Born in New Zealand, Merata Kawharu studied at the University of Auckland before going to Oxford to read for a DPhil in anthropology. Returning to New Zealand, she took up an academic post at the University of Auckland and went on to be a Research Professor at the Centere for Sustainability in the University of Otago. She is currently Deputy Vice-Chancellor Māori at Lincoln University. Alongside her academic work, Kawharu has held roles with the United Nations, UNESCO, the NZ Historic Places Trust Board and Māori Heritage Council and the New Zealand Geographic Board. In 2012, she was appointed a Member of the New Zealand Order of Merit for services to Māori education and in March 2025, she was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society Te Apārangi. This narrative is excerpted from an interview with the Rhodes Trust on 20 March 2025.

Merata Kawharu

New Zealand & Exeter 1994

‘I was comfortable in both worlds’

I was brought up in Palmerston North in New Zealand. I was brought up in the western world, but I lived also very much in the Māori world. So, tribally, I affiliate to iwi or tribal groups in the northern part of New Zealand, and most holidays, we would go north to visit them. My parents were both strongly affiliated to and involved in these tribal regions in leadership roles, but they were also strongly linked to the city and communities in the south where we lived, so I was comfortable in both worlds.

We stayed in Palmerston until I was about 13 and then moved to Auckland. Moving there was an opportunity for my father, who was an academic, to go home to his tribal people and be closer also to my mother’s tribal people. In Palmerston North, he had established an inaugural department of Anthropology and also Māori studies, and when we moved, he took up a position at the University of Auckland.

Because of what he did, I had grown up seeing the first people in iwi families to go through and do postgraduate studies and then become academics in their own right, and in the case of Māori women, do doctoral studies while having families at the same time. I didn’t think anything of it, but it was something that was ahead of the time. My dad always looked out for the potential in people and then did what he could to nurture and support them, so they could become recognised leaders in their own right, both in terms of an academic setting as well as their community setting. So, I was surrounded by these kinds of individuals all the time and I guess, with that kind of background, I just thought, ‘Oh, well, that’s what I will do later.'

On applying for the Rhodes Scholarship

I didn’t actually do that well in my final year of high school, and although I enrolled in a Bachelor of Arts in anthropology, I realised I wasn’t quite ready and I un-enrolled and decided to take my first year out. I went and worked for a government department and then travelled internationally. I just needed to find my feet a little bit, and I got to know my peers in Auckland. I became very close with one tribal relation and we used to think about the big issues of the day whether it was tribal development, economic development, local politics or a myriad of other questions facing young people. We would call tribal meetings, bringing the leadership of our tribe together with the young people to discuss the challenges ahead, priorities, goals and our grounding values. So, I was trying to contribute something meaningful in some kind of leadership capacity at that point.

It was towards the end of my undergraduate studies at the University of Auckland that I began to think about postgraduate work overseas. When I looked for the best place for my discipline – social science, anthropology – Oxford was historically one of the best, and it was also where my father had studied. My broad idea was to deepen my skills and insights overseas and then bring those experiences home and serve my communities of interest. I saw that the Rhodes would fund students to go there, so I gave it a shot. In terms of the actual national interview in Wellington I had the usual nerves, but I remember it also feeling like a conversation. I think the ease that I had was partly because I’d been lucky enough to have good mentoring from John Hood (New Zealand & Worcester 1976) and from my family, and also because I tried to go in with no expectations of the outcome and to take it as it is, come what may. When the announcement was made and my name was read out, I remember feeling quite overwhelmed and thinking ‘now what?’ Fortunately I had several months to figure that out!

