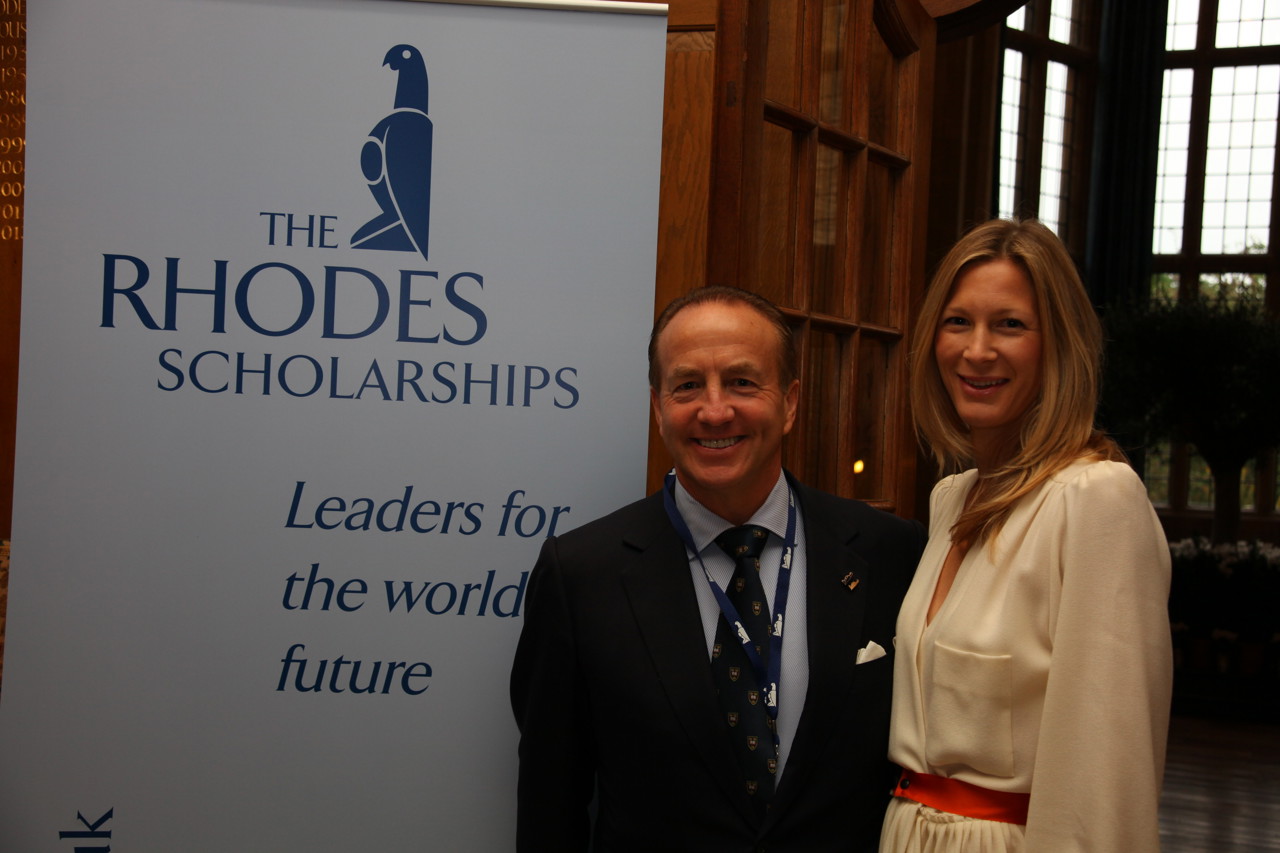

Born in Niagara Falls in 1958, John McCall MacBain studied at McGill University before going to Oxford to read for a second undergraduate degree in law. From Oxford, he went to Harvard Business School. After buying Auto Hebdo magazine in Montreal, Canada, McCall MacBain formed Trader Classified Media, the world’s leading classified advertising company. In 2007, John and Marcy McCall MacBain founded the McCall MacBain Foundation which has made philanthropic grants of approximately $500 million across the areas of education and scholarships, climate change and the environment, and youth mental health. In 2013, McCall MacBain donated $120 million to the Rhodes Trust, becoming the one of the Trust’s Second Century Founders and allowing the Trust to fund the Scholarships in perpetuity while also catalysing significant expansion of the Scholarships numbers and global reach. This narrative is excerpted from an interview with the Rhodes Trust on 4 September 2024.

John McCall MacBain

Québec & Wadham 1980

‘Teachers are super important’

I grew up in Niagara Falls where my father was a small-town lawyer. He was the crown prosecutor for the area and knew all the undercover drug officers. Once a year, he would invite them to a party, and the neighbours would call the police when they saw all these undercover officers who looked so terrible! Niagara Falls was also where I went through the Canadian public school system. I was a good student, and I especially loved geography. My grade 7 geography teacher got me really interested in travel and understanding the world and in grade 12, a group of us raised money and went on a trip to Moscow and what was then Leningrad. That changed my life and gave me a more open mind, because I saw there were such great people around the world.

I was a bit of a tough guy, and into wrestling. When I got into a fight, it was another great teacher who said, ‘You know, you’ve got to clean up your act.’ From that day on, I didn’t get into a fight. I think teachers are so important in the world and undervalued. In some of the scholarships we’ve given, we’ve had students go back to their schools and make a special presentation to teachers who transformed their lives.

My dream in life was to become a swimming instructor and when I was 17, I got my swimming instructor’s certificate and was hired. Life was great. But then, I won the Spanish contest, and when I asked the City of Niagara Falls if I could take the first week off to go to Ottawa for the next round of the contest, they said, ‘No, you’re fired.’ I was devastated, but actually, that pretty much started my entrepreneurial career. I started a competitor business by going around to people saying, ‘Can I use your pool to teach kids for free? And I’ll charge the other neighbours to come in.’ That business made up the shortfall in my scholarship to McGill and paid my way through university.

On applying for the Rhodes Scholarship

I loved McGill, and I became President of the McGill Students’ Society. That actually grew out of another failure, after I won the Southern Ontario wrestling championships but then lost in the All-Ontario contest. I stopped wrestling, and because I’d done student politics and been president of my high school, I started getting involved at McGill too, running welcome week and the winter carnival. For me, it was more about service than the political or ideological side. I liked organising things and leading people.

