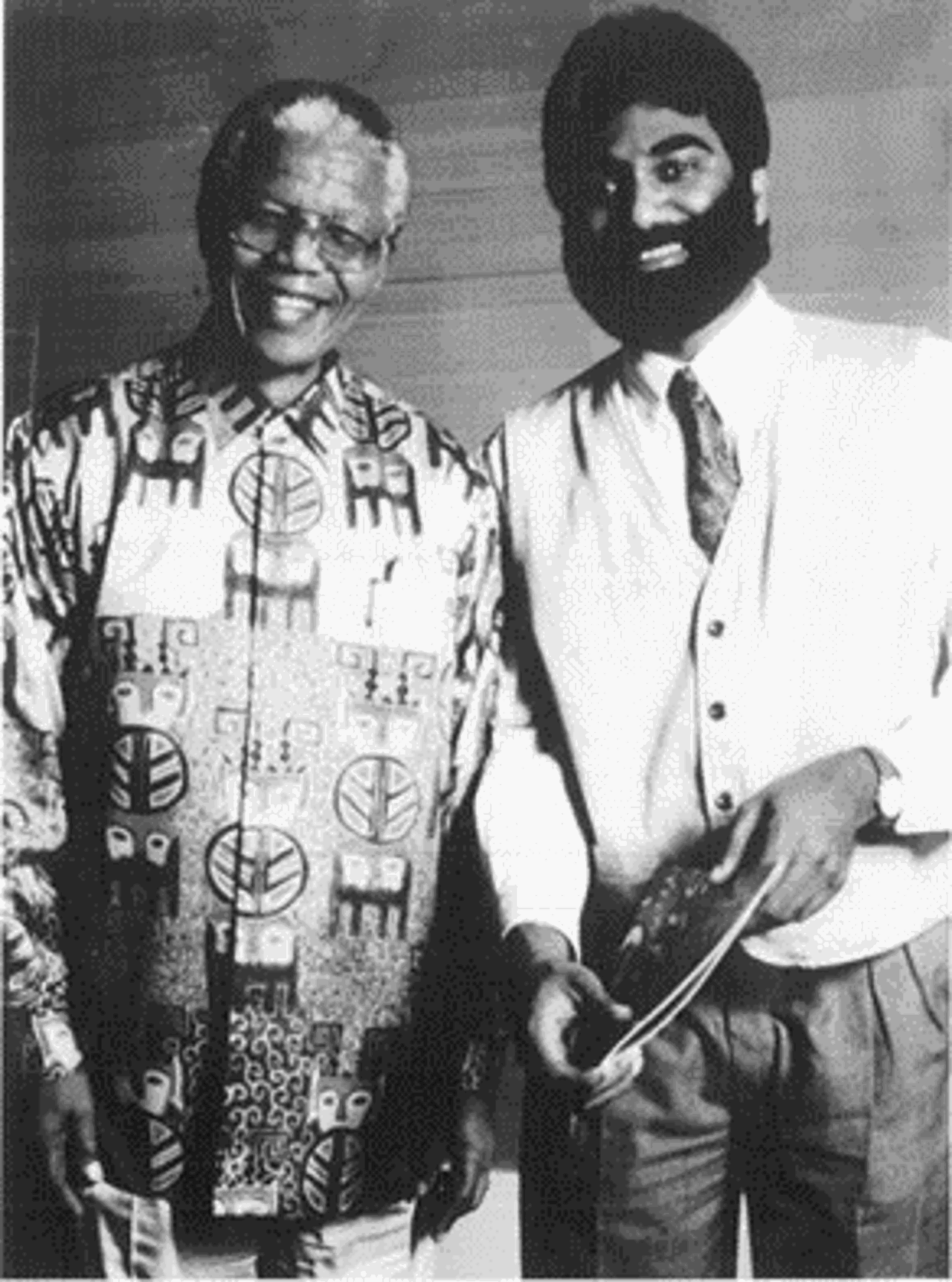

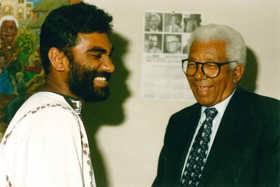

Born in Durban in 1965, Kumi Naidoo was an activist from an early age. Exiled from South Africa following his role in the anti-apartheid struggle, he continued to work for social justice and is now a human rights and climate justice activist who has held roles including Executive Director of Greenpeace International, Secretary General of Amnesty International and Secretary-General of CIVICUS, the international alliance for citizen participation. This narrative is excerpted from an interview with the Rhodes Trust on Thursday 24 August 2023.

Kumi Naidoo

South Africa-at-Large & Magdalen 1987

‘It’s better to try and fail than to fail to try’

I was born in a place called Chatsworth that was designated as one of the Indian working class townships. I was lucky to grow up with what was, relatively speaking, some diversity, because when apartheid was being implemented, the Zanzibari community in Durban was defined as ‘Other Asian’ since they were of the Muslim faith and spoke Swahili rather than Zulu. So, in my school, I had people who looked African, which was like a luxury if you think about it, because we all went to so-called ‘racially pure’ schools. Our school was known as the ‘Wood and iron school’, because it was made up of wood and corrugated iron and it stood on stilts. I didn’t have a sense of deprivation, because what you don’t know, you don’t miss, right? But I joke, and it’s true, that our school 100 metres race was never 100 metres because our sports ground was a sandy patch that was only 20 metres by 50 metres.

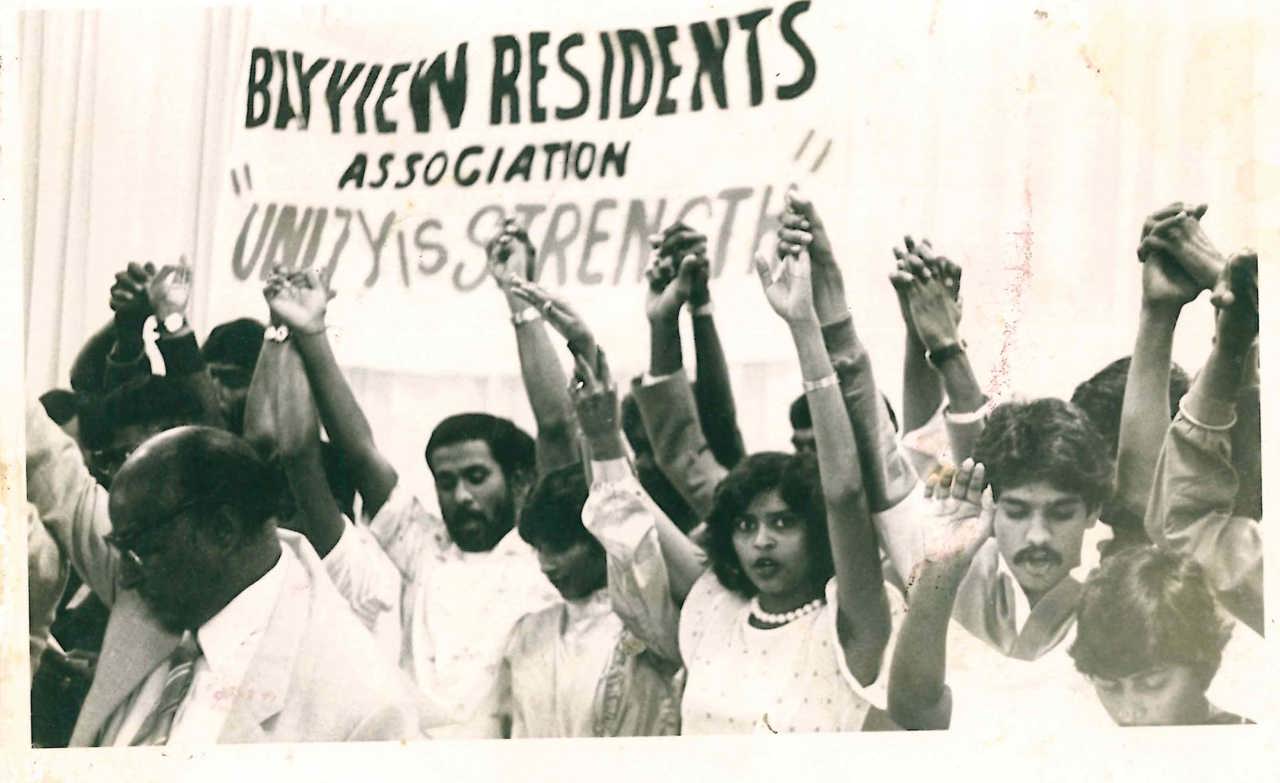

We lived as one, you know? In the boycotts and struggles that we engaged in, there was no issue about what someone’s background was. We were just in the struggle together. Chatsworth was a very violent neighbourhood, though. In a strange way, the main gangster in the area taught me about anti-racism, because, when people of other races came into the township, generally, we could delineate exactly what they were there for. The hierarchy of engagement was very clear. But with the gangsters, they all interacted as equals.

My dad was a bookkeeper. He was a very entrepreneurial, community-spirited guy and he was involved in setting up the Chatsworth football association, the Chatsworth cricket association, all of that. We became activists for our residents’ association, so we were exposed very early on to community service. My dad was a big influence on my life, but it was my mum, in terms of values, who was more decisive. There are three things she taught me that shaped my life: first, that it’s better to try and fail than to fail to try; second, that the only religion you need is that you have to see god in the eyes of every human being that you meet; and third, don’t focus on the weaknesses in other people, because you can’t do anything about that. Try to improve yourself. So she gave me a really powerful early experience.

“Use this tragedy to live your life with purpose”

My mum committed suicide when I was 15. That was a completely catastrophic event in my life. And most people who came to help, they said the trite things we all usually say in the face of grief. But one friend of my father said to me, ‘I don’t know how you recover from this, but one thing I do know is, irrespective of how sad and pained you are right now, I guarantee there are people in our country and in the world that are suffering so much more. So, if I were you, I would use this tragedy to live your life with purpose and work for dignity and justice for other people’. And that is exactly what I have tried to do.

