Born in Woodland Hills, Southern California in 1963, Jonathan Shapiro majored in history at Harvard before going to Oxford to read for an MSt in colonial history and then attending law school at UC Berkeley. After working as an attorney and Assistant US Attorney, Shapiro became an Emmy and Peabody Award winning television writer, working in particular with David E. Kelley, including as co-creator and Executive Producer of Goliath, starring Billy Bob Thornton. As well as writing for television, he has written plays, fiction and non-fiction. His latest book is How to be Abe Lincoln: Seven Steps to Leading a Legendary Life. As a result of his pro bono legal work, Shapiro has also co-founded the Public Counsel Emergency Fund for Torture Victims. This narrative is excerpted from an interview with the Rhodes Trust on 22 April, 2024.

Jonathan Shapiro

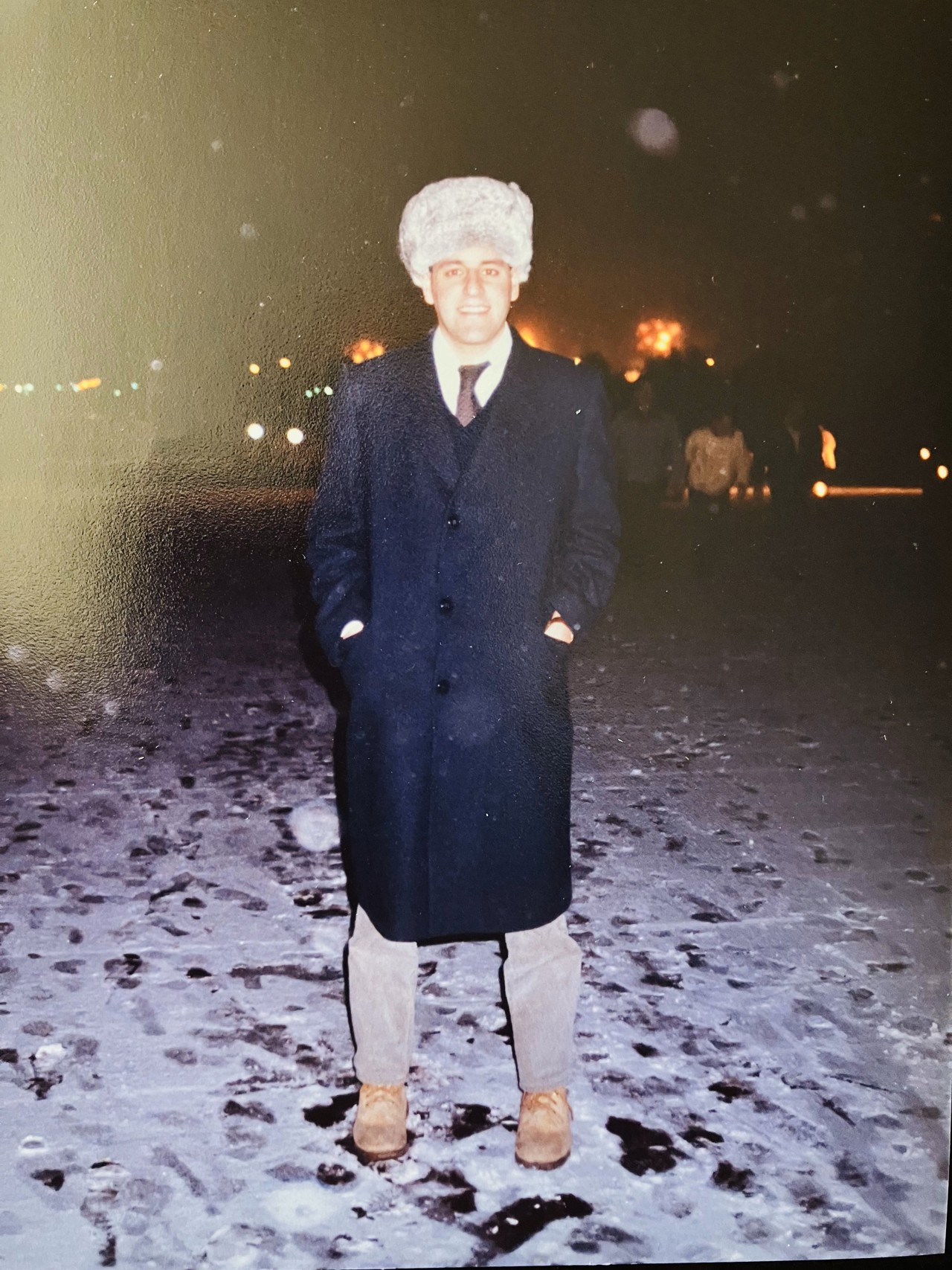

California & Oriel 1985

‘I was blessed to be a son of the Golden State’

I had loving and supportive parents and we lived in a wonderful community. School was not so good, at least to start with. I hated it and was a failure at it. I was referred to as ‘slow’ and taken out every year to be tested. But in sixth grade, I encountered a teacher, Carl Rossborough, who became the greatest influence in my life at that point. From then on, I was the class president, I ran cross-country and track and I became one of those annoying resume builders that was always thinking of the future. I was sure I was going to be a politician.

I was blessed to be a son of the Golden State. My grandfather, Abraham Mandelblatt, had come to the US in 1920 from Lublin, Poland. In 1933, he got a loan from the Lublin landsman of Fairfax in Southern California and went back to Poland to try to convince his brothers to leave, but they didn’t want to come to the US and of course, almost the whole family was destroyed during the Holocaust. I think when I was a young man the American Jewish community was still in shock over the Shoah.

I joke that the great immigrant story of America about someone coming with nothing and then making a huge fortune was not my grandfather’s story. He came to America with nothing and ended up with nothing. He went to shul every day. He was a sexton at the synagogue, and I sat on his lap and he taught me how to sing ‘Az der Rebbe’ and ‘Rebbe Elimelech’ and all those great Yiddish songs. He was definitely a man who was from centuries past, and I think that’s one of the reasons I became so interested in history.

On applying for the Rhodes Scholarship

I knew from the get-go I was going to be a history major, and I went into Harvard with advanced standing as a sophomore. It was actually at Harvard that religion began to play a bigger role in my own life. I took a wonderful course with Rabbi Cooperman and I was taught by Professor Simon Schama. I had an epiphany, that in not embracing and studying Judaism, I was denying myself a profound and important history and way of life.

At Harvard, I was still planning to go into politics, but then, lots of other things began to pull me away. I did a lot of drama and theatre and I became a Gilbert and Sullivan Player. In fact, at one of my Rhodes interviews, a member of the selection committee asked me to sing ‘He is an Englishman’ from H.M.S. Pinafore. I did it, but there was no applause afterwards and almost no mention of it, and I thought, ‘Well, that’s not going to end well.’ I got the Scholarship nonetheless, although I feel a little like I lucked into it. And if I’m honest, one of the main reasons I’d applied was because Kris Kristofferson (California & Merton 1958) was a Rhodes Scholar, and I just think he is one of the coolest human beings who ever lived. I believe in the value in heroes and I always have. And so, I wanted very much to win the Rhodes Scholarship, frankly, to try to be like my heroes.

‘I credit Oxford for everything that I became’

For good or for ill, I credit Oxford for everything that I became, because what Oxford did was give me the time and space to explore those things that had previously been drawing my attention away from a political career. It gave me a sense that art was allowable, that writing as a career is acceptable, that taking risks with your career and taking risks with your life, worthwhile risks, meaningful risks, ought to be our goal.

