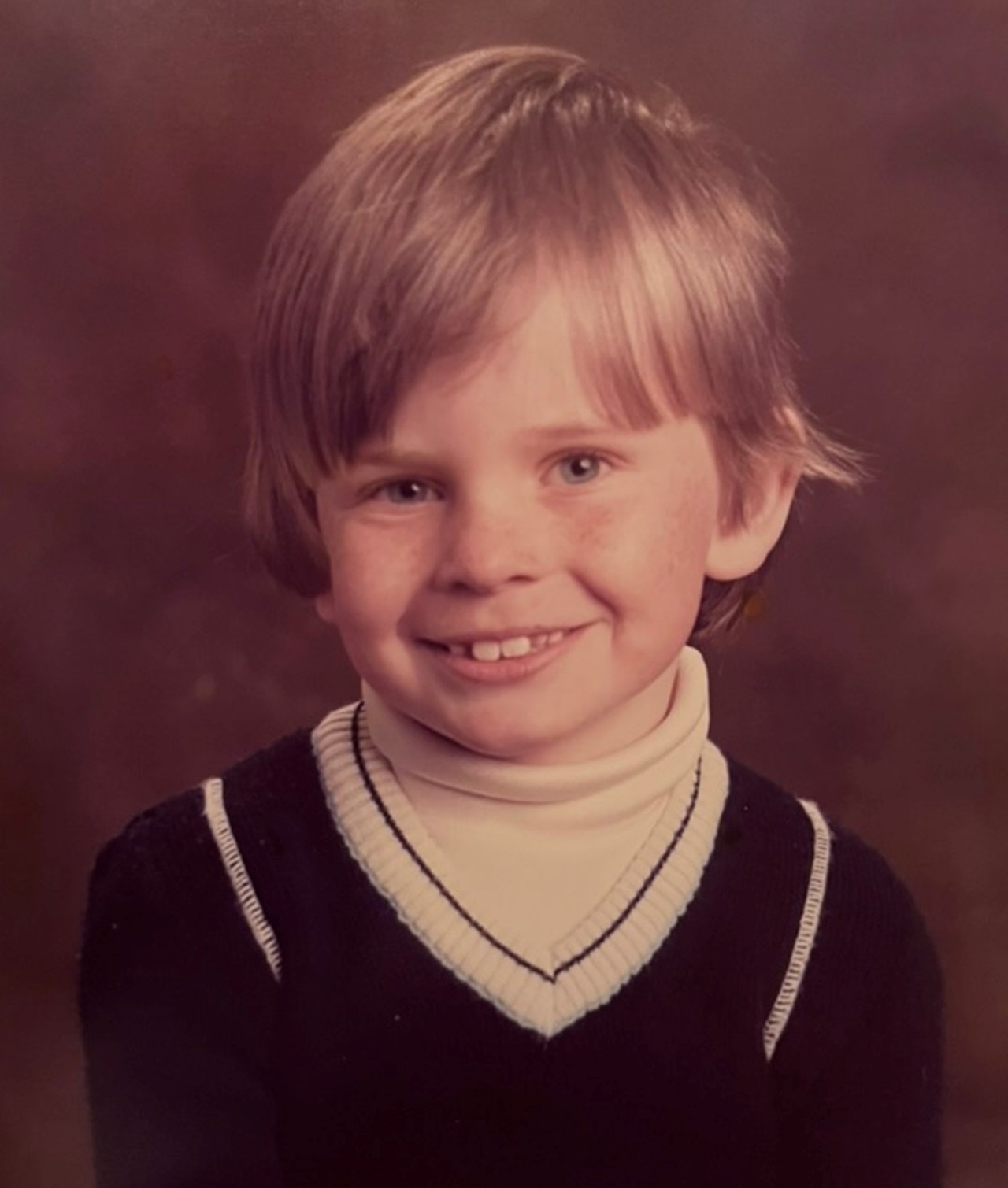

Born in Dundalk, Ireland in 1971, Mark O’Neill studied at University College Dublin and then went to Oxford to complete a DPhil in cardiac physiology as one of the inaugural European Rhodes Scholars. He returned to Dublin to complete his medical studies and then undertook specialty training at St Mary’s Hospital, London and in Bordeaux. O’Neill is now a consultant cardiologist and Professor of Cardiac Electrophysiology at Guy’s and St Thomas’s NHS Foundation Trust in London, specialising in the diagnosis and treatment of complex cardiac arrhythmias. He is a Fellow of the Royal College of Physicians and of the Heart Rhythm Society. In 2025, O’Neill joined the second cohort of Oxford Next Horizons, a six-month experience for those in mid to late career, offering the chance to think, explore and reinvent. This narrative is excerpted from an interview with the Rhodes Trust on 26 February 2025.

