Born in South Orange, New Jersey in 1937, Joseph Nye studied at Princeton before going to Oxford to read for a second BA in PPE (philosophy, politics and economics). He returned to the US to take up graduate study at Harvard and carried out much of the research for his PhD in Uganda, Kenya and Tanzania. Nye joined the faculty of Harvard in 1964. From 1977 to 1979, he was Undersecretary of State for Security Assistance, Science, and Technology and chaired the National Security Group on Nonproliferation of Nuclear Weapons, receiving the Distinguished Honor Award in recognition of his service. In 1993 and 1994, he was chair of the National Intelligence Council, and received the Intelligence Community’s Distinguished Service Medal. In 1994 and 1995, Nye served as Assistant Secretary of Defense for International Security Affairs, winning the Distinguished Service Medal with an Oak Leaf Cluster. From 1995 to 2004, he was Dean of the John F. Kennedy School of Government. Nye is the author of, among other works, Nuclear Ethics and a memoir, A Life in the American Century. He is a fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, the British Academy, and the American Academy of Diplomacy. This narrative is excerpted from an interview with the Rhodes Trust on 16 October 2024.

Joseph Nye

New Jersey & Exeter 1958

‘I always liked history’

I spent the first five years of my life in South Orange and then my parents moved to a very rural area at New Vernon, New Jersey, where we had an old house right in the centre of town, but with a farm of 100 acres behind it. My father worked on Wall Street, but he insisted that my three sisters and I all work on the farm. I loved growing up there and being outdoors became a lifelong passion. I still grow vegetables to this day.

At elementary school, I was a very indifferent student. When one of my teachers assigned me extra homework, I thought she was trying to punish me, so I’d just crumple it up and throw it away. It was only in ninth grade, when they announced the grades at the end of the first and I came second that I thought, ‘Oh, my gosh, if I can do that with no effort, maybe I’ll try harder.’ I always liked history, and at high school I had a terrific history teacher, which helped.

On applying for the Rhodes Scholarship

I was the only member of my year at school who went to Princeton, and although it was a nice experience, it wasn’t easy at the beginning. I was more or less on my own, which at least made me self-reliant. The best part about Princeton was that it placed a lot of emphasis on interaction with the faculty, and there were small group meetings with the professors who gave the lectures. That system helped to awaken me intellectually. I majored in what was then called the Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs, which was a mixture of history and economics and sociology.

At that time, all young men had to register for the draft, and I thought I would join the Marine Platoon Leadership Corps. Then, at the beginning of my senior year, I bumped into a former Rhodes Scholar, and when I told him about my plans, he said, ‘No, no, Nye, you’ve got to go for a Rhodes.’ So, I applied, and lo and behold, life took a twist. I remember driving back from the final interviews after learning that I had won and finding it hard to believe I was going to spend two years in Oxford.

‘I was motivated by exploration’

I sailed over to England with many of my Rhodes classmates, and that was a chance to really make some good friends. I lived in my college, Exeter, for both of my years at Oxford, and I shared a room with a man named Richard Buxton, who’d been to a British public school and was a great believer in a stiff upper lip and plenty of fresh air. He used to throw opne the windows in our freezing eighteenth-century room and I would think, ‘This is how the American Revolution is going to start again.’ But he and I got to be good friends, and today, he’s Lord Justice Buxton.

My tutors made me think hard about a number of things, so I found myself doing a little more work in my tutorials than I had originally planned. I was motivated by exploration rather than academic achievement, but somehow, I managed to get something of both. The Scholarship gave me the chance to explore the world, and I particularly remember travelling to eastern Europe and the Soviet Union in 1959, before it really opened up. We would arrive in a Russian town and it was like we had come from Mars: people wanted to know who we were and where we were from.

I spent a lot of time in Oxford trying to do creative writing. But I also had many conversations with a friend at Exeter named Kwamena Phillips, who was from Ghana. This was when Ghana had just become independent, and he would argue that Africans were going to create a new type of democracy. I found all this very heady stuff, and I thought it would be interesting to go on and learn more about it.

‘It was exciting to be able to transmit ideas outwards’

When I first went to graduate school at Harvard, I thought I might go on to join the Foreign Service. But then, I had a conversation with Edward Mason (Kansas & Lincoln), who had just come back from chairing the World Bank mission advising Uganda, and that gave me the idea for my thesis, which eventually became a book called Pan-Africanism and East African Integration. Harvard offered me an instructorship, and I thought, ‘Well, I’ve enjoyed the teaching I’ve done. Maybe I’ll try this for a little while,’ never imagining that the little while would extend to over half a century.

The chance to go into government occurred in 1976, when Jimmy Carter was elected as a Democrat. By then, I’d become identified as a Democrat, even though I’d started out as a Rockefeller Republican, a breed that’s long gone now. I was appointed to be Deputy Under Secretary of State, in charge of Carter’s policy on non-proliferation of nuclear weapons. That was a new experience for somebody who had basically been within an academic institution, and I learned that you can’t do it by yourself. You’ve got to attract other people to want to help you by having a vision and saying, ‘Here’s a direction.’ I’ve joked that my academic and political lives are a kind of trade-off between omniscience and omnipotence. Obviously, I’ve had neither, but both spheres have given me different ways to follow my curiosity. When I wrote Bound to Lead, for example, I was trying to calculate how much power the US had. I did the usual balance of military power and economic power, and I said, ‘There’s still something missing.’ That was how I developed this concept of soft power, which has taken legs beyond what I expected. It taught me that you can’t predict what will happen as a result of the work you do.

Under the Clinton administration, I was given the chance to chair the National Intelligence Council, which led to a fascinating period and some very interesting travel abroad. Then, in 1995, I was asked about Whether I’d be interested in becoming Dean of the Kennedy School of Government. My first reaction was ‘No,’ because I was working in government on the initiative to rejuvenate the relationship between the US and Japan. But this was April 1995, just after the Oklahoma City bombing, and I decided that I wanted to think about the larger question of why some people didn’t trust government. At the Kennedy School, we started a faculty project to look at that. Like so much of what I’ve done in life, it was in no way what I would have predicted, but it was exciting to be able to transmit ideas outwards in that way.