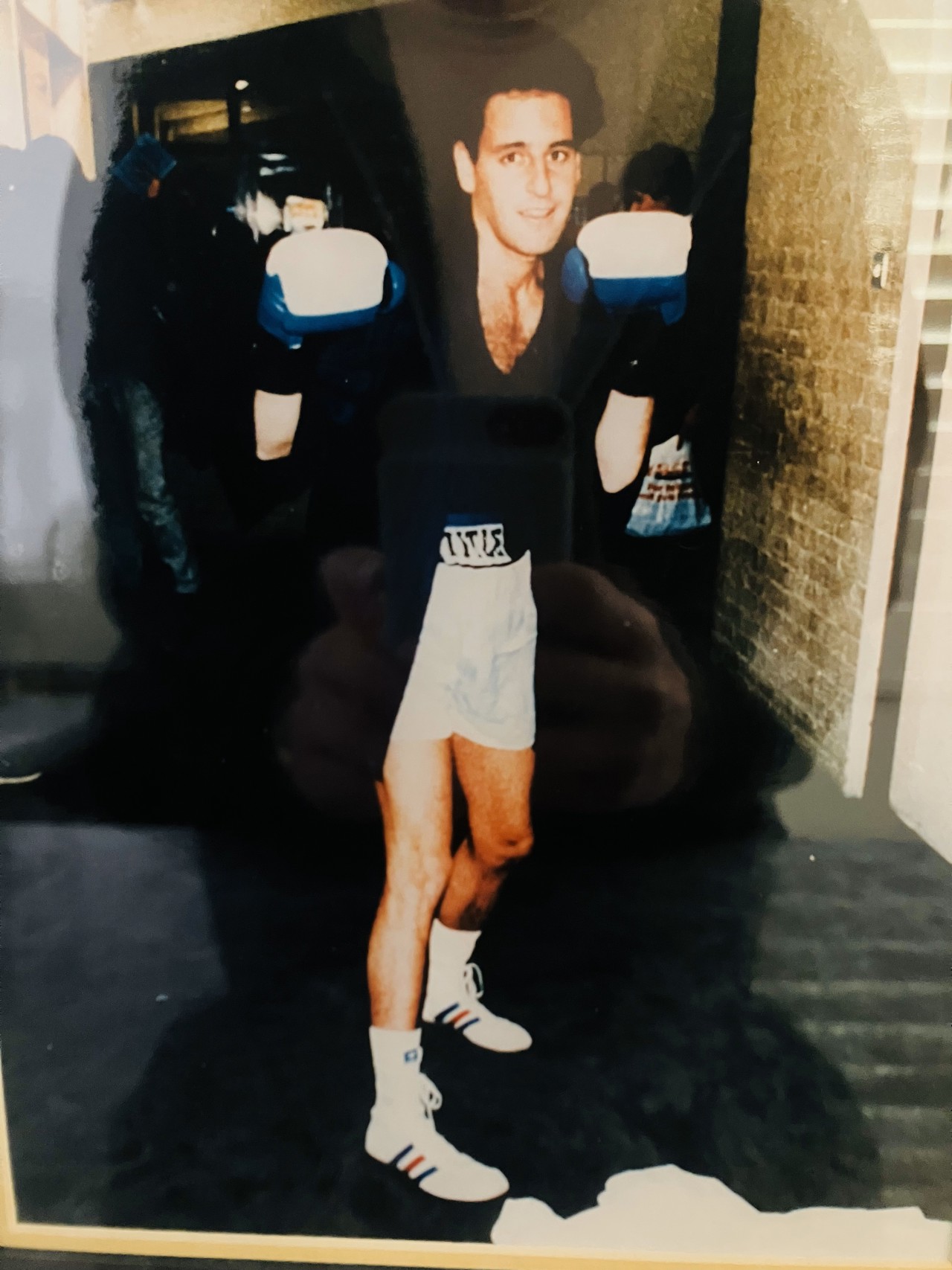

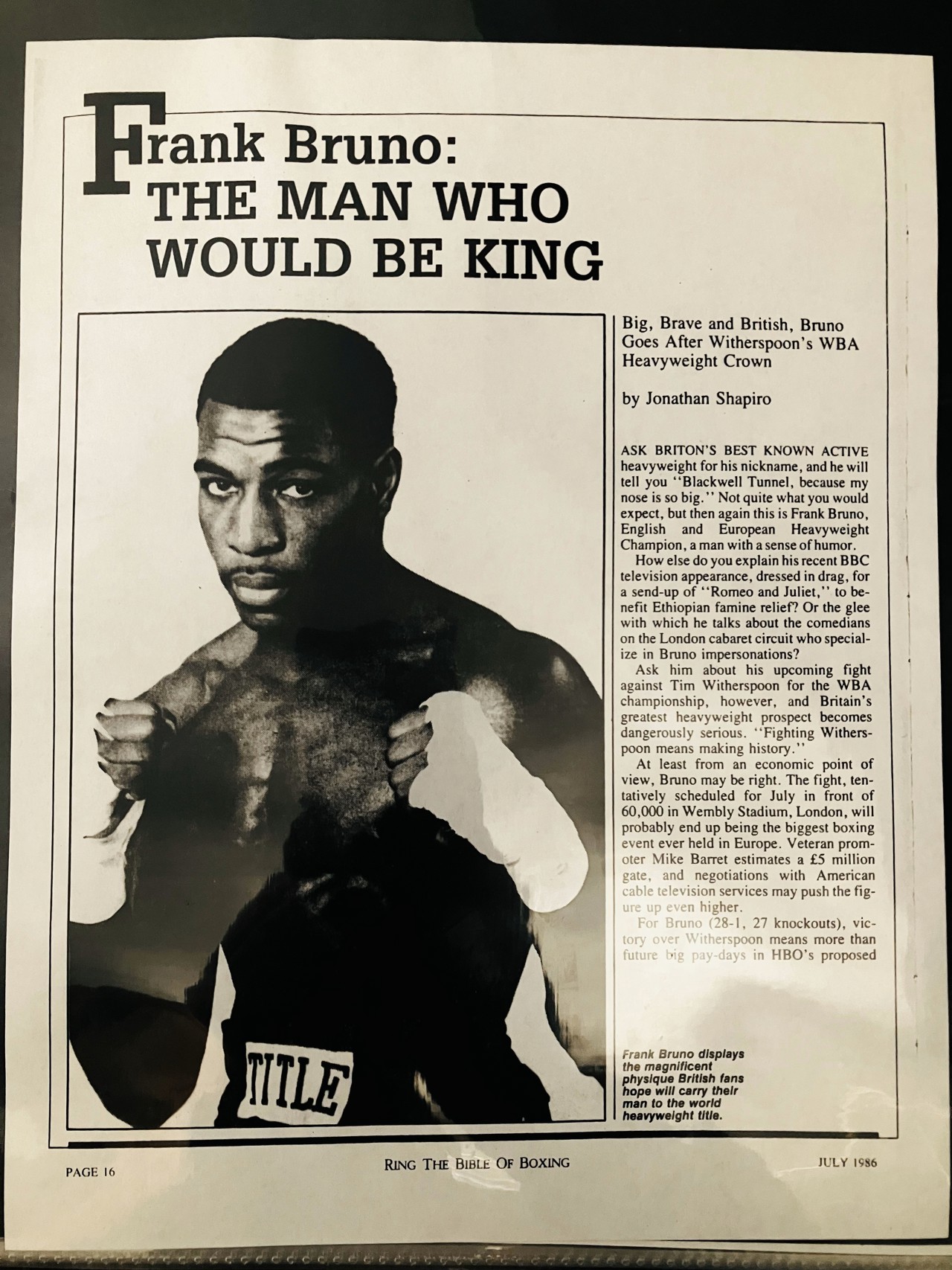

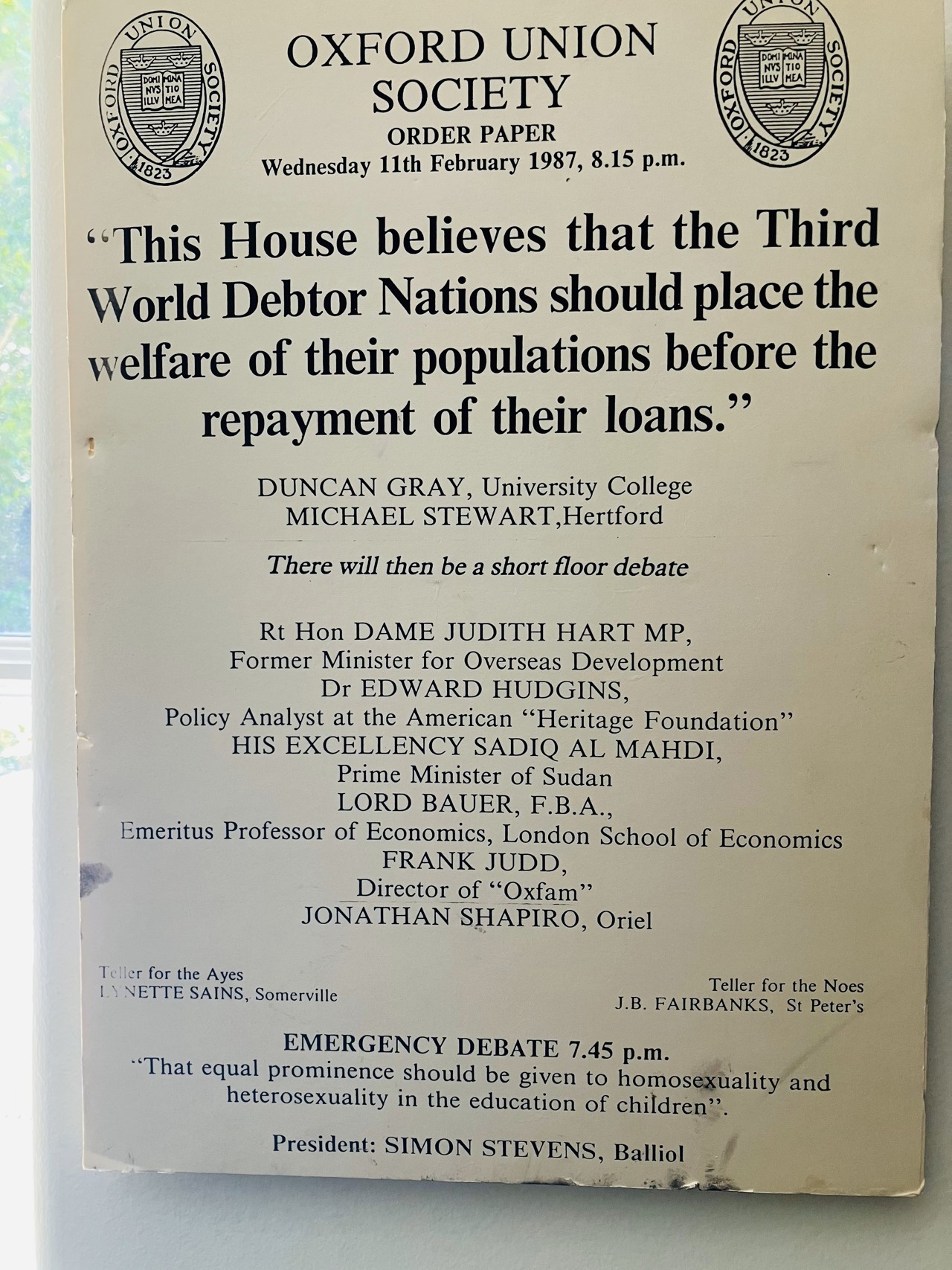

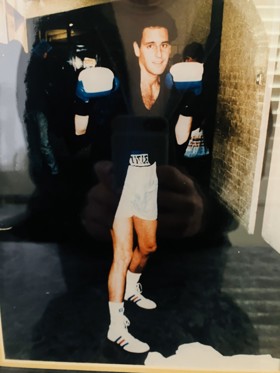

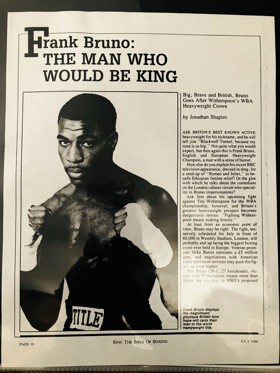

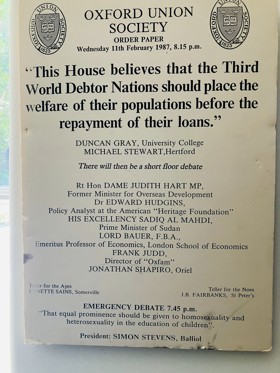

I continued to do a lot of drama at Oxford. I debated at the Oxford Union against Boris Johnson, whom people told me was going to be prime minister one day. The biggest thing was that I managed to get the editor of the boxing magazine The Ring to let me cover the fight between Frank Bruno and Gerrie Coetzee in exchange for a free ticket. Covering that fight meant that I became a contributing editor for the magazine and I ended up being a stringer for United Press International.