Mark O’Neill

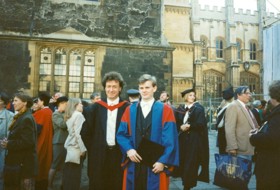

Ireland & University 1992

‘A real community and culture of moral support’

I was born in Dundalk which is in the northeast of Ireland, close to the border with Northern Ireland, but my family moved to the west of Ireland and then to Limerick, which is where I lived until I left home after school. Limerick is the third largest city in Ireland but it’s very small. Our garden backed on to fields, so my brothers and I grew up with a lot of outdoor space. We had the sort of existence where, if you weren’t at school, you got up in the morning and left the house and spent the day outside with your friends, and you only came back to be fed at lunchtime and then again for dinner. There were a lot of kids in my street and we all played together and had a lot of fun. I really enjoyed playing football too, and although I don’t play anymore, I keep a very close eye on the Premier League and I always read the sports pages first at the weekend in the newspaper.

I went to an English-language primary school and I enjoyed it very much. My secondary school, the Crescent College Comprehensive, was on the opposite side of the city. It was a Jesuit secondary school and the principles of Jesuit education were not confined to intellectual development alone but also focused on moral and spiritual growth and the idea that your life should be seen as not just for you but in the service of others. That created a real community and culture of moral support, and I was very attracted to that. Because I was only eleven or twelve at the time, I didn’t realise quite what was happening, but those principles had a really formative effect on how I grew up after that. We were also strongly encouraged to participate in extra-curricular activities and I carried on playing a lot of football and also played rugby and table tennis and did athletics. I did quite a lot of debating, both in English and in Irish, and I took part in the school drama productions pretty much every year until I left.

On applying for the Rhodes Scholarship

I was very ambitious academically leaving school and I put myself under a lot of pressure at university. The first three years of medical school are really tough and you’re being constantly examined on a gargantuan amount of knowledge that you just have to assimilate. So, hard work defined that period for me. And it also turned out that I couldn’t escape the Jesuits! I lived in a Jesuit hall of residence in Dublin for three years. I did continue to play football during my first year, although I didn’t really enjoy it because I was so focused on working. I did get involved in the debating society and I still take part in debates in my professional sphere, because it’s good fun. It doesn’t matter what you’re arguing about. It’s all about the art of the argument rather than the content, and I enjoy that.

I graduated top of my class after three years, which I was proud of, and then I had what was very much a sliding doors moment. I remember that it was a Friday evening in early winter and I had a choice between going to a concert or going to a physiology lecture. I chose the lecture, and when the lecturer, David Paterson, started talking about how someone from Dublin had worked with him in Oxford doing an MSc, I thought that was something I would like to do. I went to my professor and he said ‘Let’s explore it,’ and he got in touch with David and I was accepted to Oxford for the MSc. The Rhodes came about because this was when the Rhodes Trust was piloting European Scholarships, and they wrote to me to invite me to apply. I remember flying over to London and then getting the bus to Oxford for my interview. The questions were so diverse and I left thinking, ‘Okay, well, I don’t know how that went,’ but then I had a phone call from the secretary to say I’d been awarded the Scholarship. That changed my life.

‘I surprised myself’

