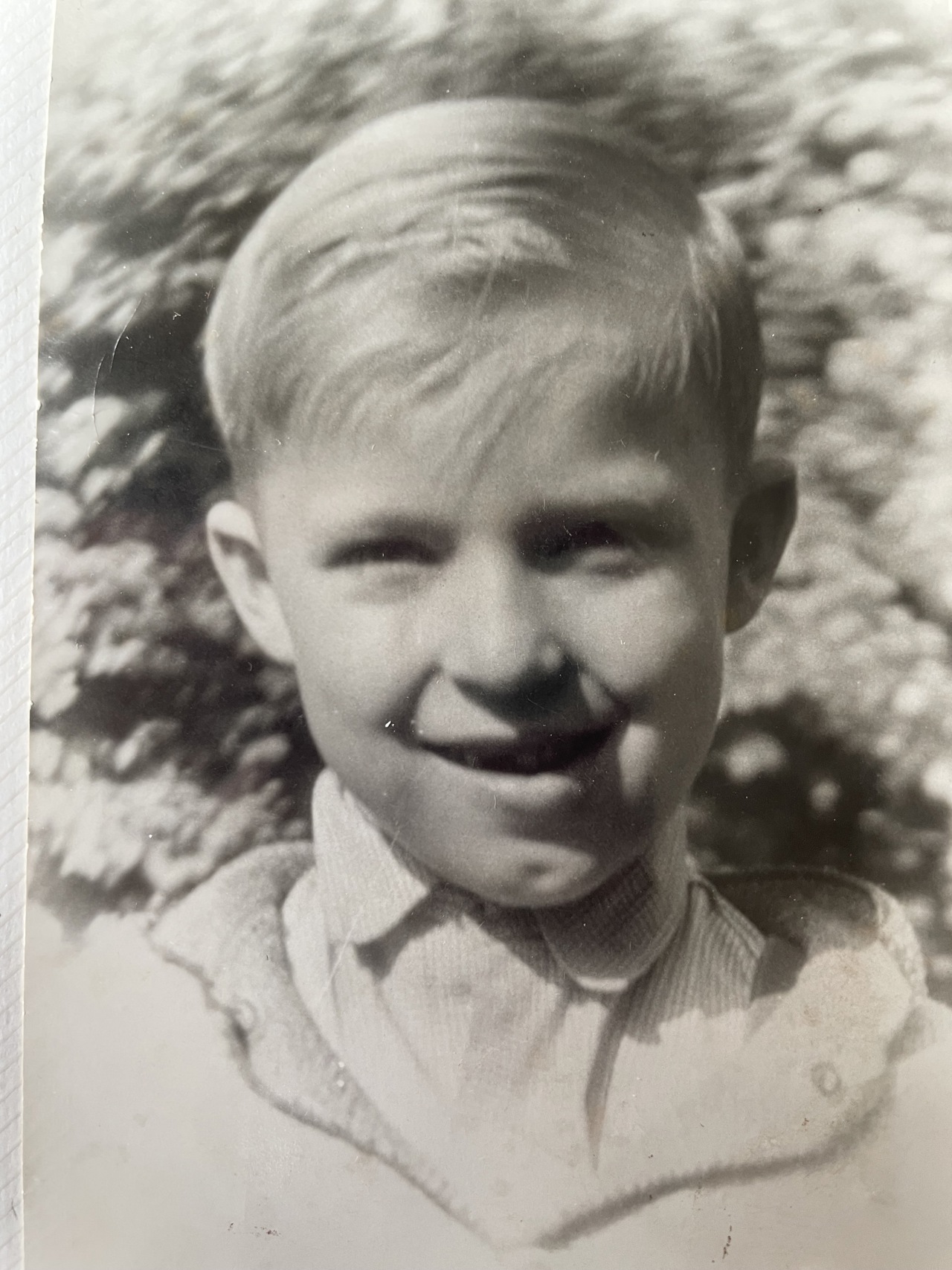

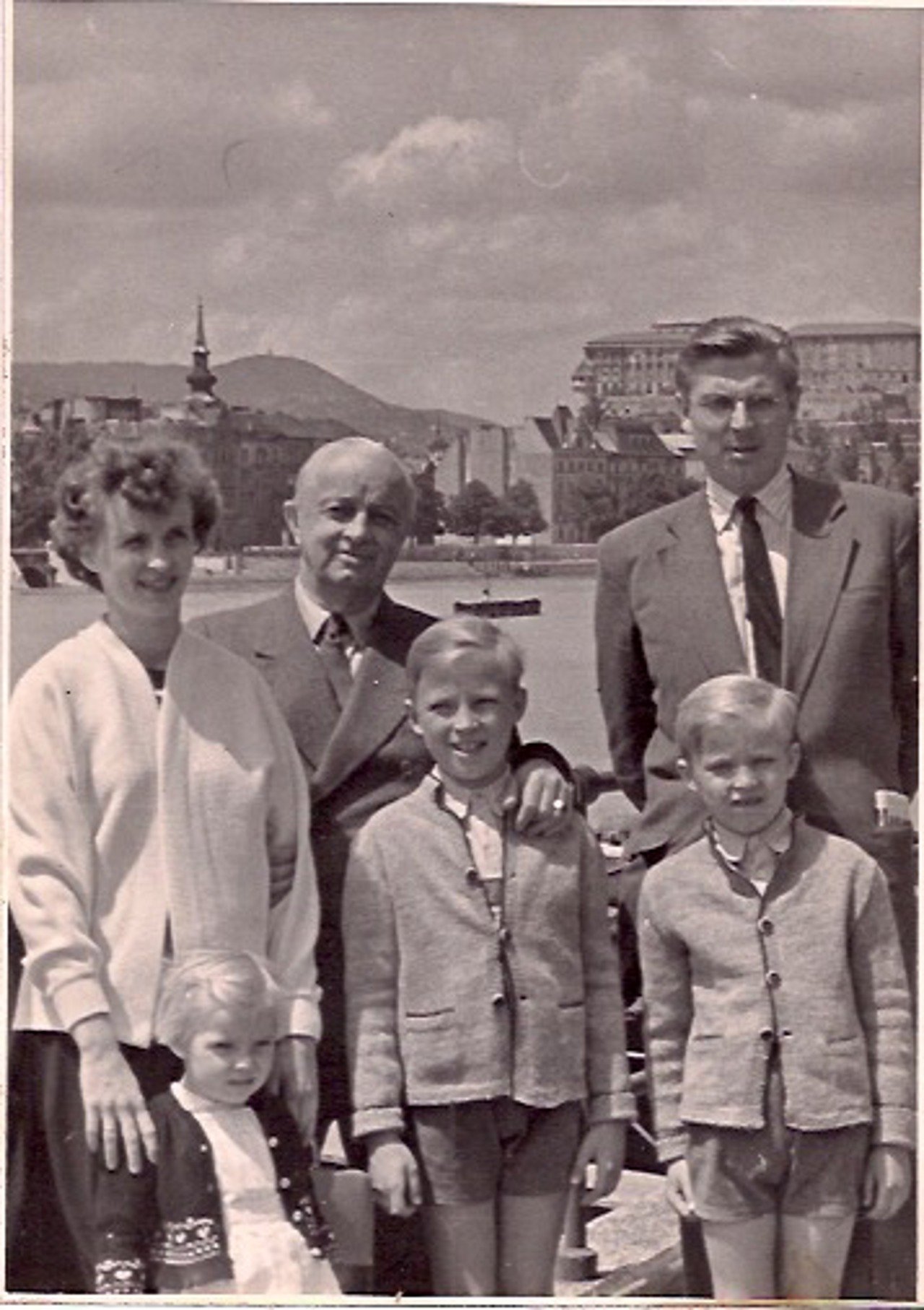

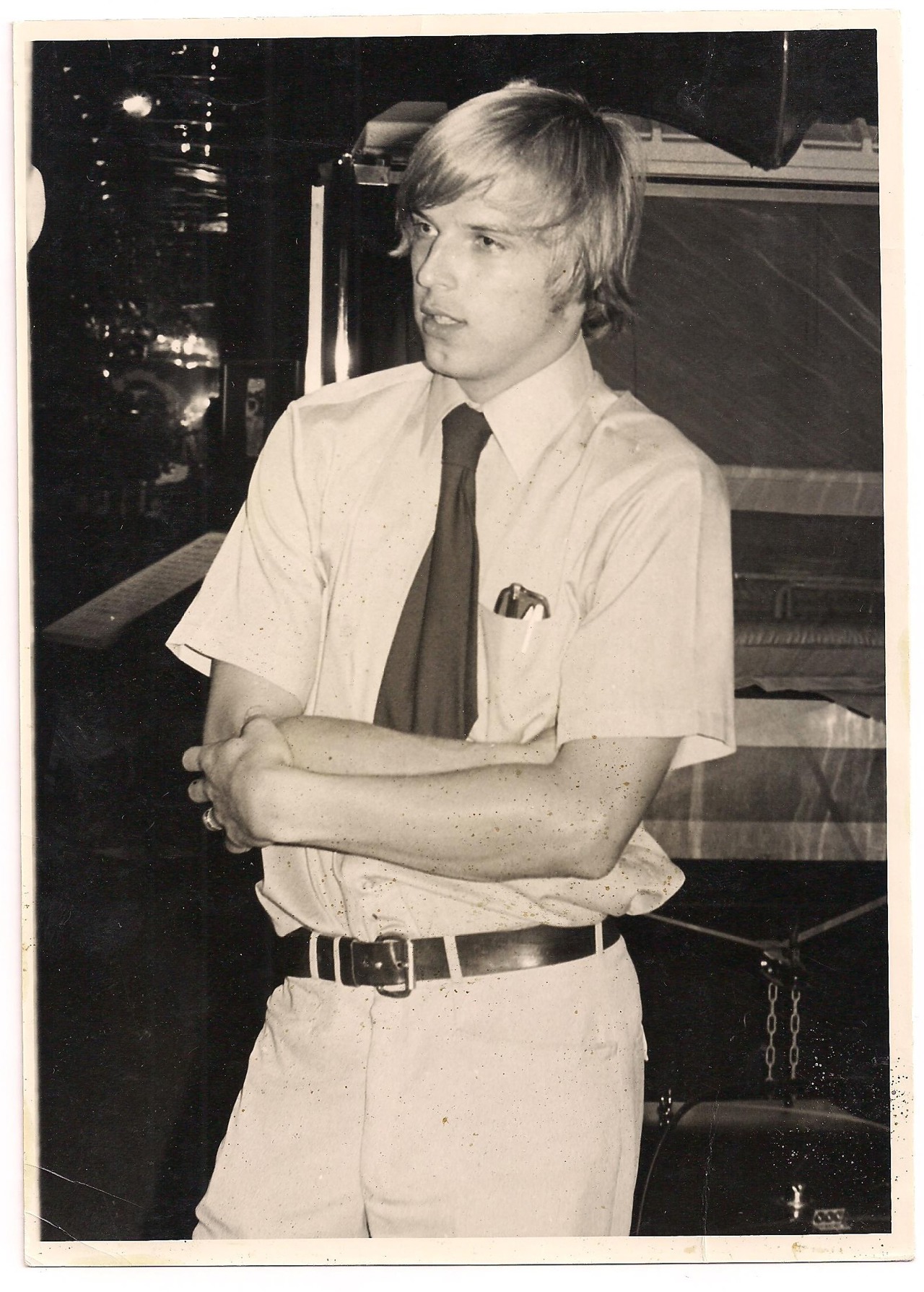

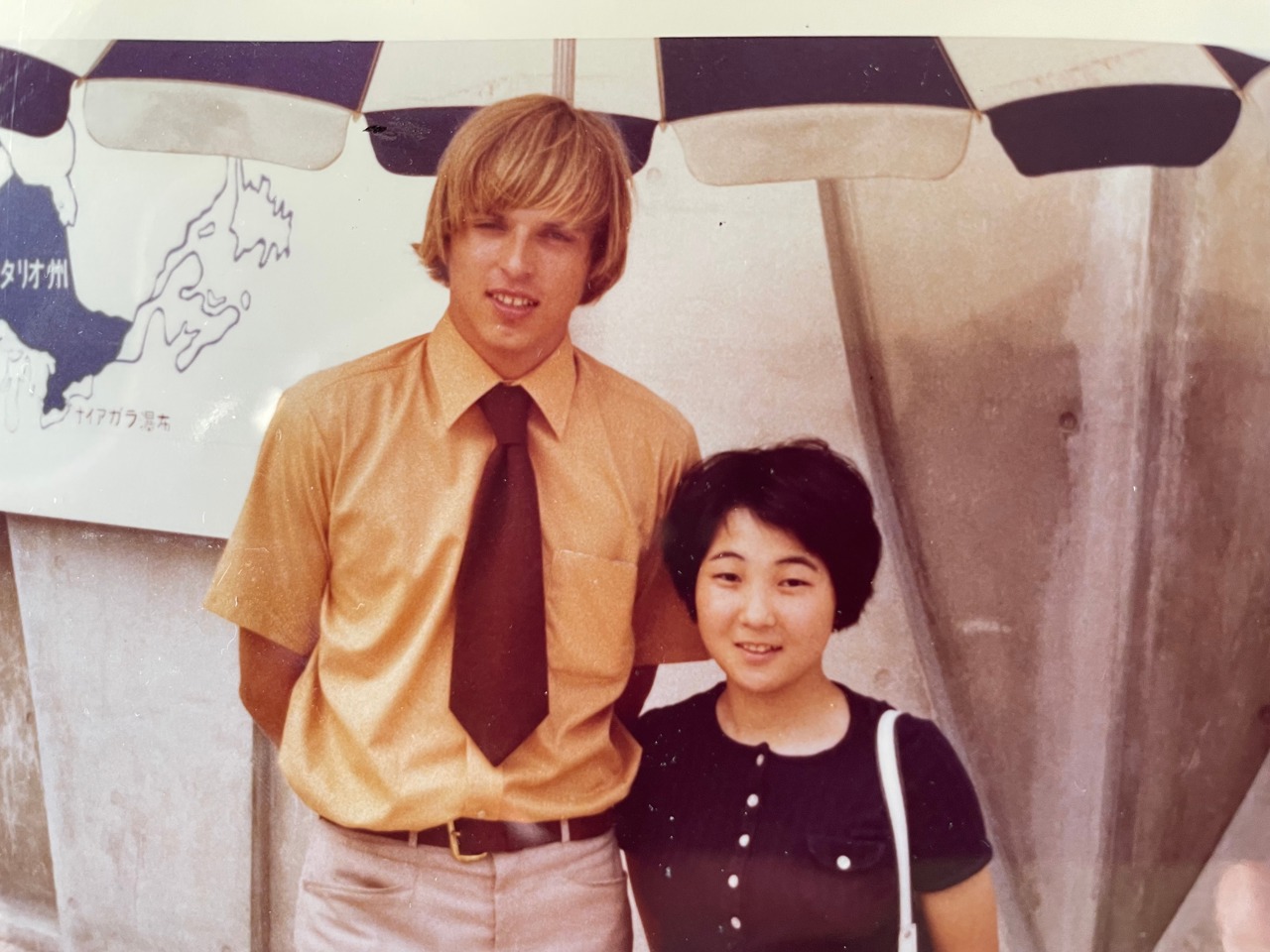

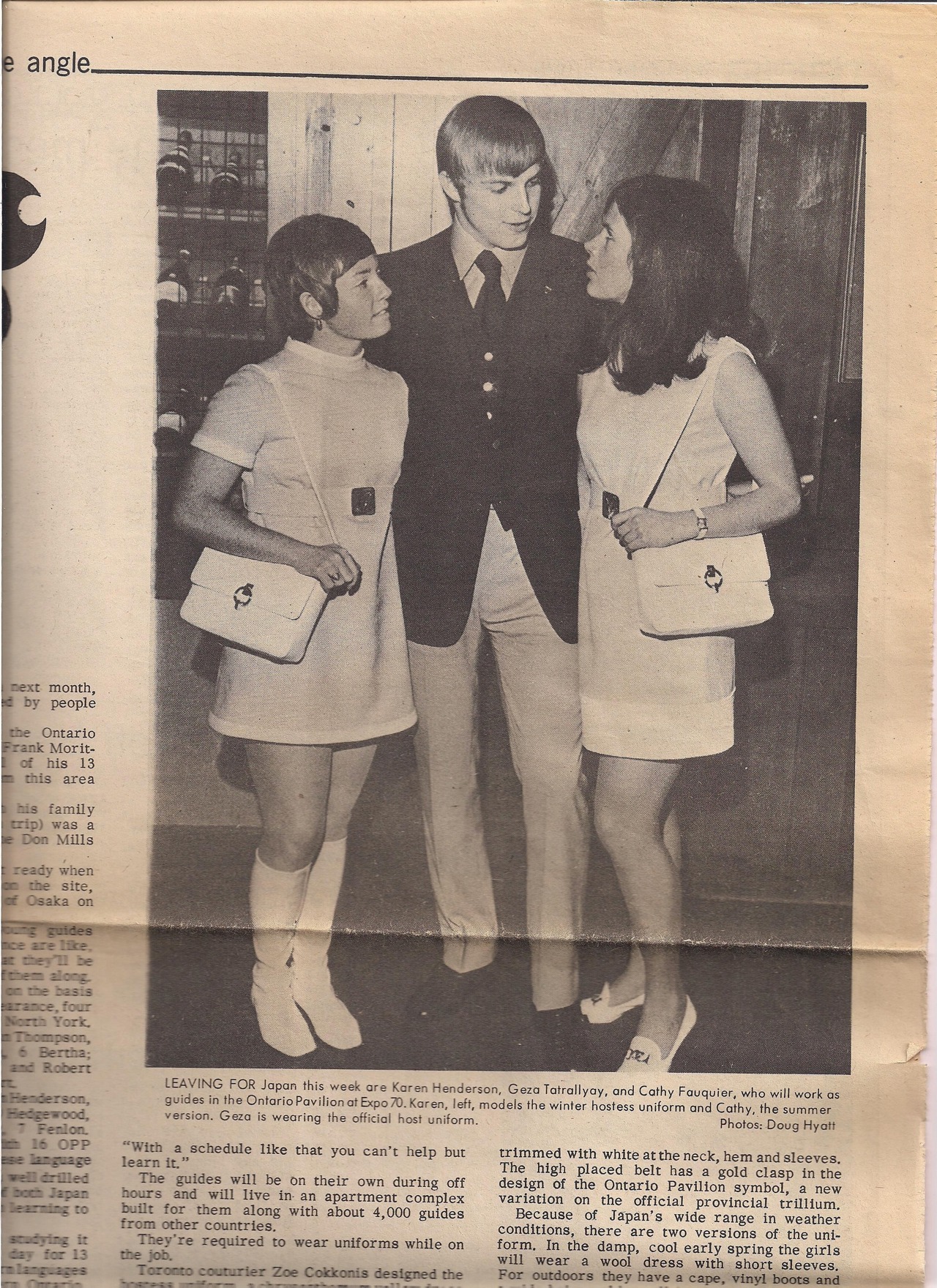

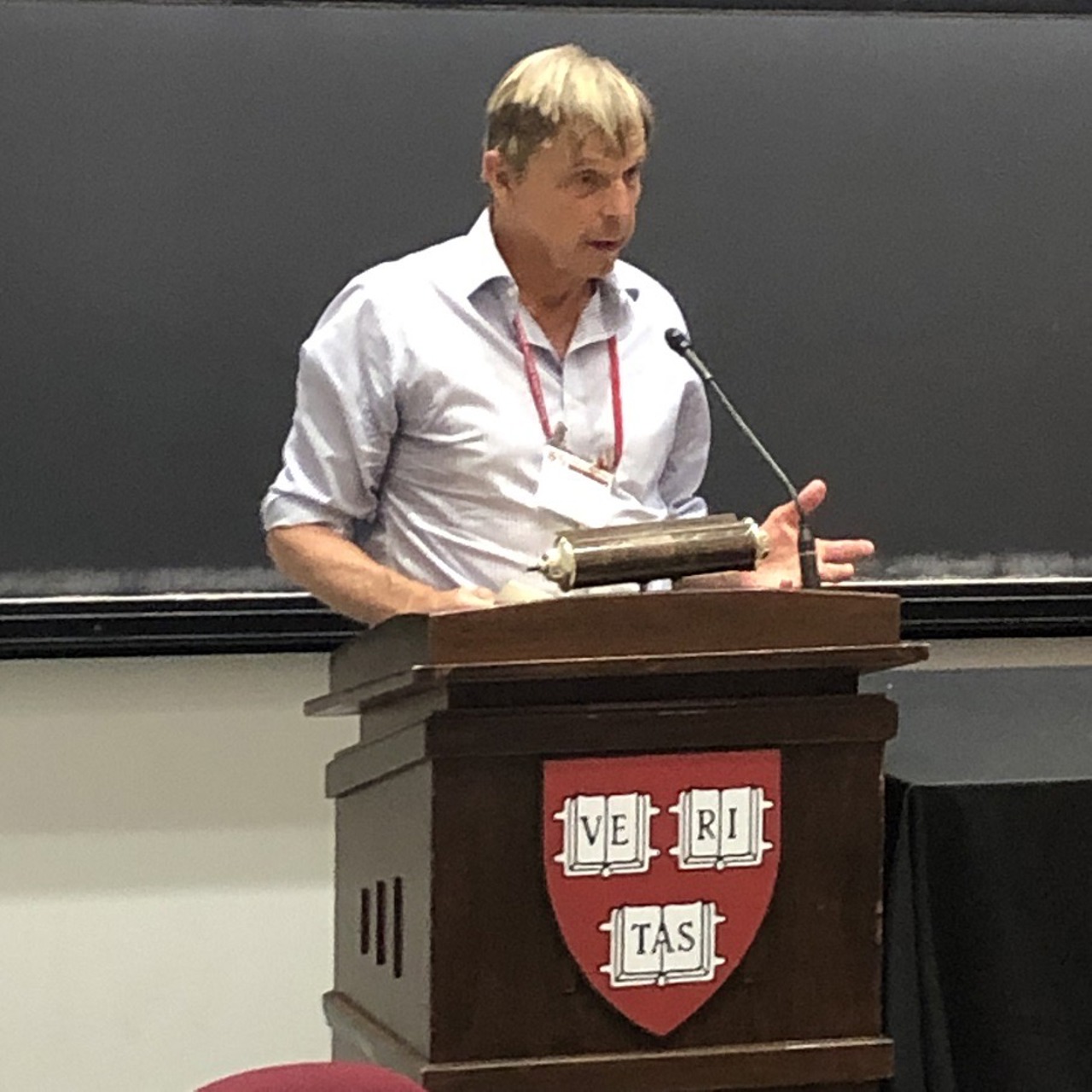

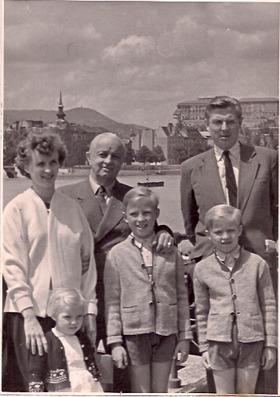

Born in communist Hungary in 1949, Geza Tatrallyay escaped with his family when he was nine years old, settling in Canada. He attended Harvard, going on to Oxford to read Human Sciences and then to the LSE to study