Born in Boston in the US, Margie Keeton grew up in South Africa, studying at Rhodes University before going to Oxford to read for a masters degree in modern history. Returning to South Africa, she worked for Anglo American, spearheading their Corporate Social Investment programmes to improve healthcare and education in communities, schools and universities around South Africa. The Anglo American and De Beers Chairman’s Fund was the largest and most respected Corporate Social Investment programme in South Africa. This work was subsequently taken over by Tshikululu Social Investments, a developmental funding organisation which Keeton founded and led before moving to Grahamstown in the Eastern Cape where she has been a powerful champion of educational causes. Alongside her work in early years education projects, Keeton is a strong supporter of the Rhodes Scholarship, helping over the years in selection programmes for both the South Africa at Large and the St Andrew’s College selection Committees. She has also been has been one of the selectors, since its foundation, for the Rhodes Trust’s partnership programme, the Mandela Rhodes Scholarships. This narrative is excerpted from an interview with the Rhodes Trust on 8 April 2025.

Margaret Keeton

South Africa-at-Large & Lincoln 1981

‘I was a great reader’

Both my parents were South African but I’m a dual national, because I was born in Boston when my father was studying on a scholarship at Harvard. We lived in the US for about three years and subsequently my childhood was spent in Johannesburg. When my father came back from the US, he took up an academic position at the University of the Witwatersrand and we lived on campus where my mother ran one of the halls of residence. My sister and I learnt to swim in the university pool and play tennis on the university courts and it was a very happy upbringing. I attended Kingsmead College, a private school in Johannesburg, until the family moved to the Eastern Cape in 1975. I finished my schooling at the Diocesan School for Girls and its brother school, St Andrew’s College. In the final school leaving examinations for the national private schools’ examination board in 1976, three girls from Grahamstown came out “top of the class” and I (to my surprise) was one of them. This set the rest of my academic path.

Throughout school I was a great reader and I also did a lot of sports, including netball and hockey. When we moved to Grahamstown at the end of my high school career I stayed on for an extra year Post Matric year which meant I could go straight into the second year of university.

On applying for the Rhodes Scholarship

I studied at Rhodes University, first majoring in maths and history, and then completing an Honours Degree in History. These subjects appealed to the two different sides of my nature, problem-solving on the one hand and, on the other, the chance to explore how great causes and great leaders had over time helped change the course of history. I also got very involved in student politics on campus and nationally mobilising students to vote for liberal candidates standing in what were then still national elections under apartheid and so for white people only. My inspiration came from both my mother and father. My mother was a community champion in Grahamstown from our first days in Grahamstown until her death in 2009. She initiated community projects of all kinds with an emphasis on access to education and early learning for young children and that has been a strong thread throughout my life as well. Her work continues to be celebrated in Grahamstown to this day.

