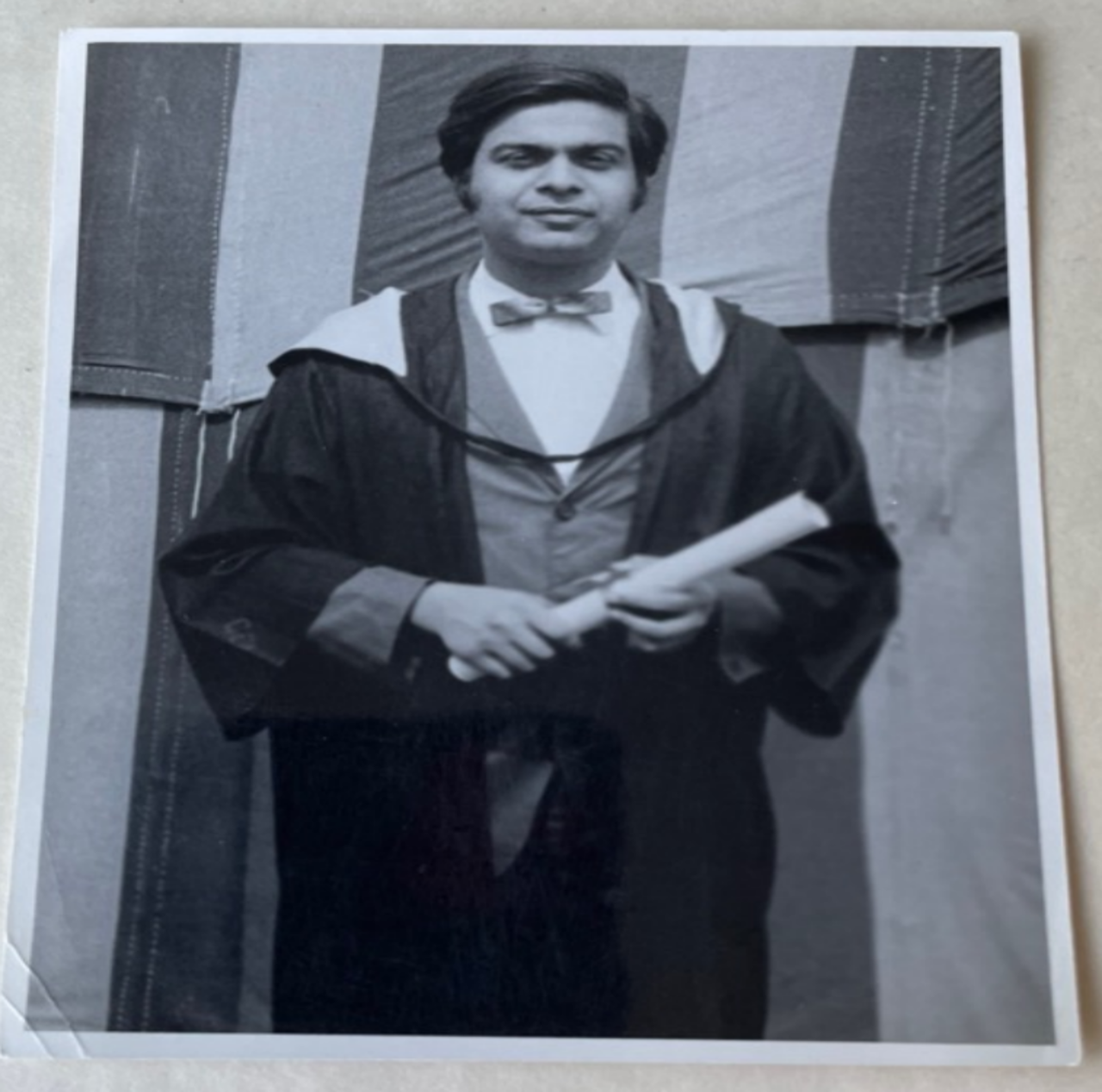

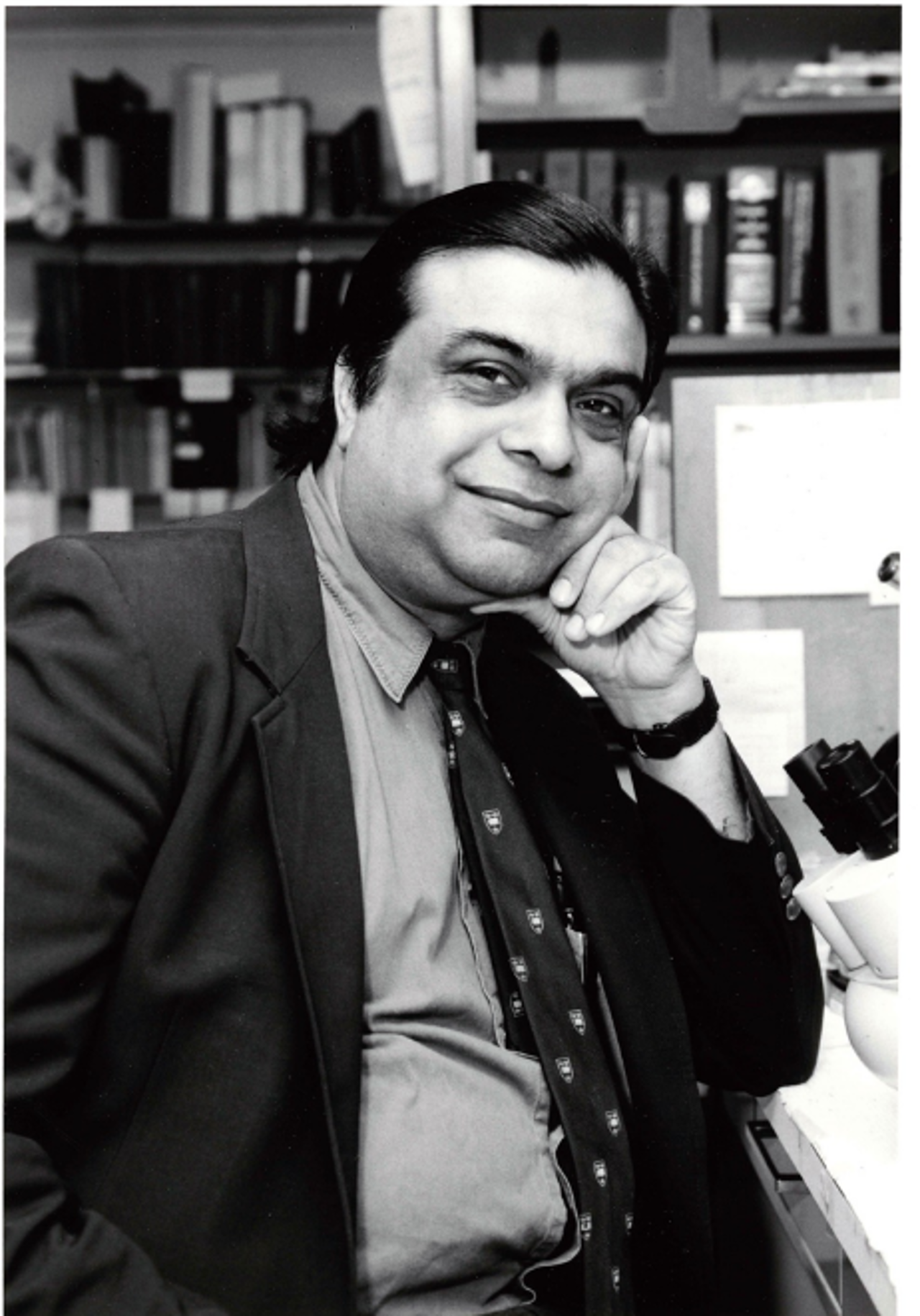

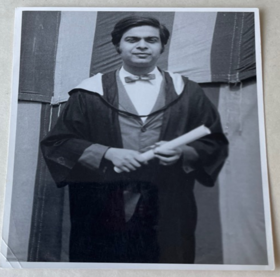

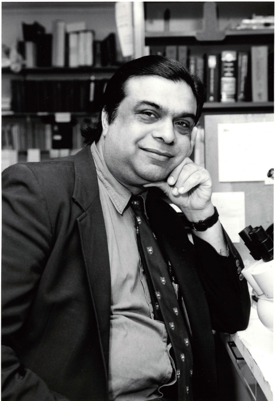

Born in Kolkata in 1946, Jahar Bhattacharya studied at the All India Institute of Medical Sciences, New Delhi, before coming to Oxford to take a D.Phil. in the physiology sciences. He went on to complete his postdoctoral training at the Cardiovascular Research Institute, University of California at San Francisco and is now Professor of Medicine and Professor of Physiology & Cellular Biophysics at the Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons, Columbia University Irving Medical Center (CUIMC) and also Director of Lung Research at the Division of Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine, CUIMC. His research into the biology of acute lung injury has received multiple NIH grants and his many awards include the MERIT award of NIH, the Julius Comroe award of the American Physiological Society, and the Amberson Award of the American Thoracic Society. This narrative is excerpted from an interview with the Rhodes Trust on 12 June 2024.