‘Follow your curiosity’

I don’t think you can plan out everything in your life, and that’s going to be particularly true for younger Rhodes Scholars. They’re going to have to deal with extraordinary changes in technology, with artificial intelligence and the questions that are related to that. There have been enormous changes in technology in my lifetime too. There were no computers when I was born, and nuclear weapons were created when I was eight years old. Those two things made a huge difference to the world, and I tried to spend some of my career understanding them and doing something about them. To today’s Rhodes Scholars, I would say: follow your curiosity. Explore the things that puzzle you and then try to do something about them.

Throughout my career, the most important thing has been my relationship to my wife and my three sons. Beyond that would be my relationship with my friends and students, beyond that would be the various things I’ve written, and beyond that would be the major policy issues that I’ve had an effect on. But the one that’s at the core of all that set of concentric circles is that family one.

Transcript

Interviewee: Joseph Nye (New Jersey & Exeter 1958) [hereafter ‘JN’]

Moderator: Jamie Byron Geller [hereafter ‘JBG’]

Date of interview: 16 October 2024

[file begins 00:03]

JBG: This is Jamie Byron Geller on behalf of the Rhodes Trust, and I am here with Professor Joseph Nye (New Jersey & Exeter 1958) to record Professor Nye’s oral history interview, which will help us to launch the first ever comprehensive Rhodes Scholar oral history project. Today’s date is 16 October 2024. And Professor Nye, before we begin, would you mind saying your full name for the recording, please?

JN: Joseph S. Nye, Jr., and resident of Lexington, Massachusetts.

JBG: Wonderful. And Professor Nye, do I have your permission to record audio and video for this conversation?

JN: Yes, absolutely.

JBG: Great. So, you mentioned, Professor Nye, that we are having this conversation on Zoom, but are you in Lexington at the moment?

JN: I am indeed. I go into Cambridge, to Harvard, one or two days a week, but I basically reside in Lexington, the birthplace of the American Revolution, I should say.

JBG: Yes. How long has Lexington been home for you?

JN: Well, we moved to Lexington when I was an assistant professor at Harvard, and we had our second child coming, and my wife said, ‘We can no longer afford to move or to live in Cambridge, right?’ Rents were too high for a young assistant professor. So, we moved to Lexington. We’ve lived in Lexington for over 50 years.

JBG: Wow.

JN: We were lucky to get a house right on the old historic Battle Green. So, our kids grew up thinking people marching around in colonial uniforms and firing muskets was normal.

JBG: And what about you yourself, Professor Nye? Where were you born and when?

JN: I was born in South Orange, New Jersey, and I was born at home, because there was a flu epidemic at the time, in 1937, and the hospitals were full. So, I was born at home and spent the first five years of my life in South Orange, New Jersey, and then my parents moved to a very rural area, 30 miles west of that, at New Vernon, New Jersey, where we had an old house right in the centre of town, but 100 acres behind it, which was an illustration of how rural it was.

JBG: Wow. Wow. And I would love to know more about your experience growing up in that environment. What was your childhood like?

JN: well, I loved growing up outdoors, and my father worked in Wall Street, but had a professional manager for the farm, but he insisted that my three sisters and I all work on the farm, and it was something that stuck with me. I still grow vegetables to this day. And the one downside of it was, if you live in a small area like that, there are not a lot of other kids to play with. So, I was never on football or baseball teams, because there weren’t enough kids for a team. But I spent a lot of time out working in the woods and the fields, and that became a lifelong passion.

JBG: And what were your earliest educational experiences like, in elementary and then high school?

JN: Well, I went to Harding Township Elementary School, which was-, you walked about half a mile up the road and there was this old schoolhouse, and I was a very indifferent student. I mean, I was certainly not academically motivated. In fact, my attitude was, ‘Do just enough to get by,’ and when one of my teachers told my parents that she was assigning me extra homework, my reaction to that was not, ‘She’s trying to develop me,’ ‘She’s trying to punish me,’ and why did I have to do it? The other kids didn’t. So, I’d crumple it up and throw it away. And it wasn’t really until ninth grade, when I went to school in Morristown, the county seat, which is about seven miles away, that I discovered that I could actually do academics pretty well, and when they announced the grades at the end of the first term, I had come in in second place, and I thought, ‘Oh, my gosh, if I can do that with no effort, maybe I’ll try harder,’ and from that, I was able to come in in first place. So, for students, or parents of students who see their children underachieving and worry about whether they’re having a major problem, every child learns at its own pace. And so, I think the moral of the story is that I began as a slow learner.

JBG: And in high school, as you started to perhaps gravitate more towards academics and spend more time on your schoolwork, were there particular subjects that you found yourself gravitating towards during that time?

JN: Well, I always liked history, and I had a terrific history teacher, which helped. And so, I spent a lot of time on history, but also, going to school where there were a lot of other kids, I discovered that I liked athletics, and so, I played football and ran track. But, you know, going from a very small school to a somewhat larger school – still small – was a very broadening experience.

JBG: And I’m curious if, during your childhood, Professor Nye, you had a sense of the direction that you hoped your career might take, or what you hoped to do professionally when you grew up.

JN: Well, not really. I mean, I went through different phases of what I thought I might do when I grew up. At one point, given my interest in the outdoors, I wanted to be a forest ranger. At another point, I thought I might become a minister in the Presbyterian church that we went to, which was right across the street from our house. And then, after that, I thought, ‘Well, maybe I’ll go into business like my father did.’ And so, obviously, none of these things panned out. So, again, when younger people say, oh, you know, ‘I’m a freshman, or a sophomore, and I don’t know what I want to do,’ I say, ‘Don’t worry about it. I still don’t know what I want to do.’

JBG: And did you go right from high school to college, after you graduated?

JN: I did, yes.

JBG: And you went to Princeton, is that right? About 40 miles.

JN: I started Princeton as the only member of my school who was there, and whereas a lot of the other kids were from schools like Deerfield or Andover, St. Paul’s, where you’d have a dozen or more people, all from the same school, so, they had a lot of friends to start with, I was more or less on my own to make new friends. And at first, it makes you a little bit lonely, but actually, it also makes you more self-reliant. So, Princeton was a nice experience. I liked it very much. But it wasn’t easy at the beginning.

JBG: How far was Princeton from where you grew up in New Jersey?

JN: Yes. The best part about Princeton when I was an undergraduate was that it placed a lot of emphasis on interaction with the faculty. And so, they had a system called ‘Precepts,’ which meant that the professor who gave the lectures would often meet with small groups of seven or eight students to discuss the material, and I found some of this stuff really interesting. I was taking a sophomore concentration course in anthropology, not because I wanted to, because I had to fill that box. And I would go to these precepts, and I said, ‘Boy, this is really interesting.’ And later, when I went to study for my PhD in Africa, I realised that the man who’d been teaching it, [10:00] Paul Bohannan, was one of the leading Africanists in the country. And here, as a sophomore, I was able to have him with just seven other students.