economics. Tatrallyay was also a championship fencer, representing Canada at the 1976 Olympics. He pursued a career in international finance and was later instrumental in helping to establish a number of small firms, with a particular focus on renewable energy. The author of 17 books, Tatrallyay has a new novel currently in publication. This narrative is excerpted and edited from an interview with the Rhodes Trust on 14 February 2024.

Geza Tatrallyay

Ontario & St Catherine’s 1972

‘I remember it mostly like a movie’

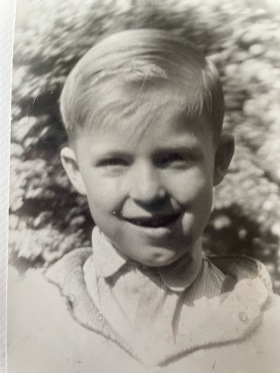

I started school when we were still living in Budapest. Whenever a communist dignitary visited, we would have to wave red flags, dressed in our Young Pioneer uniforms, and yell all kinds of communist slogans. Those were very tough years in Hungary. My father was taken in many times to the secret police’s headquarters and beaten up because he refused to spy on his father-in-law and on his boss. My uncle had managed to get out of Hungary and go to Canada, and he wrote glowing reports about life there, and that partly enthused my parents, Péter and Lily, to want to leave and go to a country where they could raise their children in dignity and freedom.

My parents made three attempts to escape. I remember the last, successful, attempt vividly. We were in the train, trying to reach a village where we had heard there was someone willing to help people cross the border. The train stopped, and a soldier opened the sliding door of the compartment and asked where we were going, and before my father could launch into the story he had concocted about why we were travelling so close to the border, my three-year-old sister piped up, ‘We’re going to Canada.’ The soldier was a bit stunned, but he handed the papers back to my father and said, ‘God be with you,’ and we made it out. I didn’t understand what was going on, just that something big was happening in my life. I remember it mostly like a movie.

Getting to Canada was a tough slog too, but we arrived there in Toronto on Christmas Eve, and it was a wonderful moment, because the Canadians were so very, very welcoming and helpful. My parents found jobs and I went to school and began to learn English quickly. We always spoke Hungarian at home and kept up a lot of the traditions, and my family still keeps those now too. We celebrate Christmas Eve and I bake Bejgli, the traditional Christmas poppy and walnut roll. And then, of course, we also do Christmas morning stockings, so we benefit from both traditions.