I was all set to be a journalist and then go into politics, but at that point, my father flew out to England from Woodland Hills and said, ‘I’ve never asked you to do anything’ – which was not true, but it was a nice beginning – ‘I’m asking you to go to law school.’ I loved my dad and I admired and respected him. As much as I groused, the fact that he was giving me this advice was not something I could ignore. And so, the compromise was, ‘Okay, I’ll show you. I’ll go to law school, but I’ll have a full-time job as a reporter.’ And that’s what I did. It was the best of both worlds, and my dad’s advice was 100% right.

‘To me, the ability to write is the most important skill’

I was fortunate enough to be hired directly out of law school, through the Honors Program, to the US Department of Justice. I had 20 trials during my first two years in DC Superior Court doing felony 2 calendars. Then I was Janet Reno’s Special Assistant during Waco, and after that, I became an Assistant US Attorney in Los Angeles. I loved it all, and I only left to become the Chief of Staff for Cruz Bustamante. Then, when Al Gore lost, that career path fell away.

I didn’t know what to do. I thought about going back to being a prosecutor, because I’d enjoyed it so much. But then, here was the chance, finally, to pursue those things that had been pulling at me for so long and really try to become a writer. The three things I’ve done with my life – being a newspaper reporter, a trial lawyer and a TV writer – are all about telling stories. What they have in common is putting pen to paper and producing something persuasive, entertaining and meaningful. To me, the ability to write is the most important skill a human being can develop.

When I went back to Rhodes House recently and spoke to the Scholars there, I said, ‘There are three things I would have guaranteed you when I left England. One, I would never get married. Two, I would never have children. And three, I would definitely run for office.’ And now, the thing I’m proudest of is my marriage and my children, and the thing I’m most relieved about is that I never ran for office. Via a circuitous route, the Rhodes Scholarship is actually the reason I met my wife, the writer and producer Betsy Borns. I was at the wedding of a fellow Rhodes Scholar and the woman sitting next to me and I were chatting. Later, she said she knew Betsy and that Betsy was the woman I was going to marry! I’m delighted to say she was right, and my collaboration with my wife is the most profound and meaningful and rewarding collaboration I have ever had.

“Take your soul seriously”

When I was younger, I would have said Rhodes deserves nothing but our condemnation. Then I got older, and I realised we have to acknowledge the good men and women do and let that good live on after them, not just their sins. I’m a liberal. I’m a lifelong Democrat. I loathe racism of all types. But I’m also a historian, and ‘Those who don’t study history are condemned to repeat it’ matters. I think all of us Rhodes Scholars have to look at Rhodes and remember, ‘But for him, I wouldn’t have gone to Oxford, and but for him, there’s no Scholarship.’

I’m so impressed with what Rhodes House is doing for Scholars these days, offering chances for people to develop the skills we need to live life. We’re all going to deal with challenges, and the best advice I can pass on is what Mel Brooks said to me when I told him I had just become a writer for television: ‘Get yourself a kepi doctor’, in other words a shrink. Look after your head or what, for want of a better term, I’ll call your soul. Take your soul seriously. Do those things that strike you as morally beautiful and that strike you in your heart as right, always; not as a career choice, and not for any other reason.

Transcript

Interviewee: Jonathan Shapiro (California & Oriel 1985) [hereafter ‘JS’]

Moderator: Jamie Byron Geller [hereafter ‘JBG’]

Date of interview: 22 April, 2024

[begins 00:05]

JBG: Okay, we are recording. This is Jamie Byron Geller on behalf of the Rhodes Trust and I’m here with Jonathan Shapiro (California & Oriel 1985) to record Jonathan’s oral history interview. Jonathan’s interview will help us to launch the first ever comprehensive Rhodes Scholar Oral History Project. So, thank you so much, Jonathan, for joining us in this project.

JS: Thank you.

JBG: Would you mind saying your full name for the recording please, Jonathan?

JS: Absolutely. It’s Jonathan Scott Shapiro (California & Oriel 1985). This is my consent to be recorded orally and on video or film or whatever this is. I have a face for radio. I might suggest radio, but anyway, you have my permission for all uses that are legal.

JBG: Wonderful. Thank you so much, Jonathan. And, where are you? We’re recording this on Zoom, but where are you joining from today?

JS: I’m joining us from overcast Southern California in my house and in my office in my house, and I say ‘my house’ advisedly. We’ve lived here 28 years and my three children refer to it as ‘Mom’s house,’ ‘Mom’s bedroom,’ etc., and I’ve just come to accept that.

JBG: And so, has Southern California been home for 28 years?

JS: I was born and bred, yes. No, I was born and raised in what we call the old country, which is Woodland Hills, which is just over the Sepulveda Pass. I’m a third-generation Angeleno and but for my time in England and in college and in various places, I’ve lived here all but 16 years of my life.

JBG: Wow. And when were you born?

JS: I was born 1963, six weeks after my maternal grandmother passed away, on the same day as my grandfather’s birthday, and President Kennedy was shot in November of that year.

JBG: Wow. Wow. And what month were you born, if you don’t mind me sharing?

JS: April.

JBG: Okay. Wonderful. And I’d love to know a little bit about your childhood growing up in Southern California.

JS: It was a wonderful childhood. My mother was a bank teller for the Bank of America for 41 years. My father was a furniture salesman whose furniture territory went from Yucaipa to the south up to Hanford to the north, which is basically the whole state of California. So, he used to be on the road quite a bit. I’m a product of the LA Unified School District. I had wonderful teachers. Frankly, we’re a much kinder America now. I know some people disagree with that, but when I was a kid I was referred to as ‘slow’ and I was every year taken out of class and tested for learning disabilities. I was a terrible student. I had the blessing or disadvantage of having an older brother, David, four and a half years older than I am, who went to the same schools and who skipped three grades because he was truly a genius – one of the youngest people ever to become a lawyer in the State of California. And it was never clear to me whether they thought I was smarter than I seemed to be or I seemed to be smarter than I was, but there was some sense that there was something decidedly wrong, and really, I hated school and was a failure at it until brain chemistry and a great teacher, sort of, met in sixth grade and a wonderful Hoosier by the name of Carl Rossborough, graduate of Purdue University, became the greatest teacher and influence in my life, and it probably helped that, you know, I had a bit of a growth spurt, so went from, sort of, the smallest, fattest kid in the class to the tallest and all that.

But from then on in, you know, it was all good. Loving, supportive parents, wonderful community. You know, I was sure that I was going to be a politician. I was always the class president and I ran cross-country and track and was one of the those annoying resume builders that was always thinking of the future, which made me unusual among Rhodes Scholars. You know, we’re generally not that way. Are you kidding? But, you know, I had all the experiences that you would want for your kid. I mean, I lied and became a Kinney Shoes salesman at 15 and was the leading salesman and was going to win the free trip to Cabo San Lucas until my manager, Mr Roach, realised I had lied about my age, and then I became a busboy and, you know, Southern California, man, it’s the best. I got my Ford Granada, drove to Zuma. I guess, from a cultural reference, the movie that most captures my youth was Fast Times at Ridgemont High, and I remember when that movie came out, and us thinking, ‘Well, this is a documentary. This is not actually a movie.” So, yes, I was a son of the Golden State, and was very blessed to be.

JBG: Wonderful. And I noticed, Jonathan, when I asked when you were born, you mentioned your grandfather in that first sentence, and I’m curious what role your extended family might have played in your upbringing.

JS: Good question. Abraham Mandelblatt, my grandfather – we shared a birthday – was from Lublin in Poland. He was a glazer by training and worked with glass. He left in 1920. What’s interesting about my grandfather is, he got a loan from the Lublin landsman of Fairfax in Southern California in 1933 and went back to Poland to try to convince his brothers to leave Poland and come to the United States because of the political situation, and he couldn’t convince them, and they said that they didn’t want to go to the United States because they felt it was too Christian a country, and of course, the family was destroyed during the Holocaust.

JBG: I’m sorry.

JS: The only two survivors were actually my great uncles, who I visited when I was at Oxford. They ended up in Belgium, and, fascinating story, they survived the camps together, three and a half years in Auschwitz. They lived within ten miles of each other and never spoke again, which is another story. So, my grandfather, Abraham Mandelblatt was a funny, charming illiterate – you know, he never learned to read or write English. I always joke that, you know, the great immigrant story about someone coming with nothing and then making a huge fortune in America was not him. He came to America with nothing and ended up with nothing. He went to shul every day. He was a sexton at the synagogue, and it’s a heck of a thing in 2024 to remember that I sat on my grandfather’s lap and he taught me how to sing Az der Rebbe and Rebbe Elimelech and all those great Yiddish songs, He was a man of the 19th, 18th century, 17th century, 16th century. I watched the moon landing holding my grandfather’s hand and, you know, I think that’s one of the reasons I became so interested in history and I got my master’s at Oxford in history. It’s a wonderful thing to think about how far the arc of the universe goes and does bend toward justice. So, anyway, the long answer to a short question. The answer to the question is that they were really important to me and I was very fortunate to know him.

JBG: Wonderful. And you mentioned your brother, David. Do you have other siblings?

JS: We just are David and Jonathan, and it’s one of the factual oddities of a Jewish family that if you have a son named Jonathan, there’s a very good chance that there’s an older boy named David, because, of course, David and Jonathan were such great friends in the Bible. If you’re the Jonathan, you have to deal with the, sort of, inferiority complex that your brother is named for the king and you’re named for a guy who gets killed in the second reel of the film. One of those things. Through therapy and a tremendous amount of pharmacology, I’ve gotten through it. Again, I’m kidding. Really, it’s not-, I don’t know why I’m doing shtick here, but it seems almost certain there won’t be many in the oral history who’ll be doing this much shtick, but you can edit it out. It’ll be fine.

JBG: I’m curious, Jonathan, about the role that religion played in your childhood.

JS: You know, Woodland Hills is an interesting place. Demographically, the Jews of Los Angeles began in East Los Angeles. My mother grew up across the street from the Breed Street Shul, which was the largest synagogue west of the Mississippi. And then, in assimilation and success, the Jews moved west and ended up in the Fairfax district where my mother went to high school. And then, with other demographic changes, some of them good and some of them bad, I must say, the Jews of Southern California then moved further west and north, which is how the San Fernando Valley became such a large contingent, and in that, you can also see the creation of Jewish congressional seats that started in East LA and then went through Fairfax and now, you know, one of my colleagues at the U.S. Attorney’s Office, Adam Schiff, is Burbank Glendale, which is interesting, because generally speaking, Jewish congressmen from my area don’t go to that area.