JBG: Wow.

JN: So, essentially, that system helped to awaken me intellectually, even though I didn’t do a lot to seek it out. I mean, it wasn’t that I was the student who is precocious and looks for the professors. The Princeton system brought the professor to the students. I’ve often said to friends who ask about whether they should send their child to Harvard, where I’ve taught for most of my career, or Princeton, I’ve said, ‘Well, if your kid is mature enough at age 17 or 18 that he or she can basically make selections all by themselves, just like going to a smorgasbord and knowing what to pick or choose, then go to Harvard, because it’s a bigger smorgasbord.’ But if you’re like I was, immature at age 17, having something that helped you plan and more access to faculty was, I thought, very important.

JBG: Yes. I’m so sorry if you said, Professor Nye, but what was your major at Princeton?

JN: I majored in what was then called the Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs. And so, it was a mixture of history and economics and sociology. And then, when I went to Oxford, I did PPE: philosophy, politics and economics. So, I’ve been caught in that trap for a long time.

JBG: And perhaps you’d heard about it before, but I’m curious about when in your journey at Princeton the Rhodes Scholarship became something that you started to think about for yourself.

JN: Well, I knew a lot of friends a year or two ahead of me who’d won Rhodes Scholarships, but I didn’t really think that I was going to apply at that stage. All young men had to register for the draft, and so, I thought, ‘Well, after I graduate, I’ll get this out of the way.’ And my wife’s cousin had been in the Marine Platoon Leadership Corps, so, I thought, when I was in the beginning of my senior year, ‘That’s what I’ll do.’ And I bumped into Professor E.D.H Johnson, a former Rhodes Scholar one day, in the library, and he said, ‘Nye, what are you doing next year?’ I said, ‘Well, Sir, I’m going to join the Marine Platoon Leadership Corps,’ and he said, ‘No, no, Nye, you’ve got to go for a Rhodes.’ And so, I applied, and, lo and behold, life took a twist.

JBG: Do you recall, Professor Nye, the moment that you learned that you’d been selected for the Scholarship?

JN: Well, I do. I had to go down to Philadelphia. I was living in New Jersey and I had to drive down to Philadelphia for the finals of the regional competition. Then, driving back, I said, ‘My gosh, this is real,’ but I found it, you know, very hard to believe that I was going to spend two years at Oxford. So, it was quite an enlightening experience to say, ‘Well, you can do this.’

JBG: Yes. And I know that you set off for Oxford in the fall of 1958. [pause 14:13-14:20] So, I was just saying, I know we spoke last time, Professor, about your experience sailing over with your class, and I was wondering if you would mind speaking about that a little bit.

JN: Well, in those days, we were encouraged to have our class sail together, and we sailed together on the Queen Elizabeth, from New York to Southampton. And so, you’d spend, you know, five days or so with your future classmates of that Rhodes class, and it gives you a chance to really make some friends, to find out people you don’t want to see that much of, and also to have a very good time. I recount this in my memoir, that I was asked by the Rhodes group to approach the captain of the Cunard ship, and ask for permission to use the first-class gym. And so, I got a note saying, ‘Come to the captain’s quarters at-,’ I don’t know, four, or something. I thought, ‘Well, he’s going to hand me the key to the gym.’ Kind of a dumb thought. But when I got to the door, I knocked on it. I was ushered into a cocktail party where everybody else was in coat and ties, and I was in shorts and a t-shirt, because I thought I was going to get a key to the gym. And I thought, ‘What do you do in a situation like that?’ And you just pretend that, you know, the emperor has clothes on, or that you’re properly dressed. But eventually, we did get the key to the gym, but it wasn’t through that call on the captain.

JBG: Had you spent time in the UK previously?

JN: I’d been on a visit once. In fact, ironically, I was in London for just a day or two and I thought, ‘Well, I’ve heard a lot about Oxford and Cambridge, or Oxbridge,’ and so, I went to the station and said, ‘I want to take the train to Oxford and Cambridge,’ and the Englishman behind the ticket counter looked at me and says, ‘Laddie, you got to choose one or the other. They’re not near each other.’ I said, ‘Okay, which one do you recommend?’ He said, ‘Oh, Cambridge, it’s much more beautiful.’ So, I took the train to Cambridge and looked around the colleges. I thought, ‘Yes, it is beautiful,’ and, lo and behold, wound up at Oxford.

JBG: And so, the experience of arriving with your class was the first time you’d been in Oxford.

JN: Yes. And it was-, you know, Oxford is stunning in its beauty as well, but the irony of having made that choice when I was in college, kind of, shows that life is full of surprises.

JBG: And did you live at Exeter both years that you were in Oxford?

JN: I did. I lived in college, and Kenneth Wheare (Victoria & Oriel 1929), who was the Rector of Exeter, an Australian Rhodes Scholar, had the belief that it would be good for the Americans to share a room with a British student. In this case, I was paired with Richard Buxton, who’d gone to a public school, in the British sense of the term, and served in the British Army in Gambia. And he was a great believer in stiff upper lip and fresh air, and so forth, and I was trying to adjust to the fact that the beautiful eighteenth-century room with all its panels and so forth was heated by a little grill in the blocked-up fireplace. So, you put a shilling in, and it turned on the grill for an hour or so and warmed the room. So, I’d pull up my chair right in front of that, put a blanket over me, study there, and Buxton would come back from whatever he’d been doing and thrown open the windows, and he said, ‘We need fresh air.’ And I thought, ‘This is how the American Revolution is going to start again.’ But in fact, he and I got to get to be good friends, and today, he’s Lord Justice Buxton.

JBG: Wow. Wow, that’s incredible. And how did you find the experience of reading PPE at Oxford, compared to your experience at Princeton, the differences between those academic experiences?

JN: Well, in an American university, including the Wilson programme at Princeton, you’re examined every [20:00] term and the courses are pretty much set for you. As you know, in Oxford, you’re examined after the end of three years, or two for the American Rhodes Scholars, and you can go to a tutorial and prepare yourself well, or you can basically blow it off by writing a crummy essay, and you can either go to lectures or not go to lectures, depending on what you want. So, it’s a much more independent experience. But I found that the tutorials were-, I liked my tutors, they were very good and made me think hard about a number of things. So, I found myself doing a little more work in my tutorial than I originally had planned.

