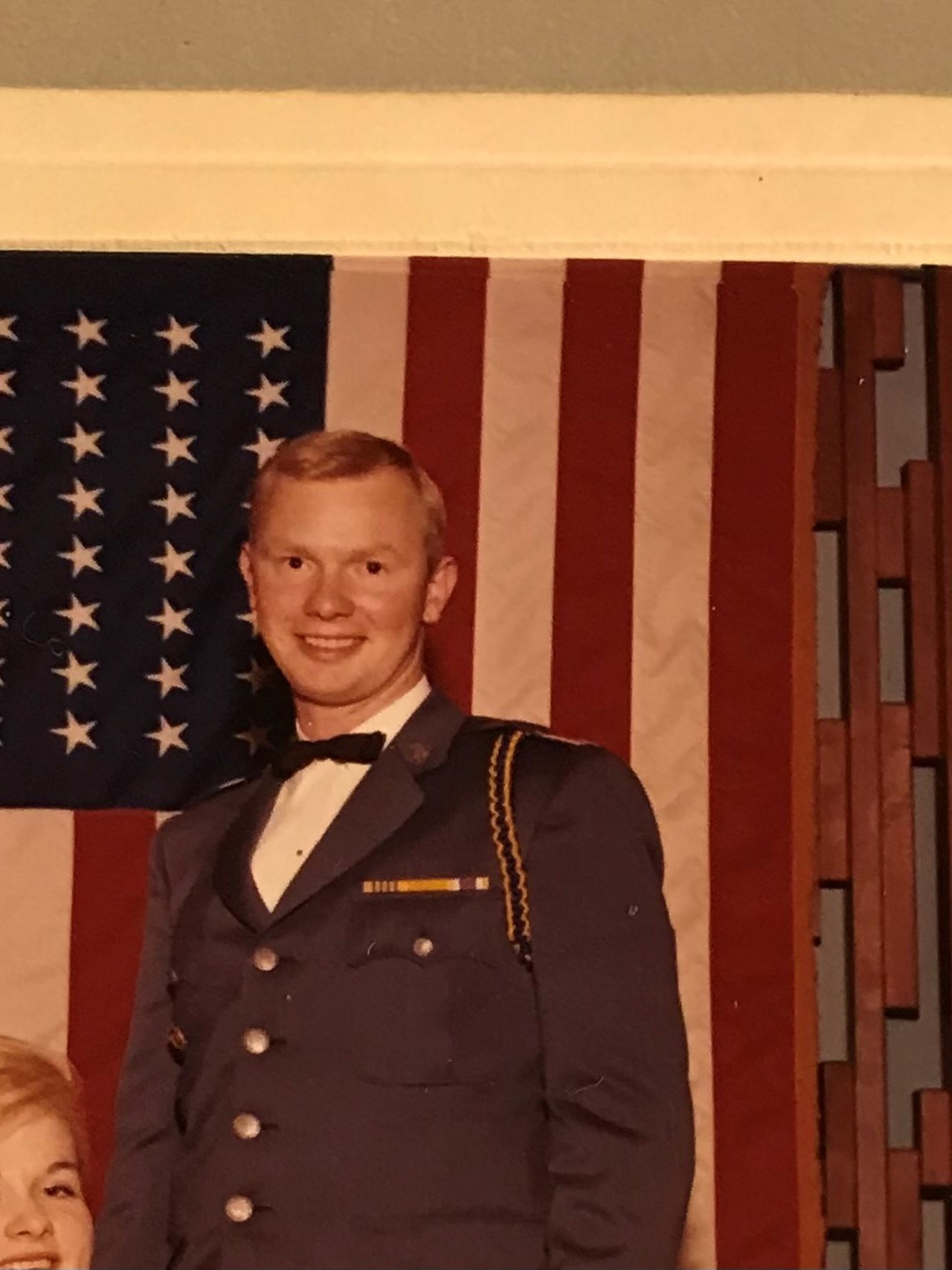

Born in 1943 in San Francisco, Kent Price studied at the University of Montana before going to Oxford to read for a second undergraduate degree in history. After a period serving in the Air Force, he went into banking, holding management positions across the world before then moving into CEO roles, assisting companies with restructuring. Price became founder and President of Parker Price Venture Capital, Inc. and is now a member of the board of directors of the University of Montana Foundation. He is a generous supporter of the Rhodes Trust and continues to offer mentorship to current Rhodes Scholars. This narrative is excerpted and edited from an interview with the Rhodes Trust on 20 September 2024.

Kent Price

Montana & Pembroke 1967

‘I went to eight schools in twelve years’

My dad was an officer in the Marine Corps. A week after he graduated from the University of Montana, we were at war, and he went to sea. He had met my mother in San Francisco, where I was conceived, and I didn’t see him again until I was two and a half. So, I grew up as a Marine Corps dependent, and we lived all over the world. I went to eight schools in twelve years.

We would move in the summers, and that meant lots of time before starting school. I would spend it devouring books and then, at school, I would immediately make friends. I was an athlete, so that helped. I also spent some of the summers with my grandparents in Montana, and I the outdoors life there, riding and hiking and swimming. I applied to the University of Montana because a high school guidance counsellor asked me where my father was from and told me that because he was from Montana, the university there would be sure to take me.