But, in answer to your question, Oxford played a much bigger role in my religious development than my youth. As a young man, I think the American Jewish community was still in shock over the Shoah. Religion was not an integral part of my life. We attended services and went to Hebrew school. I was bar mitzvahed. But it wasn’t until I got to Oxford and the head of my college, Oriel College, Sir Zelman Cowen, was a Jew from Australia and an attorney, and I guess it even started before that. At Harvard, I took a wonderful course with Rabbi Cooperman, ‘The Old Testament and its Interpreters,’ which was a year-long course that really gave me a blessed biblical literacy. And my professor at the time, Simon Schama, who has since written a wonderful book about the history of the Jews, we attended one High Holidays together, and I was just so struck, and I had such an epiphany, that in not embracing and studying Judaism, I was denying myself a profound and important history and way of life. And I always think it’s ironic that it is at Harvard and Oxford where those things happened.

Then, in law school in Berkeley, my favourite professor and the man who had the biggest impact on me was David Daube, whose class ‘The Old Testament and the Law of the Bible’ had a profound impact. And in fact, in my first book, Lawyers, Liars, and the Art of Storytelling, I talk about how Dalby’s religiosity and understanding of the true history of the Jewish faith and law probably solidified why it’s become so important. And of course, life, if one’s paying attention, tends to make us more spiritual. My father passed away a year ago April. He was an atheist, a proud atheist, a Christopher Hitchens-quoting atheist. He never flinched from that, and to his credit, he never held my faith against me, and Lord knows, I believe my father was the best of men, and it’s a personal thing. Joseph Conrad – and I’m going to clean it up, because he said it in an inappropriate way – said that religion is for children and God is for adults, and I suppose I adhere to that.

JBG: Thank you for sharing that.

JS: Sure.

JBG: Before we jump to your time at Harvard, one more question about your childhood: you mentioned that running was part of that, and I think you mentioned cross-country. Any other hobbies that come to mind when you think about your childhood?

JS: I was obsessed with newspapers and was a stringer for the local newspaper, covering sports. But Rhodes Scholars tend to be people who plan things, and one of the great things about turning 61 later this month-, you know, the greatest things that happen in your life, you don’t plan. So, my high school-, you know, Woodland Hills is where we used to say, ‘Below the line,’ but that’s considered inappropriate, but where a lot of production folks and, sort of, character actors-, you know, if you’re successful, you live in one place, but if you’re successful making a living but not maybe famous, you live in Woodland Hills.

So, my high school offered a shop class in television production, and we had a former local news producer who installed all the equipment, and we learned how to put on a weekly news show that was then broadcast to all of the homerooms, and I became the executive producer and anchor of that show after three years. But I learned every aspect television work back then, which was the camera, the editing, which was not how it is now, and story meetings, editorial decisions, all of it, never thinking that would prove to be the best training I ever had when I, late in life, made the transition to go from law to television. I was able to literally, my first script, sit with the set designer, sit with the production line producer, sit with the director and speak knowledgeably about lighting, camera angles, timing, story, and of all the things I did in high school that I loved and enjoyed, I would have said the TV stuff was purely just because it was a hoot, and it turned out to be tremendous training.

JBG: Great. Oh, that’s so interesting.

JS: I have to say, that was the LA Unified School District back then. It was a wonderful, wonderful education I received.

JBG: That’s great. And so, you went from high school to Harvard, is that right?

JS: I did. It was easier back then.

JBG: What did you study at Harvard?

JS: So, I knew from the get-go – because my favourite courses in high school were in history and I actually took AP history at my high school and then went to other high schools to take any AP history they offered that we didn’t offer – I was going to be a history major going in. So, I took, I guess they called it advanced standing. I went in as a sophomore and ended up getting my undergraduate and master’s degree in the four years, and I’m embarrassed to admit, because I was lucky enough that-, I don’t know that Lenny Shapiro and Cecil Rhodes had very much in common, but my father and Rhodes believed in the value of travel, and my dad had been in the Air Force and had travelled and had gotten so much out of it. So, when I was nine, we started going to England every few years, and I fell in love with history, fell in love with the culture, fell in love with the place.

And so, I declared myself a historian with a focus on 18th-century England and a minor in medieval studies and had wonderful professors like Professor Schama and John Brewer and Wallace MacCaffrey – great Elizabethan scholar – and I loved it. I mean, I loved being at Harvard. I loved being a student. I loved the people. I had never met more intelligent, funnier, attractive people in my life. And I remember rowing crew freshman year – I was a member of the lightweight crew freshman year – and I was the four seat and the guy in five seat behind me was from Long Beach, California, and we were on the Charles in November before the Tail of the Charles, and it was freezing, and it was night at, like, five in the afternoon, and him saying, ‘Why didn’t we go to UCLA?’ And I remember thinking, ‘Yeah, why was that?’ But the truth is, I, sort of, found my tribe at Harvard, and it was just about the greatest four years ever, and, you know, some of that had to do with the things I did there, but most of it, the vast majority of it, had to do with my classmates.

JBG: That’s lovely. And you mentioned that in high school you had been thinking that you might be on the path to politics, and I’m curious if that was something that was still in the realm of what you were thinking when you thought about the future when you were at Harvard.

JS: Oh, yes. Absolutely. I mean, I actually was-, this is going back a bit, but in the State of California, the State Board of Education has a student member who serves a one-year term, and I was the student member. So, I was going to Sacramento once a month, and I really got to see the inside workings of the executive branch and became very close with the Superintendent of Public Instruction at that time, who was Wilson Riles, who I write about in my book about Lincoln. He was an amazing man. He was the first African American ever elected to statewide office in California, and he was just a brilliant man, and I became one of his speechwriters while I was in college. And one of his political consultants, John Martella, was in Boston, and so, I would go over there. Yes, I stayed in politics. In the summers at Harvard, I worked as an intern in the Attorney General’s Office, John Van de Kamp, and wrote speeches for him as well.

What pulled me away a little bit was-, this is the problem of a mis-spent youth, and in fact, if one had to have a theme of my life, my dad always used to quote this Duncan Hines cake commercial, which was, ‘Bake yourself a memory,’ and I would do something maybe a little off topic for politics or off topic for law, and he would say, ‘Well, there you go again, baking yourself a memory.’ And so, I began to do theatre at Harvard and I became a Gilbert and Sullivan Player and did three shows there and I was at Kirkland House and I did the drama at Kirkland House, and I joined the Hasty Pudding Theatricals, which was still all-male then and we dressed as women and it was a full-on Broadway-type show with New York choreographers and professional directors and so on, and we performed every year, 35 performances in Cambridge, New York, and then Bermuda.

JBG: Wow.

JS: There were 16 members in the cast. I’d say a solid quarter of us ended the experience on academic probation, and I somehow didn’t, but I loved it. It was fantastic. It was proof that it’s fun to have fun, but you have to know how. And so, the amount of effort and time that went into these productions, as silly and juvenile as they were, they were really well done, and the joy of that shared experience, of getting to do something as a cast, you know, those are the relationships that I love. But I remember the last night in Bermuda on the last how, taking my makeup off and looking in the mirror and thinking, ‘Well, this is the last fun I’m ever going to have in my whole life.’ I was very dramatic. I was a very dramatic youth. But I sincerely remember thinking that I had now ended that part of my life and I was now going to be a serious rough and tough attorney for the rest of my life.

JBG: So, what inspired you to apply for the Rhodes Scholarship? When did you start thinking about that during your time at Harvard?

JS: I’m embarrassed to admit it was in high school, when I read John McPhee’s book about Bill Bradley (Missouri & Worcester 1965), A Sense of What You Are. It’s the first I’d ever heard of the Rhodes Scholarship. So, it was a thought in my mind. Because my focus was on the 18th century, I didn’t do a tremendous amount on the 19th century, but the British history courses I did do included studying Rhodes and specifically Rhodes’s use of newspaper coverage to shape his narrative, I thought was fascinating. And then, you know, I’m a Californian, and I guess every Californian knows Kris Kristofferson (California & Merton 1958) was a California Rhodes Scholar, and for those who may not know, Kris Kristofferson is the coolest human being who ever lived. Along with writing songs for Janis Joplin and Johnny Cash and others, along with Vietnam-era helicopter pilot, he was also a boxer who boxed for-, he got his Blue on the boxing team. So, you know, I’ve written a book about Abe Lincoln. I believe in the value in heroes and I always have. And so, I wanted very much to win the Rhodes Scholarship, frankly, to try to be like my heroes, which is a shallow reason for wanting to do something, but it is my heritage. I mean, we are encouraged to be like our forefathers, Abraham, Isaac and Jacob, Rachel, Leah and Sarah. And so, I say it without too much embarrassment. I actually do think, and the reason I wrote a book about Abe Lincoln, obviously, is, like Carlisle, I think there’s great value in hero worship. I’m probably wrong, but I do anyway.

JBG: And so, did you apply for the Scholarship during your senior year at Harvard?

JS: Actually, I applied during my master’s year, because my senior year was my third year, and so, my fourth year, I was a graduate student. And it’s a long shot for everybody. It’s become more of a long shot. I had the honour of coming back to Rhodes House for, I think, the second annual retreat, when the Warden was Charles Conn, and I got to speak to the Scholars then and I was so humbled by their genius and the breadth of their experiences. It was that way when I applied too, but it’s only gotten more so, and so, any old Rhodes Scholar such as myself who says, ‘Oh, I’d win it now,’ is lying.

JBG: Do you recall that moment, Jonathan, of learning that you’d been selected.

JS: I do, and a funny story about that. First of all, the first interviews were at Berkeley. So, there were two levels, and so, the first interviews were at Berkeley and I was sure I wasn’t going to be selected, for the following reason, that a member of the committee – and I can’t remember who it was – said, ‘I see you’re a Gilbert and Sullivan Player. Would you sing for us, ‘He is an Englishman.’ Now, I want you to just imagine, this is all men. These are all men of a certain age. These are all men of a certain age in suits in what has, up till that point, been a serious conversation. And now, I had to stand up and sing from H.M.S. Pinafore, ‘He is an Englishman.’ And I did it, and in fact, I had sung it on stage, which was a lot easier than singing it in front of these guys, and I thought, ‘Wow, I didn’t sound great,’ and there was no applause afterwards, and in fact, there was almost no mention of it. We then proceeded to go right back into something serious, and I thought, ‘Well, that’s not going to end well,’ but it did.

