Born in Melbourne, Australia, Kathryn Brown studied at the University of Adelaide before going to Oxford to read for a DPhil in nineteenth-century French literature. After Oxford, she completed a law conversion course and worked as a lawyer for 14 years before reading for a second doctorate in art history and taking up an academic career. Brown’s published works include Women Readers in French Painting 1870–1890: A Space for the Imagination, Matisse’s Poets: Critical Performance in the Artist’s Book, and Dialogues with Degas: Influence and Antagonism in Contemporary Art and she is now Reader in Art Histories, Markets and Digital Heritage at Loughborough University. This narrative is excerpted from an interview with the Rhodes Trust on 8 April 2025.

Kathryn Brown

South Australia & Balliol 1988

‘I have to give a shout out to my parents’

I was born in Melbourne, but I grew up in Adelaide. My father’s half of the family are from Australia and my mother’s are British. My mother and her sister had come to Australia from Britain in their early 20s and that always struck me as something incredibly adventurous to do. They were so intrepid. I think my combined heritage gave me a particular perspective, because Britain was a place I had never visited, but one that captured my imagination. I come from a great family of storytellers and Britain was so often part of those stories. It was always lurking in the background, and I think that inspired me to come to Europe and explore Britain. In a way, I was doing what my mother and aunt did, but in reverse.

I have always loved books, not only for their content but also for their object qualities. As a child, I could often be found in a bookstore, just wandering around. I think that interest in the materiality of books is what’s inspired me much more recently in my academic career to examine books as artworks. Coupled with that interest that started in childhood was, and still is, sport and athletics. I must have been ten or eleven when I started as a sprinter, and running is still part of my life. I was really fortunate that when I was about 15, I joined an athletics club. It was very much dominated by girls and young women, a kind of proto-feminist environment, and that solidarity was very supportive. The other thing that was part of my life was music, and that has also stayed with me. I play the piano and my school very much fostered music. When my parents took me to Europe, I dragged them round Beethoven’s houses and places like that.

I went to Seymour College in Adelaide and that got me off to a fantastic start. We had small classes, so I was very lucky. The emphasis on the sciences was very strong. But I’m a champion of the humanities and I was doing modern languages, with incredibly gifted teachers in French and German literature. It was a very free time, and I have to give a shout out to my parents who indulged me and let me go on the imaginative and intellectual journeys I wanted to. I was never pushed down any particular path.

On applying for the Rhodes Scholarship

I went to the University of Adelaide and carried on with modern languages. In some respects, it just deepened what I was already doing. For me, learning French and German was about opening up a whole other world, learning another history and culture through those languages. I had two great books, the Penguin Book of German Verse, with a wonderfully moody Caspar David Friedrich painting on the cover, and the Penguin Book of French Verse whose cover was something flouncy by Fragonard. The poetry in them fired my imagination and frankly, it still does. Alongside my academic work, I kept up with my running and even briefly harboured ambitions to an actor, although I soon realised that wasn’t really me!

The Rhodes Scholarship was always something in the background. Of course, when I was growing up, women weren’t eligible. It was something I’d heard about that famous people or politicians had been awarded. I knew it was an extraordinary opportunity because, with no disrespect to Adelaide, I wanted to go somewhere else and explore other worlds. One day, someone said, ‘You don’t think you should have a go at the Rhodes, do you?’ and I thought, ‘Well, okay, why not?’

‘I was so lucky'

Oxford was my first extended period away from home, although I’d spent a semester studying in Germany when I was an undergraduate. On the one hand, going to Oxford was exciting and the opportunity I’d really, really wanted. On the other, it was a jolt suddenly to be on the other side of the world. I think I was lucky to be at Balliol for my PhD because it had a really strong international community. We were all in it together and the group was diverse enough to make you feel, ‘I can find some kind of place here.’ Although I do have to say that the 1980s had been a really difficult decade for Britain, so I was very aware that in the case of some of the people I was meeting, their sociopolitical reality had nothing to do with mine.

My daily life working on my PhD was great. I was so lucky with my thesis supervisor, Malcolm Bowie. He’d written about Mallarmé and Proust and I was writing about Baudelaire, so he was very much the person to have these conversations with and he was always so generous. He was the kind of person who was able to look at something you’d done and see the potential in it. So, combining that wonderful working environment with meeting new people who made the time meaningful was extraordinary. I should also say I met my husband Alan at Oxford, where he was studying philosophy, so that was also pretty good!

‘It was a wild thing to do, but it was great’

When I finished my PhD, it was, ‘Well, what next?’ All I’d known was academia. But then I saw a notice about a one-year law conversion course at Oxford Brookes, or Oxford Poly as it was then, and I thought that sounded really interesting. Some of the major law firms were offering to pay for that professional training and, a bit like my decision to apply for the Rhodes, I thought, ‘Why not?’ Sure enough, I got an offer from Slaughter and May and ended up going and doing law, which was as far from my world of poetry and music as possible. It felt like something much tougher, a new way of thinking and a new way of analysing.

I worked in the City and at a US law firm for about 14 years and it transformed the way I thought and the way I solved problems. I think it improved the way I wrote too. I confess though that in the latter years I started thinking about studying art and literature again, so I started another PhD, this time in the history of art. When I’d finished that, Alan and I thought, ‘Why not do something different?’ I got a postdoc at the University of British Columbia in Canada, so we just sold our apartment and went there. It was a wild thing to do, but it was great, and it opened up a whole range of new opportunities.

