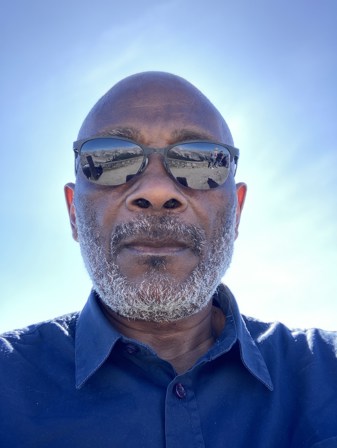

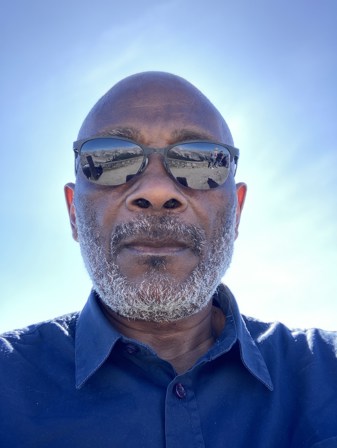

Loyiso Nongxa

South Africa-at-Large & Balliol 1978

Born in the Eastern Cape in 1953, Loyiso Nongxa is a mathematician who was Professor of Mathematics and Dean of the Faculty of Natural Sciences at the University of the Western Cape. He has also held posts as a visiting researcher at the universities of Harvard, Colorado, Connecticut and Baylor. From 2003 to 2013, Nongxa was Vice Chancellor and Principal of the University of the Witswatersrand, Johannesburg, where he was the first black Vice-Chancellor. He is currently Chairperson of the National Research Foundation of South Africa. This narrative is excerpted from an interview with the Rhodes Trust on 27 October 2023.

On growing up in ‘the province of the legends’

I was born in a village called Umhlanga in an area now known as ‘the province of the legends’, because most of the older generation who fought against apartheid are from there: Nelson Mandela, Govan Mbeki and Robert Sobukwe. Where I grew up was really rural South Africa. ‘Underdeveloped’ would be a very kind way to put it. I mean, there was no running water, there were no roads, very few schools. These places were meant to be reservoirs for cheap labour. My parents were amongst the very few people in my village who were educated. My father was a teacher, and my mother had trained as an assistant nurse, although it was a rule of the apartheid government that African couples could not both work as civil servants, so my mother had to give up work and instead, she started a village trading store.

Every family had a piece of land that they would till and harvest and people had their own livestock. The boys were responsible for looking after the livestock, so we would alternate in terms of attending school. One of the things I enjoyed doing with my friends was racing donkeys, so much so that when my parents decided to move me to a school that was further away and asked, ‘What should we get you, so you can travel to school?’ I said, ‘A donkey’. Well, they got me a bicycle in the end, but I was very fond of donkeys.

‘Mathematics is beautiful’

My interest in mathematics didn’t develop until much later in my education, because there was just no tradition of mathematics and science teaching in schools attended by kids of African descent. Our education was meant to prepare us for roles serving our communities. One of my teachers suggested I should train as a medical doctor. There was only one faculty of medicine that was open to students of African descent, and it was attached to a white university. I had been advised to do the sciences and mathematics in order to prepare for medical school. I qualified for medical school, but I wasn’t able to start in time for registration in the first year because the letter of admission took so long to get to my village and I was away when it arrived. So, I went to the University of Fort Hare to do pre-medical subjects. But the the thing is, I realised that I was hopeless in the laboratory, absolutely hopeless. I couldn’t stand dissecting dead animals. And in chemistry, you had to do titration and check for the change in colour, but I’m colour blind.