So, I got to the finals, and my problem in the finals is, they asked me the following question, ‘When you’re not reading for school, what do you read?’ And I said, ‘Well, I’m a big fan of Barbara Tuchman’s books – The Distant Mirror, The Proud Tower – and the look I got was, kind of, negative. And so, I said, ‘You know, I know she’s considered, kind of, pot boiler history, but I think there’s great value in making history as entertaining as possible. I think the medium truly is the message.’ And I did quote Marshall McLuhan, because his daughter was on the State Board of Education, so I’d studied a little bit and I understood what he meant when he said the medium is the message. And anyway, the response from the listeners was so negative that I thought I had really stepped in it. Fast forward, they announced my name. I couldn’t believe it. Six weeks later, I’m in my college dorm room at Harvard and I receive a letter from an address I don’t recognise in Cos Cob, Maine, and it’s a handwritten letter that I have framed upstairs from the great historian Barbara Tuchman, who said, ‘I’m so pleased you enjoyed my books. Congratulations on the Rhodes Scholarship. My son-in-law was on the committee.’

JBG: Wow.

JS: And the son-in-law’s name was Rosenberg, and apparently, I find out later, that when I left the room, everybody laughed, and they laughed because they decided either I’m Thomas Ripley and I knew Rosenberg was related to Tuchman and so said it to gain advantage, or I’m just an idiot who got lucky, but either way it seemed like a good reason to give me the Scholarship, and that’s all true. Sometimes, I tell these stories, and I think, ‘Is that true?’ That is really true, and I’m reminded, a great writer once said to me, ‘Stories happen to people who can tell them.’ And to be able to recognise the unlikeliness of that set of circumstances and facts and to delight in it, you know, I’m not at all ashamed of the fact that I probably lucked into it, and that answer probably had a lot to do with it.

JBG: That is a great story.

JS: True story. True story.

JBG: And so, you arrived in Oxford, and you read history. Is that right?

JS: I did, and I got a second master’s, and MSt in colonial history, which was, again, just- John Prest was my advisor, and the opportunity to study American history from the coloniser’s standpoint, point of view, was extremely helpful.

JBG: So, were you in Oxford for one year or two years?

JS: Two years, 1985 through 1987. I got approved for a third year and was going to pursue a DPhil, and then I just got to point where I thought I should maybe get started with-, I knew I was not going to be an academic. So, of course, things being the way they are, I’ve ended up teaching 11 or 12 years at various law schools. But I wanted to get back to California. I missed home.

JBG: And did you live in college both years.

JS: I did. No, actually, as a graduate student, that’s right, I lived over The Bear pub and then I lived in another apartment on Alfred Street. It’s funny, because I became the Secretary of the Middle Common Room, so I represented the graduate students, and I remember asking Sir Zelman Cowen about letting graduate students live in college more, and it was just not something they were interested in.

JBG: And what would you say defined your time in Oxford? Was it your academic studies? Did you continue running during that time? When you think back on Oxford, I’m curious what kind of experiences stand out.

JS: Well, it’s funny. For good or for ill, I credit Oxford for everything that I became, because what Oxford did was give me the time and space to explore those things that had previously been drawing my attention away from a political career. So, I acted in an illegal production of Franny and Zooey at New College that was shut down by J.D. Salinger’s attorney. I was very proud of that. I starred at the Oxford Playhouse in a production of Grease where I sang and danced, but I think primarily was hired because I had a believable American accent. You know, I debated at the Oxford Union, which was nothing if not performative, against an idiot named Boris Johnson, who people told me was going to one day be prime minister. I did a comedy debate at the Oxford Union that was broadcast on PBS, about whether the Brits were funnier than the Americans, and the British comedian Jasper Carrott and the American comedian Alan King were against one another. I was one of the student speakers and the New York Times covered it. My name was on the front page for that. So, the biggest thing was, I wanted to go see a boxing match between the British heavyweight champion Frank Bruno and the former legitimate champion Gerrie Coetzee at Wembley, and I didn’t want to pay for the ticket. And so, I wrote Nigel Collins at The Ring magazine – the Bible of boxing – and said, ‘If you get me a press pass, I’ll cover the fight for you.’ Now, I’d never covered a fight. I’d been a stringer, but-, but at any rate, the press pass came through, I covered the fight. If you go on YouTube, you can see Bruno knocking Coetzee through the ropes and you can see a hand holding Coetzee’s head up. That’s my hand.

JBG: Wow.

JS: And so, what came of that was, I became a contributing editor for The Ring while I was at Oxford, and I covered fights involving great Brits like Lloyd Honeyghan and Terry Marsh. And, you know, this was during the Barry McGuigan era, and I got to pretend to be Damon Runyon. That then led to me becoming a stringer on Bouverie Street, off Fleet Street, for United Press International. So, I smiled when you said, was my experience defined by academia? And the answer would be, ‘No.’ My experience was defined by acting foolish on stage, debating at the Union and becoming a journalist.

The highlight of my UPI experience was, in 1986, the woman who happened to cover fashion for United Press International was sick. Arthur Herman, the editor sent me as new stringer to cover the fall fashion shows in London. And I said to Herman, ‘I don’t know anything about fashion.’ And he said, ‘Well, stand next to someone who does, and take down everything they say.’ What I wrote, and then which went throughout the world, was an article that began with the lead, ‘Fall has arrived in London in a swirl of taffeta.’ And I used terms like, ‘An insouciant boudoir,’ and I made reference to an ‘Ampere’ cut, although I called it an ‘Empire cut,’ and someone had to correct me. And, you know, a press pass is a ticket to adventure, right? It’s the opportunity to bake yourself all kinds of memories. You know, I got sent to cover Comic Relief. and I got the interview and talked to Kate Bush and Lenny Henry, and I’m a Southern Californian, so I can say this without shame: it was cool. Oxford was like everything else. It was an opportunity to bake yourself a memory and do cool stuff, because I’ve always felt that that’s the whole point.

JBG: That’s really lovely.

JS: As I say it, it seems exceedingly shallow, but sadly, that’s, kind of, how we think out here.

JBG: I don’t think it’s shallow at all. I think it’s really, really interesting.

JS: You’ve very nice. You’re very sweet.

JBG: And so, previously, up to this point, you’d been thinking about politics.

JS: Right.

JBG: And as you were in oxford, is that still something that you envisioned being on the horizon for you?

JS: Yes, and I was in touch with a political consultant. I was in touch with guys like Robert Hertzberg, who was later Speaker of the California State Assembly. My mentor was a fellow named John Mockler, who has since passed away, but he was the Secretary of Education under Governor Schwarzenegger and Governor Davis, and a California legend. And yes, we were shopping for a district somewhere in the Valley with a nice Jewish population that would cotton to the name ‘Shapiro’ on the ballot, and I was already thinking that if I was going to go to law school – and I had deferred Berkeley – that the thing to do would be to be a prosecutor, because that’s always a good-, so, yes, I was thinking of nothing else, really. I was doing these other things but thinking that was where it was going to go.

JBG: Okay. And so, did you go right from Oxford to UC Berkeley?

JS: I did, except, again, I got a job full-time as a staff writer for the Recorder newspaper in San Francisco, because one of the reasons I went to Berkeley is that it was pass/fail. And so, my brother is an attorney who went to UCLA and it seemed to me that-, you know, that old joke about, ‘What do you call the guy who graduates last in medical school? You call him “Doctor”.’ It seemed to me that if I passed the bar, I’d be a lawyer, and so, I took an appalling lack of interest in my grades.

JBG: Okay.

JS: To the point where I was taking antitrust, and I turn to one of my classmates, and I say, ‘How do you spell the name of this professor?’ And the guy said, ‘My name is Professor Elhauge,’ and he spelled it for me. So, I passed. I didn’t fail anything. But it was nothing to write home about. I did get double honours for one class, however, which I’m proud of. I got double honours for Professor Daube’s course on biblical law, and a lot of good that does one. I mean, I could represent someone accused of witchcraft. I could represent someone accused of spoiling the Tabernacle. But I was very proud of that. And also, I was very proud of the fact that I got into the finals of the moot court competition and came in a nifty second. The only good thing about that is, I got the vote of Supreme Court Justice Kennedy, who was there, and lost the Ninth Circuit judges, which, sort of, foreshadowed what would happen to me as a prosecutor, but we’re getting ahead of things.

JBG: And if I recall correctly in our last conversation, Jonathan, did you mention that there were some family members who had really encouraged you to go to law school?

JS: Oh, you’re very sweet to say ‘encouraged.’ What happened was, my experiences at Oxford had so, sort of, opened my mind to the possibilities, that one could actually do what one wanted to do versus what one should do, that I got a job as a newspaper reporter, full-time, on the theory that that’s what I would do, and I would go into politics from, sort of, that angle. I actually had the idea that I’d be a sort of Anthony Lewis meets a progressive politician who having covered politics, was now going to run for office, and it seemed like a pretty good path. And it was a pretty good path, until my father flew out to England from Woodland Hills, California, taking time off the territory, to say to me, in essence – and not even in essence – this is a quote, ‘I’ve never asked you to do anything,’ which is not true, but it was a nice beginning. ‘I’m asking you to go to law school, and if you don’t go to law school, I’ll never forgive you.’ And I said, ‘Dad, you can’t do that.’ And he said, ‘No, of course I can. I just did it. I’m your father, and I don’t think the whole point of your education was to be a writer, because who can make a living as a writer?’

