Photo 1: Greg, 11, “up” on one of his Uncle Tommy’s beautiful cutting horses. It ties Greg to his Texas story, and especially to a legacy of country life extending back to years well before the American Civil War. It was his great grandfather Fayet Hicks, a cowboy, who learned of his emancipation only after the final Union victory in that war.

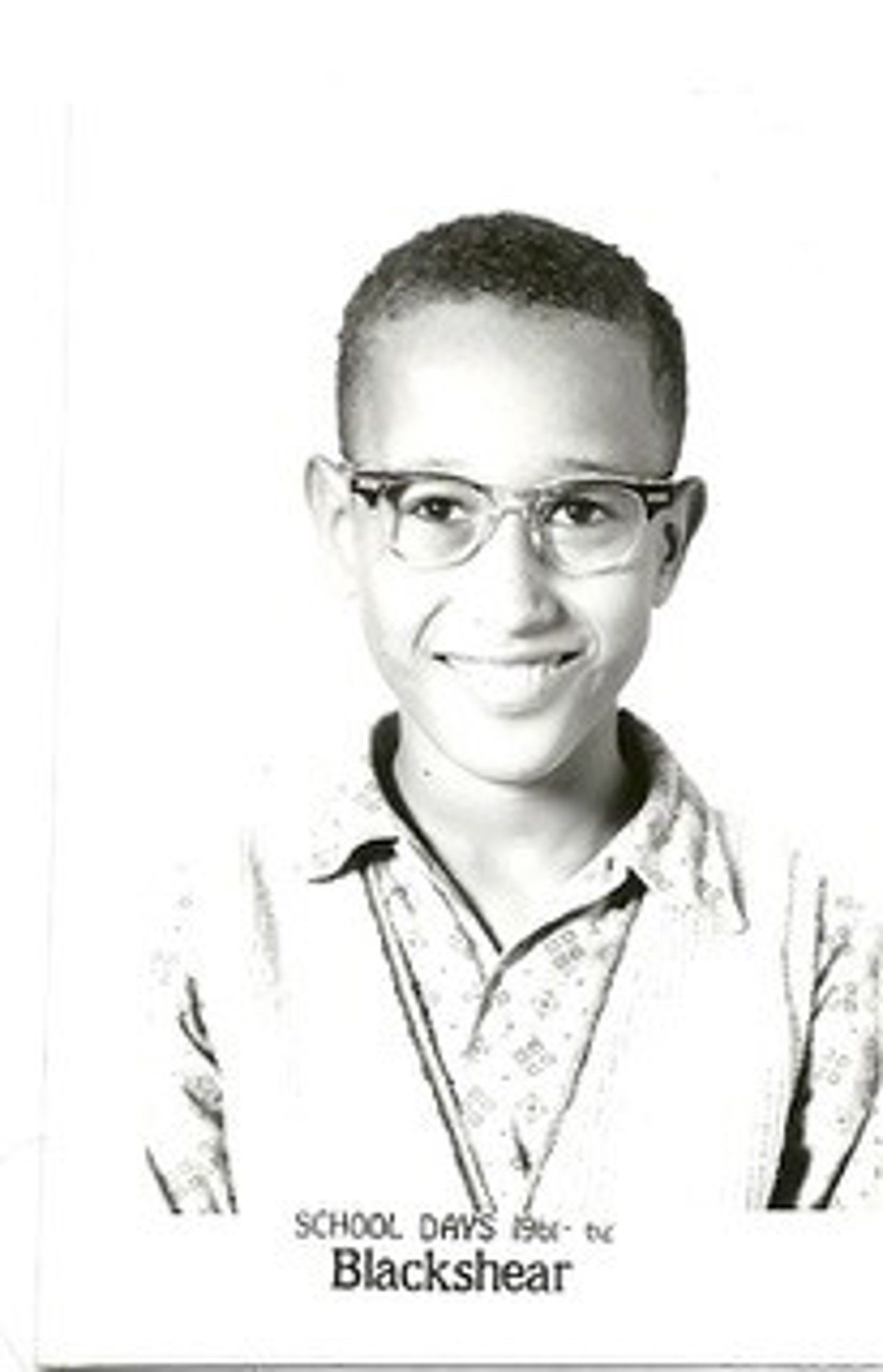

Photo 2: Another boyhood picture taken while Greg was a pupil at the then-segregated Blackshear Elementary School in Austin, Texas (further context below). He grew up quite in the middle of dramatic social changes in Texas and in the rest of the American South, and this picture is an artifact of that moment and also for capturing Greg's generally happy state of being in those years.

Born in Austin, Texas in 1950, Greg Hicks attended Yale before going to Oxford to study for a BPhil in comparative literature. After graduating from the University of Texas School of Law, he practised law and then took up a post at the University of Washington in Seattle. There, Hicks switched his area of focus to issues of water law, property law and history and public lands. He continues as Professor of Law at the University of Washington in Seattle and is involved in a range of projects across Spain, the US and South America, exploring natural resources and architecture. Hicks also serves on the boards of The Nature Conservancy of Washington and the Pacific Forest Trust and is an adviser to the Officer of the Washington State Attorney General on water law and policy matters. This narrative is excerpted and edited from an interview with the Rhodes Trust on 17 June 2024.