‘I was studying from the inside out rather than from the outside in’

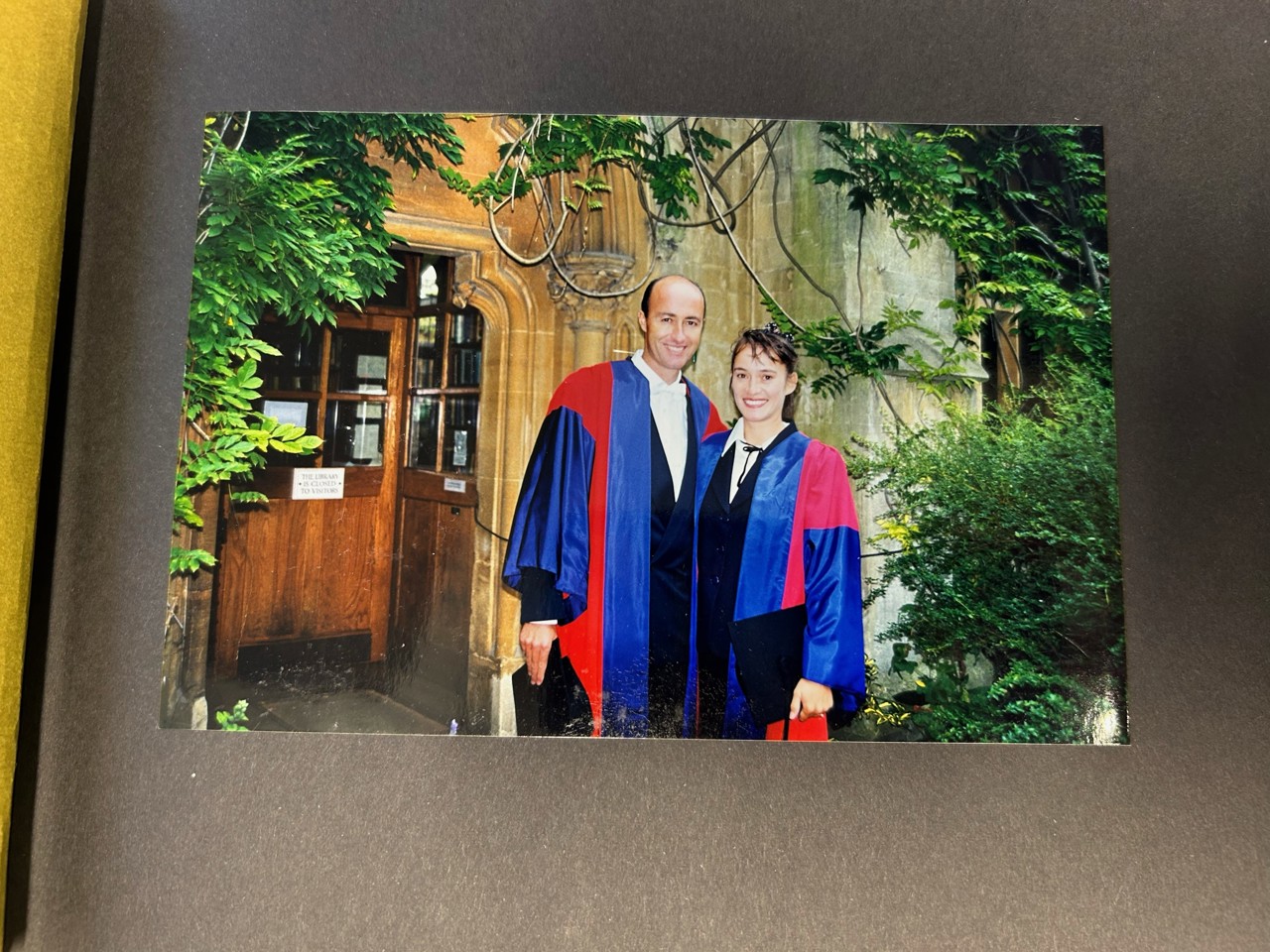

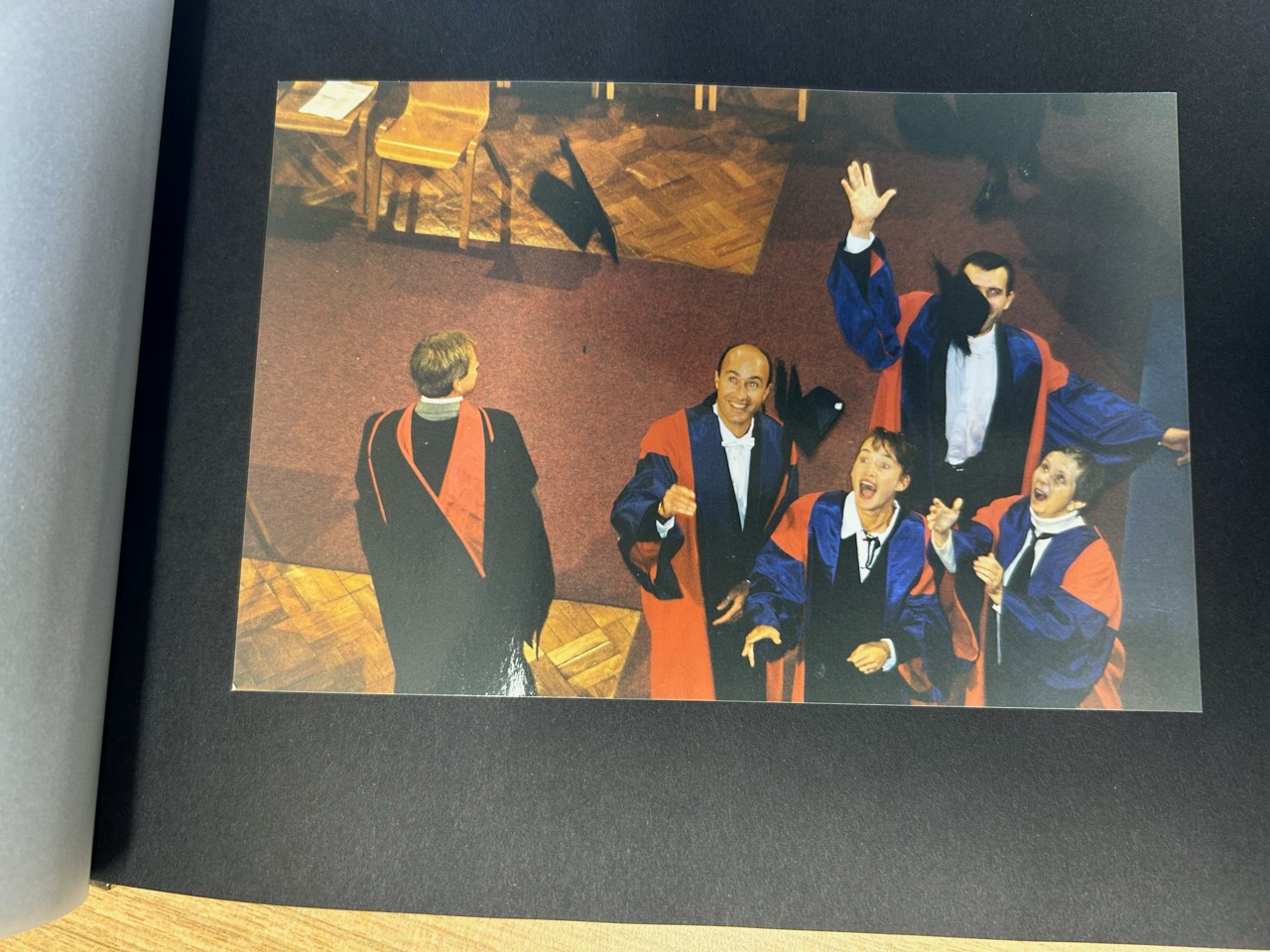

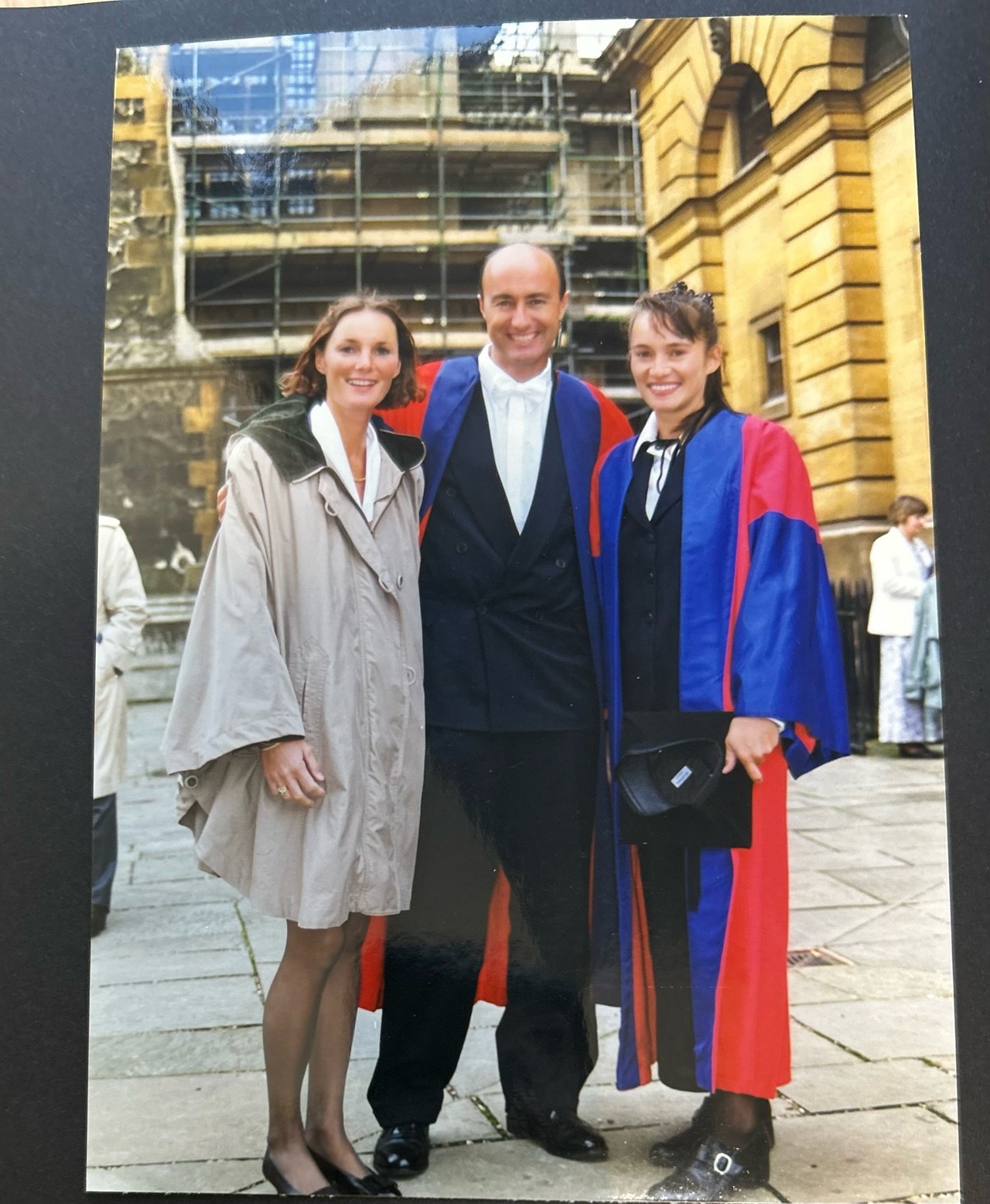

I’d actually lived in Oxford for a time as a child, because my father had had a sabbatical there, so I knew the city a little bit. When I went back as a Rhodes Scholar, it was a unique time to be at Oxford as a New Zealander. There were four Māori there at one time, which I think was unprecedented. I already had a broad sense of what I wanted to do in my DPhil, in terms of training around economic development, cultural development and entrepreneurship so that I could make some kind of contribution. I ended up focusing on an environmental concept of kaitiakitanga or stewardship/trusteeship, and the legislative frameworks in New Zealand for environmental law, looking at western law and customary law and how the two work or don’t work together.

