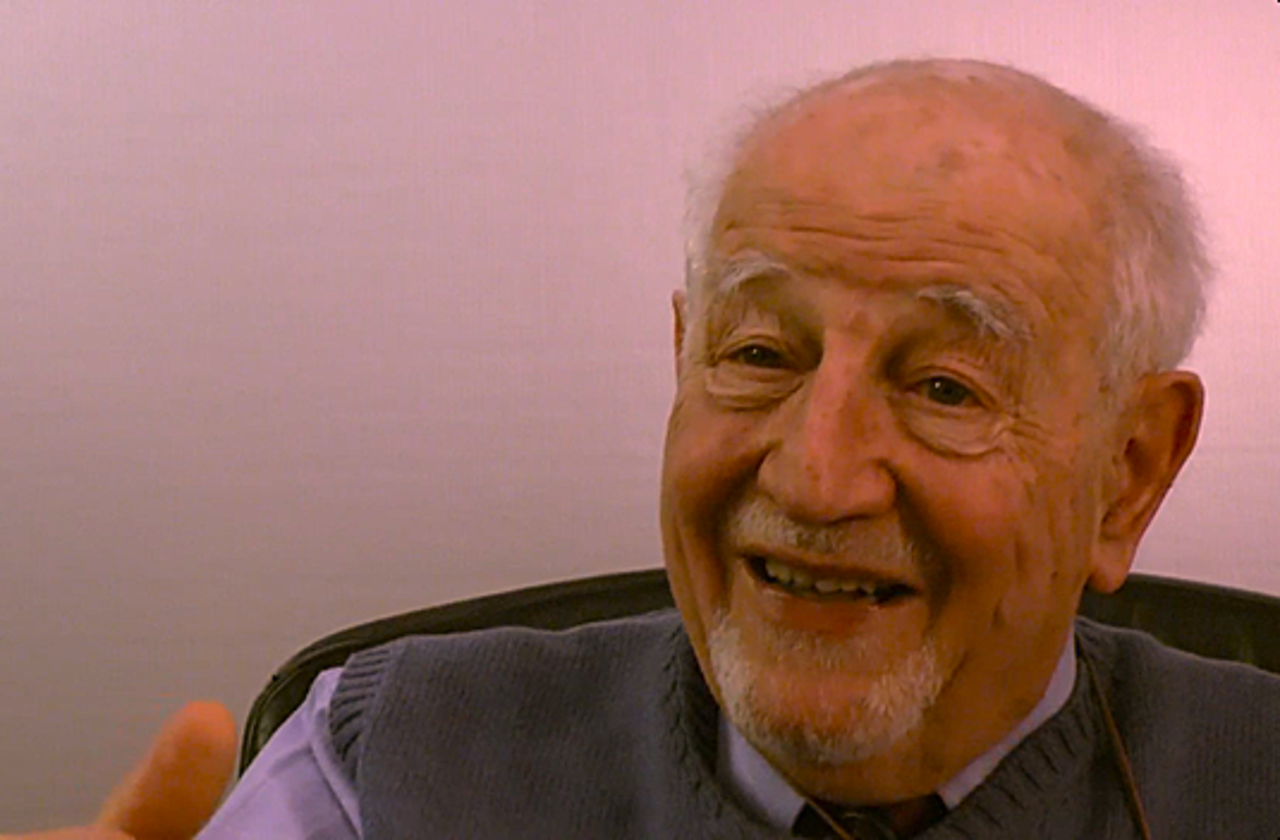

Born in Milan, Guido Calabresi fled Italy for the US with his family in the 1930s. After majoring in economics at Yale, he read PPE at Oxford and began teaching economics at Yale while also attending Yale Law School. He served as Dean and Sterling Professor at Yale Law School and was appointed United States Circuit Judge in 1994. He is the author of seven books and over 100 articles on law and cognate subjects. This narrative is excerpted from an interview with the Rhodes Trust on 22 January, 2024.

Guido Calabresi

Connecticut & Magdalen 1953

‘You weren’t really allowed to leave a dictatorship’

We lived in Italy until I was almost seven. We left primarily because we were anti-fascists. It also happened that at the same time, the country passed racial laws, and many of my ancestors are Italian Jewish. We were able to get out because some people in the US had managed to give some money to Yale to invite my father to take up a fellowship. You weren’t really allowed to leave a dictatorship, but you could go for a term. We were very lucky.

When we moved to New Haven, I went to a very good public school and then later, a terrific little private school in New Haven offered me a scholarship. The school was extraordinary, and it was extraordinary because of Yale’s bigotry at that time. Yale did not have women teachers, so many of the extremely able wives and daughters of the professors taught in my school. I went on to Hopkins School, and from there to Yale. At first, I thought I would do math, and then I considered history. And then I thought, history and math together, why not economics?

On applying for the Rhodes Scholarship

I was encouraged to apply for the Rhodes Scholarship by Tom Mendenhall (Wisconsin & Balliol 1933). When the selection committee asked about my time as a soccer captain for my college at Yale, I confessed that I had been made captain because of my organisation skills. After recruiting some really good players, therefore, the first thing I did was bench myself. The members of the committee laughed about that and thought it was a good thing.