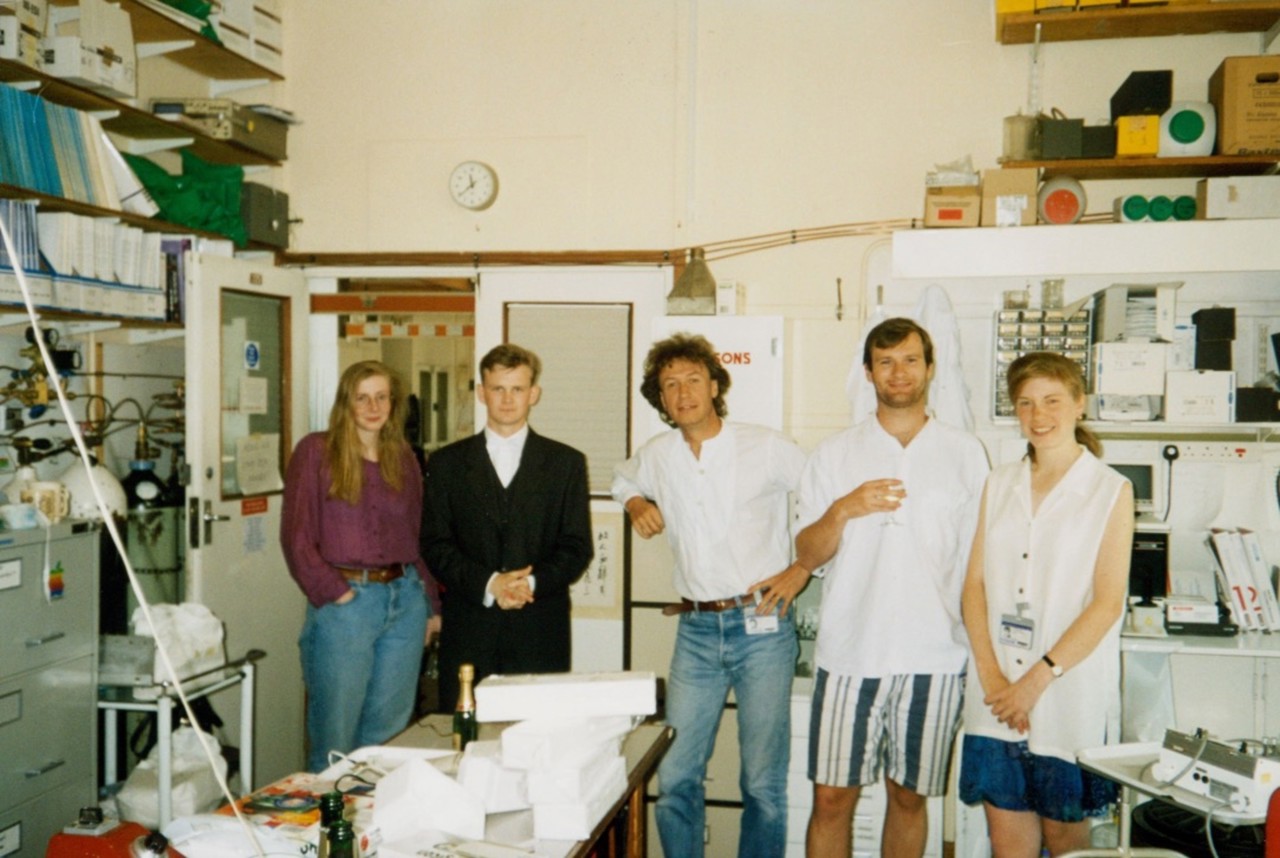

I had come to Oxford thinking that I would just stay for a year and do the MSc, but then my supervisor convinced me – and I didn’t take a lot of convincing – to convert to doing a DPhil. So, the Scholarship sort of interrupted my predetermined plan, which was to go straight back to medical school and then stay in Dublin.