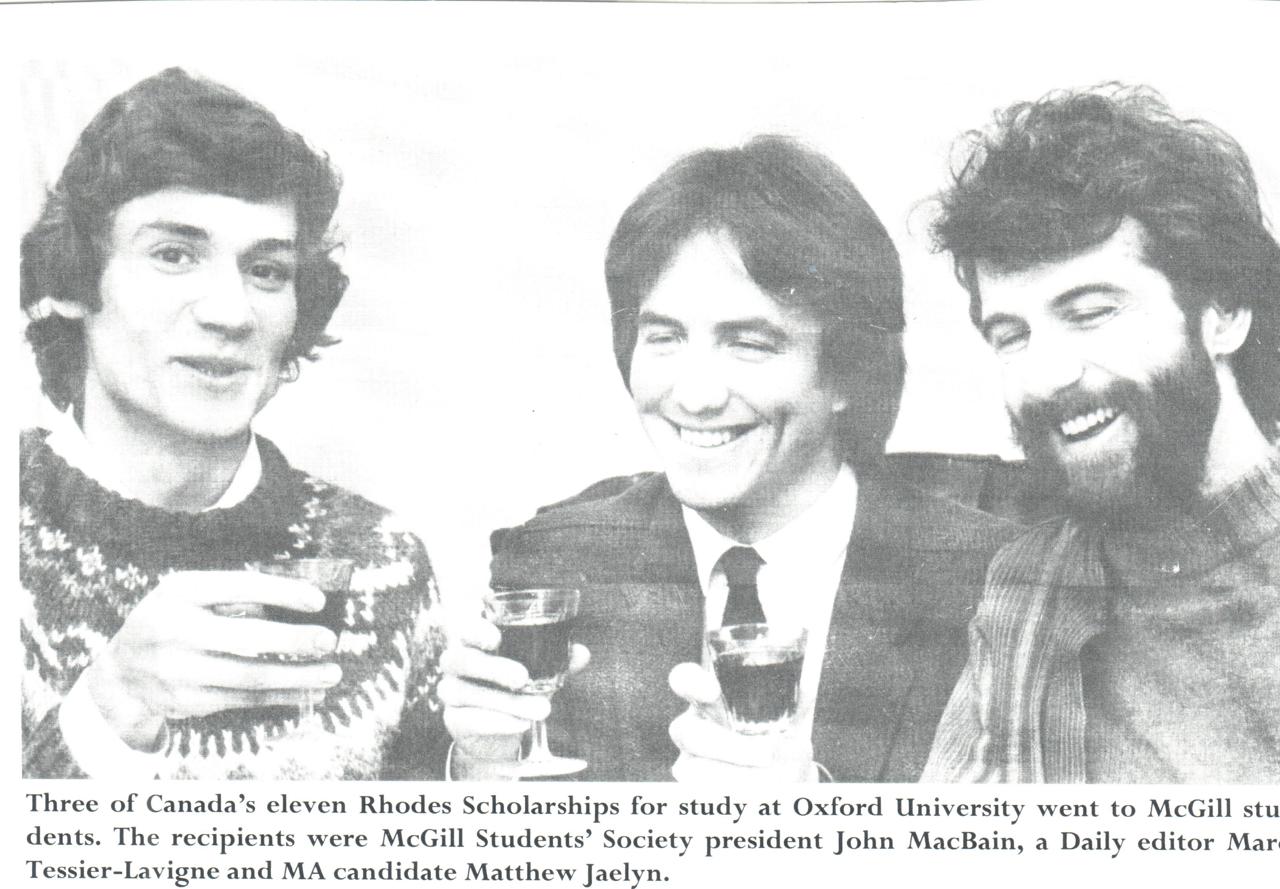

It was the then Principal of McGill, David Johnston, who later became Governor of Canada, who noticed me and said, ‘John, you know, you should apply for this scholarship called the Rhodes Scholarship.’ I didn’t know anything about it, but I applied. I remember the Scholarship interview very well. The committee asked about my thesis, which was on leadership, and we also talked about Canada. The other two Scholars who were selected in my year were Marc Tessier-Lavigne (Québec & New College 1980) who went on to become President of Stanford and Matthew Jocelyn (Maritimes & Lady Margaret Hall 1980), who is a playwright. I like the fact that the Scholarship could go to three such very different kinds of leaders in their individual fields.

‘Oxford taught me how to think’

I sailed over to England from New York with my fellow American and Canadian Rhodes Scholars and I still have friends today I met on that boat. When I look back on my time in Oxford, what I remember is studying, but also travelling and being with college friends, as well as getting involved in using my organisational skills in all kinds of ways. That started the moment we got off the boat, when it became clear that the arrangements for our luggage were in chaos! It carried on through my work as co-captain of the ice hockey team, organising their European trip, and friends and I travelled together to Europe too. I really enjoyed that.

At McGill, I had majored in economics, but at Oxford, I decided to study law. My father was the most open-minded man ever, but the one thing he said was, ‘Don’t take a law degree.’ I didn’t become a lawyer, but in fact, I did find the law I learned at Oxford very useful. I still use it every day in our philanthropic and business work. I say that McGill taught me how to lead, Oxford taught me how to think, and Harvard taught me how to manage.

‘I thought, “Somebody has got to stand up and do something”’

I went to Harvard Business School directly after Oxford. From there, I worked for a company in Montreal and then took the big step to becoming a full-time entrepreneur. I realised that classified ad papers were smaller than a daily newspaper but had 100% of ads, and I just thought that was an interesting business. I started my career in Auto Trader, and we went on to become the world leader in classified advertising. We were in 23 countries, with about 7000 employees across the world.

In 2006, I sold the company, and in 2007, my wife Marcy and I decided to become philanthropists, and we started the McCall MacBain Foundation. A good philanthropic gift is about taking a problem that you have a chance of success solving and where your cost for success is also reasonable. That’s one of the reasons we’ve done so much in scholarships. Also, I’m a Rhodes Scholar and I’d been a scholar at McGill and at Harvard. So, I was the result of scholarships.

When the Rhodes Trust got in touch with me to ask if I would like to join the Board of Trustees, I learned that the Trust had got into some problems. I thought, ‘Somebody has got to stand up and do something, or this scholarship is going to go down.’ It was clear that the Trust needed a lot, not a little. So, we made our largest gift at the time, 75 million pounds, to the Rhodes Trust. The aim was both to help and to encourage others to help. Alongside the gift itself, we also looked to successful educational fundraisers like Princeton, and we began to grow the idea of class leaders. That’s been so important, for fundraising and also for communications and building the Rhodes community. For me, my involvement with the Rhodes Trust is a real example of what entrepreneurship is about: ‘When in doubt, act.’

I was chairman of the building committee for the renovation of Rhodes House, and we’re especially proud of what we did there. For so long, Rhodes House had been almost like a mausoleum. Now, we’ve opened it up, for the Scholars in Residence, for Alumni, and for the community too. We’ve kept the House’s old, traditional and beautiful architectural structure, but we’ve added modernity and some incredibly thoughtful space utilisation. One of my favourite parts of the renovation is the glass pavilion, which was an idea we took from I.M. Pei, the architect of the glass pyramid at the Louvre. It’s this light, beautiful spot for Scholars to use, and open to the gardens, making them more part of the community.

‘You never know when you had a good day’

I’m definitely a risk-taker, and when I meet and mentor Rhodes Scholars, I encourage them to take more risks. The Rhodes Scholarship gives you a cushion to fall back on, so you can afford to do the thing that other people don’t do. Also, think more about what you like than what you’re good at. Other people will tell you what you’re good at, but nobody else can tell you what you like. If you follow your passion and take risks, you can really make things happen.

Alongside that, I guess my biggest piece of advice, which I always share with the Scholars I’m mentoring, is this: you never know when you had a good day. It’s happened to me so many times. When I was fired from the City of Niagara Falls as a swimming instructor? That was a horrible day. That was also the best day of my life, because it forced me to start my first company and it set me on the path to entrepreneurship. So, every time something goes bad, learn from it, and learn how to get out of it, and in learning how you get out of it, you might find something better.

Transcript

Interviewee: John McCall MacBain (Québec & Wadham 1980) [hereafter ‘JMM’]

Moderator: Rodolfo Lara Torres [hereafter ‘RLT’]

Date of interview: 04/09/2024

[file begins 00:04]

RLT: Great. Hi, John.

JMM: Hi.

RLT: A pleasure to be with you for our oral history project.

JMM: Thank you.

RLT: I just wanted to ask you, what is your full name?

JMM: My full name is John Howard McCall MacBain. When I was a Rhodes Scholar, I was actually John Howard MacBain. But my wife, Marcy McCall, and I got married. There were three daughters in the family, so, I thought, if we could keep that name going-, So, I changed my name, actually, to McCall MacBain. So, I have Marcy’s last name and my last name together.

RLT: That’s beautiful. Thank you. And do I have permission to record this interview?

JMM: You have permission to record this interview. Thank you.

RLT: Perfect. Thank you so much. So, we’ll start from the beginning, basically, and if you can, tell us a little bit about where and when you were born and where did you family and ancestors come from originally – I sense a little bit of Ireland or Scotland there – and how was your family life and community life in the place you grew up in?

JMM: So, I was born in Niagara Falls, Canada, about three miles, say four kilometres from the Falls, and my parents-, my father was from New Glasgow, Nova Scotia, [cannot decipher 1:17. Could be ‘On the basis of’ or ‘Based in’?] Scottish heritage from near the area of Moray and Tomatin, I guess, in Scotland. My mother was Viola Rachel Kenney, and she was no relation to the famous Kennedys, but she was a Kennedy. So, some Scottish but also some Irish, maybe a little bit of English background there. And she was from St. Mary’s, Ontario. And they met, and my dad moved up to Niagara Falls. He was a small town lawyer in Niagara Falls. And I went to public school there, to Canadian public school, government school, I guess you’d call it, to A.N. Myer Secondary School. And then at the end of that and just when I went to university, my father then became a member of Parliament in Canada for one term, the last term of Pierre Trudeau. He was a member of Parliament for Niagara Falls.

But we were a small town family, you know, just normal income, small town lawyer who interesting work in real estate. He was actually the crown prosecutor for the area, which is an appointed position. So, he ended up doing all the drug cases, so I knew all the undercover RCMP drug officers. We used to have them over for a party once a year and the neighbours would call the police, because they thought-, these people were all undercover. They looked, like, terrible. So, that is my family background. It was, you know, a good, stable family. My mom and dad were together and I had one sister who was adopted when I was five years old. And so, that’s the background in Niagara. And I was actually a wrestler at A.N. Myer School. I did that until grade 11. Then I got involved in student politics, which continued on. When I left Niagara Falls in 1977 to 1980, I went to McGill University in Montreal and studied economics and lived in Montreal, improved my French, and also, I was the president of the McGill Students’ my last year.

RLT: May I interrupt there? Because you were president of the Students’ Society at McGill, but how was school for you in elementary, middle and high school in Canada, and what were your hobbies, your interests, like there?