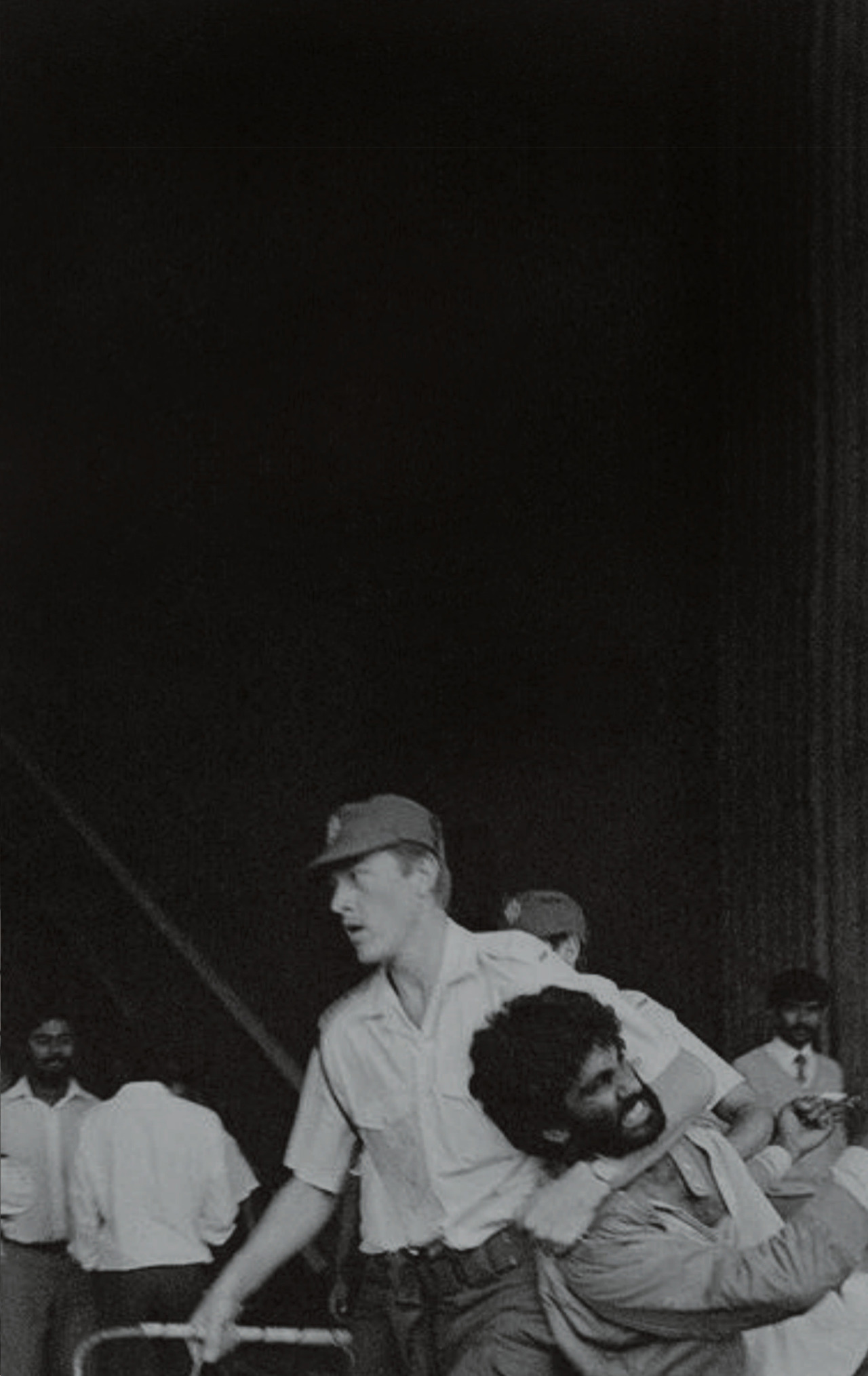

It was just after my mum died in 1980 that the national student uprising started. My brother and I got involved and we were expelled from school. Some of the progressive teachers warned me that even if I studied super hard, I was likely to be blacklisted. So, I registered for my final exam outside school and just scraped it. At university, I started off studying law but switched to political science because there was a scholarship for that. And I was having to go into hiding because of my activism, because the political police were raiding the homes of activists. And one of my lecturers basically said, ‘You’re either going to get killed or you’re going to go to prison for a long time, so get out, educate yourself, and when you come back you’ll have more skills to contribute to the struggle’. She would bring in these various scholarship applications, and one of them was for the Rhodes Scholarship.

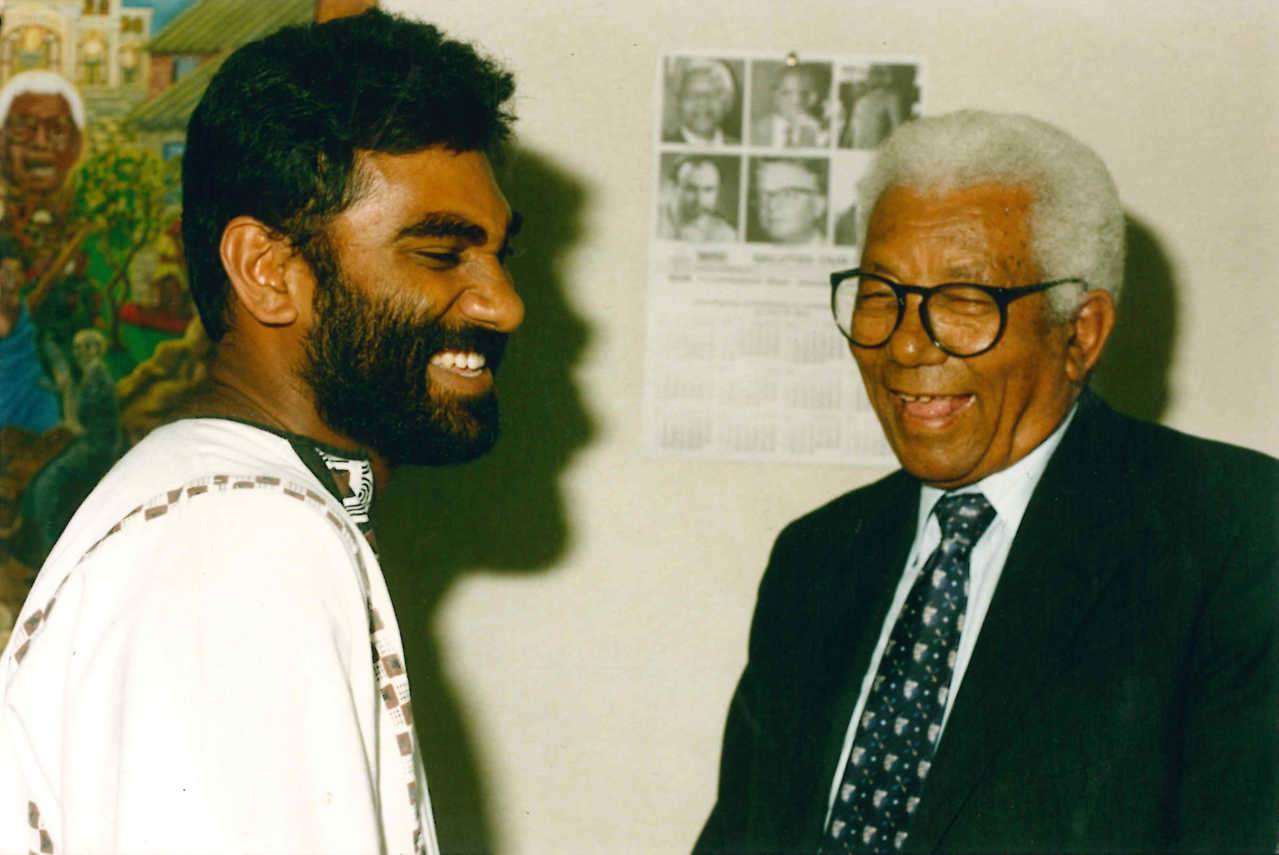

‘I was the only black candidate, and I was also the most relaxed candidate’

When I arrived for my Rhodes Scholarship interview, I was the only black candidate on the shortlist of 12. I thought ‘There’s no way in heaven I’m getting this thing’, so I relaxed completely. As far as I was concerned, I’d won already, because I got a free trip from Durban to Cape Town for the interview. I’d never stayed in a posh hotel before. It was a complete culture shock. In the interview itself, my answers were very much drawn from my political experience. And when I was asked what I thought of having a scholarship named for Cecil Rhodes, I remember saying that I would imagine Rhodes would turn in his grave at the thought of my having it, and that I wouldn’t mind that.

People talk about how difficult it is to get to Oxford, but in my case, the difficulty was a political one: I had to leave the country without being caught and arrested by the police. I adopted a disguise, and I flew via Amsterdam, because there had been articles in the newspapers about my winning the Rhodes Scholarship, so the police expected me to be London-bound. In South Africa, my friends and family helped me, and the chair of the selection committee, Tommy Bedford (Natal & St Edmund Hall 1965) also agreed to fly with me for part of the way (though then the flight was delayed, which made me even more nervous). When I got to the UK, Edwin Cameron (South Africa-at-Large & Keble 1976) had arranged it so that I could arrive in Oxford before my Scholarship started. In that way, I was very lucky, and I remember the pure shock of arriving in Oxford itself. For a short time, I stayed in Rhodes House. I remember on my first morning there, it had snowed. This was the first time I’d seen snow. And then this nice white woman knocked on the door and said ‘Can I bring you some toast and tea, sir?’ No one had ever called me ‘Sir’ in my life, and I’d never had a white woman in my room before.

My body was in Oxford, but my heart and mind were at home. I wasn’t very happy there, because it was such a traumatic time in South Africa. Every month, at least, somebody I knew was getting killed. But it was also an exciting time. I was 22 and experiencing all these new things. I went to different parts of the UK to speak about my work as an activist, and I got together with other Rhodes Scholars to found Rhodes Scholars Against Apartheid and to set up the Bram Fischer Memorial Lecture. What Oxford taught me is the skill of engaging with people who have different views from you. And sometimes, that’s a case of getting the skills to deal with bullshit, right?