I was also the secretary of the Junior Common Room and I was playing on the second rugby team, and so, I had a lot of activities besides academics that were going on. But I found that these tutorials were really very interesting, and being able to argue back with a professor one-on-one, as it was in those times, or a don, was a great educational experience. So, I found that the Oxford experience, academically, was very good. But it’s also true that I had done well at Princeton and graduated summa cum laude, and I said, ‘I don’t want to spend my two years at Oxford just doing that again. I want to explore the world, both intellectually and physically,’ and so, I was motivated by exploration and not by academic achievement, but somehow, I managed to get something of both.

JBG: And I recall you sharing, Professor Nye, in our last conversation, the way in which your Rhodes experience and Oxford experience really was a time at which you felt like your horizons were broadened, and I was wondering if you would mind sharing more about that, and perhaps in the context of your travel experiences as well.

JN: Well, I widened my horizons intellectually and also by travel. But, I mean, I used to buy books which were introductions to ballet, or introductions to classical music, or things like that, and I remember sitting out in the garden at Exeter, reading these things, just because I knew nothing about them and I wanted to learn about them. So, in that sense, I was exploring a lot of areas which had nothing to do with philosophy, politics and economics. But the travel was very important to me. The fact that Oxford has the long vacations, six weeks between terms, gives you ample opportunity to travel. I found that very enlightening.

I spent a good deal of time on the continent, but I think probably more interesting, with that, were trips to North Africa, to Morocco, and probably the most intriguing was a trip to eastern Europe and the Soviet Union in 1959, which is before it really opened up. And two other Rhodes Scholars and I drove in a little British Sunbeam Rapier, something that doesn’t even exist anymore, and we entered in from Finland and eventually exited through Warsaw and then Budapest and Prague, and finally wound up in Vienna. And it was like being creatures from Mars: you pull up into this small – or large – Russian town and you’d be crowded with 40 or 50 people wanting to, what were you? Where did you come from? And then, when they discovered you were American, they’re asking, ‘Why do you have us surrounded with hostile bases?’ And someone would say, ‘Do you believe in God?’ At that time, atheism was the official position in the Soviet Union. And in the evenings, we’d go to these parks of culture and rest, which were open-air parks where young people gathered, and the boys would challenge us to things like hitting a hammer to ring a bell, you know, throwing-, and the girls would ask us to dance, and it really was like being a creature from Mars. Fortunately, one of the three of us, John Sewall (New Hampshire & Brasenose 1958), who was a West Point Rhodes Scholar and therefore a second lieutenant, also rowed in the first boat for the Oxford crew, so, he could always win these contests. I couldn’t win.

JBG: You shared that prior to college, as you were growing up, what you envisioned for your career might have been a little amorphous, or that you were not sure what direction that would take, and I’m curious if that came more clearly into focus when you were in Oxford.

JN: Yes. I mean, in Oxford, at one point, I thought I was going to become a novelist, and, in fact, I wrote a first draft of a novel, which, as-, I showed it to professors and friends, later, who said it was pretty awful. Finally, I published a novel in 2004, called The Power Game, which at least got good reviews, but didn’t make me a novelist. In the meantime, I’d become a professor and a government official. But at the time, at Oxford, I spent a lot of time trying to do creative writing, and I didn’t know what I was going to do.

But I had a friend at Exeter named Kwamena Phillips, from Ghana, and this is a time when Ghana had just become independent, in 1957, and he and I would sit after dinner, in the dining hall, and talk about what was going to happen in Africa, and he would argue that Africans were going to create a new type of democracy and they were going to escape their colonial cages that had been imposed on them by the Europeans and have a pan-African union, and I found all this very heady stuff, and I thought it would be, kind of, interesting to learn more about that or do more about it.

So, when I went to Harvard-, well, that led me to decide to do graduate school at Harvard, as a way in which I might join the Foreign Service. When I was in graduate school, Edward Mason (Kansas & Lincoln 1919), had just come back from chairing the World Bank mission to advise Uganda on what it should do as it became independent, and he said, ‘The British have given them a common market, with Kenya and Tanzania, of roughly 30 million people, and they’ll do a lot better than if they just rely on the eight million people of their home market,’ as it was at that time. And he said, ‘But nobody knows if they’ll be able to keep it, and I’m an economist. It would take a political scientist to figure this out.’ I thought, ‘There’s my thesis topic.’

So, I applied for a Ford Foundation grant and went and lived in Uganda and Kenya and Tanzania, interviewing local politicians for a year and a half, and wrote my thesis, and it eventually became a book called Pan-Africanism and East African Integration. So, you know, did I think that I was going to do that when I started at Oxford? Absolutely not. On the other hand, after I had gone to Africa, I remember receiving a letter when I was at Makerere East African Institute of Social and Economic Research, in which Harvard wrote to me and said, ‘We’re offering you an instructorship for the magnificent salary of $6,000 [30:00] a year.’ I thought, ‘Well, I’d enjoyed the teaching I’d done as a graduate student. Maybe I’ll try this for a little while,’ never imagining that the little while would extend to over half a century. So, it shows you I’m not very good at planning my future.

JBG: What year was that, when you started your first professorship at Harvard?

JN: Well, I came back from Oxford in 1960. I did my graduate work, including the year and a half in Africa, and then was given the instructorship in 1964. So, I started as a Harvard faculty member in 1964, and I finally retired as an emeritus professor in, I guess, it was 2017. So, that’s a lot of time.

JBG: Wow. Yes. Would you mind sharing a little bit about those earliest years of your career at Harvard?

JN: Well, when I first came to Harvard, in 1960, John F. Kennedy had just been elected president, and there was enormous excitement. A lot of Harvard faculty members were going down to Washington to be part of the New Frontier and there was a feeling that things were going to be very different politically. The Eisenhower era had been, basically, calm, but some people felt, too calm, and Kennedy ran on the idea of shaking things up. And so, in the early stages, there was a lot of interest in politics, in Washington politics, and I participated in that, but I didn’t become politically active. I didn’t work in campaigns or ring doorbells or anything. I was just interested as a citizen, and I was also trying to do my general examinations, where you are examined for two hours by professors like Henry Kissinger, Stanley Hoffmann, and so forth, and so, I had to keep my head down, trying to master the books that were essential to read for that.