‘As to Harvard, that was a bit of a fluke’

I had my eyes on the University of British Columbia, but on the SAT form they said they would send the results for free to three universities, so I put down Harvard and Princeton, and Harvard was the first to come back and offer me a fairly handsome financial package and a scholarship.

I worked with Professor Roger Revelle at Harvard, putting together a major in human ecology, with courses from genetics, biology, psychology, anthropology, sociology, demography and environmental studies, and that was very much what Oxford’s Human Sciences degree offered, which I pursued later.

On applying for the Rhodes Scholarship

It was one of my roommates at Harvard, Don Gogel (New Jersey & Balliol 1971) who suggested I should apply for a Rhodes Scholarship. He was already in Oxford, and he wrote, saying, ‘You must apply for this....’

Studying in Oxford appealed to me especially because of the Human Sciences course there. It was a very stimulating course, and I still remember the professors, including Richard Dawkins, who was someone I admired a lot.

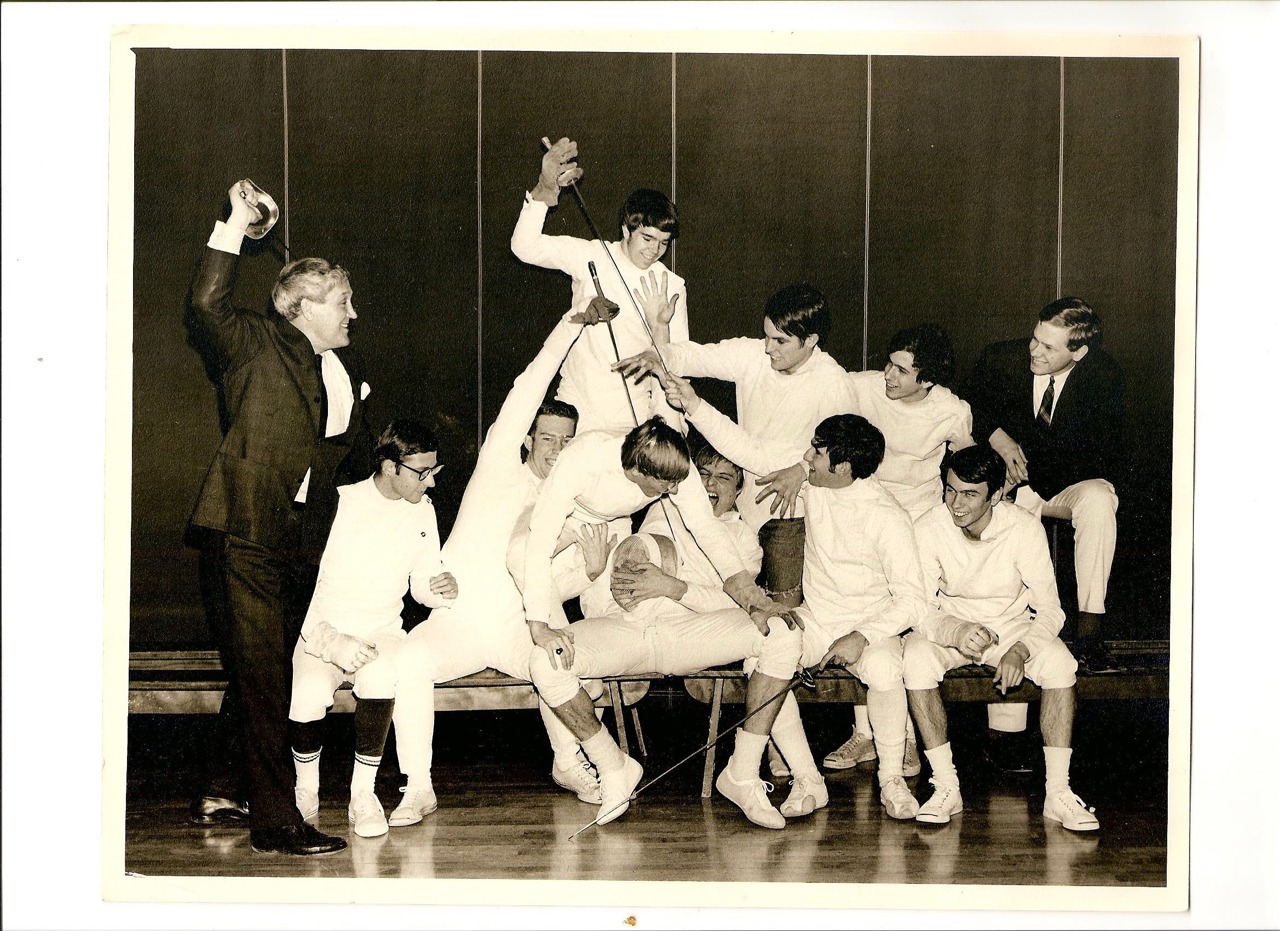

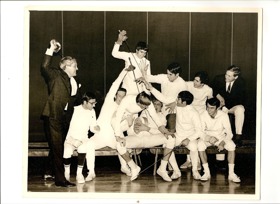

And, of course, fencing was a big deal for me too. Oxford had a Hungarian fencing coach, Bela Imregi, and I worked with him both in Oxford and in London. Oxford was a wonderful place, and I also used it as a base for travelling. By then, I was involved with the Canadian fencing team, and they were delighted that I was there because it didn’t cost them a lot to send me to all the competitions in Europe, so I would travel quite often.

I especially remember how kind the Warden, Edgar Williams, and his wife were to me when I got sick at the start of my second year: one or other of them came to the hospital every day to see me. And then, as I was preparing to leave, I went to see Edgar Williams to ask whether the Rhodes Trust might consider funding some further study for me, in economics at the LSE, because economics was the one human science I hadn’t had a chance to study at Oxford. At first, when I asked, he looked a bit stunned, but when I explained the rationale, he agreed, which was fabulous.

‘It made me what I am’

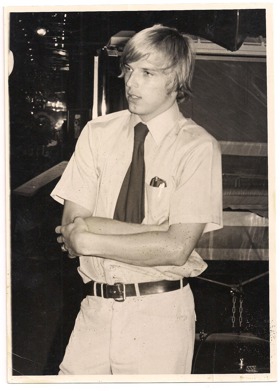

The Rhodes Scholarship shaped me. It made me what I am – the atmosphere in Oxford, life in England, the friends I made – and it also shaped my career, because it was my additional study in economics that meant I ended up working in international finance. I began working for the Canadian government, for the Department of Finance, and then they sent me down to Washington to work at the Inter-American Development Bank, which was extremely interesting.