Jahar Bhattacharya

India & Christ Church 1970

“White Cliffs of Dover, I’m coming back!”

I was born in the city of Kolkata, although when I was born, it was called Calcutta, the anglicised version of the name. I had a rough beginning, because I was born prematurely. These were times when there were no incubators or specialist care facilities in Kolkata. My mother had a horrible experience during my birth, but she managed to keep me hydrated and get me to eat, and that saved my life. Like a lot of premature kids, I was left with bronchial asthma, so although I loved and played sports, I couldn’t really participate in the high activity parts. I did a lot of debating and theatre, and when I was 12, I started learning the violin, which became a passion in my life.

My earliest education was actually in England. I’d accompanied my parents to Westcliff-on-Sea in Essex. I loved the local school and I still remember that time with great fondness. When we left, we took the ferry and my mum turned me around and said, ‘Look, those are the White Cliffs of Dover.’ I said to myself, ‘White Cliffs of Dover, I’m coming back!’

On applying for the Rhodes Scholarship

After finishing high school in India, I went directly into medical school, the All India Institute of Medical Sciences, which had only just been created. The professors were newly recruited and excited about their mission, and I had a great time there. I have to say I also loved it because the classrooms were air-conditioned, and because it was close enough to my family home that I could go back for lunch and dinner! I was lucky enough to meet my wife, Sunita, while I was studying there. I always tell people we met over a dead body, though the story works better if I don’t explain that it was in the dissection class of the Human Anatomy course. Very soon, Sunita was coming home with me for lunches and dinners too.