And then, lo and behold, I missed a deadline, so, I didn’t get my fellowship renewed – it was a graduate student fellowship – and I said to the chairman of the government department – I waited until I had my first term grades – ‘I didn’t think you’d give me a renewal until you saw that I got all As,’ and he said, ‘Oh, it didn’t matter what your grades were, it’s whether you got your application in by 1 February or not.’ He said, ‘But we’ll allow you to teach, as a teaching fellow, before your generals. So, it was a rough second year. I’d just gotten married, I’d just lost my academic fellowship, and I was teaching and acting as a research assistant to a professor while trying to prepare for these rigorous general exams. But that was a weird year-, I was interested in politics, but I had no time to participate actively.

JBG: And I’m curious, when you were starting your career at Harvard, if government service was something that you were thinking about as part of your career at that time.

JN: Oh, yes, definitely, I had gone to do the PhD because I thought I’d go into the Foreign Service, and I thought it would be useful to have a PhD before I went into the Foreign Service. So, I had been thinking of government service since I came back from Oxford, but, you know, I didn’t have a clear plan. And I remember going to Richard Neustadt, who was a senior professor at that time, who was close to Kennedy, and asking him, ‘If I want to do government, service, shouldn’t I go in and try to participate now?’ and Neustadt said, wisely, ‘Nail down your academic credentials. Write a book, write some peer-reviewed articles, make yourself well known and get tenure, and then go into government.’ And that’s what I did. I followed my time in Africa by research in Central America, and then I went and did research based in Geneva about the European common market, and I published books, you know, that received good reviews, and then I got tenure in, this must have been 1971.

But, you know, the chance to go into government occurred in 1976, when Jimmy Carter was elected as a Democrat. By then, I’d become identified as a Democrat, even though I’d started out as a Rockefeller Republican, a breed that’s long gone now. But when Carter came in, in 1976, I was asked to work on the transition team, and then I was appointed to be deputy under secretary of state by Cyrus Vance in the Carter State Department, in charge of Carter’s policy on non-proliferation of nuclear weapons. So, yes, I was interested in government service, but instead of coming up through the ranks of the Foreign Service, as originally planned, I was, sort of, parachuted in from a political level, even though I hadn’t done all that much in politics.

JBG: To the degree that you’re able to share, Professor Nye, would you mind sharing about that experience working in President Carter’s administration?

JN: Well, I was put in charge of Carter’s non-proliferation policy. I was chairman of the National Security Council ad hoc committee on non-proliferation of nuclear weapons, which meant I could call meetings from all different departments – Pentagon, Energy. Well, it was then ERDA, but became the Energy Department – as well as different parts of state. And that was a new experience from somebody who had basically been within an academic institution, and I had a large number of people reporting to me. And when I was at Harvard, I used to say I had one person reporting to me, and that was my secretary, and some people would say, ‘You got the sign wrong. You were reporting to her.’

So, to go from doing everything yourself, so to speak, to running a complex policy within the State Department and across government bureaucracies was on-the-job learning, and one of the things I learned is that you can’t do it yourself. You’ve got to attract other people to want to help you, and you do that by having a vision and having the energy to say, ‘Here’s a direction.’ It’s intriguing that, if you leave things to the bureaucracy, to work its normal way, you get products that aren’t terrific. You get the compromises that are normal in a bureaucracy. And then, you get a product that’s handed in to you that’s been tasked out and you say, ‘Oh, this is pretty awful,’ and you sit down and you try to rewrite it yourself, and you realise you just can’t do it. I mean, you’d get home from work around [40:00] nine or ten at night, and then you were due up at seven a.m. to be at a seven-thirty staff meeting with the secretary of state. There’s no way you can do the things you would do as an academic.

So, I had to learn how to delegate, and delegate not simply in the sense of having them do it, but to delegate and then lead, to give them a vision, to keep on top of the process so that they want to do things. And it was, again, a learning process. But after my two years, you know, I got the State Department’s highest commendation for the work I’d done on the non-proliferation policy. So, it’s like being thrown into the proverbial swimming pool, and say, ‘Swim, or drown.’ Fortunately, I swam.

JBG: And did you and your family move to DC during those years, or were you commuting back and forth from Massachusetts?

JN: Well, at the beginning, we were commuting, because our three sons were in public school in Lexington, Massachusetts, and so, my wife stayed with them. And then, after school got out in June, we all moved down to Hollin Hills in Virginia, outside of Washington, and the kids went into the local public school there. It was a good experience for the family, but it’s also true that when you take young adolescent children and to move them, they complain a lot. But I think, in the long run, it was good for them.

JBG: And then, what year did you come back to Harvard?

JN: Well, I came back after two years, so, that would be early 1979. And I was tempted to stay in Washington, but I remember my wife and I taking a long walk and talking about whether I should stay in Washington. I’d been offered another job, which was a promotion, if I’d stay. And then we thought about what would be the effects on the family: we thought, really, it would be better for the kids to go back to their friends in Lexington and their peers and that environment. And my wife, who is interested in art, had been a docent at the Corcoran Gallery, and so, was quite happy at Washington, but I think both of us decided, ‘Well, go back, let the kids finish their high school years in Lexington, and then we can come back to Washington.’ Little did we know that there wouldn’t be another Democratic administration until 1993, and so, going back for just a few years turned out to be more than a decade. But I don’t regret it in the least. I mean, the most important thing in my life is my relationship to my wife and my three sons. We’re all very close. So, that, and the work that she put in was well worth it.

JBG: What did your work at Harvard look like during that time? So, you’d become tenured before moving to Washington, and the writing that you’ve done, Professor Nye, is incredible, so I would have to imagine that was a large focus of your work during that time, in addition to your teaching, and I would love to know more about those years back at Harvard.

JN: Well, before I went to Washington, Robert Keohane and I had developed a theory of complex interdependence and published a book called Power and Interdependence, which is still in print and read to this day, and that, I think, was an important piece of work, the fact that it has had that longstanding effect. But when I came back from government, I was very much intrigued by this nuclear weapons question, having spent two years trying to stop the spread of nuclear weapons. And very often, when I’d go to a country and say, ‘You shouldn’t have nuclear weapons,’ they’d say, ‘Why? You have them,’ and I thought I should answer that question to my own satisfaction, like, ‘When I’m a State Department official, I don’t have time to answer that, but when I get back to Harvard, I’m going to figure that out.’

