Born in the Kambu district of Kenya, Ken Kamoche studied at the University of Nairobi before going to Oxford to read for a MPhil and DPhil in management. He began his academic career as a lecturer at the University of Birmingham and later moved to become Associate Professor at the City University of Hong Kong. Returning to the UK, Kamoche was appointed Professor of Management in Nottingham Trent University. He is currently Professor of Management at the University of Nottingham where he is also Director of the Africa Research Group. Alongside his academic work, Kamoche is also a writer of fiction and has published a collection of short stories – A Fragile Hope, shortlisted for the Commonwealth Best First Book Award – and the novels Black Ghosts and A Clan of Warriors. This narrative is excerpted from an interview with the Rhodes Trust on 21 February 2025.

Ken Kamoche

Kenya & St Catherine's 1988

'We grew up listening to and telling stories’

My ancestors were simple folk who worked the land in Central Kenya. My maternal grandfather was conscripted to fight for the British in the First World War, so he is one of the forgotten African hero soldiers of the British Empire, fighting for a war that really had nothing to do with him. It was just a job. It troubles many of us from Africa who had family in those wars when we mark something like Remembrance Day in the UK, because the history of the fighters in these ancillary forces is not taught with any honesty or seriousness in schools.

I was born and raised in a little village and although I haven’t lived there for a long time, every time I go back to see family and friends, I’m reminded of just how simple life was there. Like every African boy, I dreamed of football glory. There was no TV so, you would listen to the matches on the radio and then attempt to replicate what you heard on the pitch. We made our own footballs and our own toy racing cars as well, and because we lived on the edge of a forest, we would go out exploring a lot.

I started off at nursery school, but after a year, when I signed my name to a drawing, the teacher decided that if I could write, then I should go on to primary school. I ended up going to three primary schools, and one of my main recollections is around storytelling. We grew up listening to and telling stories and I remember making up a story to tell to the class that was very modern, not based on the old folk tales, and it got thunderous applause. I really started to thrive in the last of my primary schools and from there, I went on to the Nairobi School, which was great. I got to study the sciences and I also sharpened my interest in literature and fine art. I was involved in drama, and that was the time I began seriously writing plays and poetry and even my first novel, although it never saw the light of day.

On applying for the Rhodes Scholarship

I chose to study commerce and accounting at university, and in the vacations I was fortunate to get a job with an audit firm where I learned to marry the theory to the practice. That was fascinating. I filled up my time at university with learning the piano, and also Italian and Arabic, at least until the last year, when I had to concentrate on my accountancy studies. And just before my finals, I got the chance to spend three months working in Poland as an intern, which was one of the most rewarding experiences of my life.

I owe the whole Rhodes thing to my dad, who had saved a newspaper cutting about the Scholarship and said, ‘This might be interesting for you.’ I got back from Poland to find that I’d made the shortlist, and I threw myself into preparing for my interview like my life depended on it. It became a dream, an obsession. So, when they told me I’d won it, I literally cried. I couldn’t believe it.

‘Oxford was about burning the candle at both ends’

