Born in 1944 in Melbourne, Australia, Jaynie Anderson studied at the University of Melbourne and at Bryn Mawr College before coming to Oxford as the first woman Rhodes Visiting Fellow. After a period in Oxford as a lecturer in the university, at the Ruskin School of Drawing and Fine Art, she returned to Australia where she took up the Herald Chair of Fine Art at the University of Melbourne, holding the post until 2014. In 1999, Anderson was elected a Fellow of the Australian Academy of the Humanities. In 2008 she was elected president of CIHA (the Comité International d’Histoire de l’Art) and in 2009 she was appointed foundation Director of the Australian Institute of Art History. Anderson is now Professor Emerita at the University of Melbourne. Her publications include Giorgione: The Painter of Poetic Brevity, Crossing Cultures: Conflict, Migration and Convergence and The Cambridge Companion to Australian Art. This narrative is excerpted from an interview with the Rhodes Trust on 4 October 2024.

Jaynie Anderson

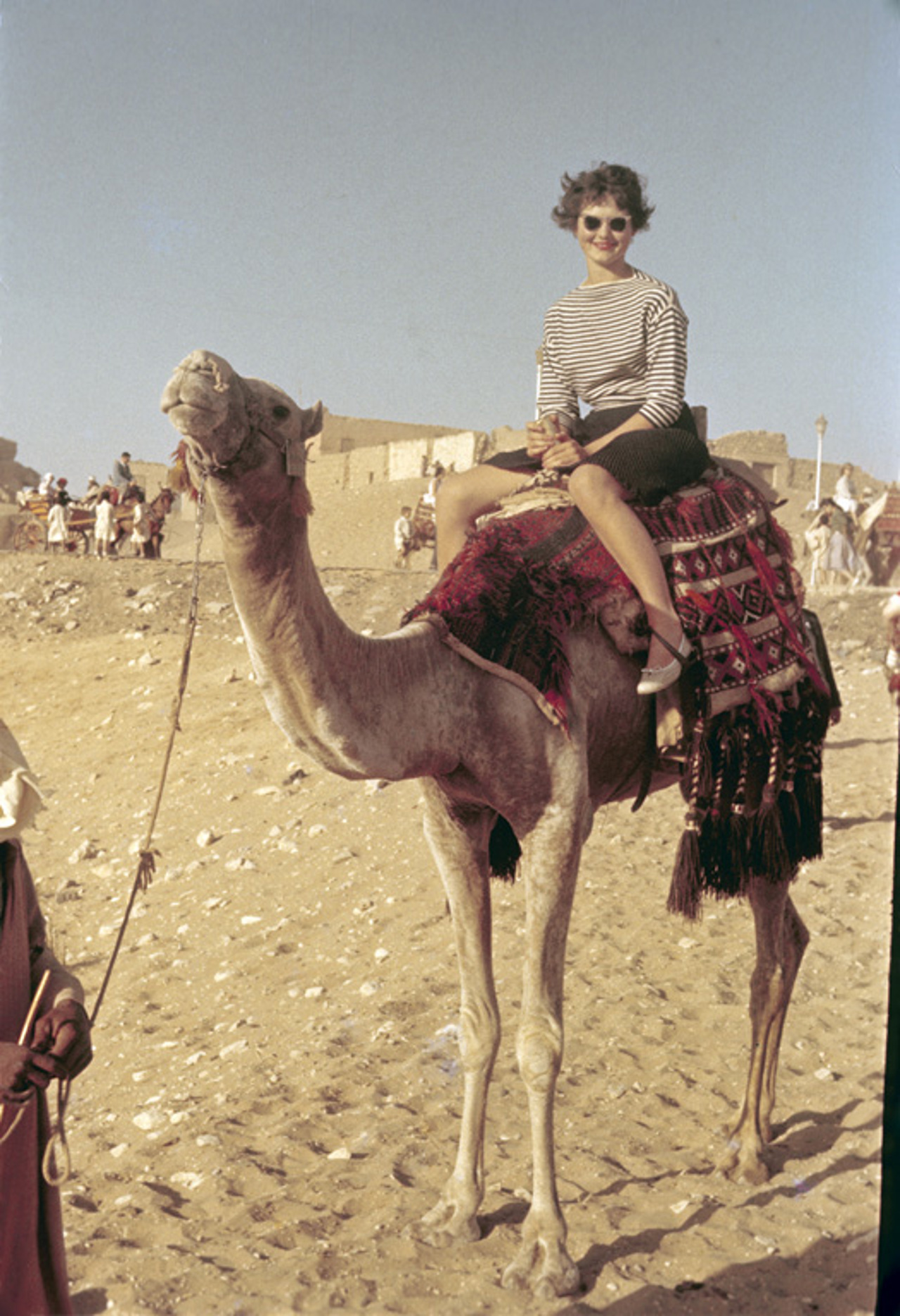

Rhodes Visiting Fellow & St Hugh’s 1970

‘I was enraptured with Venetian art’

I grew up in St Kilda, Melbourne, and although Australia in the 1940s and 1950s was much more isolated than it is today, St Kilda was a place where I witnessed the positive growth of multiculturalism. My father was a doctor, a general practitioner, and St Kilda was a Jewish suburb, so, he had a lot of Jewish patients. He also looked after people who came out to Australia from the prison camps in Germany on a famous boat called the Dunera. My father’s practice was in the house and we lived above it, so we were very aware of his patients, and many of them were immigrants who had come to the country after the Second World War. My mother was a musician who had gone to the Melbourne Conservatorium very young, as a prodigy. When I was five, she contracted polio. Until that time, my mother had been a brilliant personality, performing on the radio and everything, and after that, she was disabled. That was a a shock, and I became really quite competent, because I used to help her with everything.