‘I would be happy if we changed the name of the Scholarship’

Being in Oxford helped me understand a lot of things, and one of those things is the awesome and troubling power of British imperialism, even today. Today, many of the conflicts that we are dealing with in the world stem from those British colonial and imperialist crimes that were committed over such a long period of time. And Cecil John Rhodes is a central part of that. So, I would be happy if we changed the name of the Scholarship. Would we have a scholarship in the name of Hitler? Then why do we accept a scholarship in the name of Rhodes? When I speak, I don’t use the title ‘Rhodes Scholar’, just as I don’t use ‘Dr’ or ‘Professor’. Those aren’t the things that matter.

‘Use the opportunity to ask the difficult questions’

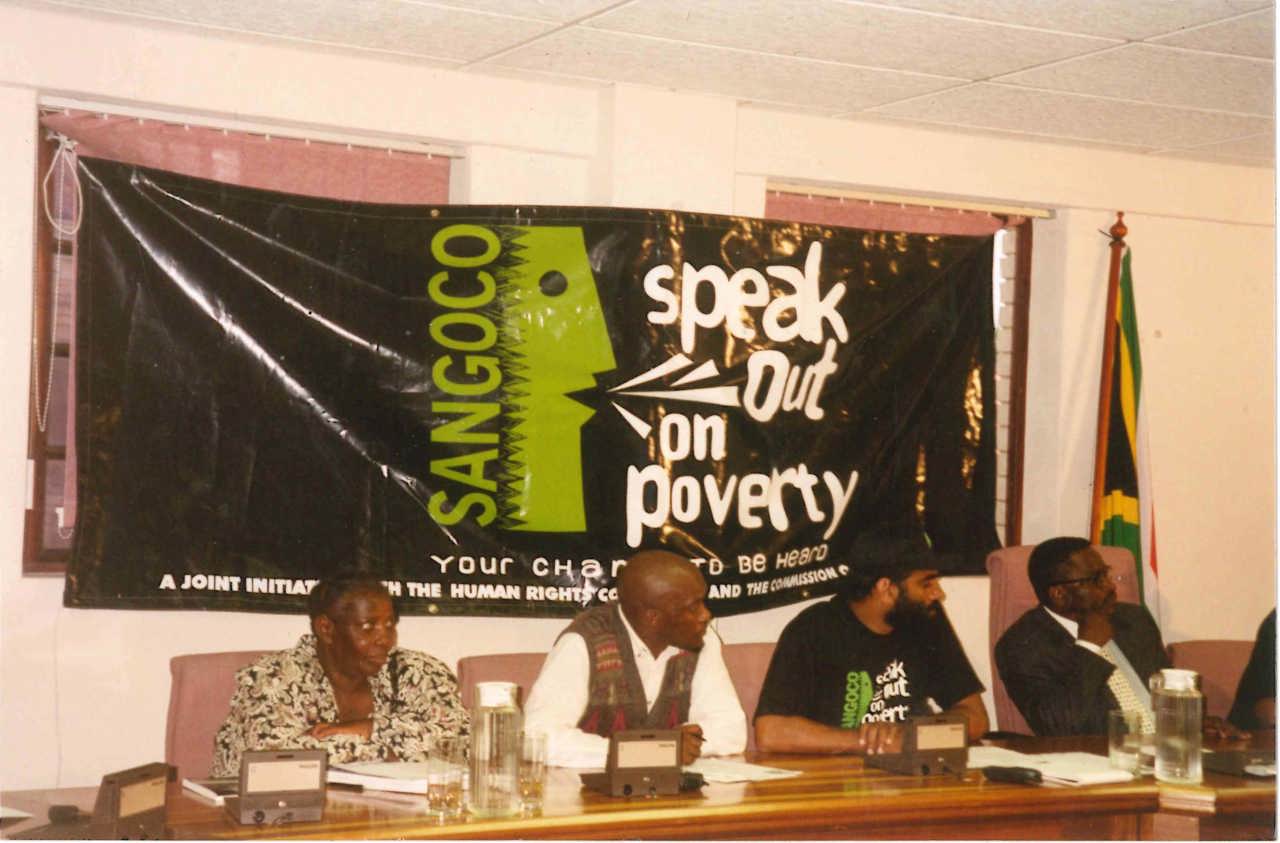

I have interacted with some of the younger Scholars recently, especially when the Rhodes Must Fall campaign started, and let me say, I am more impressed by their generation than by my generation. When I see what they are attempting to do, I am inspired. My advice to Rhodes Scholars now is this: take on the more intractable, difficult questions that humanity faces, even if it makes you unpopular. Because throughout history, society has only moved forward when good, decent, courageous people said, ‘The status quo is broken’. Yes, you’ve done well to get the Scholarship, but now it’s about how you use the opportunity to ask the difficult questions. Don’t just engage in incremental tinkering. Covid and the global financial crisis exposed all the injustices in the world, but they also showed us the approach of those in power: system recover, system protection, system maintenance. What we desperately need right now is system innovation, system redesign and system transformation.

Transcript

Transcript

Interviewee: Kumi Naidoo (South Africa-at-Large & Magdalen 1987) [hereafter ‘KN’]

Moderator 1: Sorina Campean [hereafter ‘SC’]

Moderator 2: Helen Nicholson [hereafter ‘HN’]

Date of interview: Thursday 24 August 2023

[Begins 00:13]

SC: So, Kumi, first of all, thank you for taking the time. We know you’re extremely busy, and we really appreciate you giving the time to do this interview. Just to set the stage and begin, could you tell us your full name, please?

KN: So, my full proper name on the passport is Kumaran Shunmugam Naidoo, but the name that everybody knows me as is simply ‘Kumi Naidoo’. It’s interesting how I landed there, because in my teenage years, I was getting involved in the anti-apartheid struggle. There were a lot of questions about identity, because the apartheid state defined us as ‘African’, ‘Coloured’, ‘Indian’ and ‘White’. And in the, sort of, height of the struggle, we were having all these identity conversations, because, like, somebody like me said, ‘Yes, I’m somebody of Indian origin and I’m proud of that, but I’m also an African. I only owe my allegiance to the African continent. And so, in that context, people started calling me ‘Kumi’ for short, first. It happened naturally, and then in that time, I discovered that ‘Kumi’ is the Swahili word for ‘ten’, and there is a district in Uganda called ‘Kumi District’. And in West Africa, ‘Kumi’ is a popular name in Ghana. So, yes, ‘Kumi Naidoo’ is the thing, but I prefer for people just to call me ‘Kumi’, not ‘Dr’ or ‘Professor’. Nothing. Just ‘Kumi’.

SC: And do we have permission to record this interview?

KN: Yes.

SC: Where do you call home now?

KN: Johannesburg. And specifically, Yeoville, Johannesburg, because Yeoville used to be a very vibrant community. It actually delivered the first parliament. The highest number of members of parliament came from our community and the highest number of cabinet ministers came from our community. But once the election happened, they all went to the formerly white areas, and the area has just been declining, declining, declining. And so, I’m very committed to sticking it out and trying to work in my community to actually-, we are mounting a major fight-back to address all the issues, from potholes to water to electricity to safety. This weekend, on Saturday, in my building, we have, in the failure of the utility which is called ‘Pikitup’, which never picks up anything properly, we have-, in the failure of them doing what they need to do, we’ve mobilised, like, a community clean-up on Saturday, for example. So, it’s been really interesting. We have been talking about brooms and gloves and who’s going to pay for the gloves. So, Joburg is my home, but my roots are in Durban.

SC: So, tell us a bit about where you were born.

KN: I was born in a township called ‘Chatsworth’, made up of close to 350,000 people. Chatsworth was designated as one of the Indian working class townships and I had one, like, gift compared to most people, in terms of being able to have some diversity in the way you grow up. And it’s an interesting story. Most people don’t know this. So, basically, there was a very interesting thing that happened when apartheid was being implemented. There is a community in Durban of Zanzibari descendants. So, when the British were controlling everything, they brought Zanzibari slaves to South Africa at that time. But the Zanzibari community is of the Muslim faith, right? So, when they applied the Group Areas Act which said, ‘Indians’, ‘Coloureds’, ‘Whites’, ‘Africans’ were all living in separate communities, there was an issue with the Zanzibari community, because firstly, they spoke Swahili, rather than Zulu, which was the main language in Durban, in Natal, and they were of the Muslim faith. So, some Indian Muslims in the Township of Chatsworth lobbied for the Zanzibari community to be defined ethnically as ‘Other Asian’, right? And I grew up-, in my school, I had people who looked African, right, which was like a luxury if you think about it, because we all went to so-called ‘racially pure’ schools. So, I had the benefit of having that, sort of, exposure to diversity. My best friend at the time that my mum died – one of my best friends – was a guy called ‘Bili’, and he was from the Zanzibari community, and, you know-, yes. And we lived as, like, one, you know? In the boycotts and struggles that we engaged in, there was no issue about, you know, what the background was. We were just in the struggle together.