So, when I came back to Harvard, I taught a graduate seminar called “What are the Ethics of Nuclear Weapons?’ and eventually, I published a book called Nuclear Ethics, which I still like very much in terms of the argument. That was the first part of my return to Harvard. That also was the period of the Reagan administration, of what’s sometimes called the Second Cold War, the intensification of the Cold War, and you found that, you know, large crowds were marching through the streets, demanding a nuclear freeze, and there were real worries about the possibility of nuclear war. So, with colleagues at the Kennedy School, I worked on a project which we called the Avoiding Nuclear War Project, and that produced a couple of books on, how can you reduce the risks of nuclear war? So, much of the 1980s, I spent trying to think about the nuclear issue, and in that time, I wound up starting a series of periods of visiting Moscow and the USA Institute in Moscow, or “the Arbatov[cannot decipher] Institute.” So, I think I went to Russia, or the Soviet Union, as it was then, about eight times, usually for a week or so at a time, and at the beginning, there was a fair amount of hostility. By the end, we were having meetings where we were revisiting the Cuban missile crisis with the American participants and the Soviet participants. So, we were running meetings where you had people like Bob McNamara and Ted Sorensen and Andrei Gromyko and Anatoly Dobrynin, who had all been participants at the time, thinking back over that period, asking, ‘What did we get right? What did we get wrong?’ and then trying to draw lessons from that. So, we came a long way over that period, in terms, not of solving the nuclear problem, but of having a better idea of its dimensions and how to reduce risks.

So, that was much of my intellectual life in the 1980s. By the end of the 1980s, I worked in the Dukakis campaign in 1988, and probably would have gone into government at some high level if Dukakis had won. TIME magazine even had an article saying I would be the national security advisor, but no one remembers that, because George H.W. Bush won. There was a lot of writing at the time about the decline of the United States. Paul Kennedy, the great British historian and a friend, had written a New York Times bestseller called The Rise and Fall of the Great Powers, which said the United States was going the way of Philip II of Spain or Edwardian England. I thought this was wrong, and so, I decided to write a book, which was eventually published, with the title Bound to Lead: The Changing Nature of American Power.

And as I was trying to calculate how much power the Americans had, I did the usual balance of military power and economic power, and I said, ‘There’s still something missing, which is the ability to get you what you want through attraction rather than coercion or payment.’ And in trying to explain that, I developed this concept of soft power [50:00], and that was first published as part of this book, Bound to Lead, but it was published, or developed, as an analytical concept, trying to round out the picture of American power and why I thought it was not in decline, but the concept took legs beyond what I expected, and, particularly, I was amused in 2007 when Hu Jintao, the head of the Communist Party in China, gave a speech saying that China had to invest more in its soft power. A little later, the Chinese foreign minister asked me to have dinner with him one-on-one to talk about how China could increase its soft power. So, a concept that developed as trying to understand an analytical problem while writing notes on my kitchen table in 1989, became something that came out of the mouth of the president of China.

JBG: Wow.

JN: So, it’s, again, an example of how you often can’t predict what things will happen.

JBG: Wow.

JN: Anyway, that period, of the end of the 1980s and early 1990s, I was working on American foreign policy and these theories of decline and the role of soft power. And then, in 1993, I was invited to join the Clinton administration, and I was given two offers, one of which was to be an assistant secretary of defense under Les Aspin, who is a friend who I got to know through our Aspen Strategy Group, which we founded in the nuclear period in the 1980s, and then, the other offer was to be chairman of the National Intelligence Council, which produces national intelligence estimates for the president, and that was chaired by the CIA director of national intelligence, Jim Woolsey. And I went back and forth about which of those to do, but I decided I’d do the National Intelligence Council job, and that led to a fascinating year and a half in intelligence, including very interesting travel abroad.

