Born in Salt Lake City in 1941 and raised on a farm in Missouri, astrophysicist and former American football player Joe Romig now calls Boulder, Colorado home. A player for the Colorado Buffaloes and elected to the College Football Hall of Fame in 1984, Joe has also enjoyed an illustrious scientific career, including time as a NASA scientist, a consultant in the fire investigation industry and a college lecturer. This narrative is excerpted from an interview with the Rhodes Trust on 28 August 2023.

Joseph Romig

Colorado & Wadham 1963

On growing up with chicken pens and church hymns

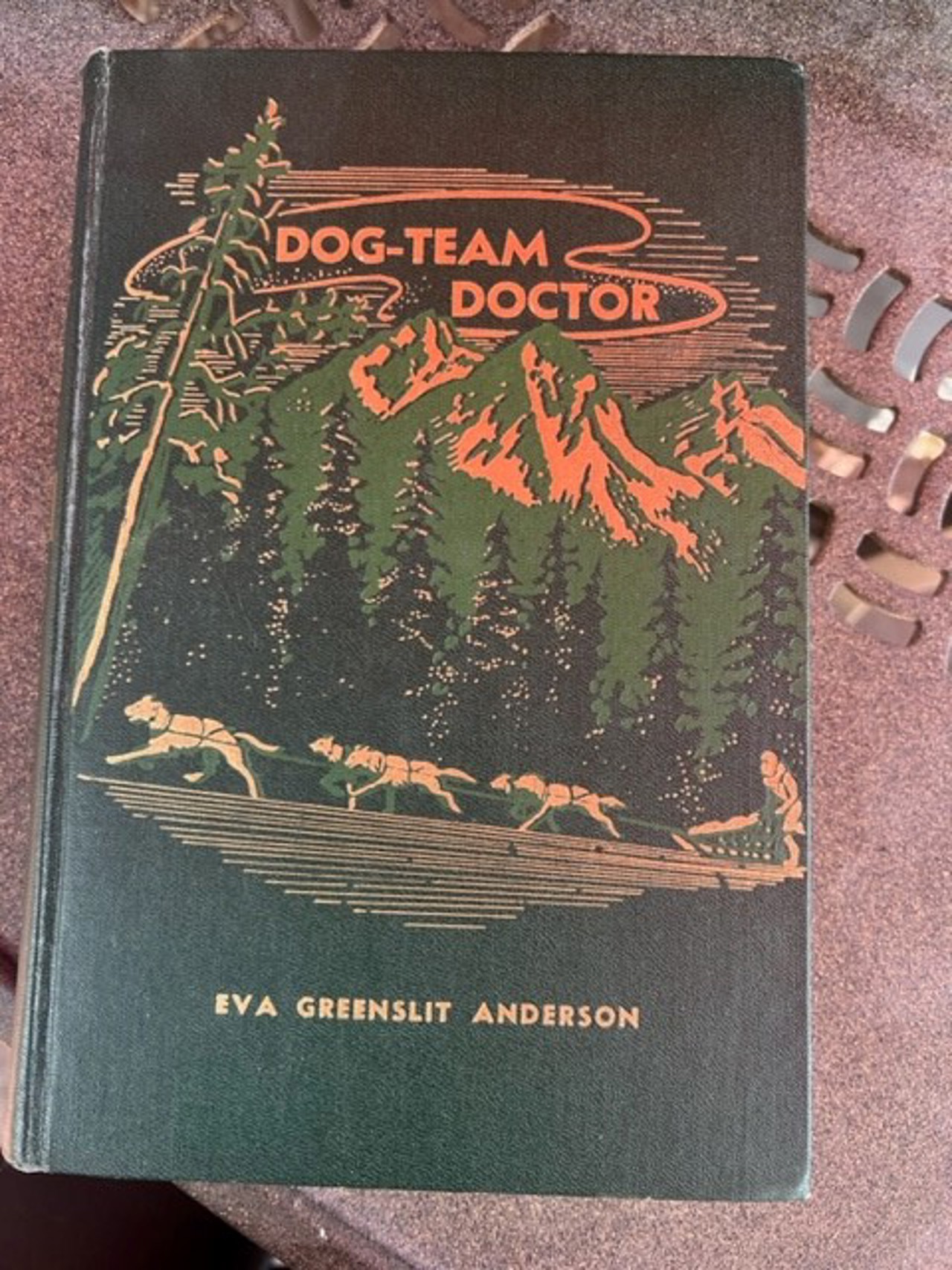

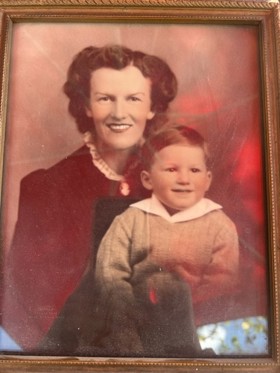

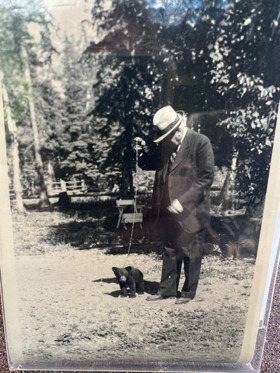

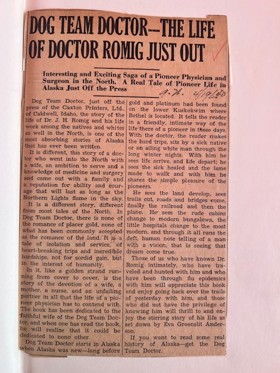

I grew up on my grandparent’s farm outside of Elsberry MO, and we were very poor. I can remember the outhouses and how they would plough the field with horses. I also spent a lot of time in Colorado Springs with my Grandfather Romig who retired there; he was one of the first physicians in Alaska. The Moravian Church had educated him and in return, he did medical work at their mission in Bethel. Those experiences that I had on the farm in Elsbury and with my Grandfather Romig in Colorado Springs were critical. While I was growing up, my mother was away, getting a nursing degree in St. Louis but she always believed in me, loved me, supported us with help from my father.

The only school that would let me in early, at age four, was Sacred Heart. And so, I had a background in Catholicism and also, a part of farm life is going to church, Baptist or fundamentalist. I would always enjoy the hymns and the ice-cream.

From the dawn of consciousness, I believed in God. And if anything didn’t go right, I would actually curse God. My aunt tells a story about when I was four and on the farm and my grandmother asked me to go feed the chickens. So, I went out and the chicken feeder collapsed, and I broke into a battery of swear words that my grandmother hadn’t ever heard. And she came out and said, ‘Joe, Joe, God wouldn’t like to hear you say those things.’ And apparently, according to my aunt, I looked at her and said, ‘Well, then, he can feed his own goddamn chickens.’