So, Chatsworth was a very violent neighbourhood, much more violent than where I am now. We had major, sort of, gangs, turf wars. Outside my house, it was like we had exposure to reality TV way before other people did. So, you know, you’d have rival gangs coming in and there would be street warfare and, you know, you’d open our windows and you could see reality TV. And I just remember my mother being terrified when we went to the windows, because she would say, ‘If they see you looking, they might attack us’, and so on. So, I grew up in that kind of neighbourhood. I jokingly say, though it is only half-jokingly, that the main gangster in the area, whose name was ‘Karia’, which actually is the Tamil word for ‘Black’, because Karia had a very, very dark complexion, right-, but I always say that he taught me about anti-racism, because when people of other races came into the township generally, it would be-, when white people came, they were from the city council, which we used to call the ‘Durban Corporation’, right? And they were coming to check your meters, or some-, you know, they were inspectors, whether your building plans were-, so, authority coming to township was white. When white people came, they were authority over you, so, you know, their status was very clear. It wasn’t large numbers, but when they came-, then, from the African community, if women came, they either came-, when I was growing up, very few as domestic workers. Most of them came to barter vegetables and groundnuts and so on, for clothes, for second-hand clothes. So again, you know, there was a bit more equality in that relationship, but obviously, they were desperate to get their bananas, or whatever they brought, bartered for some clothes their kids. And with the smaller coloured community, if they came into the neighbourhood, usually they were partners of somebody in the neighbourhood, and so on. Because even in those days, interestingly, Indian/coloured mixing, across-, you know, even sexually, was, sort of, something that happened on a more significant scale than any other interracial mixing in my context in Durban. And so, the hierarchy of engagement was very, very clear. But what I saw with Karia, when he engaged with white, coloured, African people, they all interacted as equals. These were gangsters: white gangsters, African gangsters, coloured gangsters, everything. And you could see, you know-, like, there were white women involved in relationships with black men and vice versa, and so on. But they were all gangsters, right? Mainly in drug dealing. But actually, visually-, because outside my house was where the headquarters of this gang was. It was diagonally across. So, like, we had a wall which had these honeycomb bricks, and there would be these gaps there. And the gangsters used to put their stash in these things, and you couldn’t say anything. So, when the cops came, they wouldn’t have it on them. It would be stashed in these bricks. So, that was the environment in which I grew up. When I got to Oxford, I didn’t find many people who grew up in that kind of background, so I found it hard, actually, to find people who could resonate with my own experience. Because I also fled the country and I was technically in exile and all of that. But stay in Durban-,

SC: Would you tell us a bit more about your family? Who else was in your family?

KN: So, my dad was a bookkeeper. He had, basically, the qualifications of an accountant. He used to tell the story about how all these young, white graduates would come with their CA qualifications and so, and he would have to work under them, but he would have to teach them their jobs, because they just didn’t know how to do it. So, he was a very, very entrepreneurial, very community-spirited guy. The township we grew up in-, the street we grew up in was the first street in the township to be built, one of the first, and so, setting up the Chatsworth football association, the Chatsworth cricket association, and so on, were all things that my dad was centrally involved in. Our house-, my dad built a garage, to park his car. He had very old cars, but he took care of them, and if you didn’t have a garage, then one of the problems was – especially on Fridays, but sometimes in the course of the week – the guys would come in and break the petrol tank and take the petrol. So, that garage became the centre of the cricket association, the football association, and we became activists of our residents’ association and for our youth organisation. So, we were exposed quite early to community service. And the other thing that he did which was, I think, something that helps me now a lot, you know-, because, in the last 20 years, the temptation to gravitate to that which pays you the most, which is what we see as normal, and only to do things where you get paid, he completely turned that on its head. Because he was, like, the community auditor, right? So with it was the Muslim association, the Christian churches, the Hindu temples, the sporting clubs. They all came to him annually to audit the books. Our small, two-bedroom house used to always have, like, boxes and boxes of, you know, Mahasabha, which is a Hindu organisation. And so, we had also that other nice diversity that we had people of the Muslim faith, Christian faith and so on, and he didn’t care. He himself was a practising Hindu. But, like, he did all of that voluntarily. He never expected to get back-, sometimes, they would, like, buy him a bottle of whisky. But not much more than that in terms of compensation. But I guess those days, a bottle of whisky was not to be scoffed at.

So, then, my mum, who I would say really was the biggest influence in my life, together with my dad-, but in terms of values, I think in the end, she was more decisive, in the sense that, like, there are three things she taught me that shaped my life. One is, it’s much better to try and fail than to fail to try, and the life of an activist is mostly about struggling and failing and waking up and struggling again. The second thing, on religion-, one day, one of my favourite teachers converted to Christianity from Hinduism. And then, he went, like, completely bonkers. Like, every other lesson, he would say, you know, that Christianity was the best religion, and so on. So, because I liked him so much, I went home one day and said, ‘Ma, you know the teacher says Christianity is the best religion’, and then she says, ‘My boy, the most and only religion you need is that you have to see god in the eyes of every human being that you meet, right? And that’s all the religion that you need.’ And that, for me, is, like, such an important thing. The only thing is that as I’ve got older I’ve come to broaden it out, to see spirituality in every living thing, including in nature. And the third thing she taught me is, don’t focus on the weaknesses in other people, because you can’t do anything about it. Focus on the weaknesses in yourself and try to improve yourself, because you should try to have control about your weaknesses. So, in that sense, that was a really powerful early shaping experience. But unfortunately, she committed suicide when I was 15 and she was 38, and that was a completely catastrophic event in my life. And around that time of her death-, you know, when people lose someone, the people who come to support them are always kind, and they’re trying to be helpful, and so on. But the truth is, even me, after so much loss I’ve experienced in my life, in those situations, you can be so amazingly incompetent in terms of what to say, you know? It’s the emotional trauma of what’s going on. You end up saying the most-, either things that don’t fit, or just the trite things that people normally say: ‘God picks his favourite flower first’; ‘She’s in a better place now’; ‘She’s not suffering anymore’. You know, things like that. But in all of that time, there was a friend of my father who was involved with him in both the cricket and the football associations. His name was Uncle John Palay. And he just said to me, ‘My boy, I don’t know how you recover from something like this, but one thing I do know is, irrespective of how sad and pained you feel right now, I guarantee there are people in our country and in the world that are suffering so much more. So, if I were you, use this tragedy to live your life with purpose and work for dignity and justice for other people, because there are people who are worse off than you are.’ And that was the advice I just, as a 15-year-old, embraced. I mean, before my mum died, because of my father and mum, who were very community-oriented, we were already involved in, like, charitable stuff, in the children’s home, in the home for the disabled and so on, in the local community, but that then set me off on a course.

And then, staying with the family thing, I had three siblings, so four including myself. My sister was four years older than me and she was, like, our hero growing up, because she was older. And yes, my brother and I were, like, super-, our sister was like our god, you know? Of course, after my mum died, more so. She stepped into the role of my mum. And then my younger brother, who is a year younger than me, we grew up in the struggle together. He spent more time in prison than I did, was banned and all of that, and he’s been, like, my closest person in my family who marched the whole struggle. In fact, the funny thing was, before I went to Oxford, everyone used to refer to him as ‘Kumi’s brother’. Then I was in exile for three years. By the time I came back, he was such a prominent activist by then-, he had been to prison, he had been in police chases and so on, chasing him, hiding, and so on. When I came back three years later, everybody said, ‘Oh, this is Kovin’s brother’, and I loved it. I loved it. Sadly, after my brother, my mum had another son, but he died three days after he was born, from having been born with one lung. That had a devastating effect on my mum, and when I wrote my book last year – called Letters to My Mother: The Making of a Troublemaker – in the course of writing the book, I realised that actually, I always thought her suicide was really about difficulties in their relationship, with my dad – and that was true – but actually, in the process of, like, you know, a very, very painful process of writing for healing, which was what I was doing-, I didn’t know I would publish it, but I was doing it during Covid to just, kind of, come to terms with my mother’s passing. And I came to realise that actually, the impact of that on her and no mental health support, you know-, basically, like, even when my mum committed suicide, you know, we all were in a bad way. The doctors just used to come and give us just one injection to put you off to sleep and then would leave, like, these very strong sleeping tablets. That was all that was available to you in terms of mental health support. So, my last born in my family is my sister, after my brother who died, and she is eight years younger than me, and you can imagine, like, two brothers, especially after-, because, when my mum died, she was six . So, like, we’ve been super-protective of her, until-, she’s now a dentist and she uses her practice as a community service and does lots of voluntary things, and so on. Sadly, my elder sister Kay was diagnosed in December 2017 with brain cancer, and she was gone in a month. And so, it’s been quite a difficult time since then. Because, you know, it was like losing my mum all over again, because she had stepped into the role of my mum. Yes. Maybe that was a bit too much. I don’t know whether you wanted all that.

SC: Thank you for sharing so candidly. And just before I pass on to Helen to talk about your education, what is your fondest memory from when your family was all together?

KN: I think my fondest memory would be around religious festivals. So, the one beautiful thing about growing up-, even though apartheid separated people on race and I told you we had the privilege of having the Zanzibari community with us, but one thing that was nice was that we had people of Hindu, Christian and Muslim faiths, so we grew up celebrating everything, right? So, when it was Diwali then we went to our neighbours: they were Hindus. Or Christians, Muslims and so on, you know, with a parcel. And for Eid, they would do likewise. They would invite us to their houses and so on. But for us, we did Diwali, and even though my mum used to be petrified about fireworks and getting injured with fireworks and so on, yes, there’s something about it. And also, like, there’s this thing my mum used to do on Diwali day. You’d have a special bath. It was called a ‘three-oil’ bath, where they use coconut, and I don’t know what the other two oils were. I don’t know. Coconut was part of it. And yes, it was, like, new clothes, people coming to visit and so on. I would say, yes, around those times. It was just-, I think, for me, that is when the power of a sense of community became ingrained in me, just to see how people can rise above difference. And religious difference, sadly, is one of the most important differences people have, because, you know, some men, somewhere in history, wrote these things down in different books and we now, you know, accept every single word as if god herself or himself wrote it, you know? And so, you can’t have any debates about these things. So, when you can rise above religious difference and find commonality, it is one of the most important differences, especially now, given what’s happening in the world. If we can manage that better I think we’ll have a more just and a more harmonious world.

SC: Thank you.

HN: So, can you tell us about your education, through from your early education up to college/university?

KN: So, my first six years was in a primary school, which was not a fully funded government school. It was called ‘The Chatsworth State-aided Indian Primary School’, and it was actually set up by people in the community. And they got support from the government. I think teachers’ salaries were paid, and there were some textbooks that we got but, like, the other upkeep of school and so on-, so the school was basically made out of-, people used to call it, sometimes, ‘The wood and iron school’, because it was made up of corrugated-, you know, it wasn’t built with brick, and the floors were made of wood, wooden floors. And just one funny memory from that time. You know, now, people see me as completely contrary and anti-mainstream and all of that, but for most of my early life, because my parents were very strict, I was like the, ‘Follow the rules like you cannot believe’, right? It was only after my mum died everything changed. For the first 15 years I was, like, a straight-A student. You know, I always looked older than me. I even had certain people in the community saying to me, ‘You’ll be a good husband for my daughter’, and things like that. You know, I was so proper. So, yes, I think I lost my train there. What was I-,?