In terms of progressing my studies, I had different layers of people advising me because Oxford didn’t have experts specifically in the field I was working on, but my supervisors Chris Gosden and Howard Morphy were constant guides and kept me focused on the big picture ahead. Fortunately I also had my father who helped me simplify my ideas about what should go into the thesis. And I had experts from within the community and other New Zealand-based academics who I leaned on from time to time. I was starting at a time where there were significant advances going on in anthropology in terms of methodological approaches. As an Indigenous scholar, I was studying from the inside out rather than from the outside in, and I’d been immersed in these communities for my whole life. That made the work I was doing more of a natural dialogue and process and where our ways of conducting research were nuanced towards co-productive outcomes. The slightly difficult part was with the Rhodes Trust itself, because normally they encourage you to be a Scholar in Oxford, but I had to get special time out to be able to go back and do my fieldwork in New Zealand.

In addition to the community side of things, I was also doing a lot of archival, literature-based research, including legal submissions for what became the Resource Management Act. This statute was the first to incorporate kaitiakitanga into law. The law itself was the principal environmental and planning legislation, and one of the largest and most complex statutes in the country so how kaitiakitanga was dealt with was and has been a critical issue. I was also interested in its historical context, the narratives around how communities had managed the environment and what the challenges were to that when colonisation occurred. So, your community had lived in an area, had managed vast estates of natural resources, but then you had a western system where settlers needed land and resources. That had major implications for local people and significant land was lost. And, of course, there were vast changes to the landscape with deforestation and agricultural changes, and that resulted in huge economic and political shifts. Communities could no longer survive, and many moved to cities.

A legacy of this history is seen in depopulated rural communities and limited capacity to deal with environmental, economic or cultural issues. It’s often a small leadership group who hold multiple roles. And with climate change happening now, existing problems are exacerbated. What are the solutions? It’s about taking the best of western science, the best of our customary knowledge and the best of AI and other modern technology to co-design and co-develop solutions. We have to work together with local government, the private sector and farming communities who all want to see healthy lands, healthy waterways and secure forest futures. Bringing all of that together in terms of good kaitiakitanga practices, environmental practices, is where my work continues, based on what I did all those years ago in Oxford.

‘I’m motivated by identifying the gaps and opportunities’

I had thought about working in an international context after Oxford, perhaps with the UN or with McKinsey, BCG or other consultancy. But by the time I finished my DPhil, my mother’s health wasn’t great so I returned to New Zealand and took up a couple of private consultancy contracts before John Hood asked me whether I would like to apply for a position at the University of Auckland, where he was then Vice-Chancellor. I did, and was successful, and I’ve continued to work in universities alongside my consultancy projects. Currently, I’m Deputy Vice-Chancellor at Lincoln University, where my focus is on promoting student and research successes and putting what we do to the service of our communities as well. At the moment, for example, we are looking to create a master’s degree in AI and land use which I believe will be the first of its kind anywhere, and we’re asking, as our communities undergo transformative economic change, how do we move from being under-productive to generating wealth and wellbeing while also ensuring environmental health?

My trajectory of working in and for communities has continued over the years. Climate is obviously an issue facing all of us, and so, I’m concerned with questions around the pressing issues facing our communities and what we need in order to be resilient. I’ve led multidisciplinary projects, bringing a diverse range of experts together to consider these issues. I’ve also been on the board of the Māori Heritage Council where I was the youngest on the board at the time. An aim was to influence the legislative agenda, getting new concepts into law to recognise special places and put a national heritage framework in place.

I’m motivated by identifying the gaps and opportunities, by working out how we need to pivot and what that requires. That means you have to think creatively and I’m especially interested in models of entrepreneurial, vision-making. But ultimately too, its about working collectively with like-minded people. Knowing that you’re leaving a legacy for future generations drives you. And knowing you’re doing it with people that share those aspirations sustains you.