Born in San Francisco in 1945, Jim O’Toole studied at USC before going to Oxford, where he took a DPhil in social anthropology. On returning to the US, he served as Special Assistant to the Secretary of Health, Education and Welfare. He chaired the Secretary’s Task Force on Work in America and was Director of Field Investigations for President Nixon’s Commission on Campus Unrest. From 1994 to 1997, Jim was Executive Vice President of the Aspen Institute. He has also held the University Associates’ Chair of Management at USC where he served as Executive Director of the Leadership Institute. He has written eighteen books and been the editor of New Management magazine and The American Oxonian, and served on the Board of Editors of the Encyclopaedia Britannica. This narrative is excerpted from an interview with the Rhodes Trust on 12 March 2024.

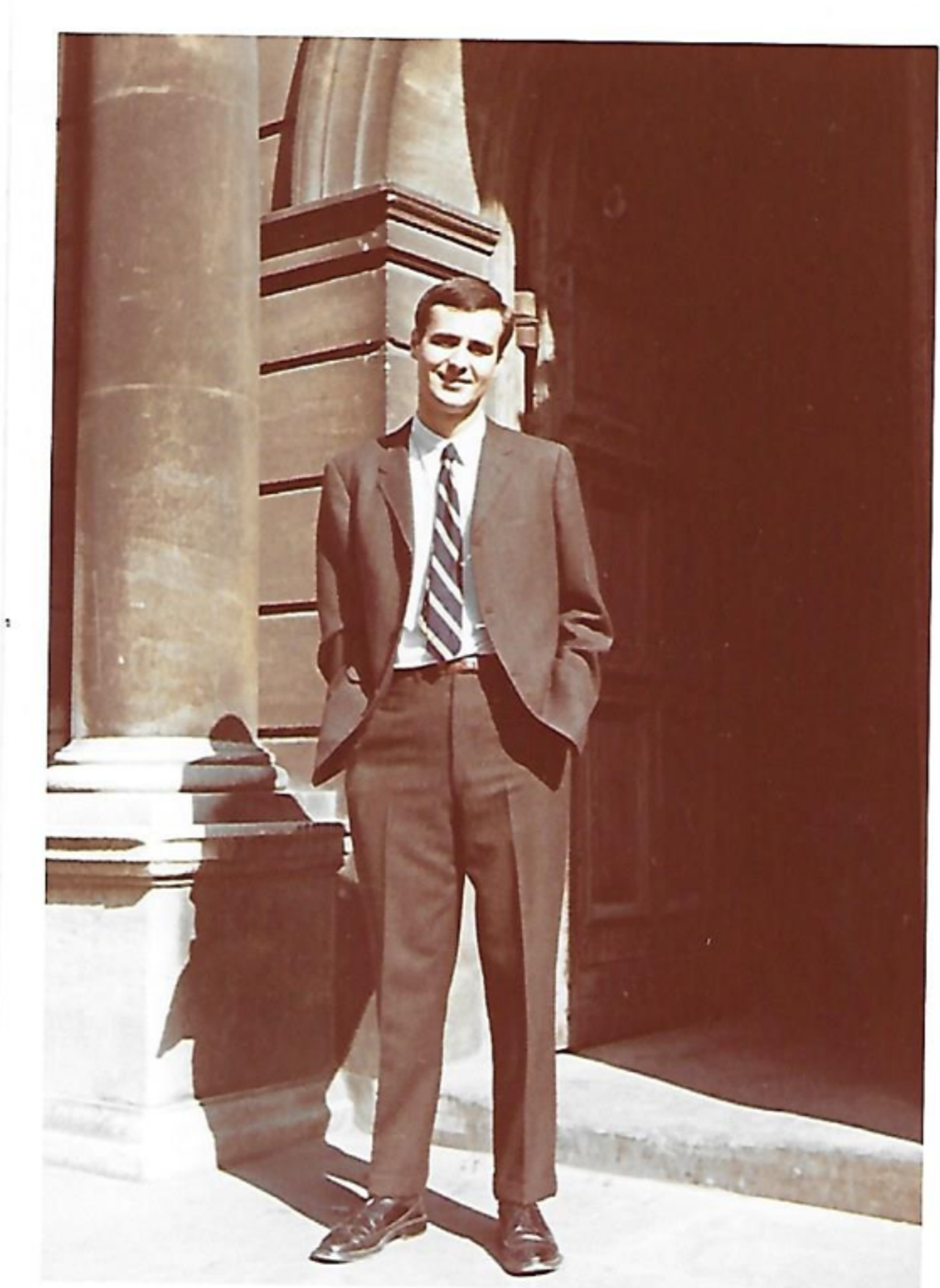

James O'Toole

California & Hertford 1966

‘I pretty much spent my youth in Golden Gate Park’

I grew up in the Richmond District of San Francisco, where I pretty much spent my youth in Golden Gate Park. In high school, I ran the entire length of the park every day, and during my spare time I was in the de Young Museum and the California Academy of Sciences, which were free to enter then. My father was an uneducated labourer who had dropped out of school when he was 14 or 15. My mother finished high school and worked most of her life as a secretary at Temple Emanu-El. I briefly worked there and was lucky to have several rabbis give me good advice when it came to choosing colleges.