Then there was this first-year lecturer who just loved teaching mathematics, and he was energetic. I remember in our first or second test, he had set a difficult problem. He was walking around, invigilating, and he saw that I had got the problem right without struggling, and he said ‘Aha!’. His belief in me was the reason I decided to major in mathematics. What excites me about mathematics is the logic of it. If an argument in mathematics is flawed, you’re not going to arrive at the right answer. Irrespective of who you are, the correct argument will lead you to the correct answer. Mathematics is beautiful. And as an administrator, I still keep that focus on logic: ‘What is the logic of the thing being raised here, and what is the logical solution?’ So, I would say my mathematical training influences how I approach things more generally.

On applying for the Rhodes Scholarship

My decision to apply for the Rhodes Scholarship was serendipitous. I didn’t know anything about the Scholarship when I was at university, although applying for bursaries and scholarships was something I was used to doing, because I was the youngest child in my family and by the time I was at high school my father had retired, so looking for funding opportunities was second nature to me. I remember that on graduation day for my first degree, I was spotted by Thelma Henderson, who was on the selection committee for the Eastern Cape. She had heard about my good results and she encouraged me to apply and helped with the practicalities of filling out my application, like getting a photo taken and that sort of thing. She kind of held my hand. And I’m sure that Thelma was on the lookout for black kids who could be encouraged to apply for the Rhodes Scholarship, because up until the late 1970s, there had never been a black South African who had got a Rhodes Scholarship.

I have to say I was not confident that I would be a competitive applicant. Because, of course, the criteria are broader than academic achievement. I hadn’t had the chance to play sports as many others had (although I had been a sprinter), because the apartheid regime contributed very little funding for education in my area, and certainly no money for sports facilities. And there was also an emphasis on demonstrating empathy for the underprivileged. In my village, by and large, people were self-sufficient, and it never crossed my mind that somebody might be considered less privileged in that context. At the interviews, I was the only black candidate, and I remember having a conversation with another applicant where he told me how many different sports he had played, and I thought, ‘Oh, no, I don’t have a chance here.’

‘All these new and different experiences’

But I got the Scholarship, and I accepted it. Oxford was very different to what I had been used to. The obvious difference, of course, was that in South Africa, I’d grown up in a totally segregated situation. I’d never had a friendly relationship with people of other races, not only white people. And the idea of seeing white people doing manual labour was mind boggling, because in South Africa, those jobs were reserved for us. And this was a time when, in South Africa, access to certain literature was banned, and then I found myself in this place where I could get a book on Marxism, or a book on the history of South Africa, told in a way that I had not been taught when I was growing up.

So, all these new and different experiences are something that I see now, in retrospect, influenced my perspectives greatly. And academically, I had come from a very different system. I had always been the best student, and now here I was in the best institution with students from all over the world who knew so much mathematics that it used to frustrate me. Beyond that, I wasn’t able to travel as easily as some other Scholars, because the area I came from had just been made an independent state and was not recognised by more than a few countries in the world. There was even a time when I thought I should just go back home. But then I thought, what would the reception be like if I were to go back and say, ‘I’ve failed’? And so, I stayed.

‘Lending a helping hand’

I went back to South Africa to teach, staring in Lesotho and moving on Durban and then to Cape Town. And in Cape Town, I was invited to serve on the selection committee for the Rhodes Scholarship. I was amazed by the quality of the students that we interviewed. I found it so fascinating and energising, talking to these young people who had done so much with their young lives.

What motivates me now is how I can use my experience, my story, my networks, to assist people with their career development, not only in mathematics, but in other areas as well. People have created opportunities for me – it was Edwin Cameron (South Africa-at-Large & Keble 1976), whom I had known at Oxford, who recruited me to come to Wits in a senior executive role. I got such a sense of fulfilment from my work there, dealing with all the different stakeholders at a time when the university was transforming in terms of demographics.

I would say to current and future Rhodes Scholars that this focus on creating opportunities is what matters. Lending a helping hand and creating opportunities for people that maybe would not have had a chance without your contribution. It’s something that we should be conscious of and keep doing. There is still something different about the Rhodes Scholar community: it’s people who care about making a difference, in a small way or a big way.