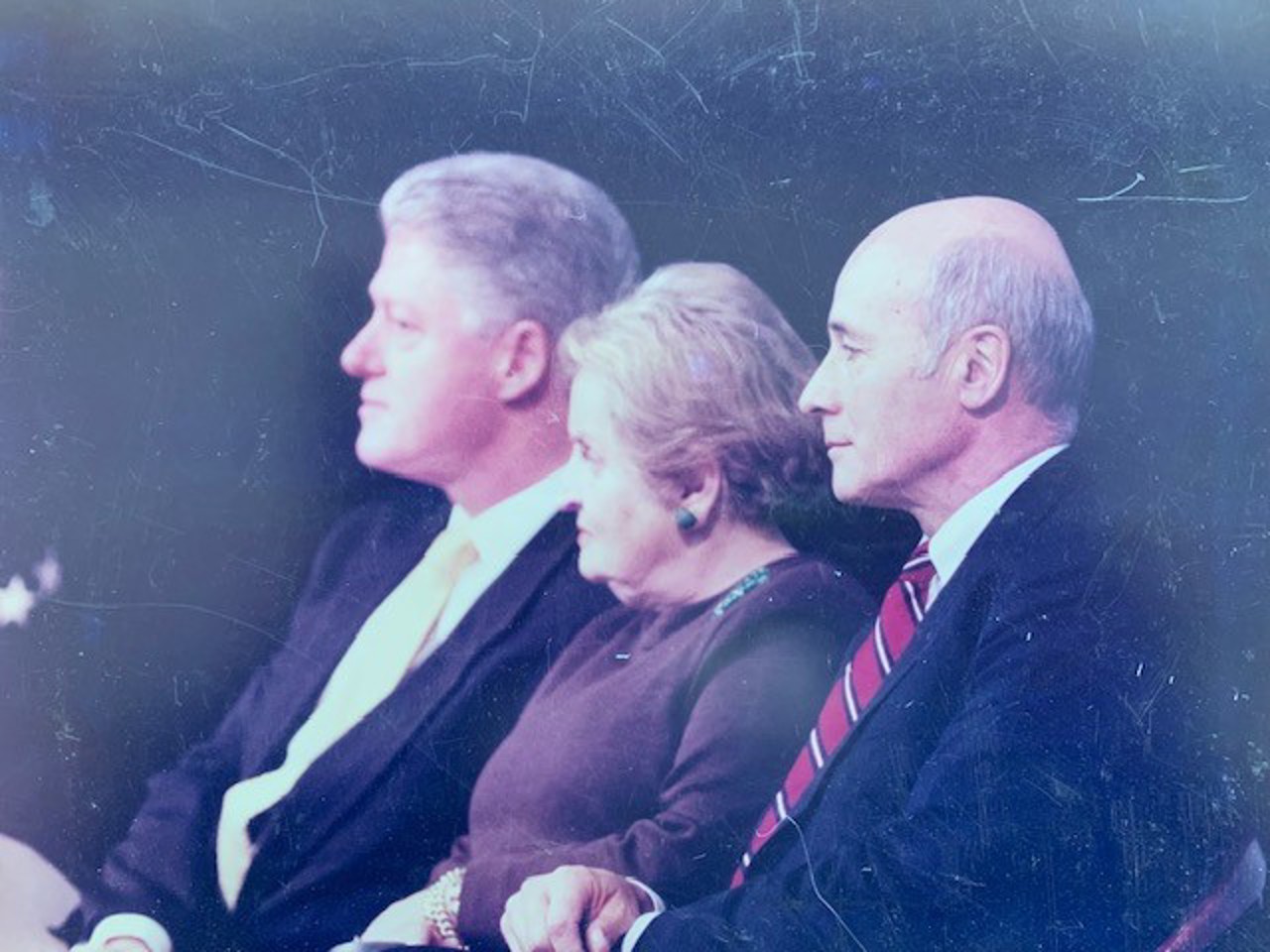

But then, halfway through my three years in the Clinton administration, I was asked if I would be willing to switch to the Pentagon, to the Department of Defense, as assistant secretary for international security affairs. I accepted because I felt that the American policy toward Asia, and, particularly, allowing the alliance with Japan to atrophy, was a big mistake. And when you’re in intelligence, you can believe that but can’t do much about it. Like a Victorian child, you can look but not touch, or be seen, but not heard. And when you go into the executive branch in the Pentagon, you can try to drive policy. And so, that period of trying to change American policy toward Japan at first, and then Asia as a whole, was called by the Japanese the Nye Initiative, but it led, in 1996, to President Clinton (Arkansas & University 1968) and Japanese Prime Minister Hashimoto issuing a declaration saying that the US-Japan security treaty was the basis for stability in the post-Cold War period. And that’s a big distance from 1993, when people in Tokyo and Washington both thought that the US-Japan alliance was the relic of the Cold War and should be abandoned or dropped. I’d go to meetings in the Situation Room in the White house where everybody was saying, ‘How can we beat up on the Japanese?’ and I thought this a mistake, but the question was, if China was a rising power and there were going to be three major powers in Asia – the US, China and Japan – it was better to be part of the two than the one, and therefore reaffirm the US-Japan security treaty rather than tearing it up. And at first, those views of mine were not very popular, but eventually we got that policy changed.

JBG: Wow. I’m curious, Professor Nye, thinking back to something that you shared in our last conversation, I think you mentioned that your work led you to 53 countries in 50 weeks, was it?

JN: Yes.

JBG: And you reflected really beautifully about how proud you were of having held your family during that time, and I was wondering if you would mind speaking to that. So, was that during your time at the National Intelligence Council.

JN: Now, that was basically in the Pentagon. As assistant secretary for international security affairs, I was the Pentagon’s little state department, responsible for our relations with defence departments and the military in all other countries except for the former Soviet countries. That meant a lot of travel. And so, you know, Latin America, Africa, Europe, many times. I mean, that’s why I wound up going to 53 countries in 52 weeks. I don’t recommend that. It’s not like tourism, but it’s a lot of work. On the other hand, it’s not dull, either. But the important thing, as you mentioned, was that we were able to hold together as a family despite that, by arranging dinners and weekends and taking vacations when we could. But a lot of the credit goes to my wife, who is quite a remarkable woman. So, I mean, fortunately, as I look back on all this, to my mind, the most important thing in my life has been the relationship I have with my wife and children and then, beyond that circle would probably be with my friends and students, and beyond that would be the various things that I’ve written, and beyond that would be the major policy issues that I’ve had an effect on. But the one that’s at the core of all that set of concentric circles is that family one.

JBG: That’s really, really lovely. We talked a little bit during our last conversation, Professor Nye, about what you shared as finding a balance between the desire to know and the desire to do and the way that’s impacted the way that you’ve navigated your career that’s involved these elements of both academic and government service, and I was wondering if you would mind sharing a little bit about the way you think about that.

JN: Well, it’s true. I call it, jokingly, being torn between the temptations of omniscience and omnipotence. Obviously, I don’t have either, but when I was in academic life, I could take all the time I wanted to explore a concept and get it to the point where it was worthy of publishing in a peer-reviewed journal. When you’re in government and you’re trying to move a policy and get people to do things, you’ve got to get the paper out and get the ideas out right away. So, as I say, in academia, you always want to have an A+ paper. In government, some A+ papers, if they miss the deadline, are Fs, so, you often have to settle for a B+. If you get the B+ in the right place, you can move policy. So, there’s that, kind of, tension between omniscience and omnipotence, if you want, a trade-off.

But when I was in government, the Clinton administration, there was also the fact that when I was running the National [1:00:00] Intelligence Council, I had access to an extraordinary amount of information and, you know, it's fascinating to be on top of a pile of information like this. But then, when you’d go to a meeting in the White House, after you gave your briefing on how the situation looked and people argued about what to do, you weren’t supposed to try to weigh in on what to do. When I was in the Pentagon, I would have less time to get all the information, but I would spend my time trying to organise coalitions that could get things done. So, those are two examples, academic and government, and between intelligence and policy within government, two examples of what I call the trade-off between omniscience and omnipotence.

JBG: And so, were you back in Harvard in around 1995?

JN: Yes. Again, showing how little I’m able to predict my own future, in early 1995, my two-year leave from Harvard was up. I was working on this policy on Japan and Asia, and I thought, ‘It’s more important that I get this done than that I get back to my tenured professorship at Harvard.’ So, I wrote Harvard a letter resigning my tenured professorship and I stayed on as assistant secretary, and we were able to get that Japan initiative to succeed. Then, the question came in an awkward way: I got an inquiry – it must have been early 1995 – about whether I’d be interested in becoming dean of the Kennedy School of Government, and my first reaction was ‘No,’ for the reasons I just gave.