I went to a very good public high school and had dreams of attending Stanford. My father had suggested I travel to Europe the summer before college, which I did, and while there, I learned that Stanford had rejected me. I was a track athlete, so when I returned, I went to see the Stanford coach to ask for advice, and he suggested I head down to USC where the coach offered me a scholarship. The only problem was, he offered the scholarship on a Friday, and school started on Monday, so I had exactly one weekend to drive back 420 miles to San Francisco, pack up my stuff, and then head back down to Los Angeles. But I did it, and USC was where I got serious about my studies. While there, my best friend and I started a tutorial programme in Watts that organised 500 USC undergrads to go into the black communities to help kids who were struggling in school. I’m proud that programme has continued ever since.

On applying for the Rhodes Scholarship

USC offered a summer programme where students could spend six weeks in the UK at Cambridge University, and I was one of the scholarship students chosen. I loved the dons, loved living in college, loved the ambience, and loved the pubs! When I returned to USC, my advisor suggested I should apply for the Rhodes Scholarship. I’d never even thought about that and was pretty relaxed in the first round of interviews because I felt I didn’t stand a chance. But when I got into the final round, I was much more nervous. I was selected, nonetheless. Aristotle tells us that one of the keys to happiness in life is good luck. I believe that to be the case, and I got lucky many times in my life.

I started off at Oxford reading for a B.A. in English, but I struggled with Anglo Saxon. I’d had a couple of courses in anthropology at USC and had been an assistant to a sociologist who was doing research in the African American community. So, I went to the Rhodes professor of race relations at Oxford, who was a South African, and told him I wanted to do a comparison of what I’d learned in Los Angeles to similar communities in South Africa, and he was intrigued. I then managed to convince the Warden to let me switch to a DPhil, and then got deeper into the study of social anthropology.

Between my first and second years, I married Marilyn Burrill, and worked during the summer for TIME magazine in Los Angeles. It was during a period of rioting and white TIME correspondents were afraid to go into black areas. I wasn’t, because I knew people there from the tutorial programme. So, I was able to interview people, and thus make a contribution, even as an untrained journalist.

My wife returned to Oxford with me, and we went directly on to South Africa. My idea was to do a comparison of Soweto and Watts, but the white South African authorities weren’t going to allow that. Then a professor at Witwatersrand University in Johannesburg suggested that I go to Cape Town, because the parallels between what was happening in Cape Town and what was happening in Los Angeles were close at that time. That turned out to be a great experience: building relationships with people in non-white Cape Town communities.

One of the things that occupied my time at Oxford was the Vietnam War. All the American scholars there spent hours discussing it. Our meetings were contentious at times, but eventually, a group of us wrote to President Johnson protesting the War, and our letter was printed on the front page of the New York Times.