JMM: Yes, it’s interesting. Good question. So, I guess starting more in in high schools, my interests were-, I was a good student, especially in history and English, and pretty good in math, and I loved geography, and I think geography has had a big influence on my life. Two little things from my high school: one is that my grade 7 geography teacher really got me interested in travel and understanding the world. So, I’m quite good at geography and like geography and obviously important for work now in our foundation, through climate change. And secondly, in grade 12, we raised money and actually, we had Russian history in grade 12, and I actually went, when it was the USSR, to Moscow and Leningrad at the time. And at my little public high school, we went there for a ten-day trip, and it, sort of, changed my life, in that I, sort of, realised that, you know, there are nice people in every country. We got to know Russia a little bit, how beautiful some of the things were, and it sort of gave me a more open mind to the world as opposed to, you know, being in this small town and Canada. I saw there were great people around the world.

Our Russian trip there kept in the back of my mind and when we were in business, from 1996 to 2006, we expanded our classified advertising business into Russia. Actually, we were the largest publisher in Russia from 1996 to 2006. We sold and then, as everybody knows from history, Russia had some problems, starting in 2011, I guess with Ukraine and Crimea, but we were out before, by then. But, you know, during that time, I think we were very helpful in moving Russia from a communist to a free-market society where we had classified advertising papers, which, for free, gave ads to everyone to allow them to exchange goods. So, I think that looking back, ‘So, why were you comfortable having this business in Russia?’ ‘Well, because I went there as a kid.’ So, that’s interesting.

And so, my third interest was swimming. I was a good swimmer. My dream in life was to become a swimming instructor and work for the City of Niagara Falls. Every summer, when I came home from university, I would get this job and it would be a really good job. And so, when I was 17, I got my swimming instructor’s certificate in March and in April, I was hired as a City of Niagara Falls swimming instructor. Life was great. And unfortunately what happened was, I won the Spanish contest, actually, and had to go to Ottawa for the first week of swimming. So, I called up the City of Niagara Falls and I said, ‘Look, you know, I can’t make the first week, but there’s Harry and Sally and Jerry and two others in my class who haven’t got a job yet. Why don’t you hire them for that week and then I’ll work the other seven weeks?’ And they said, ‘No, no, you’re fired.’

So, that, sort of, started my entrepreneurial career, and what I did was, I started a competitor in the City of Niagara Falls by going around to people’s pools who had backyard pools and I said, ‘Look, can I use your pool to teach your kids for free? And I’ll charge the other neighbours to come in,’ and I started a business called The Swim School, and that actually paid my way through-, I had a scholarship at McGill, but the other expenses I had were paid by my little swimming company, which became fairly large. I had about ten employees and we had about 20 pools and it became a big little business. This is all because I was fired from my first job, which was my dream job. So, that’s, sort of, been a bit of my history. My history is a bit-, you know, there’s been something that seems like a failure, but it turns out very well. So, it seemed like the worst day of my life when I was fired from the job I dreamed of having, but of course, it turned out very well, because it made me look into the Swim School.

So, those were my major interests at the time. And then, I guess, student politics. So, the last one: when I was in grade 11, I won Southern Ontario wrestling and I went to the all-Ontarios. I lost to the guy who ended up winning the Commonwealth gold medal, and so, I said, ‘Look, I’m not going to be a good wrestler.’ So, I stopped wrestling. I did student politics in grade 12 and 13, was president of my high school, and that got me interested in student politics at McGill, where I ran the welcome week and then ran the winter carnival and then eventually became president of McGill, and then the principal of McGill, David Johnston, who later became Governor of Canada, said to me, ‘John, you know, should apply for this scholarship called the Rhodes Scholarship.’ I didn’t know anything about it. So, I applied and then became a Rhodes Scholar and went to Oxford. So, that’s, sort of, where it comes from.

RLT: That’s quite a journey. Were there any subjects, both in your earlier education and then at McGill, that were most interesting to you, and any teachers or professors at that time that played a big role in your life?

JMM: Yes. I think teachers are super important in the world and I think they’re undervalued. And I went back, actually, and decided I’d do it for myself-, and then, in some of the scholarships we’ve had students go and choose the teachers they really like and give them an award and do a presentation in front of their school to try to encourage teachers, but also to encourage other students that, you know, they can do well and get a scholarship. So, I went back to my elementary school, my senior public school and my high school. In my elementary school, I chose Mr Romanovich, who was our grade 5 teacher. And, as you heard earlier, I was a wrestler, so I was a bit of a tough guy. I got in a big fight at school. And I’ll never forget the day he turned to me and he said, ‘You know, you’ve got to clean up your act.’ And I did. From that day on, I didn’t get into a fight. And he, sort of, turned me around a bit in Grade 5. So, I remember Mr Romanovich and I actually went back to give an award at the school and say, you know, ‘Teachers I remember,’ I circled Mr Romanovich, and he wrote me back a note once, saying, you know, that ‘I’ve retired now, but every day, I look back on my career, I’m so glad I became a teacher.’

And we need more teachers to think that way and I think we as successful students from those teachers want to encourage that. So, we encouraged Mr Romanovich. And then, as I mentioned earlier, there was the grade 7 geography teacher, Mr Weibrau [guess 9:06], you know, how he changed my life, got us to look at the world and geography and understanding different cultures, different areas, different physical characteristics. It really interested me and that was, sort of, a turning point in my life as well. So, I recognised him. And then, my grade 13 second English teacher at the time, Mrs Yao [guess 9:24] turned out to be a world-class teacher and went on to be one of the famous teachers that still helps education organisation around the world. But earlier in her career, she was our grade 13 second English teacher, and I really enjoyed that, and I wrote a work on T.S. Eliot, and I still used some of his phrases: ‘This is the way the world ends / Not with a bang but with a whimper.’ Things like that. And I think that, sort of, got me a little more interested in poetry, and also interested in some of the great works of the 19th and 20th centuries.

So, those are the three I look at. And when I look through my university, at McGill, probably the I remember more is student politics, getting involved in the [10:00] school and the administration. When I was at Oxford, I had a great professor named Professor Hackney, who taught us trust law and land law. I especially appreciated the trust law and learned a lot from that. So, he was a big influence on me. And then at Harvard Business School, it was probably my marketing teacher as well, and my finance teacher. Those two teachers, I remember, were very important in my life. Of course, in the sum, all your teachers have influence on you, but there are some you do remember and say, ‘There’s a turning point in your life,’ and those are probably the six or seven that really changed. And you know, I really believe in encouraging teaching. It’s such a noble profession, such an important profession, and it’s, sort of, the basis of who we are today.

RLT: It is. It is. So, you were telling me about McGill and how you were the president of the students’ union. What was your major at McGill?

JMM: My major was economics at McGill.

RLT: So, you’re studying economics and you combine that with a very active career or trajectory in the politics of the students in McGill. First of all, how did you combine both, and how did you get interested in student politics at that time?

JMM: You know, I got interested more from the, like, service side, as opposed to the political side. So, I got involved in welcome week and winter carnival, you know, doing activities for students. So, I was probably more of a student-oriented student leader trying to change the life of students, as opposed to a more radical student leader trying to change the outside world as much. Obviously we got involved in many things in the outside world as well at the time, but I was more involved in-, I guess I liked leading people. I liked organising things. I’m good at that. And so, I think that student politics was a, sort of, precursor to my eventual business career where I’m, you know, running things. So, I viewed the student politics more as a chance to run something, more than an ideological basis.

RLT: Got you. That’s beautiful. And your undergrad major in economics, how was that? How did that provide the foundations for your future career? Tell us about it.

JMM: No, you know, at the time, in our high school, we didn’t have any economics. I really didn’t know what it was. I actually started in economics and political science and took both courses the first year to have a joint honours in that, and eventually I dropped the political science to do economics. I think it gave me a good background in understanding how the economics of the firm and how the economics of society works. I thought it was a good background, and it also gave me the chance to, you know, take other subjects. I took French, I took some other classes: I took some mathematics classes, took an accounting class.

So, by doing a single major – honours, they called it – it allowed me to get a good background in other areas. And then, when I won the Rhodes Scholarship-, my father had been a small town lawyer and he was the most open-minded father I can ever imagine. I can give an example of that, you know, whatever you want. But only one thing in my life he told me: he said, ‘Don’t become a lawyer. So, when I was accepted to Oxford, you know, at that time, they didn’t have an MBA at Oxford. So, you know, I decided to take a law degree, but more as a background as opposed to becoming a lawyer. So, I did the two years at Oxford as a law degree, but never took the bar, never became a member of the bar, never did become a lawyer. I actually went into business right away. I went to Harvard Business School directly after Oxford and became a business person, which I, sort of, knew was my field after my experience in the Swim School when it started out. But the law was a very good background.

So, I think, if you look at what you learn to do, McGill taught me how to lead, Oxford taught me how to think and Harvard taught me how to manage, in some way. So, I think those three things: each of the schools provided something different. But you know, the background in law was very helpful and the things we learned in that were really helpful. I was also co-captain of the ice hockey team in Oxford. I brought back the European tour, which they hadn’t done for 20, 30 years, and brought that back. And so, I also got involved in the ice hockey club when I was at Oxford.