SC: A memory from the school.

KN: Yes. So then, because they used to have these wooden floors with holes in them and, like, the entire school was on stilts, meaning there would be four pillars on which the school-, so you could go underneath the floor. So, of course, the naughty boys in the class would always, like, drop their pen in the hole and say, ‘Maam, sorry, I dropped my pen. Can I go get it?’ And of course, they were going partly to come back with reports of what colour underwear different people were wearing, because they would be, like, ‘I saw this underwear’. And the school had no electricity, so twice a year they used to show movies, like Westerns and things, and they would have to run a long lead from the nearest house to the school for that day and then, like, three or four times during the movie, somebody will kick on it and then we have to run and go find out what happened and then reconnect it, and so on. But I consider that a privilege, given what my life is about, that I was exposed to-, but the important thing is, being exposed to that level of deprivation, now, when I look at it, I say, ‘Well, I get a sense of what it means’. But at that time, what you don’t know, you don’t miss, right? And so, we never grew up thinking that we are desperately poor, right? Mostly, not always, but mostly, we had three meals a day. We had more electricity then than we have now. And we had more water then than we have now, right? When you saw the difference was when you went on a bus to town and then you pass white schools and then you see, like, four wonderful school grounds, one rugby field, one football field, and so on. But our entire school, my first six years, the school ground was a sandy patch which was 20 metres by 50 metres. So, in fact I jokingly say – this is true, by the way – you know when you have, say, a 100 metres race and so on, you know, like for school sports? It never was 100 metres, because there wasn’t 100 metres to run, you know? So, then, from there, I went one year to another primary school, because that school couldn’t do, like, Standard 5, as it was then. And that school was, like, much better. It was a black school with better facilities. The state-of-the-art technology at that time was something called an ‘Overhead projector’. I don’t know if you’ll know what that is. You don’t know what an overhead projector is.

HN: Where they have the, sort of, sheets.

KN: You put the transparency over-,

SC: They had them when I was in school.

KN: Yes. So, that was, like, the height of technology. Oh, no, sorry, it wasn’t in my primary school for that one year. But that year, for me, was such a transformative year, because that was the year-, my mother was still alive, and I was beginning to, like, push back against being, you know, the goody-two-shoes. Because then I met some friends at school who were, like, kind of, all doing well at school and all, but, like, were questioning everything and so on. And then, by the time I get to high school, which was the Chatsworth High School, which was, like, a really highly respected school-, it had, like, students who would do well in the national exams and things like that, so parents even from the posher area in the township would bring their kids to that school and drive them there, because it had a reputation. So, very, very privileged. And the teachers then, my god. Sarah, the teachers were committed, in a way-, I’m not saying that there are not committed teachers today, but it was a norm to be a committed teacher, whereas today, when you look at it, when a teacher does do something extra, everybody goes, ‘Oh, wow, what a great teacher’, right? And so, you know, like, my teachers, I owe such a big debt to them, you know? Because, like, they shaped my values. They struggled with us, because my brother and I were, like, the two top students in our standards, and then suddenly, the 1980s-, so, then, when my mum dies in 1980, it was also two weeks later the national student uprising started, and so, when my brother and I get involved and we get expelled from school, like, you can imagine the teachers were, like, you know, ‘These kids. Their mother died and now they’ve sacked this. Destroying their education’, and so on. So, when we got expelled, we took the government to court. It was 500 of us. We took the government to court, and we won our court case and we got reinstated. That was, like, the penultimate year of school. But then, we won our court case, but they didn’t allow us to write our exams at our own schools. They made us go to another school, because they didn’t want us to contaminate the students, and so on. So when we passed, those of us who passed, they had to take us back, then, the next year. I went back to school, but then, some of my teachers-, many of them were still very supportive, were willing to-, they were giving us, you know, banned leaflets, and all of that. But the school management and a few of the senior teachers were so scared of us. Like, I’ll give you an example. I had an English topic, which was-, what was the composition? Yes: ‘Compare and contrast two people that you admire.’ And I did it on Mandela and Gandhi, right? And I remember the English teacher coming in and just throwing the thing. He said, ‘You want me to go to Robben Island? You give me this kind of junk to mark. You want to go to Robben Island, you go. I’m not going to go to Robben Island. Do another topic.’ You know? And then, the progressive teachers in school came and said to me, ‘Listen, there’s a good chance, even if you study very hard and you get all As, they’re going to blacklist you.’ So they advised me to leave school and go and quietly register for the exam that – you know, adults who drop out and go back – where they were not monitoring it so much.

So, for my final year, I self-taught myself, registered for this exam, with at least six close friends who were in the same situation, and then we wrote the alternative-, it was called the ‘Joint Matriculation Board Exam’. And I just scraped it, scraped it. Like, I just got the basic marks to pass it, because basically- but to be fair, even then, for my physics, for my biology, for English, we either had teachers from our school who quietly, at night, after they finished school and, you know, their normal duties, would come to a place and teach us. And they would, like, normally say, ‘Please don’t tell anybody we’re doing it’, and so on, but they were preparing us for that exam. So, I made it into university. Like, probably just made it into university. I can guarantee you this: no other Rhodes Scholar who had such bad grades as I had, in either my high school or my university, right? I’ll come to that in a second, about the university. So, I get to university, yes, study law, BA Law. What I know about law is very dangerous, not much. I was breaking it most of the time. So, I managed to finish my BA Law, which is a three-year degree. And then, I didn’t continue with law. Because, you know, I could see my father was struggling financially, because by then, my brother was also at university. So, then, I got, like, a scholarship to do Honours in political science. There was a scholarship that came with it, so I left law and went to political science. So, in December of 1986 was when the army raided my house, while I was in Cape Town being interviewed for the Rhodes Scholarship. And my folks at home, when I called them, they said, ‘Don’t come back’. But, like, I was in Cape Town, I had no money. You know, I could stay with people a little bit. I was only 22 years old. So, I eventually thought, ‘Shit, I’ll go back to Durban. Durban, I know a lot of people, so I can know where to hide’, and so on. So, then I got back home and discovered that there was a national raid on 12 December 1986, and that raid was done with the army and special branch, like, the political police, like the Gestapo. And then I had to go deep underground. But for a lot of the period from June ’86 to March ’87, I was living underground. Most of us were. You know, changing places, disguises, all of that.

So, then I start talking to the Rhodes Scholarship people. So, Edwin (Edwin Cameron (South Africa-at-Large & Keble 1976)) was the one who broke the news to me that I got the thing, and it was so funny, you know. Edwin-, I’m so fond of him, right? He basically said-, I was meeting the day after, you know, I got the Scholarship. He asked me a question. He says, ‘So, which college do you want to go to?’ And guess what I said? I said, ‘No, I don’t want to go to college. I want to go to university’, because in our language, you go to technical college, teacher training college or university at that time, right? And so, I think poor Edwin must have thought, ‘Sure, I think we made a mistake with this guy’. And then he had to explain to me about the college system and so on. Because one of my lecturers basically said, ‘You’re either going to get killed or you’re going to go to prison for a long time, so get out, educate yourself, and you can come back and you can contribute to the struggle with more skills.’ And she was a professor and a thinker and so on. So, she would bring these various scholarship applications, and one was-, the French government was offering one. I got that and I got the Rhodes Scholarship, and to be honest with you, I often regret not having taken the French one, because then I would have been able to speak French, you know, fluently, and that would help me more with my activism on the African continent at the moment, and so on. So, then the question was-, I still had to write one exam, you know, for my honours, which was two months after the army raided our home. And the question was, should I write it, should I not write it? And then, I spoke to the Rhodes Scholarship people and they said, ‘Listen. Technically, you will probably get in without that, but, you know, the standards are high. If you can do it, I think you should do it. So, then, I go and speak to the same professor who advised me to apply for the scholarships and she said, ‘Okay, here’s the deal’. Bear in mind our campus has three entrances, and the army is at all three entrances, and I’ve got a very common surname by Durban standards. So, the army used to be there, stopping the cars and asking people, ‘Is there a ‘Naidoo’ here?’, ‘Is there a ‘Naidoo’ here?’ Every other car had a ‘Naidoo’. So in any case, my professor – her name is Marla Singh. She’s still alive. She’s great – she said, ‘Okay, no. I’ll negotiate with the university that they put a secret venue on the campus, and we’ll have special invigilators.’ So, I had to write four papers, and all of the four papers, I had to come through the roadblock on a January, Durban, super-hot time, and I had to be in a very sophisticated disguise. So in those days, I only wore tackies and t-shirts and jeans and, you know, I had one suit that we bought for one family wedding, so I used to wear that suit – a three-piece suit. Boiling hot – I would have an insurance salesman-, like, a briefcase, and I would go in with a white academic whose house I was hiding in, and then another academic who was Indian would take me out, each time. So, the cops would go to the earlier announced venue where I was supposed to write. And thankfully, there were only two of us doing that course. So, there was another woman, Jenny Maraujo who would be there, and my seat-, they would hand out my exam paper, and I would be marked ‘absent’ there, and then the cops would leave, and then meanwhile, I would be on the campus, because I had to be on the campus, otherwise-, they wouldn’t allow me not to be. So, I would write that at a different venue, and then after that, I would have to get out of the campus very, very quickly. So, like, this one lecturer would be, like, as if she was in a spy movie, you know? Because her life-, anybody helping you could get five years for aiding and abetting. You could get up to five years for aiding-, even just providing a place to hide, giving you a ride, and so on. So, somehow, I actually managed to pass, and actually got a summa cum laude. Because, you know, it was the first exam I really studied for, because I was in hiding. Nobody could see me. All I could do was study. So, yes, those were the best grades I ever got at university, thanks to the security-, in fact, then, when I fled, my younger brother ended up in prison for close to a year, and he wrote his exams in prison, and he, like, aced it. He got all As. The only time he, like, got such good grades. And my father says jokingly to me, ‘You know, it might be a good idea if Rini gets arrested around June/July, so the last… is imprisoned to really get good grades.