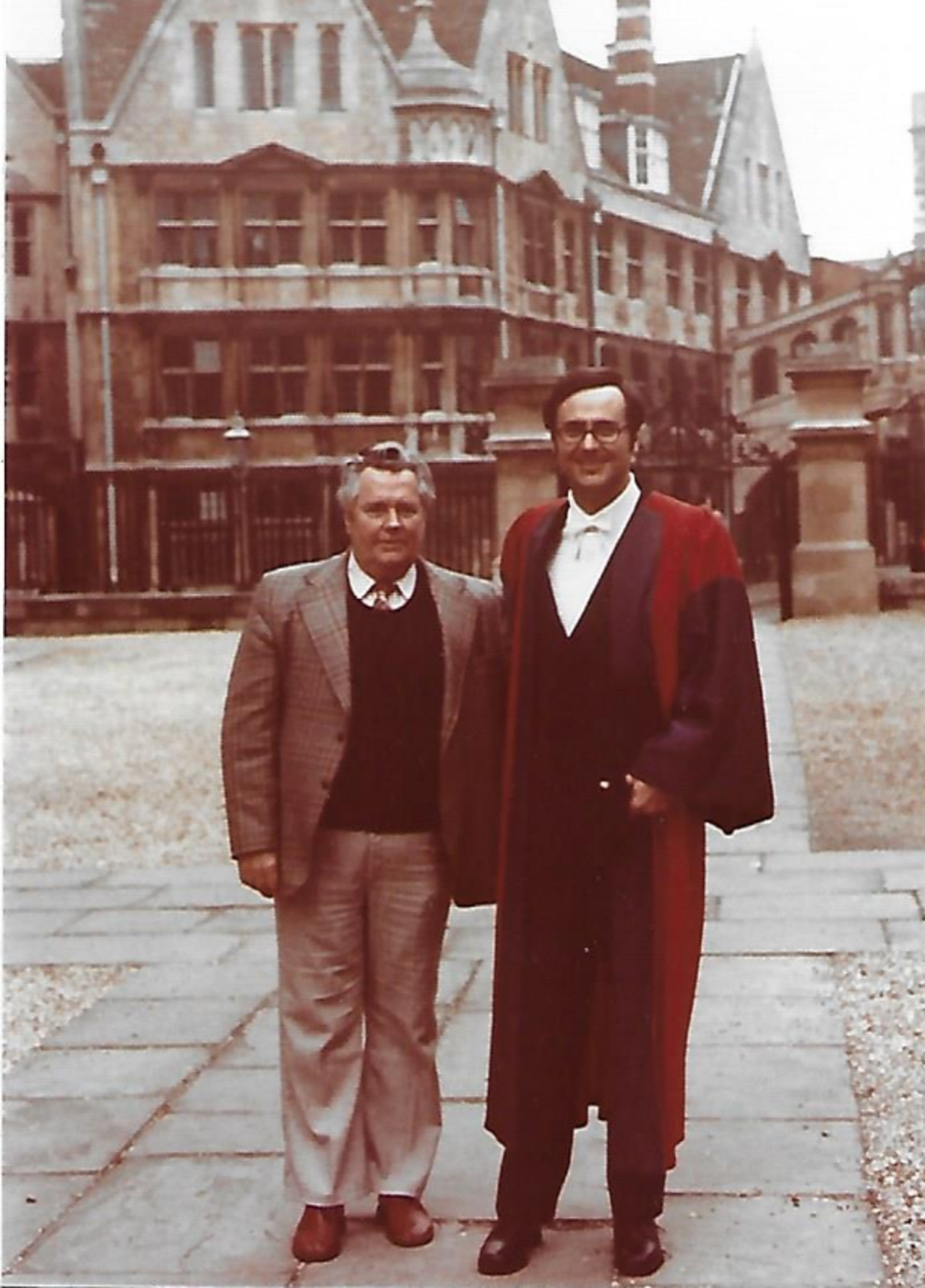

I worked for McKinsey for a period, and then finished writing my DPhil thesis. After I passed my viva, a friend in Washington, DC told me the Nixon administration was looking for someone to work on the President’s Commission on Campus Unrest (after the shootings at Kent State University). So, I took up a position, and stayed on later in Washington to work as a Special Assistant to Elliot Richardson, the Secretary of Health, Education and Welfare. That was where I had the idea for the research project on Work in America. It got a lot of publicity – both good and bad – and on the strength of it, I was offered a position at the Aspen Institute, which I accepted when it became clear that things were turning bad for the Nixon administration as the Watergate scandal developed.

‘The most important two weeks I ever spent anywhere’

While I was at the Aspen Institute, I was lucky enough to meet Mortimer Adler and to attend his two-week executive seminar. Mortimer assigned readings – Plato, Aristotle, Hobbes, Locke – and I had never read any of them. I realised that no matter what had happened at Oxford or at USC, my education really began at that point. By providing the fundamentals and the background of the Great Ideas, Mortimer helped me to build a foundation under all that I’d previously learned. That was probably the most important two weeks I ever spent anywhere.

Later, the Aspen Institute asked me to lead their seminar programme, and that work led me to write The Executive’s Compass. I also accepted a faculty position at USC. The teaching I did at the Aspen Institute and at USC is something I’m extremely proud of. I worked with executives of some of the largest corporations, helping them to understand what motivates people and how they should involve workers in decision making and profit sharing. At USC, Warren Bennis and I started New Management magazine, which became the inspiration for Inc. We had a considerable influence on the field of management during that period. Here I should add that all of my work has been a result of putting together great teams. I’ve always tried to surround myself with people who are better than me, and to closely work with them. I think that’s the best way to learn: from other people.

‘After you get it, you can work to deserve it’

My Rhodes classmates and I have become quite close. During the pandemic, we started having Zoom calls together, and we now hold online seminars, taking advantage of our diverse backgrounds to educate ourselves. I find I’m always still learning, and I’m also still working to try to make a difference. At the moment, that means doing what I can to help the city of San Francisco, which is going through an especially tough time following the pandemic.

I’ve talked to many of my classmates about the impact the Rhodes Scholarship has had on our lives, and we pretty much agree with something a member of my selection committee said: ‘There are only two truly significant things that have happened to me: When I won the Rhodes Scholarship, and when I got married.’ I think being given a Rhodes Scholarship means that you assume a responsibility to try to lead your life in a productive way. That means thinking about what it means to fight the world’s fight. I would say that most of us who have been given the Scholarship thought we didn’t deserve it, but then, after you get it, you can work to deserve it. I’ve tried my entire working life to deserve that honour.