RLT: That’s wonderful. You were saying that one of your professors at McGill encouraged you to apply for the Rhodes.

JMM: He was actually the president of the university. Because I was president of the Students’ Society, my direct interlocutor was the president of the university, at that time called principal, and he’s the one that suggested I applied for the Rhodes Scholarship. I didn’t really know anything about it. And he said, ‘You should apply for this scholarship.’ I looked it up and said, ‘Okay,’ and I applied.

RLT: And the selection process is one of the seminal parts of being a Rhodes Scholar, particularly the last round with interviews and everything.

JMM: Right.

RLT: So, do you remember your interviews, your final interview?

JMM: I remember it very well. So, at that that time, the process was, your application had to be approved by your principal. So, I put the application in to the university. The university approved it. Obviously, the principal approved it, because he suggested I apply, and then it went to a group. At that time, there was a small committee. They met at the Ritz Hotel in Montreal. The chair of the committee was Madame Jeanne Sauvé, who was governor-general of Canada. I don’t know if she was governor general at the time or she was just Speaker of the House at the time, but was a very well-known Canadian, very professional, very good. And then on the committee were several academics and some other people, including somebody I still see today, Michel Vennat (Québec & Merton 1963), who is secretary of the Québec committee and was on the committee. He’s the one who actually phoned me, and I still see Michel today. I saw him, you know, eight, ten weeks ago, which was a chance [guess 15:44] and I got to know him from that day, from that interview in 1979. Now, it’s 2024, so I’ve known him for a long time. 45 years, I guess I’ve known Michel.

So, you know, that’s the interview process, you know, got another friend. So, I went through the interview process. You know, I sort of believe that-, for us, it was great when I was interviewing, because I said, ‘Look, maybe I’m not the right person for the Scholarship, but I believe in the Super Bowl theory of life which is, on any one day, anyone can do anything. So, I said, ‘Hey, maybe I’ll get to do the lucky interview.’ You know, I think that the Rhodes Scholarship should take time to review selections to see if there should be more interviews, so they get those students better. Of course, for me, I had a good interview. It went well. So, I’m not complaining, but I think, as a process, not that they’ll miss out on the best students, but they may make a few mistakes than, you know, more interviews would have had. So, you know, we’re experts in scholarship. We’re, as you know, a Second Century Founder of the Rhodes trust, a major donation to the Rhodes Trust and others, and, you know, we bring together a group called the Global Fellowships Forum, which brings together the seven top scholarships in the world, and we work with them. And I think one area that some of the scholarships are doing more work on, and Rhodes could do more, is selection.

RLT: Yes. Yes.

JMM: I think there are things that the Rhodes will have to work a little bit more on introducing, spending more time, more money on selections, because selection is important, and I think the more time and money you spend on selection probably helps 30% in getting the very best people, but 70% avoiding-, not getting the people you didn’t want. So, selection is super important.

RLT: It’s so important. You’re right. Do you remember the questions, or was there a question that you remember that was either too hard or too original, or your answer?

JMM: Yes, there was. I didn’t get this question, but one of the questions that people said to me, you know, before the interviews is a famous question which is, you know, ‘John, it’s the end of your interview and thank you very much. But before you leave, John, you know, we’re at your funeral and you’ve got an open casket and we’re looking down on you and what would you like people around you to be saying?’ And of course, the winning answer was, ‘Look, he’s alive!’ So, I remember that question. I didn’t get that question, unfortunately, but I had the right answer for that.

But no, I think the interview was good. It was comprehensive. My thesis was about leadership, but also about Canada, and they asked me some questions about Canada and, you know, I think I gave some okay answer on that. I think in that year, we had two Rhodes Scholars from Québec. We actually had three from McGill: a guy from New Brunswick, Matthew Jocelyn (Maritimes & Lady Margaret Hall 1980), who is a playwright. And Matthew was very successful in his career, and he won the Rhodes Scholarship from New Brunswick, but he was going to McGill. And then we had the two Québec ones who were also McGill Scholars, Marc Tessier-Lavigne (Québec & New College 1980 who became president of Stanford University was the other one, and there was myself.

So, the two Québécois were Marc Tessier-Lavigne, president of Stanford, you know, world-famous academic, and me. So, I think that they tried to balance the, sort of, practical, rough and ready salesman, entrepreneur – me – and the more academic approach, with Mark. So, I think it was an interesting-, you know, if I look back at the committee, I think they, sort of, said, ‘Gee, we’ve got, you know, two sides of the world here, with two different people,’ and I think that’s important in some ways. You know, I hope that the Rhodes Trust doesn’t just get the person like me or doesn’t just get the person like Mark, but we’re able to have a selection process that gets the leaders in the individual fields, leaders in business and entrepreneurship, a leader in the academics like Mark, a leader in the theatre like Matthew. I think those are three totally different people. I mean, couldn’t be more different than night and day, but at the same time, three leaders in their individual fields. So, that was interesting, and I think that, you know, the selection process in Québec and also in New Brunswick and Maritimes was able to bring that out, or at least in 1980.

RLT: That’s beautiful. The Canadians and the Americans used to have the sailing, taking the ship to the UK.

JMM: Yes.

RLT: Did you guys also have that?

JMM: We sure did, yes.

RLT: So, how was that?

JMM: That was great, I guess. That was great. And it’s unfortunate they changed their schedule, Cunard lines. We took the Queen Elizabeth 2 over, from New York to Southampton [20:00] and it was interesting. You know, we got to meet, the Americans and the Canadians, right away, everyone. We had lunch at Rockefeller University, and it turns out my classmate Marc Tessier-Lavigne became president of Rockefeller University. Many years ago, he’d never have thought that, the day he had that lunch. And it was great, because we really got to know the group, and I think the only negative of that was we tended, as Canadians and Americans, to know each other better.

So, we created a small group over those five days in the ocean and we kept very together. So, we were probably less involved with the other Rhodes Scholars. What’s good now about the Rhodes Trust is there are more activities at Rhodes House, so I think, if we had the QE2 today and Rhodes House and the activities, but also Rhodes House being more open, we would have, as Canadians, more links with the South African, the Australian, the New Zealand, the German-, the other Scholars. Because of the bias of that boat trip, which I really recommend, because it did give us some great friends-, I mean, my friends today are the people I met that day on the boat, so that’s great. But I think that, you know, now, it’s even better-, it would have been better, because the Americans, the Canadians, but also the Rhodes House experience and your activities before and meetings, I think it’s good that all Rhodes Scholars are active.

You know, as a member of the Board of Trustees, I was chairman of the building committee that did the renovation of the Rhodes Trust building and, you know, I see the Rhodes Trust now, much more open and Scholars more interactive with the building, and so, we got a building that, you know, we worked on really hard to make sure there are different interests, timing-, you know, can students come in late, do everything? So, we tried to do that, and I think the new building is really open to that, and that makes the Rhodes Scholarship more valuable than it was in my day, because now, we’ve got much more interactive with Rhodes House.

RLT: So, when you were a Rhodes Scholar in Oxford, it was a very different experience from today, of course. Tell us, how was that? How was it to be a Rhodes Scholar in Oxford?

JMM: So, I can start when we landed in Southampton. So, we landed in Southampton and I’m, sort of, Mr practical organiser, business person. And the Warden met us.

RLT: Who was the Warden?

JMM: The Warden was Robin Fletcher, and the Warden met us, actually, with one of the Scholars from Canada the year before, Jacques Hurtubise (Québec & Trinity 1978), and they were standing there, and we got off the boat and we’re all standing around, sort of, wondering, ‘Okay, what’s next?’ I’m, ‘Hmm, where are our bags?’ And then, so, I asked Robin Fletcher. I said, ‘Where are our bags?’ He goes, ‘Very good question.’ ‘Okay.’ I said, ‘Where are our bags?’ ‘Excellent question.’ I said, ‘Okay.’ So, I said, ‘Seems our bags are down here. Why don’t we go down the stairs and take everybody there?’ ‘Oh, okay.’ So, I brought all the group downstairs to get our bags and then they told us, as we were getting our bags, that ‘By the way, take one little suitcase for the bus to Oxford: a) we’re going to stay overnight in Southampton and b) when you go the next morning to Oxford, three days later, your stuff will arrive. And by the way, I hope you have sheets for your bed, because you’ll need that for your room and all that.’

So, everybody was-, it was chaos. And I just immediately saw, I guess, the, sort of, practical, Canadian, North Americans, myself, and the very theoretical English background, not thinking through all the little details. It just hit me very hard. So, that was my first experience of Oxford, which wasn’t bad or good, it was just different, right? And so, I remember a lot of people sharing sheets and trying to arrange for the first three days, until their bags arrived. You know, North Americans would have arrived and driven through the night to get to Oxford the first day, right? We wouldn’t have had any of this where we’d have a big truck follow us. So, it was just interesting, how that came.

RLT: You went immediately to college, to Wadham?