Melbourne University was situated in an Italian quarter, and I grew up loving everything Italian, especially movies. We were a family of Anglicans; I went to a Church of England school and being there gave me a lifelong interest in religious imagery. I used to go out and buy sacred postcards at the sacristy shop nearby. So, that was a quite important thing for me to be acquainted with, fairly early on. I also went abroad with my parents when I was young. We went to Japan, and that was when I first discovered the art of another culture. The next year, we went to Europe, and we arrived one morning as the sun rose on the Bay of Naples. It was very magical and romantic and I was hooked from that moment. We went to Venice, where I saw Giorgione’s Tempesta for the first time. I was enraptured with Venetian art, and I’ve spent a lot of my life studying it.

On applying for the Rhodes Visiting Fellowship

I was going to read history at university, but then I went to an arts fair and discovered that there was this subject called art history, so I did a joint degree in history and art history. I went to the University of Melbourne for my undergraduate studies, and I was very lucky, because we had excellent teachers. Again, the impact of people who came from abroad after the Second World War was very apparent. In art history, the professor was Joseph Burke, and we also had Franz Philipp, who taught the Renaissance, who was from Vienna, and Bernard Smith, was the first Australian art historian. It was an exciting period. I wasn’t much good at university to start with, but in the end, I did manage to get a first.

I had begun to write art reviews for the university newspaper and then, I was invited to go to the US, to Bryn Mawr. That was a wonderful experience. It was very cheap to travel around and every weekend, we’d go to the theatre and to art galleries. I gradually came to terms with all these American collections and that was quite important for my later development. I went on and had a fellowship at the Warburg in London and eventually, I went to Oxford as the first woman Rhodes Visiting Fellow.

‘Concentrated excellence’

It was terrific being in Oxford. The impact it had on you was one of concentrated excellence in different fields, and always being around that was rather wonderful. You would continually meet people of great intelligence and excellence, and that doesn’t always happen everywhere. I remember going to a seminar about heraldry, and to another about drawing where there were original works of art for us to look at. Socially, Oxford was a bit stiff at times, compared with the freedom I’d known in Australia, but there was so much academic excellence that that didn’t matter.

I was examined for the Rhodes Visiting Fellowship by Edgar Wind, who was the first professor of art history in Oxford. And it wasn’t like an exam, really. It was just like the most wonderful experience of talking about your subject and it went on for hours and I didn’t want it to stop. The art history department at Oxford at that time was very small, and the professor, Francis Haskell, wasn’t very interested in Renaissance art and didn’t really like what I was doing on Giorgione. He was very discouraging, and overtly misogynist, and he said to me, ‘You have to be at least over 60 to write on Giorgione, and it won’t be an Australian woman who does it.’

“This is the way art history should be written” (French critic Philipe Dagen on the front page of Le Monde)

Despite that discouragement, I published articles from my thesis which were quite successful, and I was invited to Italy to lecture on Giorgione. I was very good at finding archival material that no one else had found before, so, I published on that, and then a French publisher rang me and asked if I wanted to do a book on Giorgione. I agreed, but only if it could also be published in English, and it still remains the major work on Giorgione.

When I came back to Australia, I decided to work on different things for a time. I did the Cambridge Companion to Australian Art and I also convened an international congress on art history in 2008 which was about the multicultural experience of Australia. It was the first truly international art history conference. Being in Australia gave me the freedom to do that kind of work and also to teach as I wanted to teach, designing new curricula. I’ve especially enjoyed working on Australian indigenous material and seeing how indigenous work has emerged as the equal of anything else in the world. Australian First Nations art is the oldest in the world, with pieces that can be dated back to 60,000 BC. I’d go and look at these works of art, and they are often in beautiful but very inaccessible places. It’s wonderful to see the continuity of that tradition.

Now, I’ve just completed another book on Giorgione, working with the Vatican conservation laboratory. That came about because just after I’d retired, I got a call from Sydney University Library and they said they’d discovered a drawing on the last page of a book of Dante’s Divine Comedy, and also an inscription about Giorgione. I went up and authenticated it and published a piece in the Burlington Magazine. When it was published, a lot of newspapers picked up the story. It’s the book I’m probably most proud of having done. I tried to write it in a style that was very fresh and engaging, and I think I succeeded. I was especially proud of the review in Le Monde des Livres, which said, ‘This is the way art history should be written.’

I’m also about to write a memoir of my life. And my current project is a book on Sidney Nolan. I think he’s a great artist and still underestimated, even though he’s very famous. When you get to be 80, you wonder how long you’ve got, so, you’ve got to get on with things. But I still get a thrill just out of looking at art and going to a gallery and talking about it. It’s just like I’m I kid again, when I was 15 and going to Venice. I just love works of art.

‘Be ambitious’

I learned an awful lot at Oxford and the impact of the Rhodes Visiting Fellowship on my life was tremendous. But for all that, I was painfully shy when I was at Oxford, and so, when someone told me I’d got something wrong, I would believe it. Having taught a lot of women and men, I do think that men don’t worry as much when they get criticism back. They just throw it off. But as a rule, women don’t. However much you tell them not to worry, criticism hangs on to them. If I had my life over again, I would hope to be more confident and not be put off. So, my advice to today’s Rhodes Scholars is to be ambitious. Try, and if people knock you back, just ignore them!