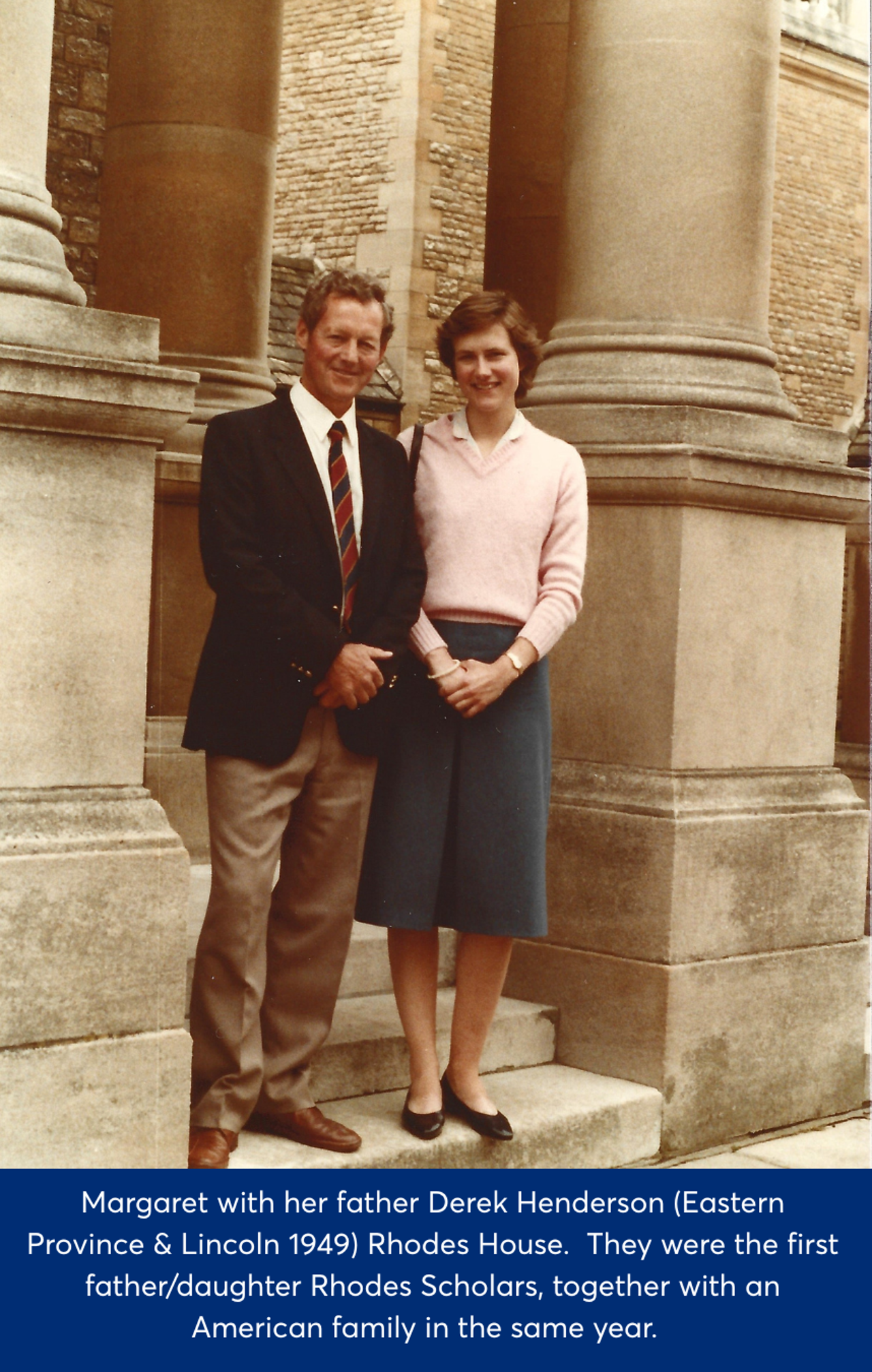

The Rhodes Scholarship was always something in my mind. My father had been a Rhodes Scholar [Derek Henderson (Eastern Province & Lincoln 1949)] and way before women were admitted to Rhodes Scholarships, my mother had been a selector for the Scholarships. She would come back from selection meetings and tell me about the young men who’d been selected, including Edwin Cameron (South Africa-at-Large & Keble 1976) who went on to play such an important role in the Scholarships in South Africa. It was all very interesting but I knew then the Scholarship wasn’t open to women, so I thought, ‘That’s just tough.’ Then, of course, when it was opened up, it very much became a goal of mine. In my first interview one of the women on the panel about whether I could cook. I knew she wouldn’t have asked a man that, but I simply said I’d done some chemistry and thought I could adapt the lessons I had learnt in the classroom to the kitchen cooking! I think the others on the panel were embarrassed by her question. As it was I didn’t really need to know about cooking as I ate in College most of the time or bought takeaways from the many vendors in Oxford. I remember waiting and waiting for a very long afternoon to hear the result after the second round of interviews. When I was one of the scholarship winners, my family were absolutely thrilled.

‘I knew what I wanted to do’

I’d visited Oxford on the Abe Bailey Travel Scholarship and met some of the South African Rhodes Scholars then in residence, so I knew this was a place I wanted to go and I knew what I wanted to do. I decided against an undergrad degree opting instead for an MPhil in History and was very glad I did. The course I did had a delightful title – “The History of the British Empire, and the Commonwealth, and of the United States”. I did a little bit of each and especially enjoyed the US History which was largely new to me. My only disappointment was that I was the sole student and so never had the chance to engage with other students on the course. But I had an excellent tutor at St Catz and I settled in quite quickly. I do remember an amazing conversation early on with another student at Lincoln. When I asked, ‘How are you finding Oxford?’ he said, ‘I’m finding the prices much more expensive than at home. The price of hashish is just appalling in Oxford.’ That was quite an adjustment for me!

I had a mix of Lincoln and South African friends. I played bridge for Lincoln and tried my hand at rowing. Studying at Oxford meant having lots of opportunities. We would often go down to London to see shows and in Oxford itself, I have very happy memories of Blackwell’s and of all the second-hand bookshops. A group of us also went out one Saturday morning to watch Prince Charles play polo in a nearby village. As I recall he was pretty disappointed with his performance but seemed to manage his temper ok. Our group of South African students staged a protest once outside the Sheldonian after people had been arrested in South Africa in some apartheid horror. It was freezing cold and we stood there with our little placards. The people in Oxford walked up and down past us and probably thought, ‘I wonder what they’re on about.’

I worked hard and prepared as best I could for the horror of taking my five Final Exams at the end in one stretch over two and a half days. By the time I was doing the fifth paper I felt like I was just floating in the hall, watching myself write. And then, afterwards, I got called for a viva with a day’s notice. I just crammed everything. I was interviewed by my tutor and two other dons and just hated it. I thought I had done very badly but after being told formally I had passed my tutor took me out for lunch and said, ‘It was an absolute formality for you. Of course you were going to get the degree’.