JMM: No, actually, we were on Holywell Street, just off there. We had a little place where I met-, Gordon Crovitz (Illinois & Wadham 1980), who was a Rhodes Scholar I met on the boat, who was from the University of Chicago. Gordon and I are still good friends today. Gordon was a roommate in Holywell Street. Gordon was writing at the time for the Wall Street Journal and his career became publishing the Wall Street Journal. So, Gordon, a very successful Rhodes Scholar, and we had three flats there and he was one of the roommates in the flat in Holywell Street at Wadham, and then, we went out to university housing the next year.

RLT: Okay. That’s great. So, that was the arrival. And then, what else comes to mind?

JMM: The chance to travel in the summer was great. You know, I did travel that summer, which was a great experience. The summer between the years at Oxford was a great experience. I had to work every other summer and I worked, actually, for a Rhodes Scholar who was general counsel to Canadian General Electric. I worked for them the summer before, in Toronto. But the summer between years, I was also able to travel and I took advantage of that with the Eurail pass and Interrail Euro. I think there are two of them. I can’t remember which one I used. And I went to Europe and that gave me a great opportunity. That travel was great.

So, I think, you know, I look back on my Oxford years, I really learned a lot in the law area, enjoyed that. I’m glad I did it. I didn’t become a lawyer. I didn’t want to do the one thing my father asked me not to do. I didn’t break that rule. But I did learn about the law and use it every day in my philanthropic and also our business work. Secondly, I got more involved with ice hockey and my organisational skills were used there, organising this European trip. Thirdly, was able to travel and really got to know the continent, got to know Europe better, and really enjoyed that. And I think, in Oxford, you know, I was studying, being with Rhodes friends, but also being with college friends and working the hockey team. So, those were my major activities and, you know, it was a good two years, a great two years.

RLT: That’s great. Did you have your yearly appointments with the Warden.

JMM: Yes, we had. Once a year, you’d see the Warden and you’d, sort of, come into his office and he’s sitting behind his desk and you talk for ten minutes and you leave and then there’s the Coming Up Dinner and the Going Down Dinner, and that was it. They also had a ball, though, at the Rhodes Trust, and I couldn’t afford to go to the balls everywhere else, which were £80 or £100. The Rhodes Trust one was cheaper, so I did actually go to the Rhodes one. They had a ball there, I remember, at the Rhodes Trust at that time, and they stopped it and they restarted it more recently, which was a great thing. So, I remember, because I couldn’t afford the ones for the other colleges which were, like, £80 or £100 at the time. So, I went to the Rhodes one, which was either free or very cheap, and I remember that. So, it was nice.

RLT: That’s great. You have mentioned already several friends that you made from the Rhodes community at that time, but I guess that you also made some other Oxford friends at the time.

JMM: Yes. You know, it’s interesting. I did make some other Oxford friends, but most of my friends at Oxford, it turned out to be, were the Rhodes Scholars and most of them whom I met, you know, in those North American and Canadian ones. So, I’m still very close. Best man at my wedding was a Rhodes Scholar, some of my best friends, sat on my board, two of the Rhodes Scholars. I keep in contact every day. You know, people I meet all the time. I think my Oxford experience was more linked, actually, to the Rhodes Scholars, although we had less activities, because I got to know them. I was not-, you know, the English students were younger, because I did an undergraduate degree in, like, a graduate degree. So, the other students were young. We were, sort of, 21, 22, 23 and they were, sort of, 17, 18, 19. So, we tended to stay more with the Rhodes Scholars whom we got to meet. A lot of Canadians, Americans. So, I’ve had, you know, good long-term friendships with many of the Canadian and American Scholars to this day and talk to them often.

RLT: That’s great. So, we know the criteria from selection. We know fighting the world’s fight. But how would you define a Rhodes Scholar, based on your experience and your classmates at the time? What makes a Rhodes Scholar?

JMM: So, I mean, I think they’re interesting. At least, I found that, you know, if you look at my time at McGill, when I was more involved with student politics, the, sort of, group there, or my fellow students in economics or students at the residence, and at Harvard Business School where there were more business-oriented people-, I thought-, you know, there’s a variety of subjects. What I liked is the fact that the Rhodes Scholarship brings students from every subject area, so a theoretical physicist to an economist to a global health person to a student in law. That diversity of students from all different subject areas is very important and their work is a foundation of the Scholarships. They’ve always tried to do that, with a diversity of subject areas.

So, that’s one of the things I think is important in the Rhodes Scholarships, in my friends that are Rhodes Scholars as well, is that diversity. I think that several, but maybe less than we think, became leaders in their field, which is good. So, I think that, you know, again, it’s having more variety, maybe, in Rhodes Scholars, to have more leaders in different fields. I think we’re very strong in the academic field, some politicians as well, and a few businesspeople, a few entrepreneurs. I guess one thing I’ve noticed with the Rhodes Scholars, on average, compared to myself – and I’m obviously off the scale on this – is the ability and willingness to take risk. I’m definitely a risk-taker and, you know, if somebody has got to go forward, I’m the one that stands forward. And, given the, almost, pillow or cushion that a Rhodes Scholarship gives you in terms of success in the future, I think Rhodes Scholars take a little more risk. And, you know, I mentor a lot of Rhodes Scholars and I meet them. I do say, ‘Look, you know, take a risk. There are so many people that want to do the traditional role.’

So, you know, if we’re looking in this project, in your oral history project, one thing I could, sort of, suggest to future Rhodes Scholars is, you know, take that risk, do that different thing. You know, the most dramatic example of that is probably this kid who is 17 or 18, and he takes lighter fluid and he puts it in his mouth in Québec City and he blows out the fire, and that’s his job. You know, that was his job. He’s a busker, you know, and he shovels things. So, where is that busker today? Well, he really liked doing that, and he, sort of, [30:00] thought about it an awful lot, and he realised that circuses around the world did this, had acrobats, but they also had these animals coming by and he just thought that he didn’t need animals and circuses. So, Guy Laliberté, this busker in Québec City, went to Montreal, which was a world-leading circus school, and he got some people in there and started Cirque du Soleil, which is a multi-billion-dollar company.

RLT: Wow.

JMM: From the guy that really had his passion, and he took some risk. And, you know, I don’t know Guy Laliberté, but if you look at his background, from starting as a busker, to keeping his one field to be a world leader in circuses-, you know, he invented circuses with more music but without animals. You look at that and say, ‘Wow, look at the risk he took.’ But look at the downside he has. He had nothing to lose also, but he had nothing to gain, in terms of, he didn’t have somebody at his back to fall on, you know? And so, I think that Rhodes Scholars should look at Guy Laliberté. You know, he’s a genius. You know, if you’re good at something, follow your passion, take that risk. And, you know, I look at what he did with Cirque du Soleil, it’s just amazing, you know, and you hear stories like that. So, you learn in business and also in activities in the world, that every area you can be really good at, if you’re passionate about what you’re doing, and if you’re good at it, you can do very well.

RLT: Yes. Thank you for that, and I think we will go back to the mentorship and some of the advice that you have, because you have spoken several times at Rhodes House and I have had the pleasure to listen to you. The last time, I think, it was 60 rules.

JMM: Right. I’ve turned 65. It’s 65 rules now. Where is that poster? I’ve got that poster somewhere here. Anyway, it’s 65 rules now.

RLT: We’ll talk about that later. I’m very curious about that and also about your advice for Rhodes Scholars. But you finished your degree at Oxford, your undergrad law, and you mentioned you went immediately to Harvard Business School. That’s extraordinary.

JMM: Yes, that was interesting. One of the Oxford Rhodes Scholars who was on the boat – I met him on the boat – William Altman (Texas & Pembroke 1980) from New Ulm, Texas, and I became friends we were both, sort of, interested in business. So, we sat at his manual typewriter and typed out our applications to Harvard Business School together and we both got in, and he was section G and I was section C. So, you know, the Rhodes Scholar network followed on from there, and so, to answer your question, I left Oxford to go directly into Harvard Business School. They accepted the fact that I was a little older because I had had two years at Oxford, and also the business experience, my swimming company and, you know, running student politics as my, quote, ‘business experience.’ And so, I walked into Harvard Business School in 1982, to 1984 and I was 24 to 26 and I got my MBA there. A very different experience to Oxford. Still had a few close friends there, but probably not quite the diverse, in-depth network of friends I had at Oxford. And then, from there, I went and worked for a company in Montreal for three years and then took the big step to become an entrepreneur.

RLT: I wanted to ask you, is there a Harvard Business School case based on your business?

JMM: There’s a small one, based on what’s called a critical fractile. When you delivered Auto Traders to the store, how many did you collect and what the cost of overage and the cost of underage. There’s a small case on that. I don’t know if they still use it. We’ve thought about. I mean, they’ve talked about doing something bigger and it’s a) time and b) confidentiality.

RLT: Yes.