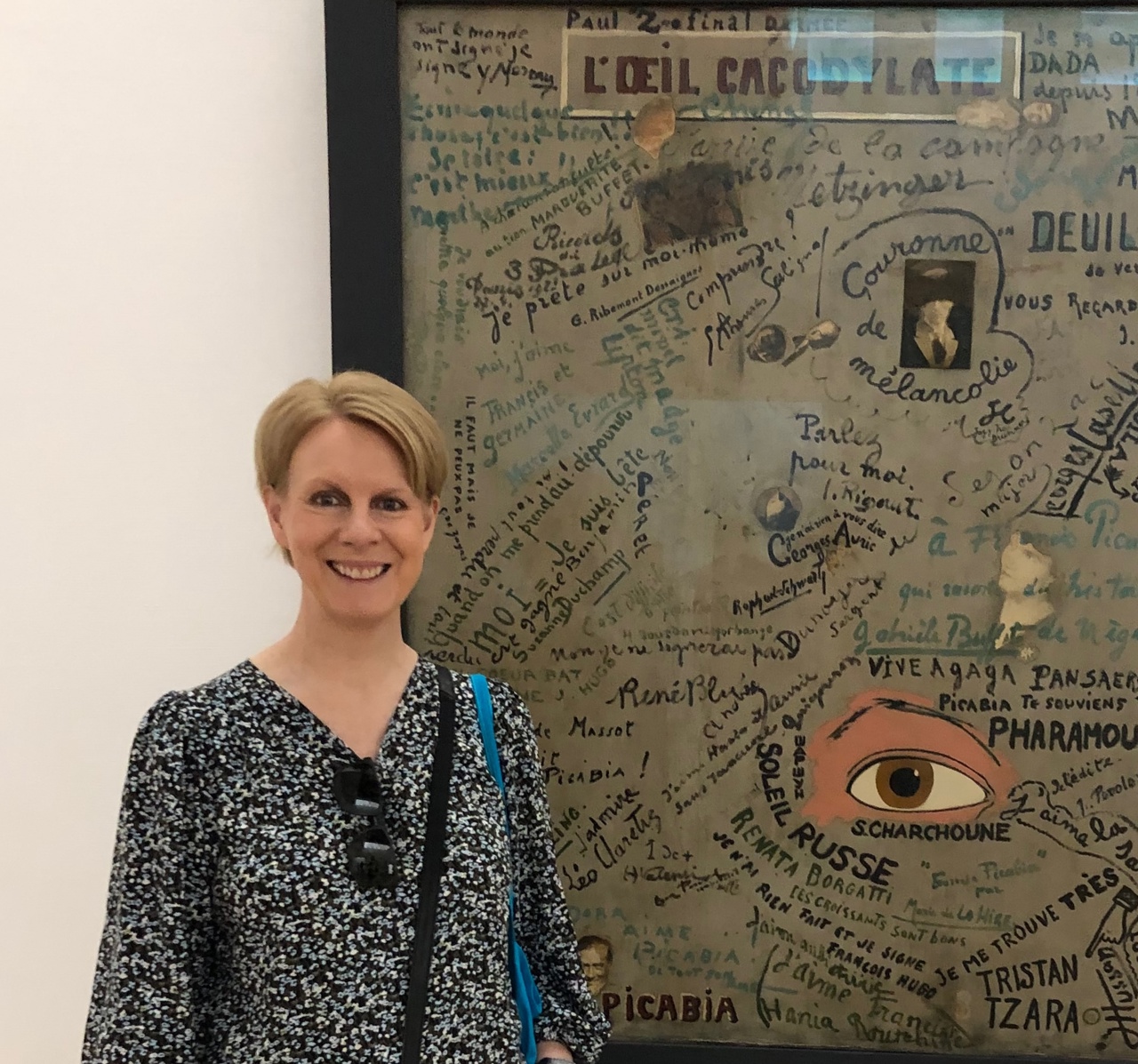

The first book I published was about women readers in nineteenth-century art, because I was interested in histories of female literacy, female solidarity, and how women were depicted in French painting. I still do a lot of work in that core art history area, but I don’t think you can really think about art unless you think about how it circulates. So, my thinking is very much wrapped in the economics of art, and I also focus on digital heritage. We’ve got museums and artists using computers and AI, and it’s fascinating to think about what these things are doing to our experience of art. I’ve taught in many different universities across the world, and I count myself very lucky to have been able to do that. Now, I’m based at the University of Loughborough and I’m very happy there. I don’t know what will happen next, but I like the UK and I think it’s a great place to be.

‘Keep getting up to the plate’

I think one of the good things about the Rhodes Scholarship is that there isn’t any ‘One size fits all.’ There isn’t one kind of Rhodes Scholar. So, to anyone thinking of applying, I would say that there is room to be yourself. Writing a PhD is not easy – it can be a solitary experience – but you have to have faith in your project and think it’s worthwhile for you. If I had to answer the question, ‘What makes for success?’ I would say, number one, I think successful people do the things they don’t want to do, and that means dealing with elements you might not be that excited about – like getting those footnotes done or tracking down a reference – because they’re for a bigger end. The second thing I would say is never get discouraged. You will fail, you will get things thrown back at you. But you’ve got to keep getting up to the plate and swinging the bat, because it’s only if you do that the successes start to ramp up.