The other thing that Oxford helped me with was my fencing career. The intense training I had in England with coach Imregi and the experience of all those European tournaments certainly contributed to my winning the Canadian national championships in 1976 and then going on to the Olympics.

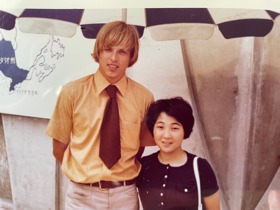

Living and working as a global citizen

After my time at the Inter-American Development Bank, I took up a post at the Royal Bank of Canada. That meant a lot of travel, which was wonderful. I had met my wife in Washington. We got married in 1980 and then, over the next ten years, we lived in London, Montreal and Frankfurt. It was after that that I decided I wanted to go back to Hungary to see if I could help develop a modern, capitalist, democratic society, so we moved there as a family and in fact, both my children graduated high school there. Those attempts to develop things in Hungary didn’t work out, unfortunately, and I found it especially difficult when I saw the high levels of corruption in the business world at that time. So, we moved to Vienna, and I was able to help start two firms, investing money and persuading some of my Canadian friends to do the same. Both of those firms are still going and one of them, a renewable energy firm, has just celebrated the milestone of over one billion dollars’ worth of renewable energy projects in central and eastern Europe. The environment is something that is very close to my heart, so I’m very happy with that!

Vienna is also where I started to write, and my focus is still on writing. I love it, and it’s my default activity. I’ve produced 17 published books now; six are volumes of poems, six thrillers, three memoirs, a short story collection, a children’s book. I’ve written memoirs based on my own experiences and those of my family, and thrillers set against the environmental and political backdrop of the Arctic. I’m currently in discussion about a possible script and movie based on another of my novels that was set in Bordeaux, where my wife and I lived for a time. I’m also working on a new novel, a murder mystery set in Vermont.

A plea to the next generation

When it comes to offering advice to current and future Rhodes Scholars, I’m sure I would benefit more from their words of wisdom then they would from mine! But if asked, I would say, ‘Be yourself, and keep pursuing your dreams, and eventually, things will work out.’

I would also make a plea to the next generation to be serious about doing something about climate change. In the older generation, the political will just isn’t there to act urgently enough, so it’s down to you.