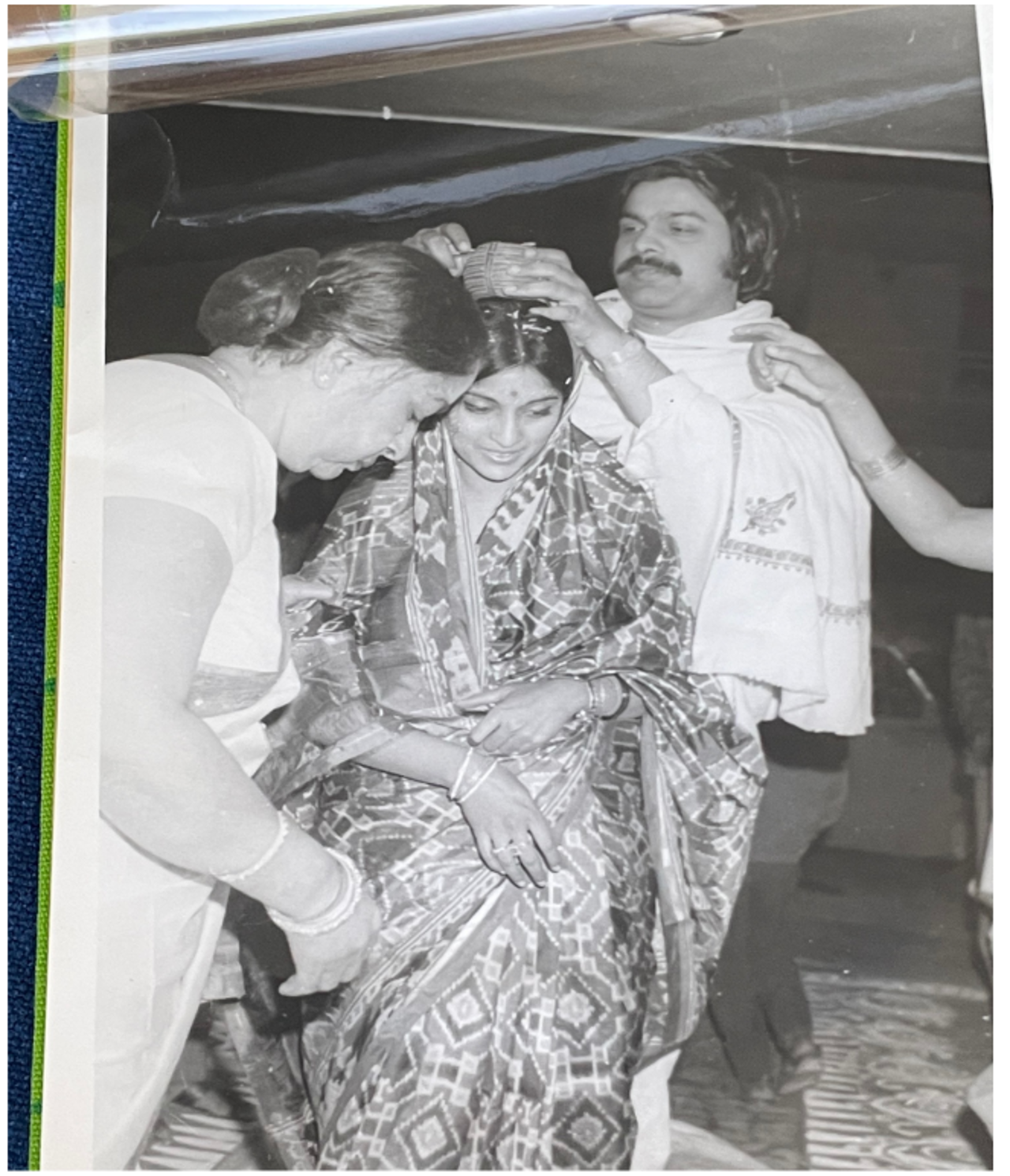

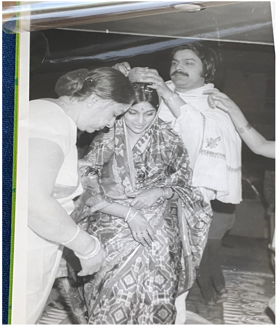

While I was studying, I saw this little ad for the Rhodes Scholarship. I didn’t know much about it, except that two people ahead of me in my medical school had successfully applied. I had always been interested in the idea of having a scientific career rather than only practising clinical medicine, and it became evident to me that if I go selected for the Rhodes I’d have a different track than most doctors. Leaving India didn’t feel especially dramatic, although Sunita and I have a rather poignant photo of me on the day I left: my mother’s face is that of a mum who is about to lose her son to a big trip abroad.

‘You could enlarge your experience just by a conversation’

At Oxford, I joined the department of physiology. I wanted to study the physiology of the lungs, but there was no one working directly on that who could supervise my research. So, I joined a lab that was working on the control of breathing, and I did a master’s there and then later switched to another project. I have to say that at that time, the Rhodes Scholarship wasn’t very well set up for people who wanted to read for a D.Phil.. Things are different now, but then, I had to find my own path to develop the subject matter for my doctoral thesis.