So, university was amazing as a learning experience, right? Most of my learning was outside the classroom, rather than in the classroom, but you know, I really took the studies seriously. I mean, we crunched a lot, to scrape it each year. And then, while I’m writing the exams, I’m negotiating with the Rhodes Trust people in South Africa, so the Rhodes selection committee, about, can they help me? And now, they’re all white people, that I’m dealing with, right? Because imagine that their interactions were so limited. Like, when I went for the Rhodes selection, there were 12 candidates, and I was the only black candidate. Actually, I have a chapter in my book called, ‘The only black candidate’, which is about the Rhodes selection process. And then, on the selection committee, there was one African woman, called Elizabeth Mokotong, who now-, up to today, she is like my mother to me. Like, she spoke at one of my book launches, and everything. And I remember the question she asked me. She said, ‘Kumi, why do you think you’re the only black candidate who made it here?’ And I said, ‘Firstly, to be honest, I never even knew the Rhodes Scholarship existed, and Oxford University. The only thing I know about Oxford was Oxford maths sets and the Oxford Dictionary.’ I never had any reason to think about Oxford other than the dictionary and the maths sets. You know, those geometry sets? Then I said, ‘Well, if my professor hadn’t asked me to do it, it would never have happened, but I’ll be honest with you, I had lots of hesitation about applying, because of what Rhodes’ legacy means, and I think one of the reasons people like me who would qualify for it and who would not apply is because they have reservations about-.’ And then she said, ‘How do you feel?’ I said, ‘Well, if you’ll give it to me, I would imagine that he would turn in his grave, that you’ll give it to me, so I wouldn’t mind making him turn in his grave.’ Something like that. Some answer like that. And then, another question that I should tell you that I still remember was-, the guy that was Chair of it was a guy called Corbett – Jim/James Corbett, I think – and he was, like, the head of the highest court. And I think he’s the one that actually swore in Mandela, when Mandela was elected. So, he asked me, ‘So, Mr Naidoo, if you were made Minister of Education, how would you solve the problem of education.’

And the important thing was, when I got there and I see all 11 candidates white, selection panel 99% white-, and of course, everybody is trying to be nice to me, right? Whether they had racist inclinations or not, they were all feeling the need to be nice to me, right? Because they were going to assessed. Because, you see, part of the assessment is dinners and things to see how you get on and all of that, right? So everybody wanted to show that, ‘Oh, I might be a white South African who was brought up under racism and privilege, but I need to show that when I go to Oxford, I can interact with people of different races and different backgrounds, and so on. So, I was the one, sort of, person they could show how great their skills were in terms of engaging with other people, right? So, everybody was very nice to me, and I’d never been among so many white people in my life, ever before. It was, like, an intensive two weeks. It was just white people. And so, when he asked me this question about education-, so, once I heard which universities they went to, what their grades were at high school – you know, because they were telling me all these things – what their grades were at university, I’m, like, ‘I got Cs and Bs, best grades’, I’m, like, ‘There is no way I’m going to get it.’ But the truth is, even before I got there, to the interview, I was, like-, as far as I was concerned, I had won already, because I got a free trip from Durban to Cape Town for the interview. So, like, just getting that trip to Cape Town, and the first time I’m staying in a posh hotel and all of that. In fact, it was the first time I encountered a bidet. Do you know what a bidet is? For me, that was just, like, completely-, coming from Chatsworth, you know, we had an outside toilet for the first six years of my life. So, like, a bidet is like you cannot imagine, and I messed it up. I was just experimenting. I opened it and shot the thing in the roof, and so on. Like, it was a total culture shock for me, right? So, when I get there, I’m, like, ‘There’s no way in heaven I’m going to be getting this thing’, right? So, I was the most relaxed candidate. I was not only the only black guy, I was also the most relaxed candidate. I’m like, ‘Okay, there’s absolutely no way I’m going to get this. Let me just not stress myself out.’ So, when the question was asked about education, I gave a very, very political answer. All my answers were political. When I say, ‘Political’, based on my values. So, then I said, ‘Well, thank you very much for the question, but I must say that’s a rather naïve question, because even if you took somebody with the compassion of Gandhi, the intelligence of Einstein and the revolutionary zeal of Che Guevara and combine all of them into Education Minister for this country, they’ll never solve the problem, because that question presumes that the education crisis exists outside of the broader political crisis. So, if you don’t change the fundamental issue that the majority of people have no voice in this country, whoever you put as Minister for Education is never going to solve the crisis in education.’ Because, you know, people are not going to school in large numbers. Boycotts, protests, and so on. So, it was a time of, like, real, real heavy resistance, so-, and young people were so angry. We all wanted to go join the liberation struggle, you know, outside the country, join the armed struggle. Not all, but a lot of us wanted to. So, anyway, when Edwin calls me the next day to say I got the thing, I was, like, ‘Jeez, there must have been a mistake’. And so, being in Oxford was a total culture shock. Jeez, you cannot imagine. I could tell you such funny stories. But my early education was requested, so I gave you primary school, everything, right? Do you have any specifics, comebacks, on any of that?

HN: No, I think that’s great.

SC: We can move on to time at Oxford. So, you arrived in the UK in exile?

KN: Yes.

SC: How was that?

KN: So, the plan was, I had a hired car. One of my comrades in the trade union movement had hired a car, and I was going to drive to Joburg. And then, I had my final underground meeting in Durban with my contact telling me who I must contact when I get into exile, you know, if I make it out and so on. Most probably, he was a more high profile activist and I speculate that he was followed there. And they knew-, he had been in and out, so they were probably just checking who he was meeting with. So, then, I picked up a tail, and I noticed a tail, a car tailing me. And, you know, we knew the special branch agents’ cars. You know, they were not normal cars, but we kind of knew-, they used to use these white Toyota Corollas a lot. Anyway, I figured that out, so I say, ‘Okay, I have to disappear’. But anyway, to cut a long story short, while escaping them, I lose them, but I crash into a Mercedes Benz. And as my brother said, ‘If you’re going to crash into any car, crash into a Mercedes Benz.’ So, it’s all the details I have in my book, but then, I have to dump the car. So, my brother and some close comrades of mine have to do this elaborate thing, because now, it’s a hired car, right? You imagine the cost. Just thinking about what it would cost was just, like-, so we said, ‘Okay. What we have to do is make it like the car was stolen.’ So we did a whole operation where we pulled out the radio to make it seem as if that’s what they were trying to go for, that we dumped the car in, you know, in a posh area, and then I get back to my hiding place. My brother was not with me at that time. I get there, tell my brother the story. I had this whole thing figured out, sorted out, and then he starts asking me, ‘Did you check the fingerprints on the gear lever.’ Not gear lever: petrol tank lever. ‘Did you wipe the fingerprints underneath the lever of the thing?’ And, like, my brother was a much better underground operator than I was, so basically, it was half an hour where he insists, at 2 a.m. in the morning, ‘We must drive back to the car’. We go there, he does everything again, everything, you know. Like, even the petrol tank, he says, ‘When you filled, you must have opened it. Did you fill it with petrol?’ I said, ‘Yes’, then he goes, he wipes that. The car was then found the next morning, and thankfully, you know, my friend whose name it was in, reported it stolen.

So, we got out of that, but then I had to fly to Joburg. So, now I’m operating with a disguise for the exams and so on, which-, a very prominent playwright in our country who is late now, his daughter was one of my closest friends and comrades: Pregs Govender, whose father, Ronnie Govender, was, like, one of the most respected playwrights in our country and he knew about theatre and so on. So, he came and he figured out the disguises I should use at different moments. So, he came up with a thing called the ‘Lionel Richie lookalike’ disguise. So, basically, I, in those days, used to have a massive beard and long hair, so he takes me at 5 o’clock into a salon called ‘Sensation’ – I remember it – and this woman came who was helping out to do the disguise, she acted like she was planting out a limpet mine or something. Like, she was so nervous. And I was on this permanent sleep deficit, so I fell asleep, and then, when I woke up, I see this person in front of me. I’m wondering who that person is. I couldn’t recognise myself. She had taken off my beard clean. That alone would make a big difference. Most people wouldn’t have recognised me if I just took off my beard. She had cut my hair shortish. That I remember, her cutting my hair, and I remember her putting my head in some machine which I didn’t understand. I’d never seen that machine before. And basically, she permed my hair, like a fine perm, and all I can remember is the stink of the chemicals that you use. It was just awful. And then Ronnie picks me up. He takes me to an optometrist friend who gives me those old, professorial glasses. You know those old glasses that we used to wear? And he put a dummy lens, just like, you know, no power in it. And I can tell you, my aunt, whose house I was hiding in at that time, my elder sister, and my girlfriend at that time, all of them didn’t recognise me. Only when I opened my mouth, they could recognise me. So, I was able to move.