But then, 19 April 1995 was the Oklahoma City bombing, in which Timothy McVeigh, an anti-government extremist, bombed the Murrah building in Oklahoma City, killing 160-some civilians and thinking he was freeing the American people from government. And I thought, ‘There’s something wrong with this picture. The people I’m working with in government are working crazy long hours and really dedicated to what they’re doing. What is it that we have these views about government?’ And so, when Harvard kept persuading me to take this Kennedy School job, I thought, ‘Well, maybe I can think about that larger question if I take the Kennedy School job.’ My friend David Gergen, who was counsellor to four presidents and a wise TV commentator, said, ‘Your platform for thinking about this is going to be much better if you’re out of government than in government, because in government, you have to stay within the path. You know, your inbox controls you, not your curiosity.’ And so, I went, I took the job at Harvard and in December of 1995, about, I don’t know, a little less than a year after I’d resigned from Harvard, I wound up returning, as Dean of the Kennedy School, and one of the first things I did was start a faculty project called Visions of Governance for the Twenty-First Century, and our first book that we produced was called Why People Don’t Trust Government. We produced a number of other books along the same vein of enquiry. So, again, it’s not what I predicted but where I wound up at the end of 1995.

JBG: Wow. How long did you serve as Dean, Professor Nye?

JN: Eight and a half years.

JBG: Wow.

JN: When I took the job, I said, ‘I’ll do seven to ten,’ and it turned out to be eight and a half.

JBG: Wow. And I’m curious: you’ve had this incredible career, Professor Nye, that’s been so multifaceted, and I would love to know, when you reflect on that, what you have found to be the most rewarding and perhaps the most challenging elements of your work.

JN: Well, I think what I described earlier as the concentric circles are what’s been important in my life: you know, my family relations, and then my relations with students and friends, in which you transmit ideas outwards, and then writing, in which people are affected by your ideas, sometimes called being a public intellectual. And then, beyond that, policy implementation of actually pushing forward policies, as I did with non-proliferation under Carter, and the Japan initiative under Clinton. These are all things where I feel that I have made a difference, but they are, in terms of ranking, if you said you had to give up some of them when you wound up at the pearly gates and they said, ‘You can’t come in with all these things,’ which of this baggage you’re going to leave behind. I’d leave behind all the baggage of the outer circles if I could keep the inner circle. It’s, kind of, a corny way to put it.

JBG: No, it’s lovely.

JN: But roughly, I think the advice I would give to young people-, I mean, what I’ve tried to describe in our conversation, Jamie, is that I was not very good at predicting what I would be or do, but my advice to young people is, follow your curiosity and take new challenges, one challenge at a time. I mean, don’t think you can plan out everything, and that’s going to be particularly true for the younger Rhodes Scholars. They’re going to have to deal with extraordinary changes in technology, with artificial intelligence and the questions that are related to that. There was enormous change in technology in my lifetime. There were no computers when I was born, and nuclear weapons were created when I was eight years old, but those two things made a huge difference to the world, and I tried to spend some of my career understanding them and doing something about them. And I think that, for young people today, rather than trying to solve everything, saying, ‘All right, which of these issues that’s confronting me seizes my curiosity?’ or ‘What’s the anomaly that I can’t explain or understand? And then, if I have a chance to do something about it, whether it’s writing or policy or other forms of activism, how can I think about it?’ I think that would be the moral of the story that I tell.

JBG: That’s lovely. I would love to ask, Professor Nye, as we reach the final segment of our conversation, a few questions related to the Scholarship, the first being, what impact would you say that the Rhodes Scholarship had on your life?

JN: Oh, the Rhodes Scholarship was one of the big events of my life, obviously. So much of what I’ve described would not have happened without the Rhodes. I mean, if I had actually gone into the Marine Platoon Leadership Corps, rather than the Rhodes, I think my life would have been very, very different. So, the Rhodes provided me with a chance, at a young age of 21, to explore the world [1:10:00] and where I fit in, and to do it in the company of some very interesting people, both tutors and friends. So, I’d say that the Rhodes was one of the big events of my life.

JBG: And we just saw the 120th anniversary of the Scholarships last year, so, it’s a great time to reflect on the history of Scholarships, which is one of our hopes for the oral history project, but also a great opportunity to look ahead to the next chapter of the Rhodes Scholarships, and I would be curious to know what your hopes for the future of the Rhodes Scholarship would be.

JN: Well, I think the fact that the Rhodes Trust has broadened out to include other countries makes sense. You have to be very careful, as you do that, not to dilute the brand or the product, but on the other hand, the idea of bringing in a wider range of people to study together at Oxford, and to basically teach each other, I think the Rhodes Trust is on the right track with that. You know, what you also see with the evolution is a greater attention to professionalism. I mean, most of the American Rhodes Scholars that I’ve encountered-, I’ve gone back and taught at Oxford for probably half a dozen years or so, and most of the young Americans want to treat their studies at Oxford as a graduate degree and a step up, probably, to a profession.

When I was there, the Warden, Bill Williams, very strongly encouraged us to take undergraduate degrees, so, we wound up repeating a bachelor’s degree, and in retrospect, I think Williams was right. It threw me in the midst of college life and meeting a lot of different people. As I mentioned, I became secretary of the Junior Common Room and made a great many diverse friends, and if I’d just been focusing on getting a master’s degree to, you know, go on professionally, I think I would have missed some of that. I think that’s a lost cause now, from what I’ve discovered as I’ve talked to the American Rhodes Scholars when I’ve been teaching at Oxford. So, I think the Rhodes Trust is on the right track. I think there are some trends which are inevitable, but I think-, it’s too bad, in some ways. And going back to where we started, the fact that there are no longer sailing voyages for the Scholars to get to know each other before they arrive in Oxford, I think is a loss, but I know we’re not going to go back to scraping the paint off the Queen Elizabeth and going back on to the sailing parties.

JBG: Well, Professor Nye, I am so grateful for your time and your conversation, your participation in the oral history project, and I would love to invite if there’s anything else that you’d like to share before we close.

JN: Well, I think, you know, as we said, the Rhodes experience was crucial to my life, and I think for the young Rhodes Scholars today, focus on curiosity and integrity: explore thing that are puzzles and try to figure out why and how you can better understand them, and then try to do something about them, but always do it with a sense of, ‘I’m going to have to live with what I’ve done later, and that’s my own moral integrity.’ I think, if you do those things, you can have an interesting life and perhaps even a big one.

JBG: That’s a beautiful note to end on. Thank you so much, Professor Nye.

JN: Well, thank you, Jamie. I appreciate your questions, and it’s been fun.

JBG: Thank you. So, I will end our recording.

[file ends 1:15:04]