And, you know, my brother and I were the first people in our families on either side to go to college. You know, my mother got a scholarship to go to UCLA, but her immigrant parents said, ‘Women don’t need a college education.’ My parents were married 66 years, and they had a joyous and wonderful life. They were also two of the best read and smartest people I ever knew. So, for all my efforts as a young person to get fancy degrees and grades and scholarships, by the time I got to law school, I realised they didn’t matter at all, really. But my dad, yes, this is all true, and the truth is I loved my dad and I admired my dad and I respected my dad, and as much as I groused, the fact that he was giving me this advice was not something I could ignore. And so, the compromise was, ‘Okay, I’ll show you. I’ll go to law school, but I’ll have a full-time job as a reporter.’ And that’s what I did, and it was the best of both worlds. I would literally cover-, I covered a long-time racketeering trial where a federal district court judge, Aguilar, was being prosecuted for a conspiracy to obstruct justice, and I’d file my story, and then I’d run back to law school and take my constitutional law course or my criminal law course, and what Professor Kadish was teaching us about criminal law and procedure, I had just seen, and just asked the lawyers about it. I won the lottery as a journalist – and I say that with dark humour – to witness the execution of Robert Alton Harris, who was the first person after the Furman decision to be executed in California, and I interviewed the prosecutor who put Harris on death row. His name was Lewis Hanoian, and Hanoian was famous because he had argued before the Supreme Court on a case involving search warrants and mobile homes. When I sat down to take the bar exam, the question was about the Supreme Court decision on warrants and mobile homes, and so, I got to talk about the lawyer who argued the case, Lewis Hanoian.

So, to me, this practical experience, with the education I received, was the greatest training anybody ever had to be a lawyer, and, you know, my dad’s advice was 100% right. I loved being a lawyer. I mean, I loved it. I did it 12 years. I loved trying cases, I loved being an Assistant US Attorney. I loved working as Janet Reno’s Special Assistant during the Waco hearings. You know, the goal of being a politician got me into rooms and got me experiences that gave me training for all kinds of things. So, I was still nurturing the political bug through law school. I was fortunate enough to be hired directly out of law school, through the Honors Program, to the US Department of Justice. You know, I had 20 trials during my first two years in DC Superior Court doing felony 2 calendars, then became Reno’s assistant during Waco. Then became an Assistant US Attorney in Los Angeles, where I did organised crime cases, espionage cases. Argued in front of the Fourth Circuit, argued in front of the Ninth Circuit. I loved it.

I left after ten years to become the Chief of Staff for a fellow I didn’t know named Cruz Bustamante, who had just been elected Lieutenant Governor. This was during that period of time where Ricky Martin was on the cover of TIME magazine, because the nation had discovered Latino Americans as a political force and as a cultural force. Warren Christopher, who was at the firm I went to, suggested I work for Cruz and then leave to run for the State Assembly. We then became one of Al Gore’s co-chairs for California, and the plan was that when Gore won – I guess Gore did win – when Gore officially won – I joke – Cruz was going to be Secretary of the Interior and I was going to go to Washington as the Under Secretary of the Interior, or something like it. And then, you probably heard, Gore didn’t win, and thus dies innumerable dreams and career paths, not just mine and Cruz’s. And I was 32 years old, and we had just had twins, [50:00] Abraham and Sarah, because truly, anything you put in front of Shapiro is not going to pass, and I didn’t know what to do. I had the opportunity to go back to O’Melveny & Myers, or possibly get my old job back as a prosecutor, because I loved that job, or, you know, finally pursue those things that had been pulling at me for so long, and really try and become a writer. And as a lawyer, I reviewed books for newspapers, and I had a humour column with the Daily Journal, but, you know, 32 is old enough to decide whether you want to-, it’s maybe just about the end of the time when maybe you can make this sort of decision.

And my beloved wife, Betsy Borns Shapiro – the ‘Shapiro’ is silent – is a writer. She wrote a legendary book. If you ask a stand-up comedian about the book Comic Lives, they will have read it. It was a book she wrote in the 1980s when she was an assistant to Andy Warhol and was a contributing editor for Interview magazine, and she spent a year interviewing comics like George Carlin and a young Jerry Seinfeld and wrote this book about stand-up comedy. She then became an executive under Barry Diller, left that to be a TV writer, wrote for Roseanne for four years, wrote for Friends. I only mention this because she’s the woman who wrote ‘Smelly Cat’ and that just seems like something someone should mention. Anyway, my wife said, ‘Look, if you could sell a script and get enough points to get into the Writers Guild of America, we could get double health benefits, which will be helpful with the twins.’ And because I’m a third-generation Angeleno, I said, ‘No. TV people, show business people, are basically one step below carnys, and I have no interest in being like every other guy with a script.’ And I have to give my wife full credit. She said, ‘That’s a cop out. You’re just afraid that you can’t be a full-time writer.’ And she was right. So, I wrote a script that got to the great TV writer David E. Kelley. David E. Kelley is the only man to have ever won the Emmy for best drama and best comedy the same year.

JBG: Wow.

JS: The most prolific TV writer and the most honoured and the greatest. And we had a meeting – he’s a former attorney – married to Michelle Pfeiffer, Princeton graduate, captain of a hockey team then, and played professional hockey. Again, the coolest, right? I am driven and attracted to coolness. It was true of Miles Davis, it’s true of me, I say, shamelessly. And talked, and he said, ‘Did anything funny ever happen to you in court?’ and I gave him a story about one of my trials and he laughed, and he said, ‘Well, if you can write that and get it to me by Monday, and it’s good enough, you’re hired.’

JBG: Wow.

JS: And so, I did, and I was, and that was 24 years ago. The proudest boast I can make, the proudest boast that any TV writer can make, is that I’ve never been unemployed. I’ve created my own shows. Most of them were cancelled. A few of them were, kind of, hits. I’ve worked on other people’s hits. I’ve been a professional in a hard profession, and if you were say to me, ‘What are you proudest of professionally?’ it is that I was a good newspaper man, I had success in that, and I was a good lawyer, and there were people who would swear to that, and I was a good TV writer. And, you know, would I have preferred to have been a lights-out success in one thing? No, because I couldn’t have been. I’m just not built that way. You know, Isaiah Berlin talks about the hedgehog and the fox, and the hedgehog knows a great deal about one thing, and the fox knows a little bit about many things. It’s the only way you could describe me as a fox, but I am someone who thinks we live once and we ought to experience as much as we can in as healthy and as productive and in as loving a way as possible. And so, I don’t usually think about these things or talk about these things, but I’m not usually interviewed for an oral history. So, anyway, that’s what occurs to me.

JBG: Those are three very distinct careers, in some ways, but that supported each other in such lovely ways, and that really built on each other as you’ve navigated your career.

JS: And again, all of this comes from the fact that my eighth-grade English teacher, Joan Martin, said I was a good writer, and because I was such an avid reader, it was the first time it occurred to me that I could contribute something. And because I loved that teacher, and because she was tough, it meant something to me. And then, if you would ask me what my favourite class in college was, I would say the mandatory expository writing class, where Professor Schaller, like Joan Martin, really taught me how to write, and made me read Strunk and White, and made me understand that good writing requires the fewest number of words possible, elegantly presented. And I only wrote one thing for the college newspaper, but it was an editorial I wrote about an issue on campus, and the morning it came out, I handed in my midterm to my professor, Wallace MacCaffrey, and he said, ‘I enjoyed your editorial. I think you made some good points.’ And the idea that my professor knew who the hell I was, and having read his textbook, now, he had read my editorial, it was the greatest thing that ever happened.

So, you’re very kind in saying that these are three separate things, and they are three separate things, but what’s fundamental to them is they’re all based on writing. The best thing I did for our children is to emphasise the ability to write. You know, to me, the ability to write is the most important skill a human being can develop. You know, I sometimes used to think, ‘Well, what those three things really have in common is storytelling.’ If you’re a newspaper man, if you’re a trial lawyer, if you’re a TV writer, you’re telling stories. And that’s true, but it’s not really true. What all of those things have in common is the ability to put pen to paper and to produce something persuasive, entertaining, meaningful. And I don’t claim to be the greatest writer on Earth, not even close, but I do like to think of myself as an all-rounder. So, I’ve written books. I’ve got a play that’s currently in its seventh production out there on tour. Television. I like to say, you know, ‘You can hire me and what you get may not be a Pulitzer prize-winner, but it will be usable.’ That’s no small thing.

JBG: No. No. Speaking of books, Jonathan, would you mind sharing a little bit about that portion of your writing career, and most recently, How to be Abe Lincoln, and what inspired you to write that particular work?

JS: Well, thank you. Like all writers, I’m first and foremost a reader, and Abe Lincoln spoke eloquently of his love of books. It’s something I love, something that was encouraged. My mom has always been the kind of person who reads 100 books a year and keeps a list. So, the idea of writing a book I actually found intimidating, and didn’t do it until-, my first book came out in 2014, and it’s had a wonderful, kind of, life. The title of the book is, Lawyers, Liars and the Art of Storytelling, and it’s really a book on rhetoric, based on the Aristotelian notion that the best argument is based on the rhetorical triangle, [1:00:00] and that goes not just for newspaper articles and legal briefs, but for movie scripts and television. What’s been fun about that book is that it’s gone into several press runs, but it’s also led to me becoming a regular speaker at State Bar events, judicial events. I guess I’ve been to 30 states speaking about the book. I’ll be going up into Monterey to talk to the National Association of Appellate Justices in a month or two. And it’s been a great way to, sort of, talk about the value of rhetoric in modern society.

My second books was a novel, called Deadly Force, which is about a civil rights case based on a police beating case that I prosecuted when I was an Assistant US Attorney. It has a woman Assistant US Attorney named Lizzie Scott at the centre of it, and it’s based on a number of women I worked with. It just turned out that the women prosecutors in my office happened to be the toughest, bravest prosecutors that I ever saw, one of whom-, I was in the room when the DEA said that that they had a big continuing criminal enterprise against the Sinaloa Cartel, but they couldn’t guarantee the safety of the prosecutor handling it, and I got to see seven men, including myself, sit on our hands when the woman who ultimately did the case raised her hand. So, Lizzie Scott is based on that. Now, the book has optioned, and I only share this because it shows you something about the media landscape we’re in. I wrote that book because I tried to sell it as a TV show and the executive producer said, ‘Jeez, if there was a book like this – you know, intellectual property – it might be better.’ So, I went to write the book in order to sell the TV show. So, I wrote the book, the book was optioned, and nothing happened for ten years. Last week, Fox bought it, and as a TV series.

JBG: Wow.