JMM: We haven’t done that yet, it’s a great story. So, when I left the company I was working with, Power Corporation of Canada, to, you know, launch on my own to buy Auto Trader in Montreal, called Auto Hebdo, and then built that around the world from 1987 to 2006, 19 years, you know, that’s an interesting story.

RLT: Yes. A wonderful business case. I was just wondering, because we would use it also here for Rhodes House, that business case, that HBS case, but that’s for another day. So, after business school, you said that then you went to work for a company.

JMM: For three years. Yes.

RLT: When did entrepreneurial work begin really pushing you?

JMM: So, you know, I think I was always an entrepreneur, because I had that swimming company. I actually started a fruit stand as well. So, I had some small businesses when I was a kid, and when it wasn’t a small business, I was running something, I was running the McGill Students’ Society, I was running the hockey team. And so, I guess I always had that entrepreneurial spirit. I worked for this company and it was really a company owned by an entrepreneur who started from nothing, Mr Paul Desmarais Sr. So, I thought, you know, that I’d go work for them to see how he reacts and what he does. So, I worked there for three years, got a little time with him. He was, you know, older at the time, but still head of the company and I was able to watch him and his son Paul, who’s a great entrepreneur as well, and to learn from them.

But I still realised that working for someone else wasn’t, sort of, where I wanted to be and probably where my skillset wasn’t as good. So, I’d always gone to Toronto on business and saw the Auto Trader there and just figured, ‘Jeez.’ You know, it sells for five times a daily newspaper, but if you unfold it, it’s smaller than a daily newspaper and yet it has 100% ads versus one-fifth ads. So, it’s really one-eighth the cost. I said, ‘Gee, that’s interesting business.’ So, when the one in Montreal became for sale, I went and bought that, and that started my career in Auto Trader and classified advertising in general. We became the world leader. We were in 23 countries. We were the largest publisher of any publisher in Russia from 1996 to 2006. And so, we ran that business from 1987 in Montreal, then bought a few others across Canada and then bought most of Canada, moved to France, I bought the French paper and then started growing around Europe and then moved to Geneva to be a central place where we could run the business for the long term out of there, and it became a very big business. So, we had about 7000 employees at one time, across the world, and that was great, you know. And I think it was, you know, things I learned from Oxford. I used my law degree a lot from Oxford. I used my, you know, leadership training and doing things, and also having been able to work with these great people and great teachers, I thought I was well equipped to do that, and it turned out very well.

RLT: Did you take the company public, or did you say it remained private?

JMM: So, actually, we were private from 1987 until 2000, and we were the last person in the world to get out before the .com bubble burst. We were the absolute last person. So, we priced our deal on the Wednesday. It was called trader.com, to get the internet multiples. We had a very high valuation. It was priced on the Wednesday night, but because we were public on the NASDAQ and the Paris Euronext Stock Exchange, it didn’t actually trade until the Friday. But we hit the peak and the mark started going down on Thursday, so by the time we hit Friday, our stock just dropped the second they went public. We got all the money at $30, but I think the first trade was at $27 and then went to, like, $19 the first day. So, we were very good at timing. Sometimes, that’s more luck than good management, but that luck we had by getting out that one day. If we were one day late, there would have been no public issues.

So, we were public from 2000 and in 2006, I basically sold the company. We didn’t sell it all but sold by parts and the money was dividended up and dividended up to public shareholders, including myself, and the company was liberated. So, we basically sold the company in parts across the world to different people, and we sold it into five parts, and we sold all the business. And then, we decided, ‘Look, what are we going to do with our life?’ We decided to become philanthropists, and so, in 2007, we started the McCall MacBain Foundation, and so the story goes on and the philanthropic group goes from there.

RLT: That’s great. So, first of all, you grew a company, you scaled it up, you went public, you remained there and you sold it. How did your leadership style evolve from the entrepreneur leader to the president and CEO of a larger company and a public company that was active in places like Russia and around the world? How has your leadership style evolved?

JMM: So, it’s interesting. I don’t think it evolved as much as maybe it should have. So, we were obviously very respectful of-, we’re big on, you know, proper accounting and proper documentation, etc. So, we were, you know, a good public company in that way. But I was a controlling shareholder when it was public and when it was private, so I always viewed it as, you know, we’ll do what’s best for the business.’ We weren’t there to have short-term profits. We invested for the long term.

So, I always ran it as an entrepreneur private company, and I had help. I hired a really good number two president, chief operating officer, Didi Berton [guess 39:05], who did a great job. I hired, you know, good financial staff to have a good CFO who could help me also on the earnings calls etc. So, we still ran it as more entrepreneurial organisation, but you know, I think more companies should run like that. So, we ran it as an owner-managed company and, you know, I think great businesses are owner-managed and we’ve seen that in the past. I think we’ll see it in the future. So, you know, I ran it day to day and we built it up and I had help with that and we had some great people. We tried to create, [cannot decipher 39:35] a management style. We tried to create a loyal team around it.

So, a lot of people are with me today. I’m 66 today and, you know, the head of my investment committee, I met at Harvard Business School, the people who are head of my family office, I met at Oxford in 1980. So, you know, there are a lot of people who have been around me a long time and [40:00] I think we make decisions quicker and better because we know each other, know our culture, have a cultural honesty and directness and an understanding of where we want to go. So, that was really good. So, we’re probably different than other businesspeople: more loyalty base, we want to have a great team that works together for a long time. People make mistakes. We’re, sort of, open to that and, you know, ‘Let’s move on together.’ They’ve done great things and so, we’ve had a team that’s been with us a long time and that continues today.

RLT: That’s one of the main lessons of leadership, right? The teams that you build and you keep around you.

JMM: Right, right. Exactly, and I think, you know, what we want is a good team who’s there for us in the long term and hence, we make good long-term decisions. You know, they might not be the world expert in one thing at that time, and we can hire someone from the outside as a consultant if we need to. But, you know, we want those people to think long term and have the same culture and values as we do. So, that was really important. I think that, you know, back to my grade 7 geography class, Mr Weibrau [guess 40:58], you know, we always joked when we were living in Paris, we said, ‘Gee, I have more chance of knowing the real value of the classified advertising paper in Santiago, Chile than I do of the value of the apartment right next to me,’ you know?

So, I think we learn very much as a businessman to focus on our area and then, since we’re only in one area, we can actually go international, as opposed to, you’re in many areas and hence, you know, it’s just too complicated to go international. So, we were able to have a business in 23 countries. We were the leader in classified advertising in France, in Mexico, in Venezuela, in Colombia, in Argentina, in Spain, in Belarus, in Ukraine, in Russia and China, through real estate, in Taiwan, all of those. So, I think we created a unique-, one of these leadership styles was decentralisation.

RLT: Yes.

JMM: So, we were very good at creating profit centres and having people who, you know, ran those profit centres. So, we had a very small headquarters at that time. Of the 7000 employees, we had only, you know 50 people at headquarters. So, we tried to have a very decentralised organisation close to the actual businesses in each country. So, those are the sort of management styles I, sort of, developed or learned, given the business and given our background.

RLT: During that time in business, in that phase of your life, what is the toughest decision you’ve faced?

JMM: Yes, well, we faced a lot. I guess one of the tough decisions was, you know, leaving Canada to go global. So, that was a big decision we had. My son had just been born a little while before. I had two kids at the time. My daughter was entering kindergarten. And, you now, I said, you know, ‘We’ve got a big business in France. We should probably move to France.’ But that was a big decision, moving to France with two young children, but I also realising that I had to get to France now, because you want your kids to go to kindergarten in France to do grade 1, because CP or grade 1 – Cours Préparatoire in France – is the most important year of your life. So, you don’t want to go into France, say, ‘Oh, just walk into CP.’ You want to have the experience of kindergarten.

So, I was able to move to France so my oldest went to kindergarten in Paris, and that was a big change. We moved from Montreal to Paris, started a new life in Paris. And then, that allowed us to develop our business, not only in France, but throughout Europe. And so, from 1992 to 1998, I lived in Paris and was able to, you know, with the family, grow there. I had another child born, actually, just during the time when we owned a business in France – we didn’t live there – and then moved and, you know, had the kids educated in French from that point on.

RLT: Wonderful. How were those years in Paris for you and your family?

JMM: I mean, I love Paris. It was a great time in Paris. We built the business into Sweden and other countries. Paris is great: great connections, everything. It’s a big city. We’re big skiers. So, it’s a little far from the ski hills. So, one of the reasons in 1998 we decided to move to Geneva because it’s closer to the ski hills. We could ski every weekend, and that was an important thing. So, we moved to Geneva in 1998 and continued the business until 2006, when we sold the parts.

RLT: When you sold the business, how was the day after?

