Born in Livingstone, Zambia, Kenneth K. Mwenda studied at the University of Zambia and the Law Practice Institute (now the Zambia Institute of Legal Studies) before going to Oxford to read for the BCL (Bachelor of Civil Law). After a period as a lecturer at the University of Warwick, he earned his PhD and then moved to the US, taking up a position at the World Bank, where he has now worked for 27 years. Alongside his current role as the Manager and Executive Head of the World Bank Voice Secondment Program (VSP) at the World Bank, Mwenda continues to maintain an impressive academic profile. He is the author of over 30 scholarly books and over 100 peer-reviewed articles and is the recipient of numerous awards and honours, including two higher doctorates earned from Rhodes University in South Africa and the University of Hull in England as well as an Honorary Fellowship at Exeter College, Oxford. This narrative is excerpted and edited from an interview with the Rhodes Trust on 2 January 2025.

Kenneth Mwenda

Zambia & Exeter 1992

‘I grew up in a home where education was a priority’

I was born in Livingstone, Zambia, and spent my early childhood in that lovely tourist city before my family moved to the Copperbelt region of Zambia. Zambia is located in Southern Africa and is the neighbouring country to Zimbabwe, Mozambique and Botswana. We were a big family of eight children. My parents were both civil servants. My dad studied at the University of Toronto. My mother trained initially as a nurse and then switched careers to become a teacher. So, I grew up in a home where education was a priority.

I went to kindergarten and elementary school in Livingstone, and because my family are Catholic, I went mainly to Catholic schools until I progressed to high school. My family was always inclusive and respectful of other religions and Christian denominations, of course, but attending church on Sunday was non-negotiable. Also, discipline in the family was important for everyone. In 1976, we moved to the Copperbelt Province of Zambia where I went to an all-boys government secondary school, Luanshya Boys’ Secondary School. As a child, I enjoyed playing soccer on weekends. When I went to high school, I became a cadet and was also an altar boy at church.

On applying for the Rhodes Scholarship

At the time, there were only really two universities in Zambia, so getting in was intensely competitive. I had some great professors who were role models for me, including Dr Caleb M., Fundanga who went on to be Central Bank Governor of Zambia. University was a very dynamic academic environment, very vibrant. The scholars I encountered there were beacons of intellectual hope.

I was very industrious at university and having done my first year with a broad social science base, I decided it would be a good idea to take UK A levels alongside my degree work. I managed to pass, and then I went on to graduate in the top two of law school as well, winning a prize as the best student in jurisprudence. I studied for the bar at the Law Practice Institute, passing all my exams at the first attempt, which was quite rare. After that, I was hired by the University of Zambia as a Staff Development Fellow and Tutor, to be trained as an academic.

I wanted to go abroad to do further study, but I was told that the university did not have funding for that. Then, I met a friend who asked what I was up to, and he said, ‘There’s a scholarship that’s been advertised in the newspapers. Look it up.’ Well, that was the Rhodes Scholarship. I thought, ‘Let me give this a shot.’ When I showed up for my interview, the committee was perplexed about just how many extra qualifications I had. I explained to them that, ‘I had channelled much of my energy towards school.’ They asked me about whether I would really come back to Zambia and to academia. I pointed out to them that I could have been earning far much more money if I had gone into law practice but chose instead to stay in academia. To this day, I have never really left academia, and I continue to help universities in Africa, like I promised the committee when I was being interviewed for the Rhodes scholarship.

‘Every experience was a learning experience at Oxford’

I was lucky to get direct admission to the BCL at Oxford, although when I first heard the full name of the BCL degree I mistakenly thought it didn’t sound as high-level as a master’s degree simply because of the nomenclature associated with it. I later discovered that the Oxford BCL is actually the most rigorous and most prestigious taught masters degree program in law in the entire English-speaking world. In fact, it is extremely competitive to get admitted to the Oxford BCL. And the intensity of learning on the Oxford BCL, with one-on-one tutorials, remains unparalleled across the world. I studied night and day as an Oxford BCL student. There was no resting. It paid out well and I passed with top grades. For the third year of my Rhodes scholarship, I wanted to get an MBA, but Oxford wasn’t offering one at the time. So, I was able to go up to the University of Hull and study management and leadership there.

Every experience was a learning experience at Oxford. I have very fond memories of good friendships and conversations alongside my studies, but it was certainly a big cultural shift. What kept me going were the letters my father would send me. He understood from his own time at university in Canada what it felt like to be a long way from home and family. I’ve maintained ties with Oxford over the years too, bringing my mum and dad to see the city and now, my wife and son as well. When my wife and I had our honeymoon in Europe, we even stopped over at Exeter College!