JS: And I had forgotten, in the book, I describe her as being a former point guard for the University of California Berkeley’s women’s basketball team, and I talked a lot about how her personality was really represented by the woman point guard collegiate basketball player. And somebody remembered that, and as women’s sports rises, as Caitlin Clark becomes the $78 million woman with a new Nike shoe, when the women’s basketball final outpaces the men’s final by four million viewers, suddenly that character becomes relevant. So, that tickles me. And then the third book, as you mentioned, just came out in October. It’s called, How to be Abe Lincoln: Seven Steps to Leading a Legendary Life, which is the last thing my father got to read before he passed away, and I’m very proud. In fact, I sadly had to go through the book and change the present tense to the past tense, which was not much fun.

But as you see, there’s Abe Lincoln behind me. That’s been here since-, that was a college graduation present. My oldest son is Abraham. When my grandfather took out his citizenship papers, he got, in Yiddish, a pamphlet about how to be a good American, and Abe Lincoln is the second page, explaining who Abe Lincoln was. And Abe Lincoln is the famous person who I would want at any literary party. He’s the person who I consider without question the greatest American that has ever been. And the writer, lawyer, unfortunately joking person that I am, so relates to Lincoln on every level, including his struggles with depression, dark times, and I was asked if I wanted to write another book, and I, sort of, had the same experience I had when I decided to try to be a TV writer, which is, what’s keeping me from writing a book about the subject I’m most interested in? Fear. The fear of failure. And that’s a good reason, but it’s not a good enough reason not to do it, and I’ve been really thrilled with how the book has been received and, you know, it’s the biggest seller that the publisher has ever had since 1947. And yes, I’m bragging.

JBG: That’s amazing.

JS: But it’s just been great, and I hope people read it.

JBG: Great. And thank you for sharing it with the Rhodes community tomorrow.

JS: I’m a little intimidated. The gentleman who’s interviewing me is an All Souls fellow and brilliant, and I hope he’s kind.

JBG: I’m sure it will be a great conversation.

JS: I hope so.

JBG: I was wondering, Jonathan, if you would mind speaking a little bit about the pro bono work that you’ve done.

JS: Sure. You know, this is history, so I think it should be as honest as possible. I was brought to pro bono work for selfish reasons. The second TV show I created was cancelled. Show business is the business of failure. So, you know, it’s, sort of, a given that when your show premiers, you have the good news of your show premiering and you also have the likelihood it’s going to be cancelled. I think 80% of all new TV shows are cancelled before the end of the first year, which should make you feel better, but doesn’t, which leads to this wonderful anecdote, which is, you know, you spend about two years developing a show and producing it and casting it, and it’s cancelled, and it’s a really public humiliation, like losing an election or getting fired famously. And it just so happened to be the day before Yom Kippur, the holiest day of the year. I went to temple, and I thought, ‘Well, this is a blessing because I will have the comfort and the protection of my synagogue to deal with this cancellation,’ and at the most sacred moment of the service, when the sacred Torahs are passing through the congregation, the rabbi walks by me and says, ‘Oh, I’m sorry about the show. I thought the numbers were getting better.’

JBG: Oh, goodness.

JS: I mean, ‘Not even here.’ But I was done with show business. In Yiddish, we’ll say tonight, ‘Deyanu,’ ‘Enough.’ And my wife, again – you know, one should pick one’s life partner carefully-, I said I was going to go back to law, and she said, ‘You know, before you do that, why don’t you do a pro bono case? Just get your feet back into the stream of it, see how you like it.’ And so, I went to public counsel and my good friend Dan Grunfeld sent me a political asylum case for a man named Abdullah Awal Kedir, who was a communist activist who had been arrested and beaten in Addis Ababa during the city elections and had escaped and had arrived in our country and was seeking political asylum. And there was a warrant out for his arrest in Ethiopia and a very strong likelihood that he would at best, be incarcerated, and at worst, suffer torture again. He had been tortured there. And so, again, because this is history, I want everyone to know I sent the case back. I said, ‘I was looking for, like, a landlord-tenant dispute. I don’t need this kind of pressure.’ And Grunfeld said, ‘That’s exactly why I think you should take the case.’ Anyway, long story short-, it’s amazing you’re bringing this up now, because it just occurs to me that Mr Kedir came to our Passover Seder 15 years ago.

JBG: Wow.

JS: Sat next to my mom. And to tell the story of the Jews’ flight from slavery in the presence of a man whose flight from Ethiopia was the only way o avoid death, incarceration, was very meaningful to me. What shocked me – and I shouldn’t have been shocked – you have no right to a lawyer in an asylum hearing. You have a right to a lawyer in an American criminal case. You have no right to a lawyer in an immigration matter, which is truly life and death. And there are children who have been forced to represent themselves in asylum cases. Not only that, you can’t work when you’re seeking asylum without a work permit. They were very hard to get then. I think they’re impossible to get now. So, Mr Kedier had no money. So, when I needed him at a hearing, I had to give him bus fare, and when he didn’t have enough money for food, I gave him money for food. And it occurred to me, in so doing, I was potentially violating the California rules of professional conduct, which say a lawyer has to make a distinction between basically funding lawsuit and representing the lawsuit.

The good news is, we had a hearing and the government’s attorney spent two days trying to discredit, embarrass, break Kedir, a victim of torture, and we won the case. He got asylum. And I learned that there is a community of psychiatrists, psychologists, who volunteer their time pro bono to provide expert testimony that the people who have been victims of torture are telling the truth. We had doctors who were able to verify his physical wounds. But there was this need, I thought, and still think, to provide funds so that people who are legally pursuing asylum in court have the bus money to get to the hearing. And so, I created the Public Counsel Emergency Fund for Torture Victims, which raises money and makes donations to individual clients so that they can live long enough to have their day in court. That’s all. It takes no political position on immigration. It takes no position on the individual cases. It just says, if we are a nation of laws and everyone is entitled to our day in court, there is something fundamentally wrong and immoral about a process that starves someone to death before they can get to the hearing or keeps them from physically appearing. And that’s been a very satisfying process. Judy London, Laura Wytsma and I are on the board. Our work has allowed people from the Congo to pursue their asylum and win it. It allowed us not only to win an asylum case for a family from the Congo, but we also funded the air travel that got to reunite the mother with one of her children.

It’s been awesome. It’s been one of the most rewarding and enraging things I’ve ever done in my life. Rewarding because these are wonderful people who are a gift to the country, hard-working, wonderful people and people of faith in all its forms and in everything. We represented a family from Darfur. The mother and the daughter had been victims of female genital mutilation which was the basis for their seeking asylum, the fear that if they were to return to Darfur, they would be pressured to perform the same ritual on their daughter. Enraging, because, you know, I was a federal prosecutor for ten years. I never knew what it was like to go against the government and I would never be a criminal defence lawyer. The law I practised for Kirkland & Ellis while I was a TV writer is civil. But, you know, it’s a hell of a thing to live in a country of immigrants, to witness the unbelievable hypocrisy and insanity of our immigration process. The sad part of this is we did a lot of good, I think, for a small number of people. It’s a micro-giving programme, and it’s been rendered moot by the Trump administration’s policies and, I have to say, the current administration’s policies in regard to asylum. The asylum system, broken as it is, exists even less now than it did eight years ago, seven years ago, six years ago, and to me, that’s a-, in Yiddish, you would say, a ‘Shanda’, it’s a shame of our country.

JBG: Well, thank you for that work that you did, Jonathan, and thank you for sharing that.

JS: Sure.

JBG: You shared a little bit about Betsy, and I’m curious if you would like to share more about your family.

JS: Well, I have the Rhodes Scholarship to thank for meeting my wife, so I’m glad you asked that question, because I met my wife through a Rhodes classmate.

JBG: Really?

JS: Albeit in a circuitous route. As will occasionally happen, I had a brief romance with a fellow Rhodes Scholar. Can you say that? I don’t want to say anything untoward. These things happen sometimes, and we became very good friends. At any rate, I was invited to her wedding, the person next to me – whose name is Anne Hornaday. She’s now the Washington Post’s film critic – said, ‘I know the woman you’re going to marry. Her name is Betsy Borns, and she’s a TV writer in Los Angeles. And if you call her, you two will get married.’

JBG: Oh, my goodness.

JS: And I had been talking to Anne for maybe an hour. Now, again, this is history, so I have to tell the truth about myself, even when it’s unattractive. Because Anne Hornaday seemed like a very smart person, when she said, ‘If you call this woman, you’ll marry her,’ I didn’t call her. And so, about two weeks later, I was sitting in my office at the US Attorney’s office, and I was in the middle of a trial, and the phone rang, and I picked it up and the woman on the other end of the line said, ‘What kind of a coward are you?’ Except she didn’t use the word ‘Coward.’ I’m cleaning it up.

JBG: Okay.

JS: And those were the first words my future wife ever said to me. And I said, ‘Who is this?’ And she said, ‘I’m the woman you’re going to marry. Why haven’t you called?’

JBG: Okay.

JS: And I thought, ‘Wow, that’s interesting. And so, on our first date, I left my trial after a day of cross-examining unbelievably unfortunate cooperating witnesses to pick her up on the Warner Brothers lot where they were filming Roseanne, and we went to Musso & Frank, the famous eatery here in Los Angeles, and over martinis, I said to her, ‘So, you can be funny at will. You’re a comedy writer.’ And she said, ‘That’s right,’ and I said, ‘Well, be funny now,’ and she proceeded to say maybe the funniest and the filthiest thing I had ever heard in my life, and that started a relationship.’ There is an episode of Friends where Phoebe, played by Lisa Kudrow, is dating a guy named Johnny and they have a difficulty in the relationship and that mirrored – I’ll say no more about it. I’ll say no more about it. So, yes. And I have paid my wife back. Every time there is an evil corporation-, my wife is Betsy Borns. In the show Goliath, the evil defence industry corporation was Borns Industries. When I wrote on The Blacklist, the evil fracking company was Borns Fracking. And so, we play these little jokes with each other. But she is someone I me purely as result of the Rhodes Scholarship. She’s the funniest, smartest person I know and my best friend, and we have an adaptation of a British show called Vera – which is an ITV show – that we’ve sold to Amazon. We’re going to be writing that together.

JBG: Wow.