JMM: You know, we sold the business in parts, so the day after came when the last part was sold. So, you know, we had some reflection: what did we want to do? And we sold for cash, so we had cash and we decided that we’d basically give most of our money away, and that was a decision made in 2006. So, in 2007, we started the McCall MacBain Foundation, a Swiss-based foundation. We worked in many areas. First, we worked in maternal mortality issues and then we transferred. We didn’t think we were having as much effect as we should there and we work in three areas now.

Our main area, as you know well, is scholarships. So, we’re world leader in the donation of scholarships. We’re leading donor at the Rhodes Trust, leader donor at the Mandela Rhodes Trust. We created scholarships around the world, including the Kupe Scholarship in New Zealand. We created the McCall MacBain Scholars at McGill in Canada, The Loran Scholars Foundation, these scholarships all over the world. So, we sold the business and with that cash, we developed a foundation that works in three areas. So, about two thirds is scholarships around the world and, as we said earlier, leadership scholarships, wide subject areas, not just one subject area.

Secondly, 20% on climate change, which I think is a major issue in the world, and we work in several areas in that: nature-based climate solutions in Canada, work on the Global Methane Hub worldwide, and I was founding chair of the European Climate Fund issue. And then thirdly, work on youth mental health, which has become a major issue – about 5%, 10% of our funding – and that’s linked a bit to our scholarships, but getting our links with universities. So, we do a lot of that work. Universities we know around the world, but especially universities in Canada. So, got our customer proposals from a university in Canada as a second round of major donations in mental health.

So, we’re trying to help youth mental health in Canada. Tough issue. Youth mental health around the world is tough. So, that’s our third area of work. So, I guess, to answer your question directly, the transition was tough. I was used to running one business I knew very well, and now, I have two things to do. Philanthropy, I don’t know very well, and looking at investments or businesses we’re going to buy. But we’ve had some interesting things, since we left, on the philanthropic side. We’ve created, I think, a great organisation of people in our foundation who help us work on scholarships, on climate change, youth mental health, and also, we have a general area for things that come up, with disasters, etc. We try to help them. So, they have that part of my time.

And then the second part is really the business side. We kept in business. We still own operating businesses. Some we own-control, some we don’t. But during the COVID pandemic of 2021 to 2023, or whatever it is-, yes, around there, we thought, you know, did we want to buy some businesses that are pretty solid? And they’re good, and some are involved with individual support. So, we bought Wilier, a Tour de France bike company. So, we’re making bikes in the north of Italy. The biker Mark Cavendish won the most stages of the Tour de France with our bike, the Wilier Filante, and then we won silver medal at the Olympics in the Filante as well. So, we’re happy about that. We also invested in MAAP: it’s a bike clothing company. And then, in the middle of COVID, I said, ‘Gee, you know, although our foundation, we’ve given money to perpetual scholarships,’ because I was always worried that the investment-, what if you make some bad decisions?

So, I said, ‘What can I invest in that would last forever?’ So, I told one of my guys, I said, you know, ‘Go and buy the Eiffel Tower.’ And sure enough, he couldn’t buy the Eiffel Tower. I said, ‘That was a good thing. It will last forever. Well, let’s go buy the CN Tower in Toronto.’ So, true story: I had this Harvard MBA who was Nigerian Harvard MBA student, and I hired him for the summer, and I said, ‘Look, go and find out who the CEO of the CN Tower is and who owns it.’ And he came back, he said, ‘John, you won’t believe this.’ I said, ‘What is it?’ He said, ‘Well, it’s owned by Canada Lands,’ which is a 100% subsidiary of the Canadian government. I said, ‘Yes, and who’s the president?’ He said, ‘The president’s name is John McBain’ the same name as me, it turns out. True story. This only happens to me.

So, of course, John MacBain sends an email to John McBain, the guy responds right away. No relation, but it turns out he was born 20 kilometres from my hometown, in Port Colborne. I was born in Niagara Falls. And, you know, we talked a little bit about it. He thought maybe we could take a management contract, etc. And then it turns out, he retired, and someone else took over, and they weren’t interested in that. So, I’m still thinking, you know, ‘We need something to last forever.’ So, we ended up buying into, and now we’re a partner with three cousins in, Bondinho, which is the Sugarloaf mountain tram in Rio de Janeiro. So, that was one of the investments. So, I’m heading to Rio, actually, in ten days, for the wedding of one of the cousins. And, you know, that was a great investment. It’s really something that is going to last forever, and they actually have rights to the land, so it’s not as if it’s a concession. So, I think that’s a great investment we’ve got. So, we’re looking around the world for gondolas and other things like that. We think they’re really good investments if they’re unique properties in the world.

RLT: Yes.

JMM: So, that’s what we’ve done since then. So, it’s a little more difficult, in that I don’t know the business as well as I do, but I get more variety in my life in terms of that.

RLT: Yes.

JMM: We’re used to running things. Now, we have, sometimes, minority positions. In both the biking company, the bike clothing company and the Bondinho, the Sugarloaf, we have a minority position, but we work well with the partners and I think we’re seen as a valued customer. We have a very long-term time horizon. We don’t need to sell anything. So, I think that’s been important for them. So, we’ve been a fairly good partner, hopefully, for these people and we hope to continue that in the future. So, we’re still looking around for interesting businesses to buy. We’re growing, and then, of course, we have an investment portfolio as well. All those things. You know, in the end, beneficial ownership is the foundation for all our future profits, and sets up money and gives more away.

RLT: Thank you. And now, I would like to introduce this segue. You mentioned at the beginning when you were talking about your foundation [50:00] that scholarships is almost two thirds of that and one of the most important aspects of your life, and you are so important to the Rhodes Scholarship, being the Second Century Founder. You came at a time when we know the Rhodes Trust was in dire straits and basically, thanks to your generosity, the Rhodes Trust exists again in its form today. But can you tell us about that time/ How did you learn about the situation in the Rhodes Trust? How did you know what had happened, and what was the story about you jumping in and playing that role?

JMM: So, we started working in what we thought was the greatest need in the world: some maternal mortality issues in Africa. We worked on that, found that was hard to do, wasn’t as successful as we thought. We learned, really, two things, I guess. One is that a good philanthropic gift is one taking a problem, hopefully a large problem, that you have a decent chance of success on and that your cost for success is reasonable. And with the scholarships, we found that it was, you know, a trusted institution. So, we knew that if we gave our money on these institutions, or if we started the scholarship on our own, we knew where the money was going. After doing some things in Africa, we were always concerned about, you know, corruption, etc.

So, that was something that, you know, made us look more to education scholarships. I guess secondly, I was a Rhodes Scholar. I was a scholar at McGill. I was a Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation scholar at Harvard. So, I was the result of scholarships, so I wanted to, sort of, give back in that way to scholarships. So, it’s more like, you know, you want to teach a person how to fish, not cook them the fish. So, I think that was important to us, and we, sort of, knew and understood scholarships. So, at that time, we were, sort of, thinking what we should do at our foundation, and Don Markwell (Queensland & Trinity 1981), who was the Warden of the Rhodes Trust at the time, called me and said, ‘Hey, John, would you like to join the board? We’re revamping the board.’ So, I did and I started learning, you know, some of the mistakes that were made by the Trust and why they got into some problems. And so, I saw that, and I saw that, you know, somebody has got to stand up and do something otherwise this scholarship is going to go down, and I just said, ‘Gee, well, they need a lot, they don’t need a little.’

So, we made our largest gift at the time, £75,000,000, to the Rhodes Trust, and I think with that hope to a) help in itself and b) encourage others, and I think it did both. Obviously, the money itself, we gave help, but we were able to raise, you know, tens and tens of millions of pounds from other people as well, given that donation, and now, the Rhodes Trust is, you know, on a much better financial footing. You know, I’m always concerned about governance. So, governance will be important to make sure we don’t get into trouble like that again. When we started the McCall MacBain scholars at McGill, for example, in Canada, we wanted to make sure that we funded it properly, that we had also, you know, an arrangement with the university on fees, to make sure that we didn’t get caught by some arbitrary movement of fees. And we know the British government increased the international student fees with the universities and, you know, the Rhodes Trust didn’t get any extra funding for that. So, that really was tough on them. That plus some other investments, etc., you know, probably led to us having to get money. You know, and we gave it a positive sense too. Yes, we had to help, but this thing-, we also said, you know, ‘This will help grow the Scholarship.’ So, you know, we look back-, how many years has it been since then? Over a decade now.

RLT: Yes.

JMM: So, ten, fifteen years. You look back, so, yes, you know, it’s not just, ‘We saved it and now we’re back where we were.’ You know, we’re not only back where we were, we’re 20, 30 Scholars more. We offer Scholarships globally now. We have a Scholarship student from UAE. We’ve had students from all over the world. We’ve had students from China. We’ve had students from Russia, you know, and I think that’s great. So, I’m very happy with that twofold vision I had: one, to put the Trust on a sound financial basis, and two, to have the Trust as a global scholarship. I think those have been successful and obviously, you know, it can be more successful and over time, we hope it will grow, but I think we’ve kept our core values in that. You know, I believe in the Scholarship, the growth of the Scholarship itself. I’m happy with where we are today, thankful that our money was able to help a) stabilise the Scholarship, as you mentioned, but also b) grow it to the future, and a successful future.