‘I’ve led dual parallel careers’

After Oxford, I decided to stay in the UK and explore the prospects for academic work. A lot of my friends from Zambia said, ‘You’re too ambitious. You cannot teach at a British university,’ but I applied to Warwick, and I was basically the first Zambian lawyer to teach at a British university with a full lectureship. I was only 26 years old, but I’ve always believed in myself. I think you just must do things on your own merit. At Warwick, I also went on to develop my Oxford master’s work into a PhD. After that, I decided that I should move to the US and try out the academic environment there. I won a competitive full scholarship at Yale University Law School to pursue further postgraduate legal studies with a view of converting to American law. In the meantime, I also pushed in an application to the Young Professionals Program at the World Bank and was accepted. I was lucky enough to have a really good mentor who spoke to me about what I wanted, which was to work in the US as soon as possible. So, I chose the World Bank, and I was the first Zambian to be in that programme.

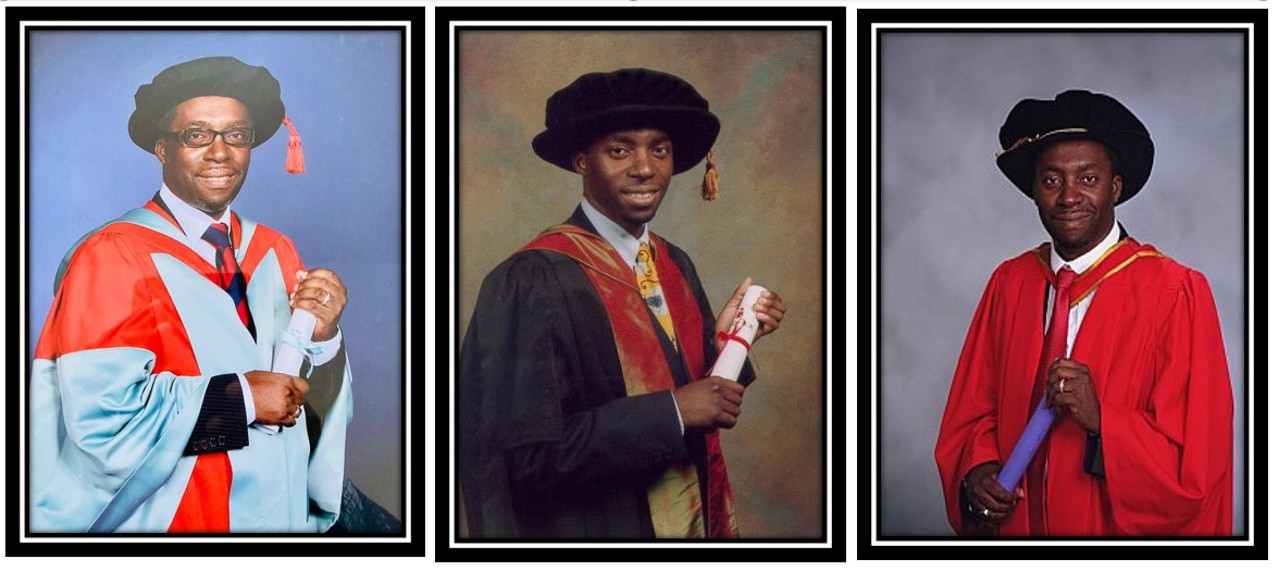

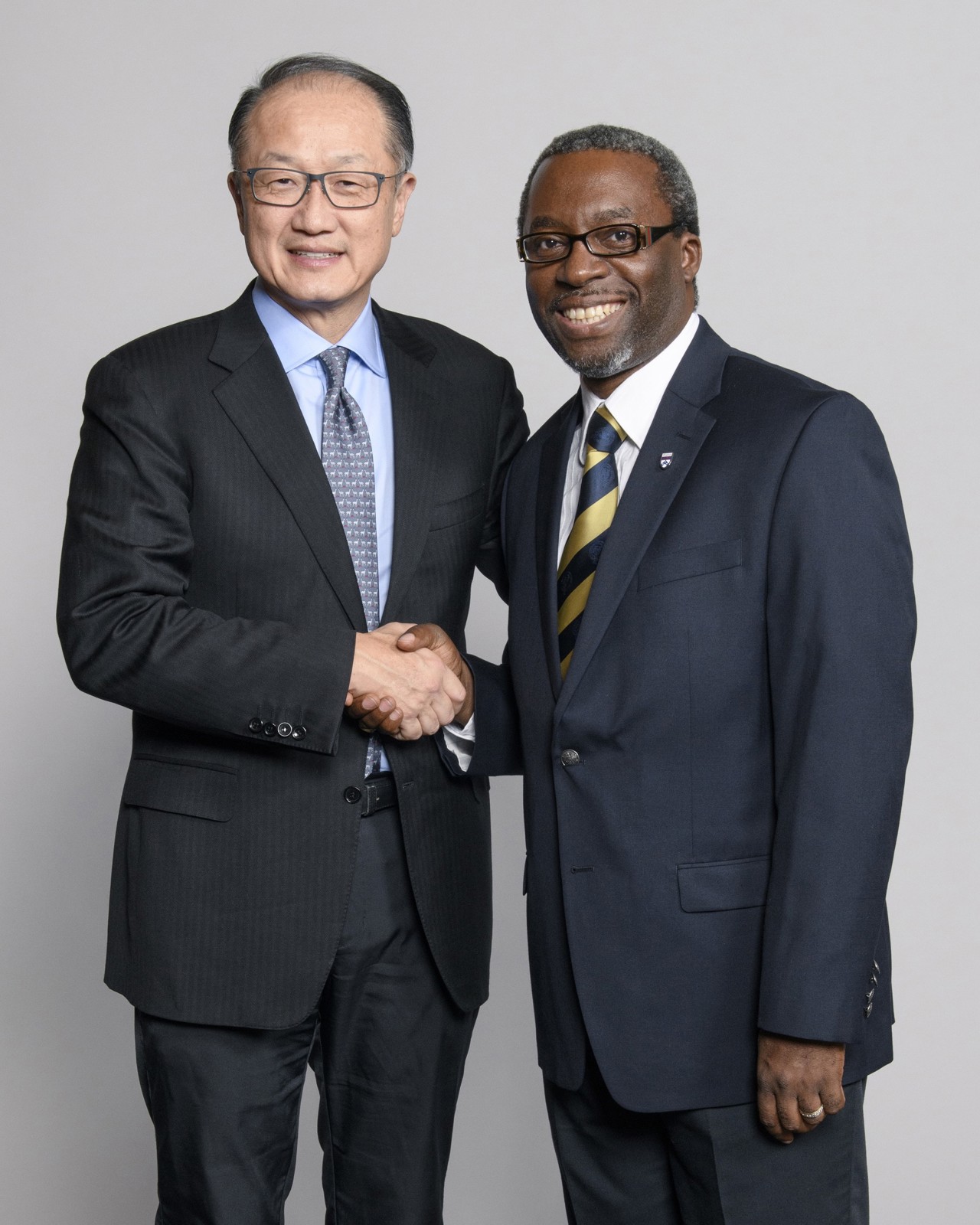

I’ve led dual parallel careers, as an academic and a development practitioner. I’ve worked on almost all regions of the world during my career at the World Bank, spending time in operations and in the legal department, including as Senior Counsel. My current role is leading the World Bank Group Voice Secondment Program which was set up to build capacity in eligible World Bank client countries. Throughout much of the time I’ve been at the World Bank, I’ve continued teaching at leading universities and publishing in high impact peer-reviewed academic journals as well as writing scholarly books. I’ve never dropped that scholarly side of me. In 2008, I was awarded my first higher doctorate. It was a Higher Doctorate in law from Rhodes University. I had to put together a portfolio of large volumes of my published work and send it to Rhodes University for examination. It was the first time that Rhodes University had conferred a higher doctorate in law. When I went to South Africa for that ceremony, there were