But now, when I’m fleeing the country, when I’m moving now from Durban to Joburg to get to Oxford, I no longer can drive, because I’ve messed it up with the car, right? And my brother was also, like, ‘No, no, you’re putting yourself too much at risk.’ And the better risk was for me to fly, because in those days, you didn’t have to show ID at the airport. You probably can’t even imagine that. Do any of you remember times when you didn’t need ID for local flights? So, basically, I didn’t need it. So, basically, Pregs Govender, who is one of the leading feminists in our country, whose father was the one I said, left me at the airport. And then, I took a risk. One of the four Rhodes Scholars that I was selected with was a guy called Ian Lowitt (South Africa-at-Large & Merton 1987), and I just said, you know, ‘Let me take a chance and call him’. Because the thing is, if I called any other comrade of mine, they would be monitored, you see. And Ian was somebody I spoke to, and we connected well. And then, anyway, I stayed with him for a night, and the next evening, I go to the airport. The flight was at 5 p.m. and I was scared to fly alone, because if I got arrested and nobody saw me, then I would just disappear, right? So, Tommy Bedford (Natal & St Edmund Hall 1965), who was on the selection committee – one of the people – said he had a business flight. He was going to be on the same flight. Then the flight gets delayed by eight hours, and he had a business trip, so he had to change his flight and go. So, when I get there, he says, ‘Hey, I don’t know whether you’re going to be safe’. And then, I tell you, the paranoia of that time was that you think, ‘The flight must be delayed because they’re waiting for the special branch agents from Durban to come and identify me’. You know, the paranoia. We used to say, ‘Just because you’re paranoid, doesn’t mean the bastards are not out to fuck you up’. Well, that’s how we said it, so-, so, then, anyway, they put us in a hotel. They picked us up at midnight and 2 a.m., the flight makes it out. I go via Amsterdam. That was the other thing: the flight was through Amsterdam, so that-, because there were articles in the newspaper when I got the Rhodes Scholarship, lots of articles in, especially, the Durban newspapers. So, the special branch knew that I was London-bound, potentially. But before I left, I had to do something very interesting, which is, I had to write an affidavit, which said, ‘My name is so-and-so, I come from a working-class background, I’ve got this opportunity for this scholarship.’ This is-, I flee on 3 March and my case – my next court appearance – is on 11 March. And I say, ‘I’m going to Oxford to tell them that there is a chance that I’m going to be arrested and for them to hold my place’, right? So, that affidavit was there with my lawyer, so that if I got arrested, the lawyer would say, ‘Listen, here is the affidavit. He was not fleeing. He was just going to speak to Oxford and then come back. Obviously, once I make it out, he’s going to throw the affidavit in the bin, right? Which is what he did. So, I made it out. I get to Oxford.

SC: So tell us about-,

KN: Arriving?

SC: Being in Oxford, studying in Oxford.

KN: Hey, listen, I could tell you some things you don’t want to know. You’ll have to censor it, right? I’ll tell it to you as it is, as I experienced it.

SC: Please do.

KN: So, I land at the airport in London, and first time now, right? And I have that small paper from Rhodes, saying that, you know-, and they say, ‘But doesn’t your Scholarship start in October?’ Oh, no. Edwin Cameron. He was advising me what to do about everything, right? He was writing to me. So, he, then, when he knew the date, he said, ‘I’ll plan my thing so I’ll be there when you arrive.’ So, he had a fellowship in Harvard, and he made sure that the day I arrived and the next three days, he was there. So, he was not around when I landed, specifically because he had a dinner outside Oxford, but the next morning, he took me around, introduced me. But let me stay at the airport. So, the first thing was, like, the people at the airport now suddenly saying-, but then they call Rhodes House, but Rhodes House had been alerted by Edwin about my early arrival, and Edwin made arrangements for my stipend to start, like, in March even though it should only start in October. So, I can’t tell you the culture shock of that, just that bus ride from Heathrow to Oxford. It was just something. And you know, one of the images that I remember, I remember seeing a band of Sikh workers, all Sikhs, doing a construction on the road. I was, like, ‘How did this happen?’ Like, a disproportionate number of Sikh guys doing a road construction job on the way to Oxford. But the beauty of the greenery and all that was quite something, and I already had got so homesick, because it reminds me of-, because I didn’t tell you, you know, the Midlands and North Coast and South Coast, it had that same luscious green kind of thing. So, I was going to stay at Rhodes House which was-, in itself, you cannot imagine what a culture shock it was for me. You know, from growing up in a two-bedroom house, and suddenly, you’re going to spend a night in Rhodes House.

So, when I arrived, the Warden then was a guy called Robin Fletcher, who had a great affection for alcohol, right? And I couldn’t follow, sometimes, exactly what he was saying. But on the face of it, having not had much interaction with white people in my life, he was very polite and welcoming and so on. So, they put me on the top floor in Rhodes House, and then they put my name on the second floor, next to the telephone. On one side, they wrote ‘Kumi in’, and on the other side, they wrote ‘Kumi out’, and they kept turning it around, whether I was out or not, because once the word got out that I had fled, the articles appeared in-, oh, once I announced that I got there, all the newspapers carried, ‘Rhodes Scholar pops up in London’, ‘Activist gets out of the country’, that kind of thing, and people are sending me-, so, the families would be sending to their kids in Oxford, so they were all finding out about it, and they were calling Rhodes House to say, you know-, especially the progressive South Africans, who wanted to see if they could help me and so on. So, I was very happy there, you know. I was having breakfast-, oh, the first morning – I’ve told this story many times in speeches – the first morning. So the Warden calls me about a week later. I’m, like, thinking, ‘Okay, I’m chill here’. Safe place, you know. Even if there are agents and all of that, I’m on the third floor. I’m, like, super-, so in the second week, the Warden calls me: ‘Kumi, I’m sure you want to find a place of your own that you can call home’. It’s another way of saying, ‘Time to leave’. When I told my English friends this, they said, ‘No, you should have told him, “No, no, no, I’m very happy here. In fact, I don’t mind spending all my three years here at Rhodes House.”’

But my first night was quite a thing, right? So, I arrive at Rhodes House. Wonderful Mrs Jinny Fletcher, his wife, opened the door. I get in. So, I didn’t grow up in a culture of having soup. Soup was just not something that we had, right? And so, I had my first soup, and it was the first time I had encountered these things called ‘Croutons’, you know? And then visiting was Mr and Mrs Fletcher’s son, who was from the army, and, like, that freaked me out. Like, you know, because now, the British and the Americans were collaborating with the apartheid regime and so on, and suddenly, I arrive here, I’m on the run, and there’s a soldier, all of that. But he was fine. And then, I go to sleep. I was so exhausted-, imagine, for about three days, I hadn’t slept at all, right? The adrenalin of fleeing the country and the plane delays. So, I didn’t even close the curtains and I didn’t even take off my clothes, you know? I just took off my thing and I just collapsed on my bed and covered-, I slept for 12 hours, and then eventually, there was a knock on the door. And the worst thing for me was a knock on the door, because I’d been on the run for so long, and then this big knock comes and I panicked, and then I opened my eyes. It was 4 March, and it had snowed the night before. And, you know, Oxford has this thing called the ‘Dreaming spires’, or whatever, and it’s caked with snow, right? So, the first thing I see is snow. I’d never seen snow in my life before, right? I’m, like, in a state of shock. Where am I? Where did this white snow come from? And then, the door opens, and a very nice – race is important here – a very nice white woman says, ‘Good morning, sir. Can I bring you some toast and tea?’ I’d never been called ‘Sir’ in my life. I’d never been offered breakfast in bed before in my life. I’d never had a white woman in my room before. And the snow-, I’m, like, ‘Shit. Where am I? Did I die? I’m in heaven.’ Seriously, I was, like-, I must have looked at her with such derangement in my eyes that after a minute she said, ‘Thank you, sir’, and she left without a word coming out of my mouth, yes? So, anyway, she became a friend after that. Like, I was there for that week and we started chatting, and so on.

SC: Tell me a bit about how you went about choosing your course.

KN: Conventionally. Conventionally. Because I did an honours, and then I knew that the next thing I must do is a master’s, because I had no-, Now I think about it, I probably should have done something specifically in economics, right? But, like, because I’d finished the honours in political science, the next step in South Africa would have been doing a master’s, and then a doctorate. So, I started doing a master’s in political science, and then after one year, I converted that to a DPhil programme.

SC: What was it like studying there?

KN: See, my physical body was in Oxford, but my heart and mind were at home. So, every death, every detention of people I knew and loved and worked with and all just, like, hurt me a lot. But unfortunately, I didn’t have a happy time at Oxford, because it was a such a traumatic time for-, you know, every month, at least, somebody I knew was getting killed, you know? But it was also exciting, right? You know, I was 22. I’m experiencing all these new things. And then, like, I couldn’t find people who had the same, sort of, vision of the scale of societal transformation that was needed globally and in my own country. Then suddenly, I see-, I get there in March, right? Suddenly, I see, ‘Shoo! This is great! Everybody is getting excited about May Day.’ I didn’t understand, how could all these people be so excited about International Workers’ Day? Because May Day, for me, was International Workers’ Day on 1 May. But as you probably know, the May Day they were talking about was the festival and going up the Magdalen Tower and all of that, right? And it’s one massive boozing party as far as I could see, right? But then, for, like, three days, I was like-, so then, like, I say, ‘Hey, I don’t know. Some people, like, really-, I thought they were all quite conservative. They’re all getting excited about May Day. So, where’s this Workers’ Day rally?’ And I tell you, the people I’m saying it to, you cannot believe how they were laughing at me. They were just, like-, as we’d say in South Africa, ‘They were kacking themselves with laughter’, right? Like, really, really, they were finding it funny. And then they said, ‘No, no, no, don’t get excited. This is nothing to do with International Workers’ Day.’ But I made some really good friends there. I learned a lot. Actually, I learned a lot about my own country, because we had so much censorship here.

