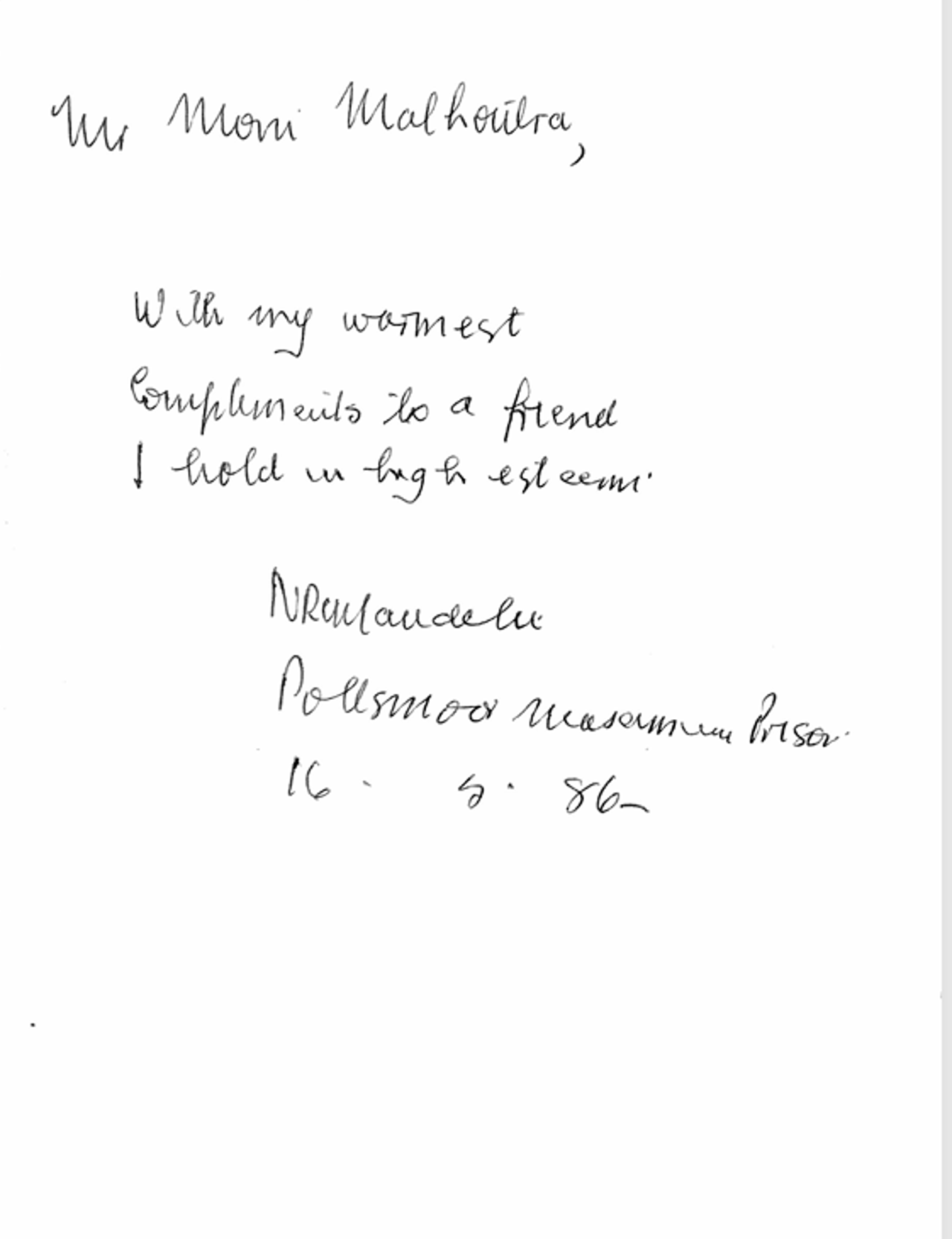

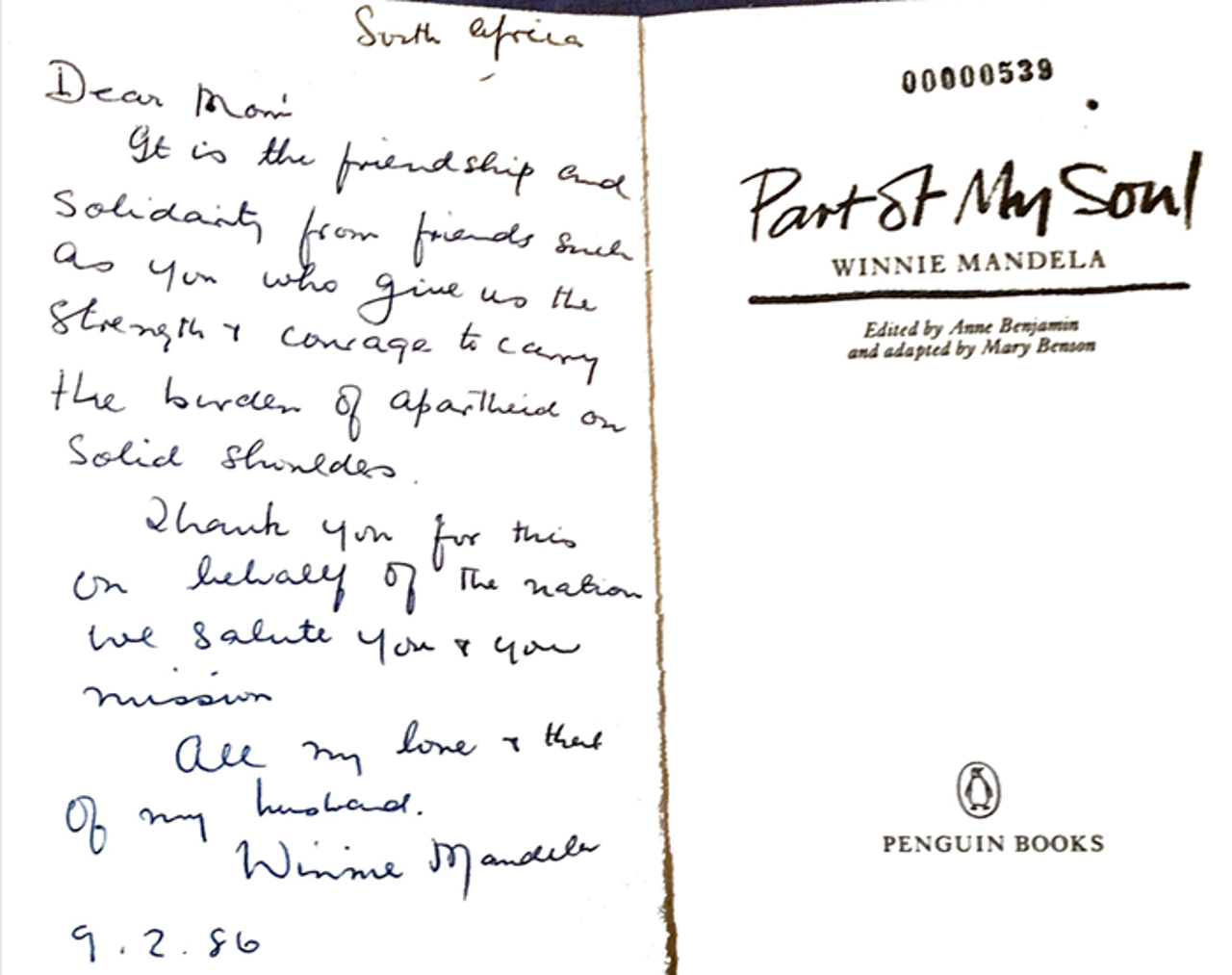

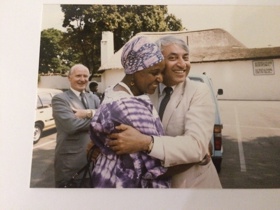

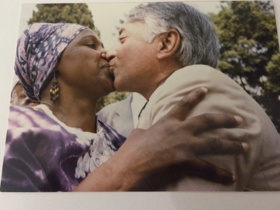

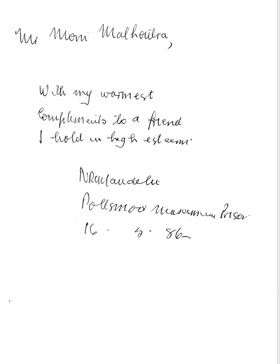

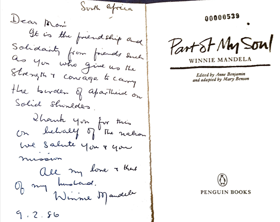

In 1986, the Commonwealth sent an Eminent Persons’ Group to South Africa to try to persuade the apartheid government to change course and move to a non-racial South Africa. The Commonwealth was extremely determined, as it had been in Rhodesia, to fight racial discrimination and end the spiralling violence in the country. We held detailed discussions with President Botha and his ministers and people from all sections of society. We also met Nelson Mandela in Pollsmoor Prison. He was a very commanding figure. You could see the authority that he exuded. Even his jailers were respectful towards him. He laid out his vision for a non-racial South Africa and told us that his meeting with the group was the most important in his 24 years in prison and welcomed our efforts to break the deadlock and start genuine negotiations. In the end, at that time, our work did not bring the resolution we wanted as our negotiating concept - steps to be taken before negotiations could begin - was rejected by the South African government. In our failure lay success. When we got back to London we published our report. The rejection of the group’s proposals triggered a wave of stringent sanctions against South Africa by the US, Europe and the Commonwealth (except Britain), which three years later forced the government to release Nelson Mandela, ironically on the very conditions set out in our negotiating concept. When Mandela was released, he and Winnie Mandela came to London to thank those who had helped them. Their first port of call was the home of the Commonwealth Secretary General.