'I built my first telescope when I was ten’

My stepfather, Frank Moore, was a geologist. Because I had asked, ‘How far you can you divide things down?’ he gave me a book on the stars. This was 1950. Space stations, moon landings. So, I was keyed up. I built my first telescope when I was 10 and it was a cheap refractor, I just made a tube and put the lenses in and looked at the moon. I still remember that view.

‘Our coach said something I’ll never forget’

I wanted to be a great football player. We moved to Lakewood, CO and I went to Lakewood High School. And there, our coach was a tough ex-marine named Tom Hancock. I remember he said something I never forgot. He said, ‘There was a time when Lakewood took the field, that other teams feared them.’ And he said nothing more, but you could see that hit all of us, and we decided it was that time again. And so that was instilling in me the will to power, not only in football, but everywhere.

After high school, I wanted to go to the University of Colorado, because I’d been very interested in the building of their observatory. And then, they offered me a football scholarship. But I remember our freshman coach, who said, ‘Men, you can’t eat a football.’ So, I thought, ‘Well, you’d better get your education. But you’re on a football scholarship.’ So, that decided the two things I would focus on: I only played football and studied.

On applying for the Rhodes Scholarship

It was a pretty simple decision. I was obsessed with physics, but I hated having to take exams every week, and I thought to myself, ‘I’d like to get in a situation where I don’t have any.’ And I learned that Oxford had that system, and so I applied for the Rhodes Scholarship and was successful.