JS: She created her own show, a comedy show called All of Us, with Will Smith and Jada Pinkett Smith, and that ran for a number of years. The things we’re proudest of are our three children, Abraham, Sarah and Ezekiel. Ezekiel is showing every sign of being a writer himself. He’s a journalism major at the Ernie Pyle of Journalism at Indiana. The other thing I’m most proud of is our involvement in the Borns Jewish Stuies Program at Indiana University, which is really, I think, one of the nation’s premier centres for Jewish study and the teaching of Conservative and Reform Jewish rabbis. Betsy’s mother and father created it. Betsy had now taken it over as the head of it. She and I fund scholarships through through the Jewish Studies centre for faculty to teach Jewish ethics, Jewish law, and yes, I’m enormously proud of that. So, one of the things I talk about in the Lincoln book is that one of the ways that one becomes Lincoln is through collaboration, that you couldn’t be Abe Lincoln without being the kind of guy who could collaborate, sometimes with difficult people, like his law partner Billy Herndon, and like his many generals.

My collaboration with my life partner is the most profound and meaningful and most rewarding collaboration I have. As I mentioned, I would not be the professional writer I was without her encouragement. I wouldn’t be able to participate in the furthering of Jewish study, which is-, in my faith, to fund scholarship is a mitzvah and is expected of us as part of Tzedakah, as part of charity. It’s not a bonus. It’s something you’re supposed to do. But I wouldn’t be able to, if it wasn’t for her. It was such a joy to go back to Rhodes House with her and to stay in the drafty, horrible Rhodes House rooms pre-renovation. We had so much fun. And, you know, when I spoke to the Rhodes Scholars at the retreat, Betsy was in the audience, and I think you and I talked about this: you know, there’s a wonderful thing that’s happening with the Rhodes Scholarships and you’re a huge part of it, and it didn’t exist when I was there, and I’m so happy it exists now, which is this interest in addressing the whole Scholar. And for lack of a better word – and this is a controversial word – but the attention that’s now being paid to the soul of the Scholar. I think it’s just wonderful. And it was ironic that we had ‘Moral tutors’ at Oriel, because my moral tutor struck me as a strikingly immoral person – I say with affection – he was certainly entertaining.

But, in the last 30 years, you know, the growth of professors who have tenure for teaching happiness, the concept of emotional intelligence, the need for spirituality. To put it in more concrete terms, the fact that we’re all going to fail. We’re all going to deal with massive disappointments. We’re all going to deal with life challenges, addictions, problems, divorces, and what a wonderful thing to try to give people the skills to deal with these inevitabilities and to go right at it and do it in such a practical way. I just think it’s great. It’s the one thing that Rhodes House has done that I think everyone has got to see the value of. It’s just terrific.

JBG: Thank you. Thank you for sharing that. Jonathan, what motivates and inspires you today?

JS: Death. Death. I find that nothing focuses the mind like the knowledge of being hanged in two weeks, Samuel Johnson said. In the past 18 months, I lost my father-in-law, my dad, my law mentor and most recently, in October, my college roommate of four years. And I talk about, and I wrote about, my college roommate in the Lincoln book. His name is Jim Deyo, and when we lived together for four years at Harvard, six foot five inches, he rowed heavyweight crew, I rowed lightweight crew. He made money moving refrigerators. He was a giant, a gentle giant, and a religious person. We would have endless discussions. And he was devout, went to church every day, and you can imagine how much I learned from him in those four years. I’ll tell you how competitive Harvard is. Ten years later, Jim had become an Orthodox rabbi. Converted, became an Orthodox rabbi, thus proving that my college roommate turned out to be a better Jew than I am. That’s how competitive Harvard is. And Jim and I studied Talmud together. Jim attempted to improve my Hebrew, which didn’t work. Jim was at my wedding. Jim was at the blessings of my children.

And I was looking forward to growing old with Jim, because, you know, he stayed with my parents in the summers, and he’s a brother. And when 7 October happened – he lives in Jerusalem with his wife and with his daughter – Jim got very involved in the nation’s preparation and in also trying to reach out to the victims of the attack. And perhaps it was the stress, but he dropped dead of a heart attack the week after. And so, you asked me what motivates me. What motivates me is the gratitude one feels for being alive, and to still have time to make the most out of our lives. It’s the gratitude I felt when I won the Rhodes Scholarship. I couldn’t believe I’d been so lucky. It was the gratitude I felt when I got to go to college. I may not have been born with many skills, but I was born with the skill of appreciation, a deep and profound appreciation. And what happens in life, I didn’t know as a Rhodes Scholar.

As a matter of fact, if you had asked me, when I was graduating, and I think I actually said this with the Rhodes Scholars when I spoke to them, I said. ‘There are three things I would have guaranteed you when I left England, when I left the Scholarship. One is, I would never get married. Two, I would never have children. And three, I would definitely run for office.’ And the thing I’m proudest of is my marriage and my children, and the thing I’m most relieved about is that I never ran for office. And so, gratitude and humility, two things-, I had gratitude. I didn’t have a lot of humility, but gratitude and humility are my guiding principles. Lincoln said people are as happy as they decide to be. I think that’s 100% true. As someone who has struggled, like we all struggle, with things, in my darkest times, I’ve been blessed with enough belief in God and appreciation for what I’ve been given to not give up. And what happens in life is, if you’re lucky enough to have children, which is not-, [1:30:00] you know, children are not necessary, but if you have them, they’re essential. I have three children who are smarter, kinder, purer and better than I ever was, certainly at their age or now, and they teach me so much. My oldest son is on the autism scale. I write about him in my book. He’s the most Lincolnesque person I ever met. His childhood was brutal with the teasing and so forth. You know, he graduated with honours from Indiana University. He won the Senior Leadership award for having created the Neurodiversity Coalition at Indiana University.

JBG: Wow.

JS: He did Teach For America. Now he’s applying to law school.

JBG: Amazing.

JS: But there’s not an ounce of anger or bitterness. He’s as sweet as my father was, and that’s true of all my kids. It’s not true of their father. So, what motivates me is to try to be worthy of this life I have and to try to be worthy of my children and of my wife and that’s plenty of motivation. I find that to be very strong motivation.

JBG: That’s really lovely. I would love, Jonathan, before we close, to ask you a few questions related to your Rhodes and Oxford experience.

JS: Yes.

JBG: The first being – and you spoke to this a little bit -but what impact do you feel the Scholarship had on your life?

JS: It changed the direction of it entirely, but not immediately or all at once. My education’s greatest gift to me was teaching me how to learn and instilling in me a crazy desire to know what I don’t know and to pursue what I think is interesting, without reference to what I should be studying or what I think I should be doing. Oxford gave me freedom. It gave me a sense of legitimacy. It gave me a sense that art is allowable, that writing as a career is acceptable, that taking risks with your career and taking risks with your life, worthwhile risks, meaningful risks, ought to our goal, is the point, is why we’re on Earth. It’s not to be avoided, it’s to be embraced. Oxford taught me that this great big beautiful world is filled with endless numbers of smarter, more talented people, and there’s room enough for all of us. And as I say this, none of this is how I felt when I was in-, none of this is how I behaved. You know, I was not motivated-, I was motivated by a desire for credentials and success. Other people’s success sometimes felt like a threat to me. If I wasn’t number one, I resented it. Oxford really did, sort of, teach me-, Oxford gave me two years to say, ‘Just be what you want to be, do what you want to do, live the way you want to live. Dream. Dream an existence into reality, pursue a god of your own understanding.’ You know, these are all things that were introduced to me as concepts at Oxford, without question, and they have made all the difference. Oxford showed me a path I didn’t even know existed. I would never have had this life if it hadn’t been for Oxford.

JBG: Wonderful. And we are at an interesting and exciting and important moment, I think, for the Scholarships. We just marked the 120th anniversary this past summer and are thinking about the next chapter of the Scholarships. And so, I would love to know what your hopes are for the future of the Rhodes Scholarship.

JS: I hope we embrace the traditions and the histories that I feel risk being ignored because they’re challenging. And I begin, controversially, with, I hope we reach some kind of understanding of the founder that allows us to honour his generosity and the spirit of that generosity and the spirit of what his intention was, even as we understand the context of his crimes. Well, let me put it another way. When I was a federal prosecutor, I really had a hatred of the defendant, because in committing a crime, the defendant had deprived someone, or some societal aspect, of their civil rights. To me, the worst violation of civil rights is to commit a crime against someone, and Rhodes committed crimes. When I was younger, I would have said Rhodes deserves nothing but our condemnation. Then I had kids. Then I got older. Then I realised, life is not so black and white and that we have to acknowledge the good men and women do and let that good also live on after them, not just their sins, their crimes.

I’m bothered that my college, Oriel College, considered taking down the Rhodes statue. I’m a liberal. I am a lifelong Democrat. I loathe racism of all types. But I’m also a historian, and ‘Those who don’t study history are condemned to repeat it’ matters, and it is hard to look at Rhodes and remember, ‘But for him, I don’t go to Oxford, and but for him, there’s no Scholarship.’ I think decency, if nothing else, demands that the Scholarship confronts the good Rhodes did as well as the bad. And before anyone takes that out of context and says, ‘Oh, well, you’re arguing to embrace the imperial, racist Rhodes,’ no, not at all. I think the much more honest and difficult thing to do is to understand the imperialist, racist, criminal Rhodes in the context of the very real good he did for every one of us who is a Scholar, and it would be nothing short of hypocrisy to bury Rhodes, and to ignore Rhodes, and still take the Scholarship. If we are to judge Rhodes as evil because of what he did in the realm of racism and imperialism, then shame on all of us for taking the Scholarship. I hope, and not only is this my hope, I think it’s a necessity, as Scholars, as students, as people who believe in the morality of truth and fact, we’ve got to balance the evil Rhodes did with the good that we have benefited from. And I’ve never talked about this, but it’s always struck me as one of the great challenges of the Scholarship itself and the Scholars’ community. You know, in my faith, we accept that King David sent Uriah to be murdered so that King David could take Bathsheba, and that is an unforgiveable sin, it is an unforgiveable crime, and yet, King David is our hero. In my faith, and I believe in others’ faith too, we’ve got to be able to hold on to two different ideas at the same time, and I was disappointed the Rhodes community didn’t challenge the wholescale condemnation of Rhodes without even acknowledging that our community wouldn’t exist without him. [1:40:00]

JBG: Thank you. Thank you for sharing that.

JS: Sure.

JBG: Jonathan, I’m curious if you would have any words of wisdom or advice that you would offer to current or future Rhodes Scholars.