‘Face the challenges of life with courage and humility’

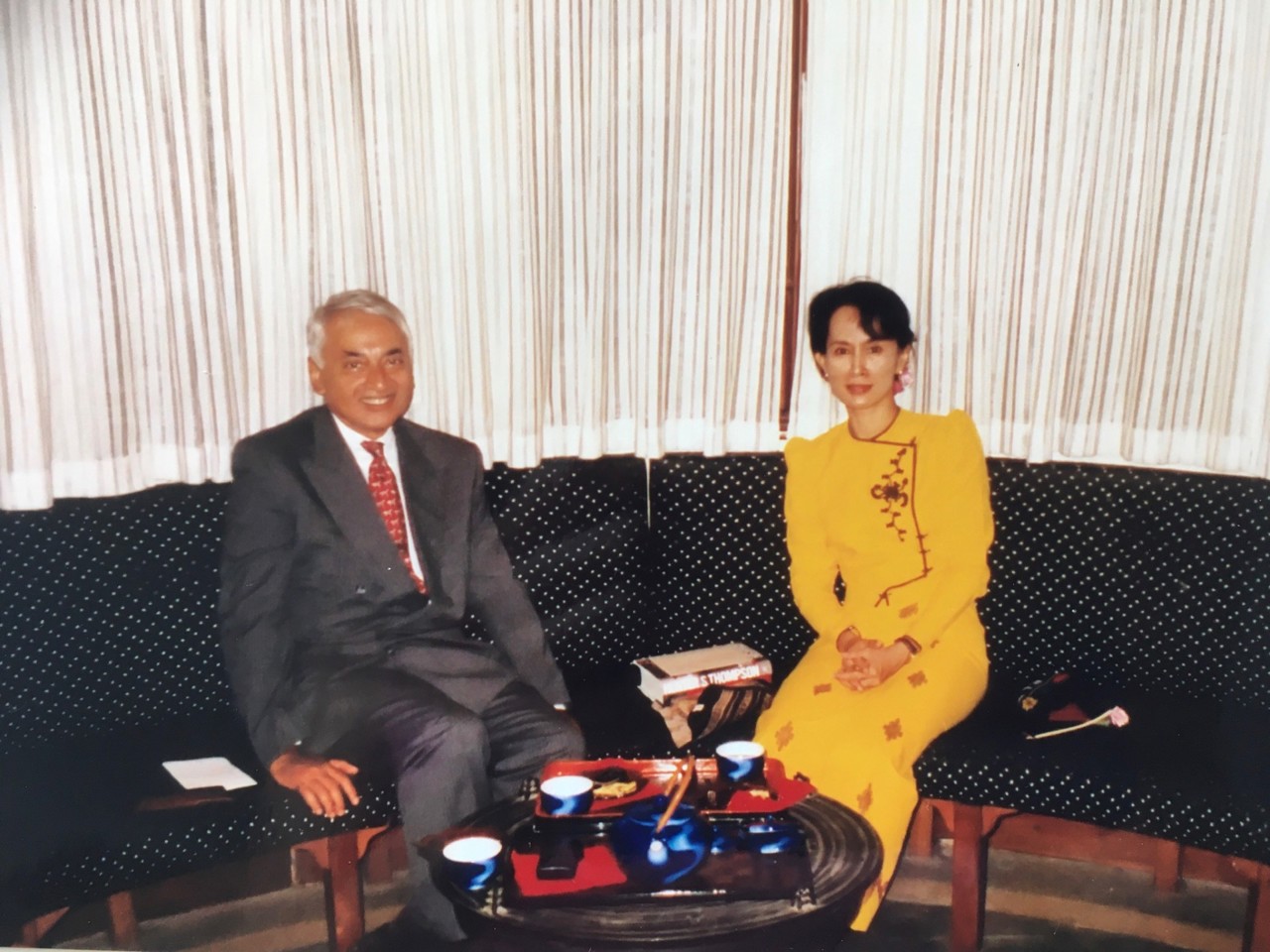

For the last 20 years, I’ve been involved with a number of organisations, including International IDEA (the inter-governmental think tank on democracy) which sent me to Myanmar in 1998 to meet Aung San Suu Kyi, then under house arrest, to discuss ways of helping the democracy movement. A lot of my time now is dedicated to working with CanSupport, a cancer charity which offers palliative home care to the very poor in India who cannot afford the costs of healthcare or are beyond treatment. When I talk to our workers and say, ‘This is really difficult work you do, facing these terrible emotional situations,’ they say, ‘No, we are doing God’s own work.’ It’s enormously inspiring. To today’s Rhodes Scholars, I would say face the challenges of life with courage and humility and believe in yourself. I think the best thing we can do, working on our own or together, is to try, in whatever way we can, to make the world a more just place or a less unjust place.