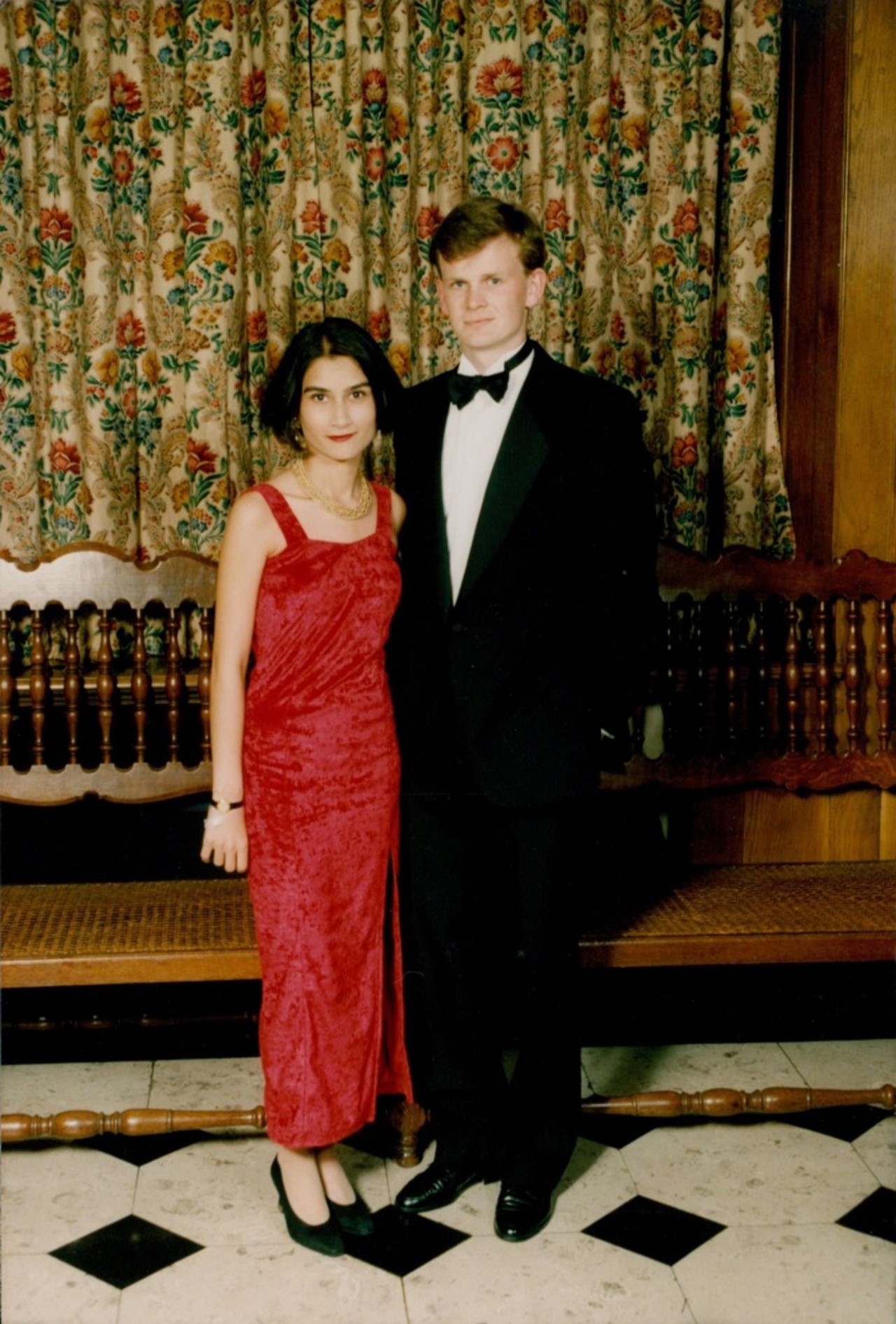

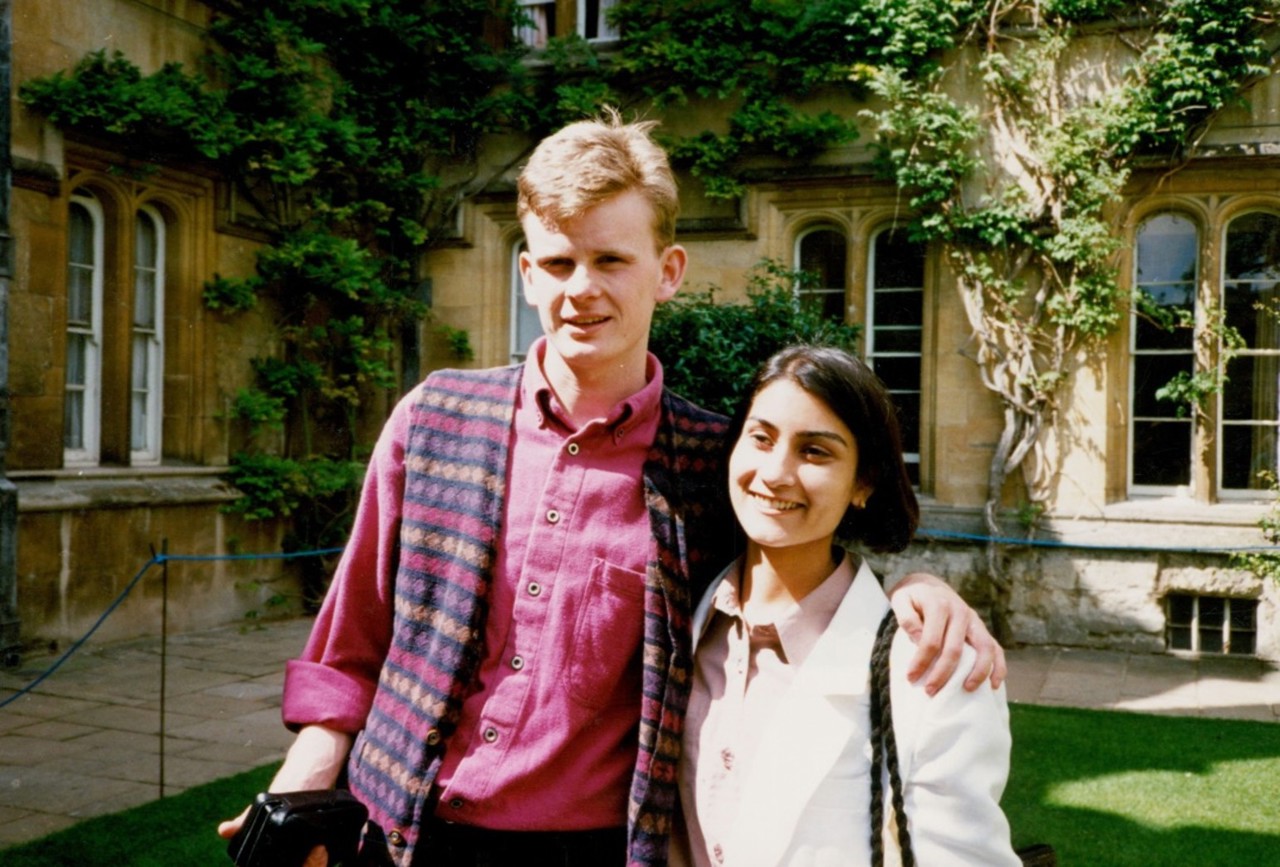

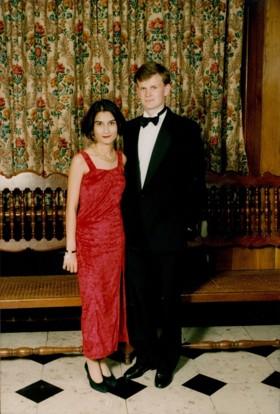

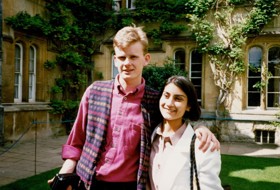

I would say that my time at Oxford as a Scholar was totally transformative in pretty much every way. I found postgraduate work really liberating, and I loved the element of discovery involved in research. And in University College, I really embraced the opportunity of being with people from every corner of the globe. I’m a fairly introverted person, and I surprised myself by making a lot of friends at Oxford. In fact, I met my wife at University College, and in 1993, for an Irish Catholic and a Pakistani Muslin to meet each other and see eye to eye, I would say that was my most significant experience at Oxford and the one which has largely defined the rest of my life.

From a professional point of view, being at Oxford definitely sent me down a very different trajectory to the one I would otherwise have followed. The Rhodes Scholarship also made me think a lot more about purpose and what I was really in this for. Quite early on, I recognised that I have been drawn throughout my life to helping others.

‘I do find all the different elements of my career interesting’

I did go back to Dublin after I had finished my DPhil, but four years later, I was back in London, in 1999. In 2005, I went to Bordeaux for 15 months to do a fellowship in the particular area that I work in, cardiac electrophysiology, and that had a major influence on the direction I’ve taken both clinically and in research since then. I have done my best to try to balance clinical work, academic work and leadership activities but I’m increasingly finding that that is quite difficult to do to the sort of level that I want to achieve in each of those arenas. I remember at an earlier stage in my life being asked what I wanted to do and saying, ‘I want to be the best in the world at what I do. And I don’t really mind what I’m doing, I just want to be the best at it.’ In retrospect, I think that’s probably an ill-thought-through ambition. But I do find all the different elements of my career interesting.

I have certainly found that the leadership piece is the most difficult one. During the pandemic, I was the clinical director for cardiovascular at our big teaching hospital in London. Very quickly, we had to shut everything down and turn the hospital into an intensive care unit that was basically like a field hospital. I think the repercussions of all the decisions we had to make are still things that we’re trying to deal with in the Health Service. Alongside the medical challenge, the hardest thing about that was trying to maintain a functioning workforce in the face of fatigue and loss of morale. That’s probably the toughest thing I’ve had to do.

‘I think it’s important to have a guiding light’

Doing the right thing is what guides me. I think it’s important to have a guiding light or a set of principles to which you adhere. For me, that’s always about trying to do the best for the other person. I think the Rhodes Scholarship is a privilege that encourages that element of you where your goal is to be of benefit and service to others rather than just to yourself.

To today’s Rhodes Scholars, I would say, don’t be afraid to engage with folks with whom you may think, ‘I have nothing in common. I have nothing to offer here.’ You can be certain that you will learn something from them and that they will learn something from you. That’s what I think networking is. It’s not self-aggrandising. It’s a way to learn, and I think that’s how you make sense of the world, by seeing it through others’ experience.