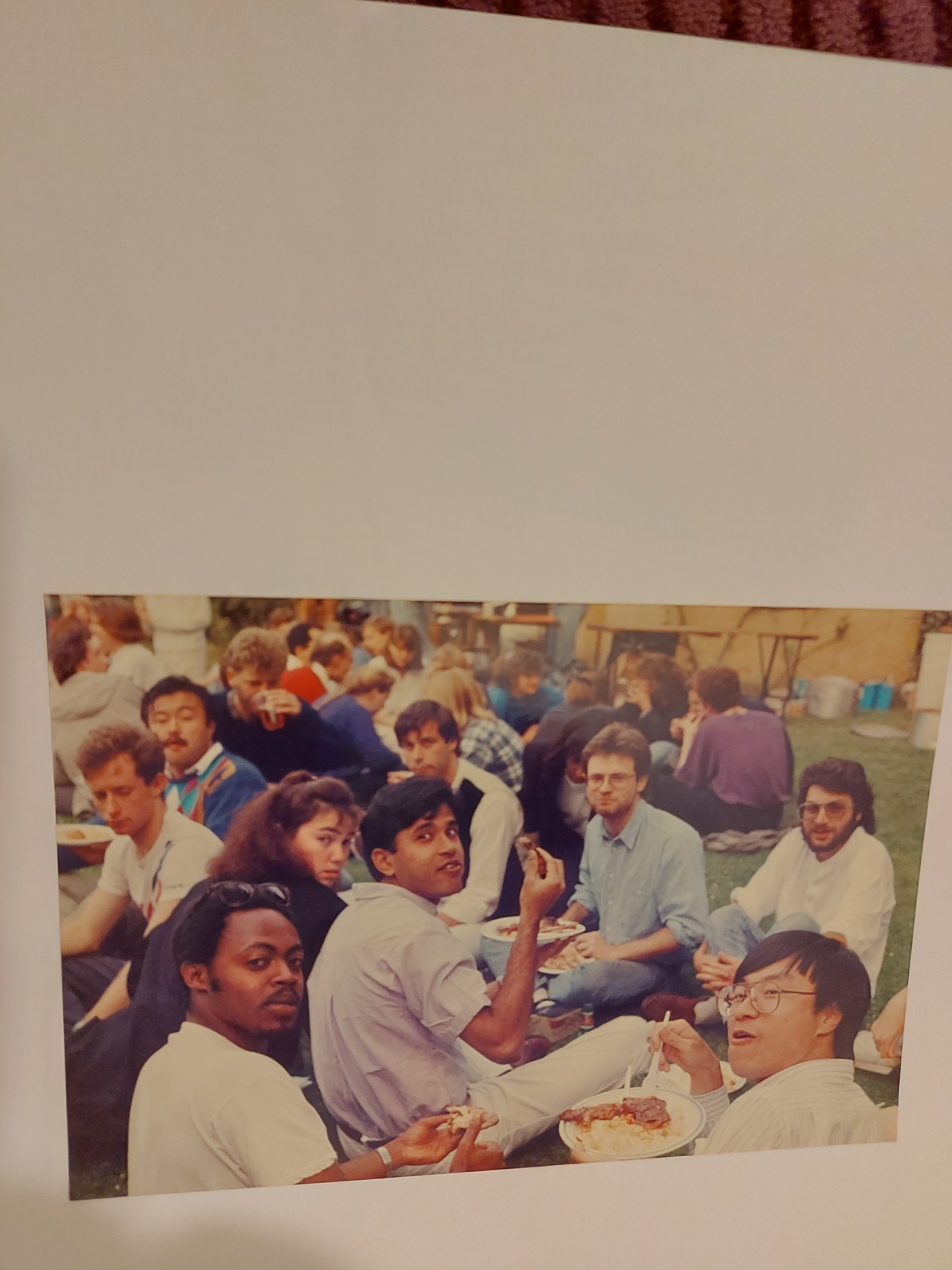

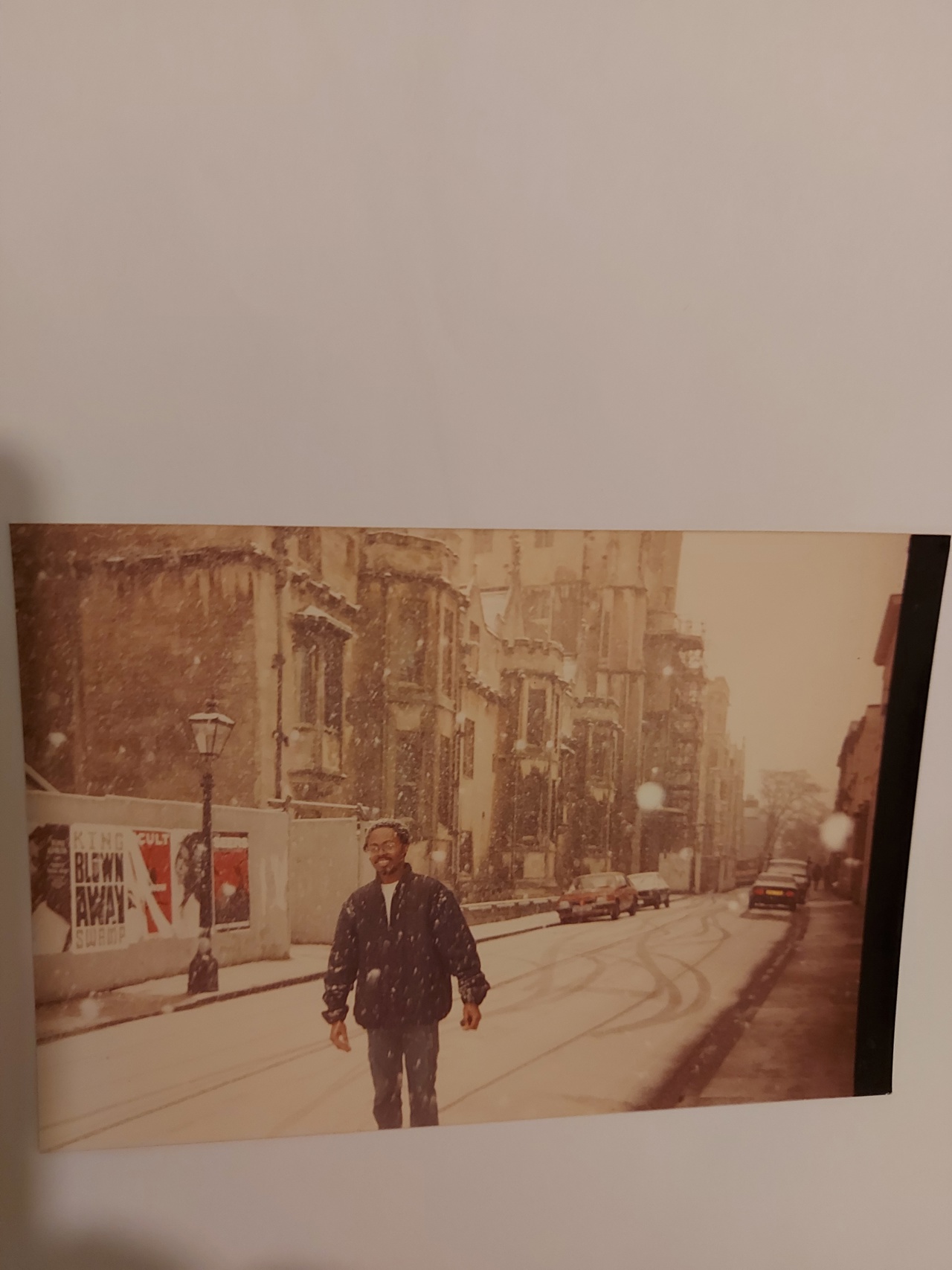

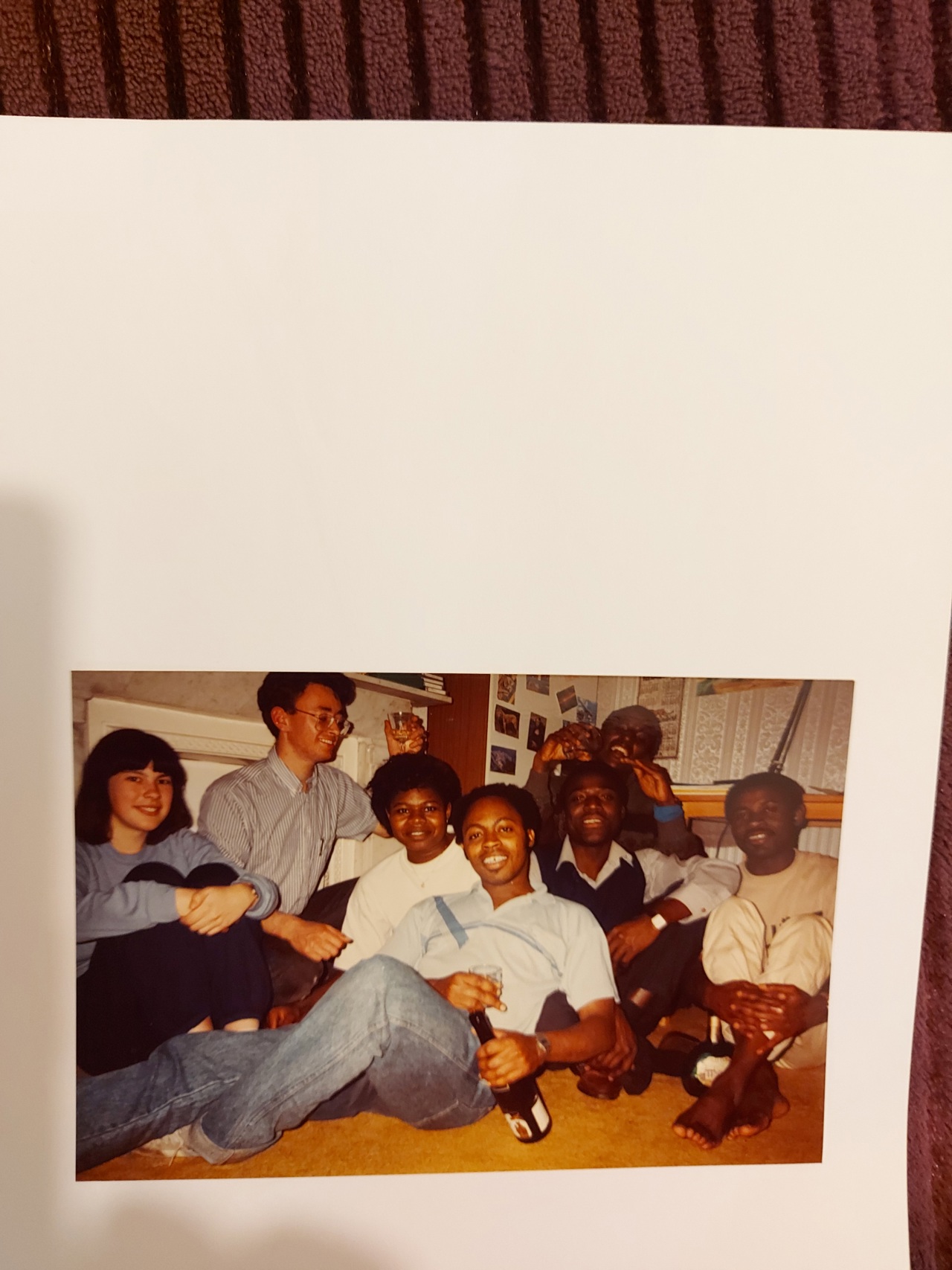

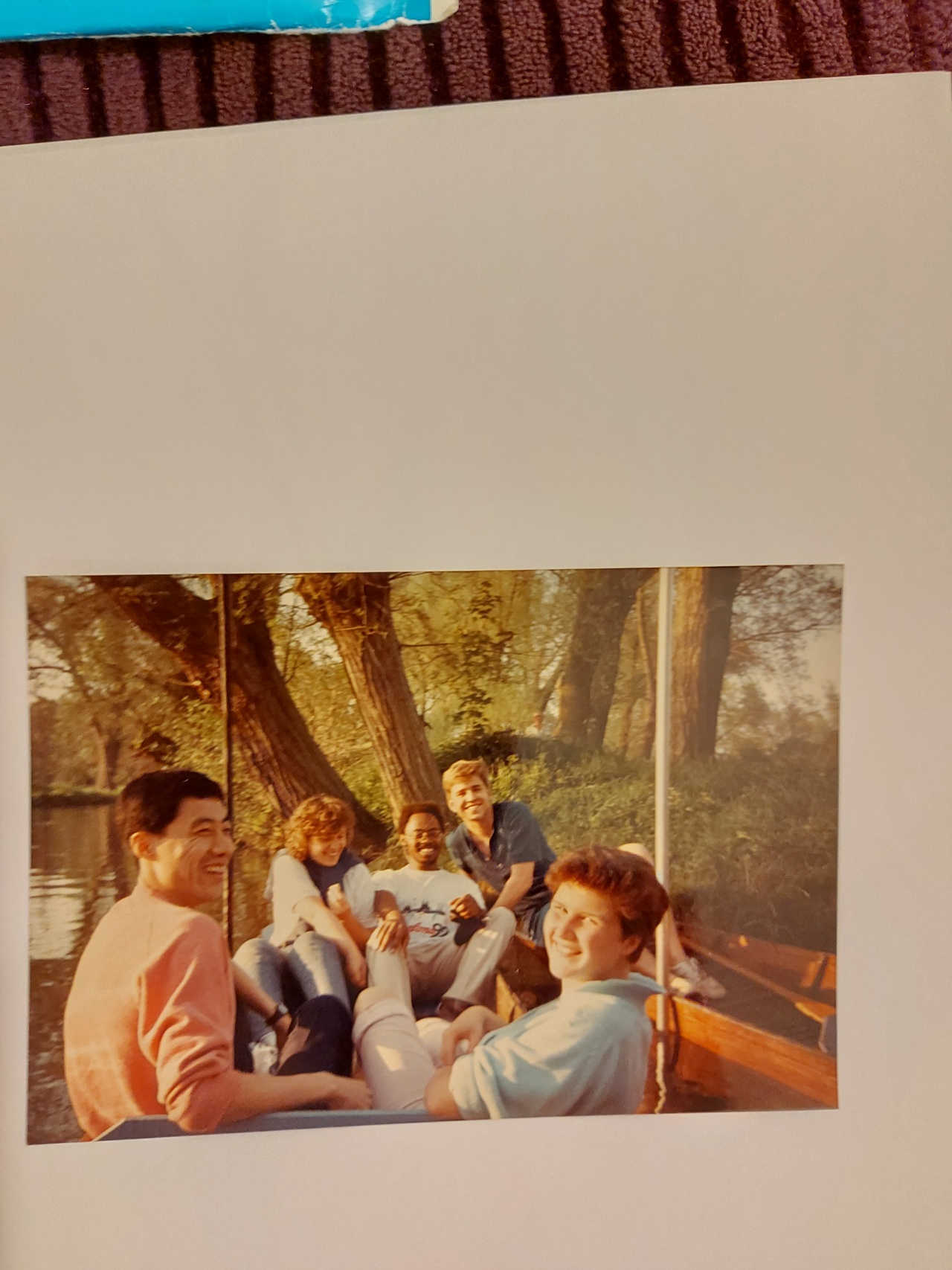

Oxford was about burning the candle at both ends, expanding my general education but also re-engaging with sports. I absolutely loved being there with all these smart people and with so many exciting things going on. I was very much involved in leadership and in debates in the African Society and the Kenyan Society. And, of course, Oxford had this whole history of writers like C.S. Lewis and so forth. Being part of that history was very rewarding and very moving in a way. I also enjoyed finding acceptance in those spaces that students didn’t venture into, getting to meet local people who lived and grew up in the city.

I have to say that it wasn’t always smooth sailing being identified as a Rhodes Scholar. There were those who thought you were some kind of royalty, enjoying undeserved privileges. But I think once they got to know you they realised that that kind of perception couldn’t have been further from the truth. And it was a bit rich, being told by other Oxford students how privileged we Rhodes Scholars were when at that time, it was very much white public school people with