On applying for the Rhodes Scholarship

I had found school very easy, but when I got to college, I started to take things more seriously. I studied history and political science and got a very strong foundation. I joined a fraternity, but it was a bit like the Boy Scouts: I couldn’t be bothered with all the rigmarole. Because I had the highest grades in my class, though, I got a room up in the attic which was known as the monastery, and I just shut myself away and studied. This was the height of the Cold War, and I specialised in Russian history, because I had a fascination with the idea of ‘Know your enemy.’

Montana had an ROTC programme, and I chose to go into the Air Force. I ended up being the outstanding Air Force cadet. When I graduated, the Air Force had exceeded its legal limitation of officers, and they suggested I go on to graduate school. I did a master’s degree in Russian Studies at Montana, and during that time, I was approached by H.G. Merriam (Wyoming & Lincoln 1903), who had been in the first ever class of Rhodes Scholars. He and Burly Miller, the long-time retired dean of students told me about the Rhodes Scholarship application process. I thought, ‘No guts, no glory. Why not?’

The first time I applied, I actually didn’t get the Scholarship, but H.G. Merriam encouraged me to reapply the following year. By that time, I was pursuing a PhD at UCLA. I found the interviews fun, but when they read out the names of the successful applicants, I couldn’t believe I was on the list. Hearing my name called was one of the most memorable moments of my life, and it really was life-changing for me.

‘I couldn’t believe this little kid from Montana was in this magnificent place’

When I won the Scholarship, I asked the Air Force whether I could defer, my service. They said I couldn’t, but they allowed me to be a Scholar while on active duty. That meant I was lucky enough to have the Rhodes stipend while also receiving a salary. I spent a lot of time in the vacations travelling, all over Europe, and to the Soviet Union, and even made a trip to the South Pole.

For all that, I was a little overwhelmed when I first got to Oxford, and I was pretty depressed the first two months I was there, not least because it rained constantly. England at that time was fairly bleak, and there were parts of it that I did not like then and still do not like now, namely what I would call the upper-class twits. But my college experience was wonderful, and I couldn’t believe this little kid from Montana was in this magnificent place. I played rugby, I rowed, I played cricket. I had brilliant tutors in history, and I would say that Oxford is where I learned the beauty of the English language and where I really learned to write too.

That was a time when, after years of travelling around and not really making firm friends, friendships started to stick. Also, at UCLA, I had met an English girl, and when I got to Oxford, I called her and we met up in London. She went on to become my first wife. We were married after I graduated, and we have three children and ten grandchildren, so, that was what you might call a permanent souvenir of Oxford.

‘I took joy in building organisations’

After Oxford, I remained in active service in the Air Force. I had initially wanted to fly planes, but because I had a background in Russian studies, I went into signals intelligence, where we worked as part of the NSA. So, I learned all about computers and telecommunications, way before anybody cared about them. When I left the Air Force, I thought at first that perhaps I should go to law school. I applied, and I’d been accepted, but I realised before I started that it just wasn’t something I wanted to do.

I talked to a friend of mine about business, and he said, ‘Well, the best way to learn about business is to join a bank, because everything revolves around money.’ So, I wrote to what is now Citibank and asked if they were hiring, and they took me on and put me into international training because I spoke a couple of languages and had lived abroad. I was with Citibank for almost 15 years and in that time, I was in New York, Dublin, Belfast, Nigeria, Ivory Coast, Taiwan, Hong Kong and London. I was very successful, but when Citibank got a new chairman, he and I didn’t get along very well, so I decided to move on. A friend of mine worked as a kind of company doctor, going in and fixing ailing companies, and he took me on as a CEO for one of these companies, which started about 20 years of work in that field. I took joy in building organisations, and even if I didn’t always manage to turn a tugboat into an ocean liner, I was usually able to turn a tugboat into a yacht, at least!

When I was 55, I decided I should retire, but I quickly got bored. A friend asked if I would join him in his venture capital firm, and I was active in that work for around ten years. I enjoyed it, and I think there is an entrepreneurial spirit that runs in my family. My great grandfather had it, coming from Canada and setting up in business in Montana, and my eldest son now has it too, raising money through venture capital and investing in Montana.

Looking back across my life, I would say that the Rhodes Scholarship was the touchstone of everything that I’ve done since. Getting the Scholarship and buying in to Rhodes’ original notion of ‘The best men for the world’s fight’ made me feel like I had a mission. I wanted to get to the stage of life that I’m now at and be able to say, ‘The world is just a little bit different because you passed through it. It also gave me the confidence to aspire to do good things and to think, ‘Hey, I can do this.’ I’ve had successes and, of course, I’ve made mistakes, but on balance, I think I’ve touched a lot of people, directly or indirectly. I’ve set up scholarships at the University of Montana. I’ve tried to be a mentor to people and I’ve tried to set an example, because I think that those who have been fortunate enough to receive should then give back

‘Don’t be in a hurry’

To today’s Rhodes Scholars, I would say, don’t be in a hurry. Oxford should be a hiatus, where you get deeply into English culture. It isn’t the end, it’s the beginning. Enjoy your time in Oxford, take full advantage of what you’re doing, and remember that, in the best possible way, being a Rhodes Scholar doesn’t assure you of anything. It’s just gets you in the door.

One of my bosses once told me that your 20s and 30s are your quiet years. You take yourself seriously, but nobody else does yet. And so, what you want to do in those years is get as much experience as you can, because from experience comes wisdom. Then, when you get into your 40s and 50s and people start to take you seriously, you can reach into your back pocket and use your experiences to come up with wisdom.