RLT: And was you were mentioning, it was energising the community.

JMM: Our class leader programme, right.

RLT: Exactly, and I think that was equally important. John, you were instrumental in leading the 110th anniversary reunion where the campaign was launched, so, tell us a little bit about that reunion and your role, and how it was.

JMM: Sure. It was interesting, Rodolfo. What I said is, what we were doing the first time is getting money from Rhodes Scholars and some big donations. We’ve done that part. How do we get Rhodes Scholars interested, to make big donations or small? And one of the things big donors want to see is that the community itself has given. So, that was important to me. And, you know, I thought back and said, ‘Gee, what is the number one place in the world, in universities at least?’ I guess there are two great fundraisers in the world. There is Princeton University with the example of, you know, how well they raise funds, and probably the second is Ducks Unlimited, believe it or not, who has these dinners where-, you don’t want to go. They’re unbelievable fundraisers! I think Ducks Unlimited is, like, the second largest conservation organisation in the world. But those two are, you know, the penultimate. And I think, you know, given the Rhodes Trust, I think Ducks Unlimited maybe isn’t our best bet.

So, I looked at Princeton, what they were doing, and I said, you know, ‘Each one has a leader for the class.’ And, you know, we didn’t know how it would go: you know, the Rhodes Scholars might all join. So, we said, ‘Let’s make it a class leaders plural programme,’ so we could have more than one leader in each class. So, it’s much more participatory. So, Erica Mirick and I, you know, me in Geneva and her in London, split up the calls and we called everybody we thought-, from every class back to, I think it was-, we had some before 1950 and up to, I think it was just before-, this was just before New Year’s Eve. We were calling people, trying to get-, because I wanted one for every class, and I think we succeeded, with two or three in the 1940s, but we had 1950 class on, at least one class leader for each year. And I think that was important because it brings-, as you know, you’re a Rhodes Scholar, but you only know people plus or minus one or two years from where you were, especially your year.

So, by bringing the whole Rhodes community together, that’s great, but they don’t have any affinity. The affinity is within their classes. So, we had to make a touch point with Rhodes House more top-down, but also a top-up approach, which is the class leaders. So, you know, I still encourage the class leaders. I’m involved in the calls still. We’ve had, you know, great luck with them. And it’s threefold, really: bring news of Oxford Rhodes Scholars to the community and the leaders to pass that on; number two is the leaders to bring together their class, do activities, keep them informed, communicating; and number three is to have them say, ‘Hey, can you give back to the Trust, in small or big ways, in continuous small ways or in big gifts as well.’

And I think that the class leader programme is super important, because the Rhodes Trust, for somebody three years ahead of me or three years behind, I don’t know anybody, but I know my class and I’m still seeing them today 40-something years after, right? So, 44 years after, I’m still, you know, talking to my Rhodes Scholar friends tomorrow. You know, I talked to them last week. So, that was linked to my class, and so, that’s class needs leadership, and so, we developed leaders in each class. I’m in the class of 1980. I think we had three or four or five leaders in our class, and that was great, and I was one of them. Yes, I think it’s five leaders in our class. Some of the classes had three, you know, when we get in the 1960s, 1950s. We were so happy to get one, but, you know, that was great. You know, as this oral history project goes on, I encourage the Rhodes Trust and Scholars to make sure that keeps up, make sure we keep up the class leaders, make sure they’re seen as their dual role: not just fundraising or not just communications. That we keep them there. And, you know, some are more interested in communications work, some are interested in fundraising. That’s great. Have two or three for the class and one person does one thing, one person does the other. I think that’s the way to succeed. And also, it culminated in bringing together all the Rhodes Scholars. So, the class leaders were able to go down to their class and say, ‘Hey, come to this 110th anniversary.’ So, the 110th anniversary, we had it in 2013, was it?

RLT: Yes.

JMM: So, the 110th anniversary of the Rhodes Trust, it was twofold. The 100th was in South Africa, which I went to, and the one in Oxford. I was involved in was the 110th, which was in 2013. And so, we looked back at the 100th anniversary and we saw, you know, some great formal activities: Nelson Mandela was there, Bill Clinton, etc. And the 110th anniversary, we wanted to bring all the classes together, to show the rejuvenated Rhodes Trust, right? The rejuvenation of the Rhodes Trust started a little bit with the 100th anniversary with, you know, giving money to the Mandela Rhodes, but the Scholarship was more of the same. I think that with the 100th anniversary, bringing Scholars in 2013 to Oxford, class leaders helped that and we really had a community sense of back and forth among the Scholars, and that really launched, I think, the next generation of the Rhodes Scholarships.

So, from 2013, the 110th anniversary, to today, 2024, 11 years later, you know, we can see the Rhodes Scholarship has changed. We’ve got much more involvement of the current Scholars, in Rhodes House and with themselves, with all the other Scholars. We’ve got more Alumni, inter-Alumni and Alumni Scholar work. I do mentoring of Scholars. We have activities and programming. I speak at them. We’ve got, you know, things I listen and go to. We have anniversaries every so years. We have, you know, more people saying, ‘Hey, we’ll just do an anniversary for our class.’ So, in the 120th anniversary, I guess 2023 [1:00:00], you know, we brought our class together first, the class leaders got together, and we brought the class of 1980 together at a small outside Oxford for three days, and then we came and joined the 120th anniversary in Oxford, and I think we weren’t alone in that. So you know going back to a circle of the 110th anniversary I mentioned that I ran in 2013, I think that shows, you know, there are two things that work there. It’s bringing all the Scholars together and having the class leaders, and the 2023 one, the 120th, was the result of having a reunion for our own class and also having a renovated Rhodes House. And, you know, as chairman of the building committee for the Rhodes Trust, we’re very proud of what we did there. The building is in great shape. Now, it’s more open to the world and open to the Scholars – I think that’s important – and open to Alumni and our community.

RLT: So, was that your vision, with chairing the building committee, to make Rhodes House a much more open and inclusive place?

JMM: Yes, much more open and inclusive. I think it was almost like a mausoleum, you know? And even the entrance. Remember that entrance we had: you’d walk through it and there was the echo and you’d hear your heels come by and there was, sort of, nobody. It was just-, so, we said, ‘How do we open it up? How do we make more meeting rooms?’ And I was very concerned with entrances. So, ‘How do we make it such that people can be in the building after hours, etc?’ And having different interests, separating the office function from the, sort of, event function, which could be a third party paying money, which is a great help to us, and still allowing the Scholars to have their side of it, and to have accommodation.

So, I think, with the new building, we’re able to do all of that and in way that’s consistent with the architecture. I’m, as you know, an economics major and a law major and an MBA and I’m a businessperson, entrepreneur, 100%, or maybe now a little bit of a philanthropist. I’m not an architect, I’m not good at it, but I love architecture and I do understand spaces and my wife and I together have made several homes and office renovations and we’ve always started from first principles. And so, I took on this project and actually, the Rhodes Trust had a committee, and I was the chair of the committee, so, I said, ‘We’ve got to choose an architect,’ but, you know, I had this fantastic architect in Vancouver, and I said, ‘Look, you know, we’re going to interview all these architects. Why don’t you come over to Oxford a few days earlier and interview them all?’ And he interviewed them all and said, ‘This is the one you’re going to choose.’ I said, ‘Okay.’ I just kept it in mind. I said nothing. And sure enough, the whole committee got together and sure enough, said, ‘We chose that one.’ So, I said, ‘Okay.’ So, I trusted the committee’s choice, but I also knew that a real world-class professional architect who I knew also had the same choice, and that choice, the architect is very good. We’re very happy with the architects.

And by developing the space and understanding the space and using the space below, digging out that space-, and there are some options I left there. So, in other words, you know, I was at Wadham College, Oxford, which is the next property, and I’ve always dreamed that-, you know, when we made the underground thing, we had the big lecture hall, a big hall that holds maybe 100, 200 people, you know, it’s near the border with Wadham. And so, you know, I’ve always thought, if you ever want to expand, you know, we’ll get together with my friends at Wadham and we’ll push that underground and we could have another set of, you know, buildings or accommodation under there, or a bigger meeting room. And we looked at everything. So, you’ll notice we have entrances both from the front and the side. The side is nice, because it brings people down, you know, through our gardens, but also opens it up a bit to Wadham if we ever did anything that way. But the second thing of the opening was – back to that mausoleum – we were able to open up – and it’s the architect’s doing – by having that cylindrical staircase, the circular staircase going down from that. So, it made the rotunda, which used to be some place you walk through and you see mail around to a place, an entrance. You have a choice: you can go around and go to the other room, or you can go down this big, beautiful opening.