so many emotions going on. I was thinking a lot about my dad and all the guidance he would often give me. Six years later, in 2014, I was awarded my second Higher Doctorate. It was a Higher Doctorate in economic sciences from the University of Hull. Again, I went through the same rigorous process of submitting for examination a voluminous portfolio of my published scholarly work which had been published after earning my first Higher Doctorate.

I still work with colleagues in the University of Zambia where I’m currently supervising two PhDs. I’ve also adopted an institution that I support through philanthropy, the Dagama School for children with different abilities in Luanshya, Zambia, which is run by Franciscan nuns. And the honours keep coming in. In 2019, I went to Zambia with my wife and son to receive the Presidential Insignia of Meritorious Achievement. In 2023, I was made an Honorary Fellow of Exeter College. That was very moving too, and I’m so grateful and humbled for the amazing welcome and treatment that I received.

Through all of this, my approach has always been that work-life balance is very important. So, what I would do, for example, is that where there’s work to be done, I would travel there. But as soon as I got back from work-related travel overseas, I would give my family an opportunity to travel with me on vacation.

‘You’ve got to love what you’re doing’

In my humble view, you must develop careers which make you fungible and not easily substitutable. Also, you should always live for the present while anticipating the future, as you look at trends and scenarios of what the job market might look like tomorrow.

People say that in life you can either do well or do good, but I think you can do both. Whatever opportunity you get, always think of how resourceful you can be and what result you can give back. When I teach in South Africa, for example, I’m not paid. I volunteer my time. I also mentor other lawyers, including judges, and I mentor Rhodes Scholars as well. All of this must come from the heart. You’ve got to love what you’re doing. In the 27 years I’ve been with the World Bank, I’ve seen what it means to give back to society, and those are the values that drive me.