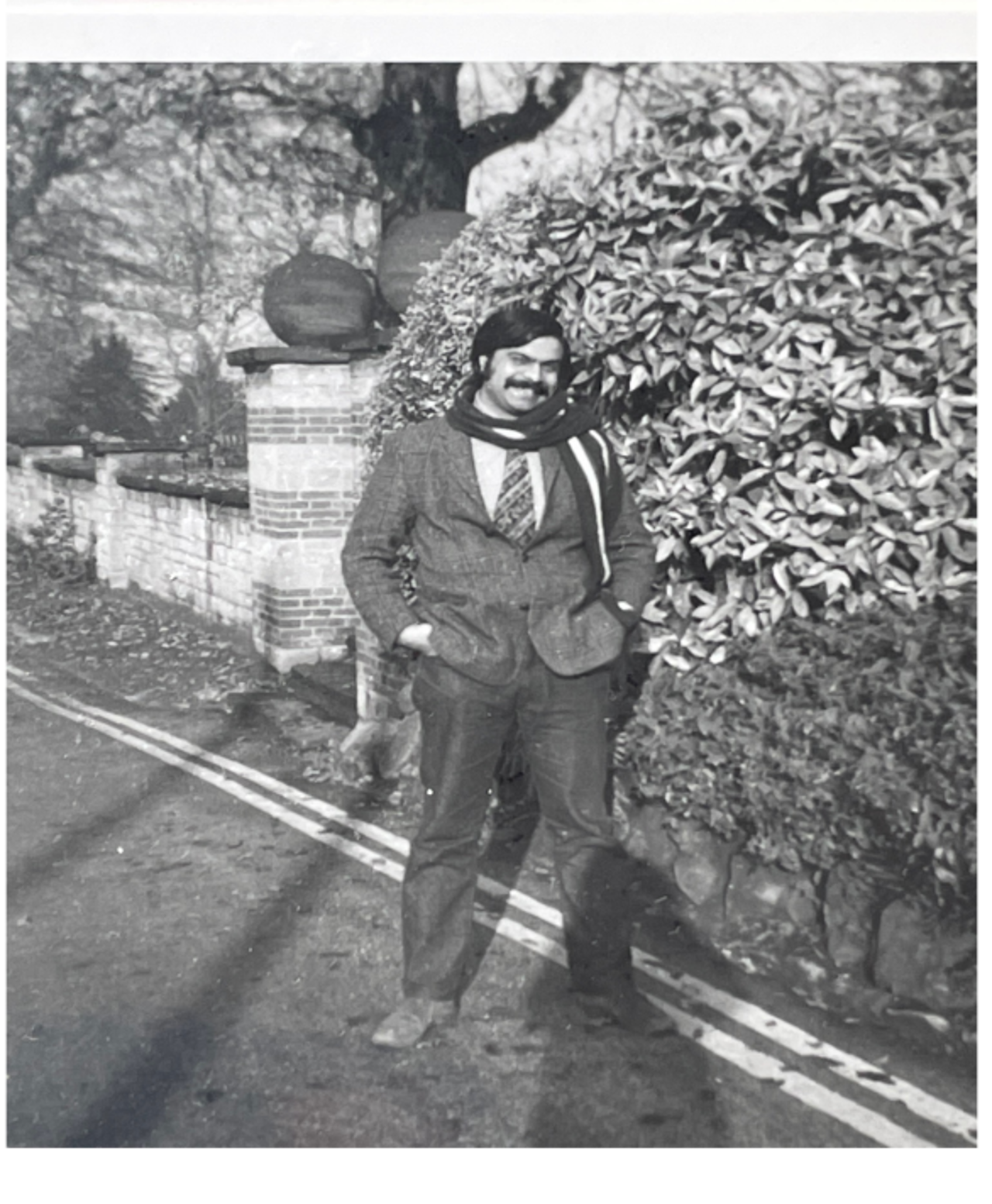

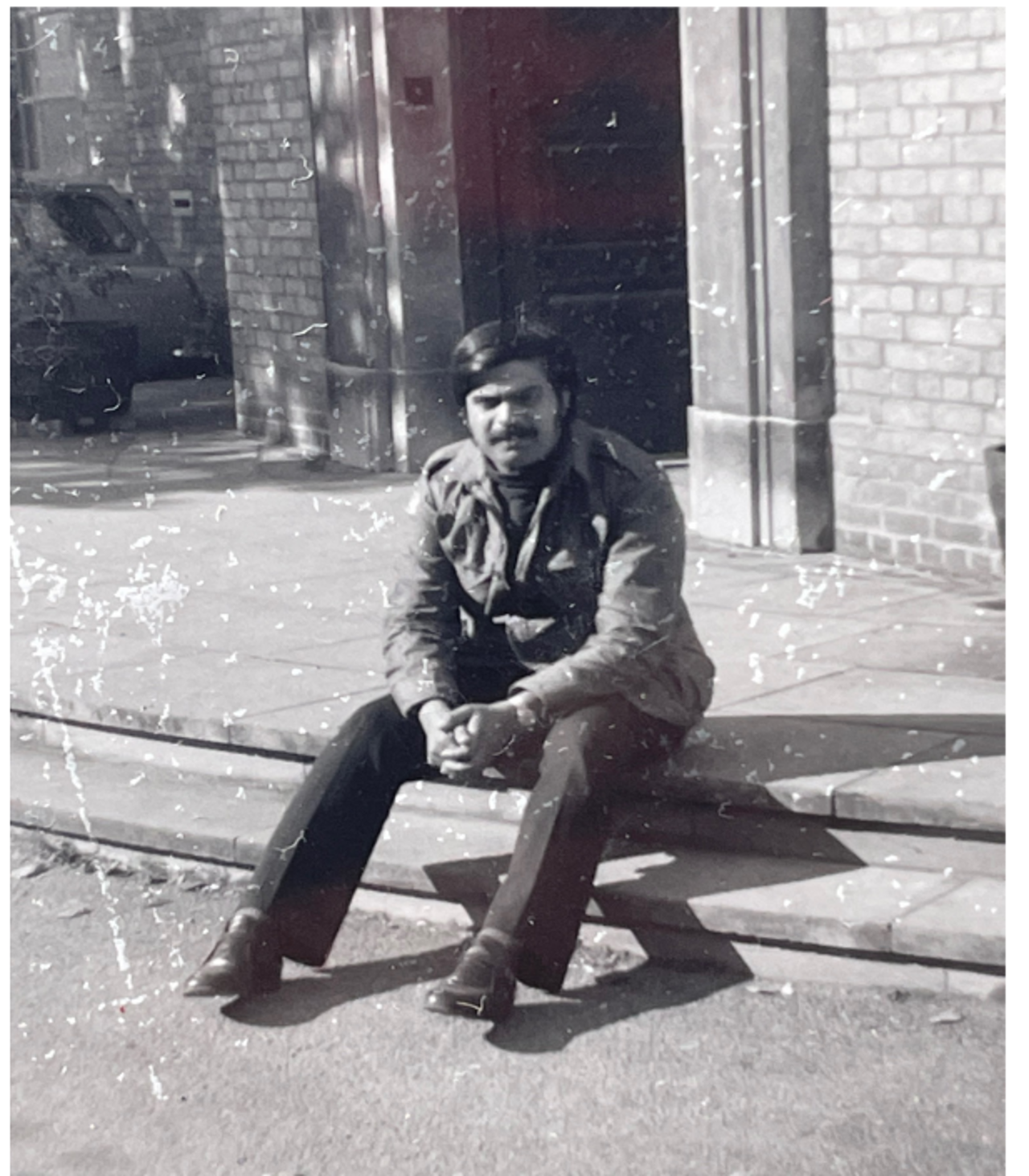

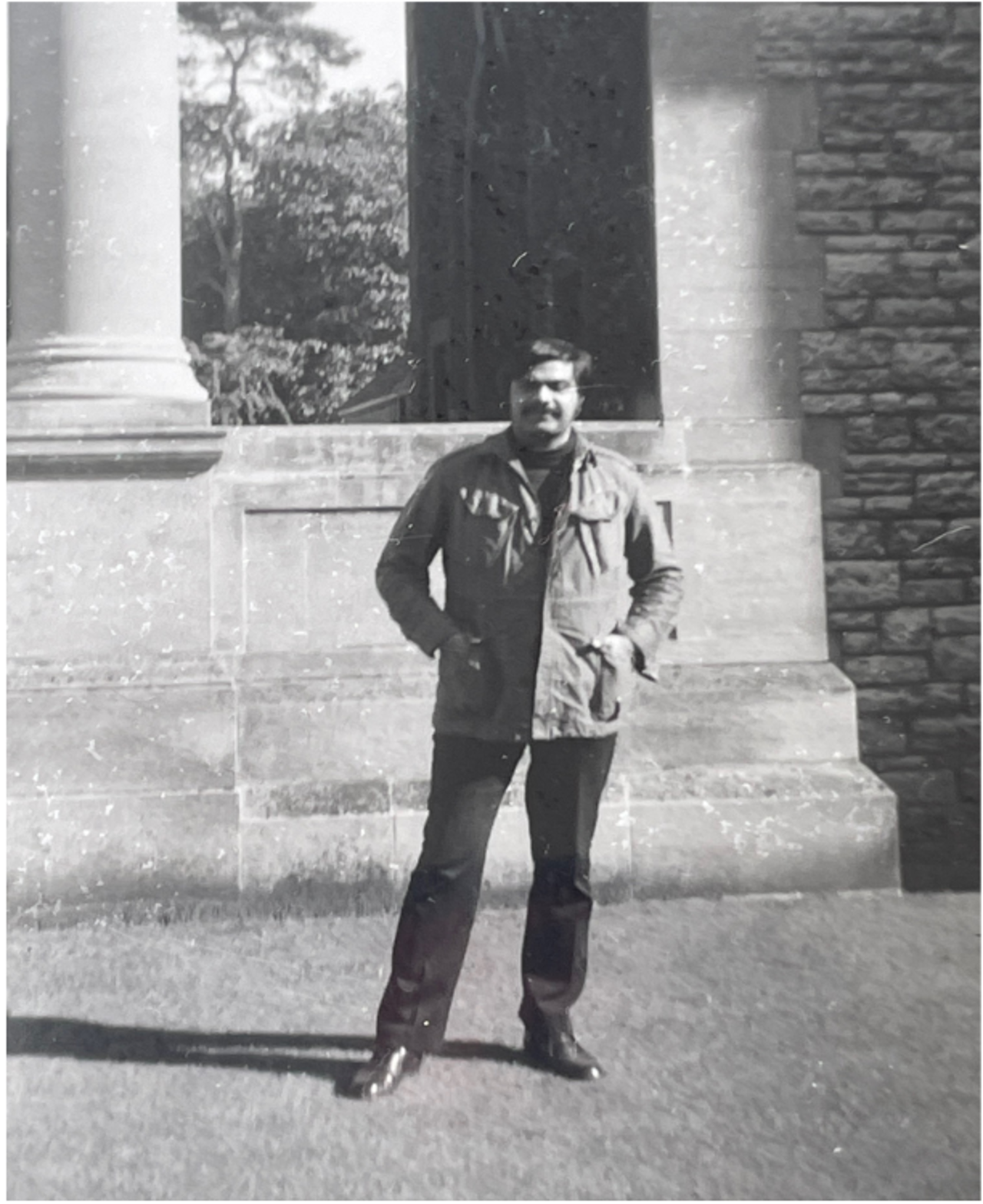

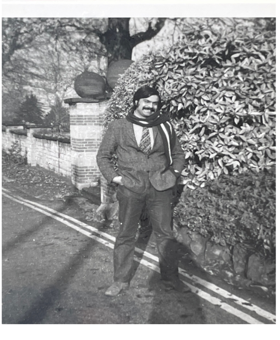

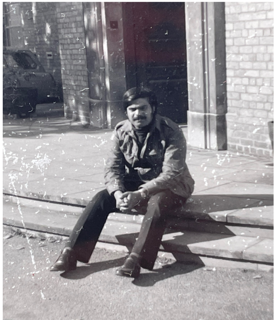

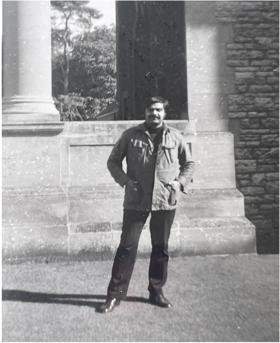

I lived in college accommodation for the first year. These were the days when you still had what they called a scout to look after you, and even to polish your shoes if you wanted. I found that very odd, but I was in a realm of new experiences. We had to wear our academic gowns to dinner, and the Graduate Common Room there had an honours system where you could sign a chit for sherry or whatever you wanted for pre-dinner drinks. Christ Church really spoiled us. It was a very different experience when I had to find private accommodation the following year. But the chance to meet so many new people was exciting, and I made friends with many of the American Rhodes Scholars and also with the other Indian Rhodes Scholars, who were almost all historians and working on the history of Modern India, especially the political movement under the influence of Gandhi. Knowing them and learning more about that was extremely enjoyable and fulfilling.