What I discovered in Oxford was the quality of education. My first year was also the first year that Rudolf Peierls came, and he was a great physicist and built up the physics department. Peierls was a German Jew and like many others – Lise Meitner and Otto Frisch, for instance – he chose not to stay in Germany. Frisch eventually ended up in Birmingham with Peierls, and they were the first to calculate the critical mass for an atomic bomb. And it was only half a kilogram or a kilogram. Heisenberg had used a different method and calculated it to be much larger and beyond the capabilities of the Germans in the war. I wish I’d have known that before I arrived in Oxford. I wish I’d have known about the history of Wadham College, too. That would be my advice to the current Rhodes Scholars: learn everything you can about the history of England and Oxford and your college and the people you will be working with, as well as the interactions that are occurring worldwide.

‘Those were great times, scientifically’

I came back and did my PhD in Astrogeophysics at Colorado University, and I was working in the advanced planetary programmes at Martin Marietta, now Lockheed Martin. Our team was tasked with determining what missions NASA was going to fund that we could propose. We won a number of contracts. But this was the mid-’70s and NASA’s funding was diminishing, and so they laid off our whole group. I thought to myself, ‘How can I use my education and experience to make a living?’ I was lucky to have a good friend who invited me to a meeting of venture capitalists, and through my contacts there I was hired to work on innovations.

That eventually got me involved with Ponderosa and fire and explosion investigation. And then I went out for Voyager 2 Mission, and we would go to the Jet Propulsion Lab during some of the encounter. And at the Uranus encounter, that was the Challenger disaster, we actually saw it on the screen.

When I was working on the Voyager Mission and still involved with projects in glass coatings and in fire and explosion investigation, I was also asked teach a freshman astronomy class for Continuing Education at Colorado University. So, there was a time I was working three jobs, and then two and then one. With fire and explosion investigation, I was applying the physics I’d learned, whereas on the Voyager, it was theoretical physics. And then teaching was kind of pulling that all together.

On being a forever learner

I retired from work in January of 2020. My wife, Barbara, still goes into work every day, in the museum at the university, and she once said to me, ‘While I’m at the university, I want you to be downstairs in the basement reading physics.’ And I said, ‘No problem.’ Well, she came in one morning from work and I had piles of papers all over the desk. She asked, ‘What’s that scribbling on that pile there?’ ‘I beg your pardon’, I said. ‘That’s mathematics, to put these ideas in mathematical form.’ She said, ‘Oh, you remind me of the guy in the movie.’ Well, since I was full of hubris at that point, I said, ‘Oh, you must mean A Beautiful Mind, right?’ She said, ‘Wrong,I was thinking more of Jack Nicholson in The Shining.’

I’ve been fortunate to have a companion who keeps my hubris on a reasonably short leash. And she is the reason for many of our connections at Oxford, with the Ashmolean, with Wadham, with the Department of Physics. Barbara really has an ability to network and connect in a meaningful way. And I might tend to be a loner, but with her, I can’t be. We’ve had a great 42-year marriage.

‘A singular opportunity’

I think Oxford provides a singular opportunity for a first-class education, interaction with people from different cultures, and actual time to travel. The first break after the first term, David Boren (Oklahoma & Balliol 1963), Rob Samson, Dan Rowland and I took a six-week trip to the Middle East. First, we took the boat across, then train through Switzerland. We ended up in Brindisi, Italy, which was the port. And I could see the worn marks in the limestone of the Roman legions that came and left. We went to Athens and you could still walk up into the Acropolis. We went to Delphi. We then went to Istanbul and the markets. And then to Beirut. Those were remarkable experiences.

‘The little intricacies’

At the Rhodes 120th Anniversary celebrations this year, I went to Professor Michael Sandel’s (Massachusetts & Balliol 1975) lecture on meritocracy. It set me thinking about all the little intricacies that have occurred in my life, the twists and turns, the fact that we are where we are because of a lot of random events that have occurred, good fortune, as well as hard work and intelligence. So, I made an analogy to a physics and mathematics problem that’s called ‘The Random Walk’. Now, if you listen to the fundamentalist ministers, they will say, ‘Straight is the path, and narrow the way.’ So, suppose that you began at a flagpole and you followed that exhortation and took 100 steps, then you’d be 100 feet in a straight line from the post, if each step is one foot. But if there are random events occurring after each step, you end up being the square root of n, which is 10. And I would characterise my distance from the flagpole as more like 10, rather than 100