I remember, too, being asked about a person I admired in public life, and when I said, ‘Dean Acheson,’ the chair of the committee asked whether I’d said that because I knew that one of the chair’s children was married to one of Acheson’s children. I think I may even have said, rather angrily, ‘How the hell should I?’ You know, how would somebody from Connecticut know about these Boston marriages? And they all burst out laughing. It was, by the way, the same committee that picked Ronnie Dworkin (Rhodes Island & Magdalen 1953). In many ways, he was the bright philosopher from Harvard and I was the bright economist from Yale.

‘Take chances’

I chose Magdalen because I wanted a college that was intellectually really good and that was also beautiful. I considered reading law, but eventually I decided that I wanted to study more philosophy than I’d been able to at Yale, and Oxford was at the peak of philosophy at that time. So, I read PPE. I had taken enough economics at Yale so they allowed me to essentially play at economics, doing advanced things that I wanted to do while doing basic things in philosophy and politics. Magdalen was strange, because at that time it was still in some ways very, very concerned with being snobbish. I wasn’t especially interested in that. The people I liked were those who were intellectually interesting, and often, they came from other countries. The sense that social class was absolute was one of the reasons I didn’t eventually stay in England, even though Magdalen offered me a fellowship.

For me, a significant moment that stands out in my time at Oxford was when I was called to my President’s collection at the end of my first term. One of my tutors said, ‘Mr Calabresi rarely makes a mistake. It would be better if he made a few more.’ And when I asked him what that meant, he said ‘You have two years. Take chances; try to fly. You might fall on your face, but if you ever get off the ground, you won’t be willing simply to walk.’ And I’d been working hard, but I’d been having an easy time. What he said was incredibly liberating and it’s moved me in what I’ve done and been part of my teaching and scholarship ever since.

‘A great dean is really a great butler’

I came back from Oxford to Yale Law School and I also started teaching economics to undergraduates in that same year. I had never had so much fun in my life, and I knew then that what I wanted to do was law and what I wanted to do was teach law. I was very lucky that I found both of those things right away. As a teacher, it’s up to you to help students either slow down or to speed up, depending on what they need. There are students who are so anxious to change the world that they don’t take the time to figure out how to do it, and there are some who are so concerned with doing well for themselves that you’ve got to broaden them and speed them up. Different classes from year to year will be different according to what’s going on in the outside world. Teachers have to respond to that to bring about what a place like Yale should do, which is to create leaders for a better society.

When I was asked to be dean of Yale Law School, I wasn’t sure about doing it. I loved teaching and I loved writing, but this was something very different. What I liked about it was that you couldn’t impose your views on others. A great dean is really a great butler, like Jeeves or the Admirable Crichton. The master of the house is the faculty and the students: your basic job is to see what the place is about and find the best way of doing it. You are also there to offer support. As dean, you are the one person anyone can go to with their problems, and your role is to love them and help them with their problems.

I hadn’t ever envisioned serving as a judge. And, when I was very young, I turned down an offer to be a federal district judge because I couldn’t do that and teach. Then, when President Clinton asked me to serve as a circuit judge of the Court of Appeals, I hesitated, because I wanted to finish my deanship. But when it came to it, I said, ‘I’m an immigrant, I’m a refugee and I’m a patriot. A critical patriot, but I am a patriot. If a president of the United States asks me to do something that I’m able to do and which is honourable, I would never say “No”.’

Being a judge and being a scholar and teacher do feed each other, although they are very different things. When people say to judges and lawmakers, ‘Do justice though the heavens fall,’ that’s nonsense. As a judge, you have to look at the immediate consequences of what you’re doing. You have to go slowly. Academics, though, can write and teach though the heavens fall, and must do that, because the heavens don’t fall. Their job is to tell the truth as they see it, and then be ignored for a time.

‘Do something in your life that is fun and useful, and never sell yourself short’

The advice my tutor gave me about taking risks has certainly helped me, not least in my scholarship. I’ve always thought that really interesting scholars are paradigm breakers. They look at the field and say, ‘What if we completely turn it around?’. That is the greatest fun of scholarship and if you can get your students to do the same, it’s also the greatest joy of teaching.

As a judge, I hope I can come up with decisions that make things better, at least in a small way. The thing that makes judging most challenging is that you’re bound to follow the law even when you disagree with it. But what do you do when the law seems deeply wrong? You wake up in the middle of the night and work at it and then you come up with something which is right in the law and right in a moral way and you take it to your fellow judges and say, ‘Look, I think we’ve looked at this all wrong. We can come out this way.’ And they say, ‘Guido, good. This case has been bothering me.’ And when you can do that, you sleep well the next night. That happened to me a few years ago in the only capital case I had, and because of what I found, the person’s death sentence was commuted.

I think the secret of a happy life is doing something which is fun and useful and having somebody to spend your life with. I’ve been very lucky in both and both still inspire me today. What I would say to today’s Rhodes Scholars is twofold: First, ‘Take chances.’ Second, ‘Never sell yourself short.’ Don’t do something in your life which isn’t fun and useful and doesn’t challenge you. And remember that excellence, which all of you have, is bad unless it’s combined with love and humanity. Excellence without humanity and love is awful.