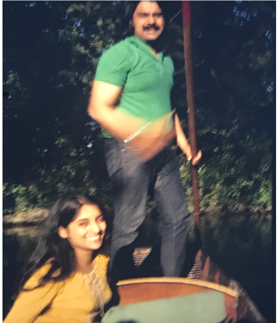

Sunita and I were engaged by this time, but the rule was that Rhodes Scholars were not allowed to marry in the first year. So, we got married during my second year. By then, Sunita was doing medical work in the US, but eventually, she was able to join me in the UK, although she was working in Nottingham rather than Oxford. Our lives were in a state of flux, professionally. I was struggling with deciding what kind of research to do, and Sunita was trying to work out whether to go for just clinical medicine or to combine that with research. I had a little car, and I would drive up to Nottingham to see her. It was a delightful drive going up there, but a painful one coming back. We had a brief period together when Sunita got a job at the Churchill Hospital in Oxford. We were both reading all kinds of things, seeing movies, and meeting people who were incredibly interesting, and who could enlarge your experience just by a conversation. At the same time, I was studying with a fantastic music teacher, learning about western music, and this was the time when I changed from playing violin to playing viola. Being in Oxford together, exploring all these new things, was a truly sparkling experience.

‘Asking the difficult question is the job of all of us’

I would say that my intellectual page was turned in Oxford. Seeing the giants of academia openly disagreeing with one another, understanding that the goal was to establish a novel line of thinking, I thought that was so cool. It made me realise that asking the difficult question is the job of all of us. And that whole attitude of questioning was further honed when I moved to the US and took up a postdoctoral post in San Francisco at the Cardiovascular Research Institute. I was lucky enough to work with a phenomenal scientist who was known for his lung research, and that’s where I really developed my interest in pulmonary edema, learning about the complexity of the disease. It’s a fascinating field.

Sunita’s research was in this same area, although coming from the neonatal end. But things were much more difficult for her professionally at that time. Because of the timing of my first postdoctoral position in the US, I had to leave Oxford before she did, and she was pregnant with our first child. Our first son was born in Oxford, and Sunita came out with our baby to join me in the US shortly afterwards. Unfortunately, that meant breaking off her own research work in Oxford. When we were in San Francisco, it was great that we were all able to be together, but times were tough financially. Sunita took on clinical work to help us make ends meet, and without that, I don’t think we could have made it.

When I was looking for permanent posts, I had a number of offers, but we chose New York because we were interested in spending some time there. The idea was just to be in New York for a few years and then move back to an Indian university, as we were both quite eager to return home and be close to our parents. But we stayed on in New York, and our two sons grew up here. Sunita has now retired from clinical work, and I am semi-retired as well. We continue our collaboration, though, with me still in the lab and Sunita reading the relevant literature and discussing the science with me. We have been so fortunate to be able to work together like this for over 35 years now.

‘Learn about Oxford’

Going to Oxford changed my life and gave me new perspectives. The Rhodes Scholarship is a great opportunity, and I would encourage today’s Scholars to take every advantage of what Oxford has to give. In my day, Rhodes House didn’t offer that much by way of advice or networking for people wanting to read for a D.Phil. in the sciences. But I know that things are changing now. Nonetheless, I think it’s important for Scholars to do as much research about Oxford as they can before they arrive. If you’re doing a D.Phil., in particular, it’s important to find out about your department and the people who might act as mentors to you. Look at the options available and, if possible, make contact with a few of those people you might want to study with. Develop those vital relationships. Learn about Oxford. That way, you can have the best possible idea of how to position yourself once you arrive.