So, bear in mind that my Scholarship only started six months later. So, I had six months. So, I was volunteering with Christian Aid, Oxfam, and so on. And at Christian Aid, I did a thing where I helped them write some, sort of, outlines for various documentaries, so that people could understand what the documentaries-, so, I had this job where I would go in and just watch South African documentaries. I would sometimes be at the office at, like, 6.30 in the morning, because I wanted to watch more. And you can imagine how emotional it was, because every now and then I would see somebody who I knew, who had been killed, you know, pop up, even just, sometimes, as an image in a rally or something. And then of course, I spent a lot of my time doing stuff around mobilising support for the anti-apartheid struggle And then, I also had a real break, in a sense, because I couldn’t come home to do research on my thesis, but then somebody told me that Yale University had an amazing archive of South African resistance materials and the librarian there-, I think his name was Moore Crossey. My god, if that is right, it tells you how amazing my memory is for things I don’t need to remember. So, anyway, he had, like, 20 South African students that he had on retainers and every month, they’d collect all the pamphlets coming out. So, I then go to Yale in ’88, basically. So, the first year I’m at Oxford, second year I’m at Yale, and then, you know-, And the library was amazing, in Yale. But the Oxford experience was also about contributing. We set up an organisation called ‘Rhodes Scholars Against Apartheid’. And we set up the Bram Fischer Memorial Lecture, which was an interesting thing, but it’s no longer called that, because after the decision was made-, so, there was a conversation about-, you know, conventionally, people said we should have a memorial lecture. So, then, they said, ‘Who should we name it after?’. And then I said, ‘Maybe you should name it after a very prominent Rhodes Scholar (Abram ‘Bram’ Fischer (Orange Free State & New College 1931)) that represented Mandela in his trial, and so on. And he is the only Rhodes Scholar from South Africa who suffered the kind of repression that he did’, because he ended up dying with cancer and, you know, they had to release him from prison, and so on. And Bram Fischer could have become the Prime Minister of South Africa if he’d stayed within apartheid, but he broke away from it, and so on. So, I proposed it should be the Bram Fischer Memorial Lecture, and I said, you know, ‘He was a white South African. He was an activist Rhodes Scholar. He represented Mandela.’ Everybody loved it, and then they voted it should be the Bram Fischer Memorial Lecture. And then they went and researched it and they discovered that Bram Fischer was also a communist, and then a lot of the American students then said, ‘Ah, we weren’t told he was a communist’, blah, blah, blah, and then I knew that at some point, they would change it. Because American Rhodes Scholars are in the majority, so they were able to-, that was only after we left, that they were able to change it, some years later. And then, we did cool things when I was at Oxford. The Oxford Rhodes Scholars Against Apartheid and the Oxford branch of the anti-apartheid movement organised a fast – like, a hunger strike – to raise money to support the Solomon Mahlangu Freedom College, which was an ANC-run school in Mazimbu, Tanzania. So, I did my first hunger strike then. Seven days, with water, and I eat a lot, so it was very hard. But it was, like, a really good experience. I figured out things about myself as well as the people that were there, and we raised a lot of money to support the educational technology needs of the school in Tanzania. And while I was at Oxford, I was always being invited to speak at meetings about what was happening, quite often travelling outside of Oxford. And I’ve been to places in the UK I can guarantee you’ve not been to – Darlington, for example. You look-, do you know where Darlington is?

SC: No. Well, I am British, but not born in Britain.

KN: No, no, just to say, like-, mainly, I used to do it for Oxfam. They couldn’t pay me, but at least, it was, like, helping with-, if I went for four days to the north of England, they would put me on a train in London, an overnight sleeper, which for me was, like, luxury. An overnight sleeper, and I’d get there, and then-, from a learning point of view, it was amazing, right? I remember, once, Oxfam and this campaign called ‘Hungry for Change’, and they had all these small, local groups, and it was one hour from Leeds, like, a rural area, and I go there and, you know, these were the supporters of Oxfam, but you would find, for me, such high levels of racism. Like, for example, this one woman said, ‘You know, my sister lives in Kenya, and she pays the boy and the girl that work for her 50 pence a day. But they are so grateful’. You know. And then, like, I’m thinking, ‘You’re my ally and I’ve come here to work with you about winning over other people, and I’ve spent more of my time talking about, “Well, okay, that is exploitative to the local people”’, and so on.

So, the main thing that Oxford taught me, the main thing, which I’m very grateful for, is that, before I got to Oxford, most of the people that I engaged with on a day-to-day basis were people who had the same values, views and perspectives like my own. I was rarely speaking to people who were-, unless we were going out door-knocking or whatever. But in terms of day-to-day interactions. But at Oxford, even from the South Africans that were there, who were predominantly white South Africans-, we might have all – not all, but most of us would – be roughly anti-apartheid, but there are gradations of your antagonism to apartheid, let’s say. So, what Oxford taught me is to learn the skill of engaging with people who have different views from you. And that is the skill that allowed me to play the roles that I played globally, whether as head of Greenpeace, head of Amnesty, the head of the CIVICUS world alliance for citizen participation, or any number of UN global panels that I’ve participated in. You know, like, when I was on the eminent persons’ panel on UN civil society relations in the 2003/4 period, most of the people there had vastly different views than mine, but I was able to deal with it, and I always thank my Oxford experience for that. If I didn’t have those three years of being able-, but the way I used to say it was, ‘Getting the skills to deal with bullshit’, right? It’s, like, skills to-, because also, the one thing about the Rhodes Scholar Community that I’ve always found difficult is the sense of, like, ‘We are so great and we are so brilliant and the world should be lucky to have us’ attitude. I’m not saying that everybody has that. I’m not saying everybody has that, but it’s far too dominant. It was far too dominant for me.

Because for me, today, as I sit and talk to you, I’m happy to tell you that my life has been a failure, right? For everything that I’ve struggled and fought for, those agendas are not moving forward, whether it’s on gender equity, whether it’s on addressing poverty, whether it’s on addressing climate change, we are losing right now, on all those fronts. And ironically, the countries that were supposedly on the right side of the issues, like the UK and US, are today the most backward countries in the world. The US in terms of going after women’s rights, abortion rights, xenophobia, and so on. And to see-, you know, when Boris Johnson got elected in the UK, I went back, and there was a quotation that he had just said when he was the editor of the Spectator, or one of those things he was editing, where he said, ‘The only thing for Africa that will be right is, we should go back to Africa, and this time, we shouldn’t apologise like we did before.’ You know, this guy is a racist to the core and for us, you know, to see that happen-, I mean, listen, one of the things we used to say in South Africa, between the Afrikaners and the English, many people used to say, ‘Give us an Afrikaner any time, because we know they stand. They’re honest, they will say what their views are.’ However the offence of it is, too, they’re going to say, ‘I’m racist’, or whatever. On the other hand, the English tend to be more wishy-washy. They played it both ways. You know, they would say they’re against apartheid, but they’ll say, ‘No, Mandela is a terrorist and must stay in prison for 27 years’, right? All of that.

So, being in Oxford also helped me understand the awesome and troubling power of British imperialism, even today, right? And I was able to smell it and experience it. And today, let’s be very clear, the role of the UK as a government and as a country, and the role of the US: history will judge they have been on the wrong side of history consistently. Today, many of the conflicts that we are dealing with in the world stem from those British colonial and imperialist crimes that were done over a long period of time. And Cecil John Rhodes is a central part of it, and we cannot run away from it. And so today, as I speak, as a Rhodes Scholar, I would be happy if we changed the name of the Scholarship. I have said that we should. I think it’s-, would we, for example, have a scholarship in the name of Hitler? What’s different for us? He did more harm to us than Hitler did at his time. We’d never accept a scholarship in the name of Hitler. Why do we accept a scholarship in the name-, and of course, it’s complicated, blah, blah, blah, and yes, the Rhodes Trust is trying to do things which I-, I co-chaired one of those working groups until my son died and I had to step aside, right? So, you know, there is immense power and privilege that comes from the Rhodes Scholarship if you’re going to go into business and investing and so on. Obviously, in my case, it never helped me, in terms of advantage. Because basically, for me to go and say, ‘I’m a Rhodes Scholar’, it would be an embarrassment in the communities that I’m part of, right? So, I never use the title of Rhodes Scholar, really. I must confess, I do use it in one case, very, is to deal the visa regimes that I have to deal with. So, if I’m applying for a visa – which in my global jobs, most countries, being on an African passport, you have to apply for a visa – I would use the fact that I’m a Rhodes Scholar, and that seems to help, especially after Bill Clinton became a Rhodes Scholar. Most people in the US and all didn’t know much about Rhodes. Bill Clinton played a big role in making the Rhodes Scholarship much higher profile than it was in some circles. And so, I don’t think I use the Rhodes Scholar thing for anything. Or even my PhD title from Oxford. I use that only in visa applications. Of course, sometimes other people might refer to me as ‘Dr’ or ‘Professor’, or whatever, but I don’t actively use any of that, because I don’t think that matters, right? It shouldn’t matter. And also, don’t you think it’s embarrassing? You know, that all the money for the Rhodes Scholarship came from the exploitation of the peoples of Southern Africa and its wealth, and then you have the majority of the Scholarships being given to the United States, right? I mean, it just, you know-, and me, people say, ‘Oh, be realistic, that’s just history’, but I refuse to accept that just because something was unjust before and was unjust for a long time, therefore it can continue. If you take that logic, most women wouldn’t have the right to vote, for example, and many other things. So, a bit off-topic, I’m sure, but the experience of Oxford, for me, was about all of those things. And so, my gratitude was, for the work that I ended up doing, I got skills from Oxford of how to see the humanity and people who have vastly different views about the way the world is, and for me, that’s the most important skill I got out of Oxford, not content around my subject area, and so on.

HN: It would be great to ask a last couple of questions. So I wanted to ask, what motivates and inspires you?

KN: So, I’m currently motivated by the fact that humanity is so close to the cliff of despair. I mean, that we are in the cliff of despair and that we are so close to catastrophe on a scale that we cannot even imagine. So, basically, right now, our global political and business leadership are sleepwalking us into a crisis of epic proportions. We’ve known about it for a long time, in terms of climate and what its impact is, and so, I am motivated by my love and commitment to future generations and to understand that we don’t inherit the Earth, but we borrow it from future generations, right? And for us to live with responsibility means that we have to be able to hand it over, in generational terms, to Sarah’s generation in a way that they have a chance to be able to prosper and had what we had, and so on. So, my motivation is, things are drastically frightening and scary at the moment. But here’s my difficulty as an activist, right? So, I’ll give it to you in an anecdote. Like, I’m speaking at a meeting in the US some years ago, and I’m talking about how the forests are disappearing, how the oceans are rising, how inequality is rising. At the end of the speech, a very upset delegate put up her hand and said, ‘Dr Naidoo, have you heard of Martin Luther King?’ I said, ‘Yes. I’ve heard of him. He inspired me and many people in my country during our struggle for liberation.’ And then, she asked, ‘Do you know what his most famous speech was called? Thinking that it was a trick question, I answered very gently, ‘I have a dream’, and she shouted back, ‘Yes, it was “I have a dream”, but when you speak, you have a nightmare. You know, the forests are disappearing and’-, so, one of the challenges of leadership right now is, how can you speak truth to power? How can you not sanitise the fact that, basically, humanity is on a fundamentally suicidal trajectory right now, right? But how do you do it in a way that does not demotivate, immobilise, and so on?