middle-class accents. At that time, there was starting to be quite a lot of pushback against historical injustices and I set about trying to educate myself about Cecil Rhodes. I think that helped me to bolster my own voice to work towards a better Africa.

‘I knew I wanted to do something that would involve knowledge creation’

There are two sides to my career and life: the fiction, and the academic. My academic career came about because I started to get fascinated in the late 1980s by how everyone was talking about Japanese business successes and by the blend of culture and technological innovation which defined Japanese excellence. It was while I was in Japan gathering data for my MPhil that I realised research was what I really wanted to do. I can’t say I had a very strategic plan in terms of my career, but I knew I wanted to do something that would involve knowledge creation and embracing different cultures and travel and I wanted to make a difference to business practice and policy.

In addition to my full-time academic positions, I’ve enjoyed being associated with numerous universities around the world, leading seminars and global research teams and mentoring and inspiring other researchers. For the last 15 years, I have been leading the Africa Research Group, which is a global community of scholars who have an interest in Africa. One of our key concerns today, for example, is seeking to understand how African economies can more meaningfully engage with China. I don’t believe that African people are benefitting as much as they might, and that’s partly because their leadership has not put its best foot forward. Working on these kinds of areas is so rewarding and I have enjoyed every minute of it.

Writing fiction is something I always wanted to do, from around the age of eight when I discovered storybooks, and it took me a long time to get there, but I was always writing and also drawing as well. My published work begins with my collection of short stories, Fragile Hope, which I wrote while I was living and working in Hong Kong. My fiction writing really took off there, partly because I was able to engage with a writing community which met once a month to critique each other’s work. One of my stories, ‘Random Check,’ came about after I saw that, coming back to Hong Kong from travelling, there was a very high risk of being pulled aside. I quickly discovered that it was only black people who were being pulled aside, but when I asked about that, I was told, ‘No, no, no, it is only your imagination. This is a random check.’ That grew into my novel Black Ghosts, which allowed me to explore the China-Africa nexus. My second novel, A Clan of Warriors, is set in the time of the terrible dictatorship we had in Kenya when state-led corruption became a way of life, and I tried to explore what that meant for ordinary Kenyans. I’ve just completed a third novel, set in colonial Kenya, which is with my publisher now.

‘Come to Oxford with an open mind’

If I could go back to university and do it all again, I think I would want to study literature, which is my real passion. But I have no regrets. I enjoy what I do, and I think that studying management opened up so many opportunities. There are certainly some very interesting overlaps between my academic work and my fiction.

I would definitely urge today’s Rhodes Scholars to come to Oxford with an open mind. As a Rhodes Scholar, so much of your old life will be stretched and challenged. I would also say, never take yourself too seriously. It’s important to remember that the privileges and the generous funding come with a responsibility that will follow you around like a shadow throughout your career. You’ve been blessed to be at Oxford, so make the best of the situation and give what you can.