Attending Oxford was life changing and I will always be grateful for the privilege. It wasn’t all champagne and roses, but the tough times were important too. On the lighter side I became a fan of Thunderbirds which was very popular in the Middle Common Room at Lincoln, coped with the lingering smell of Brussel sprouts from the kitchen, and tried most evenings to keep count with the deep tolling 101 times of the Tom Tower bell at Christ Church. I learnt about the ceremony of “beating the bounds” and May Day, found quiet corners to study in at Rhodes House and the Sheldonian, and often stopped at Martyrs Memorial to ponder the scene there in 1555.

‘There is wonderful talent that is coming to the fore’

At Oxford, I had written my thesis about the historical building blocks of apartheid and I knew that I wanted to go back to South Africa, to get involved in what were the first formal anti-apartheid stirrings by South African business organisations. Of course there had been many anti-apartheid campaigns by different organisations and political parties over the years, but this was the first time Big Business took a strong, public stance. My first job was with an organisation called Urban Foundation which was trying to find a way to talk to the apartheid government and explain that the system was discriminatory and not sustainable in any sense - ethically, politically or economically. I worked for them for 5 years and then I decided I wanted something different, so I applied to the Anglo American Corporation. This was South Africa’s biggest and most liberal business conglomerate. It was a such a tough interview, and I was sure (again!) that would be the last I would see of them, but they offered me a job.

Anglo was a big business so many people on the left didn’t like them, but they had a progressive leadership and I was able to work with people across different departments, learning about different aspects of business and exploring ways in which they could do new things to advance more opportunities for black employees. Also in those days, there was a long legacy of historic environmental degradation. I suggested to one of the senior leaders I knew well that Anglo could constitute an environmental committee where people from all the operations – diamonds, platinum, gold and industry – could meet and talk about ways to mitigate the environmental impacts. He thought it was a great idea and we went ahead with Board approval. Not long afterwards, the AIDS crisis hit Africa very badly and I employed the same method, asking a senior leader if we could constitute a committee to help. This was some of the most enjoyable work I did at Anglo, and it led to my being appointed Executive Assistant to the Chairman, Julian Ogilvie Thompson for two years.

It’s a model I’ve continued to use in Grahamstown as well, going to see important people and saying, ‘There’s a problem here. I’ve got an idea. Do you think we could work on it together?’ Within that, I’ve always tried to focus on the practical, focus on the positive, rather than saying ‘Naughty, naughty, naughty’ to people involved at any level.

After my time in the Chairman’s Office I took over the Anglo American and De Beers Chairman’s Fund, South Africa’s largest and most respected Corporate Social Investment Programme. This was a wonderful time and we worked collaborately with large and small groups working to improve educational, welfare, health and environmental opportunities for communities across South Africa. Later the Chairman’s Fund was recast as a stand alone Philanthrophy called Tshikululu Social Investments which I was privileged to lead for 10 years.

I subsequently moved to Grahamstown with my husband and our son. Gavin had been my boyfriend all through the time I was at Oxford and when he was doing compulsory national service in the apartheid army in South Africa. We have been in Grahamstown since 2009 and he became an economics professor at Rhodes University. I’ve been very lucky that I’ve known people here through many connections and been able to work with them. One of our big successes for the town was the school educational campaign championed by the current vice-chancellor at Rhodes, Professor Sizwe Mabizela that has grown to the most wonderful network of effort across all sectors and communities led by another extraordinary man in Grahamstown, Dr Ashley Westaway. Together we focused on boosting the chances for black children from Grahamstown to gain access to Rhodes University. When the project started, only nine local black students a year were gaining access to Rhodes. This year alone almost 200 local black students were admitted into first year at Rhodes University, while a further 100+ local students graduated. It’s been the most marvellous collaboration, and it was all about developing resources, starting interventions at different levels to motivate teachers and students and just building community.

The Vice Chancellor and I have worked together on other civic campaigns including persuading the Minister of Justice not to remove the seat of the Provincial High Court from our city. Neither of us are lawyers but we knew that the departure of so many members of the legal profession, their staff and associated state agencies, would be devastating economically for our small town.

‘You’ve got to find ways out by creating a context in which people can emerge and change the future'

Over the years, I’ve done a lot of work on selection committees and I’ve been particularly involved with the Mandela Rhodes Scholarships. I attended a lot of meetings where Mr Mandela was present and where he shared his vision of how young people who had studied together would support one another and hold each other to account. Mandela’s hope when that first started was that it must be Africa-wide, but for a long time it was only South African students, albeit across the whole spectrum of gender, race and colour. I have seen that grow gradually and now interview students from across Africa. Every time I attend the interviews for prospective Mandela Rhodes Scholars, I come home with greater hope for our country and continent. We’ve been through some very dark times in our country, but the Scholarships have supported young people change the future for all of us.