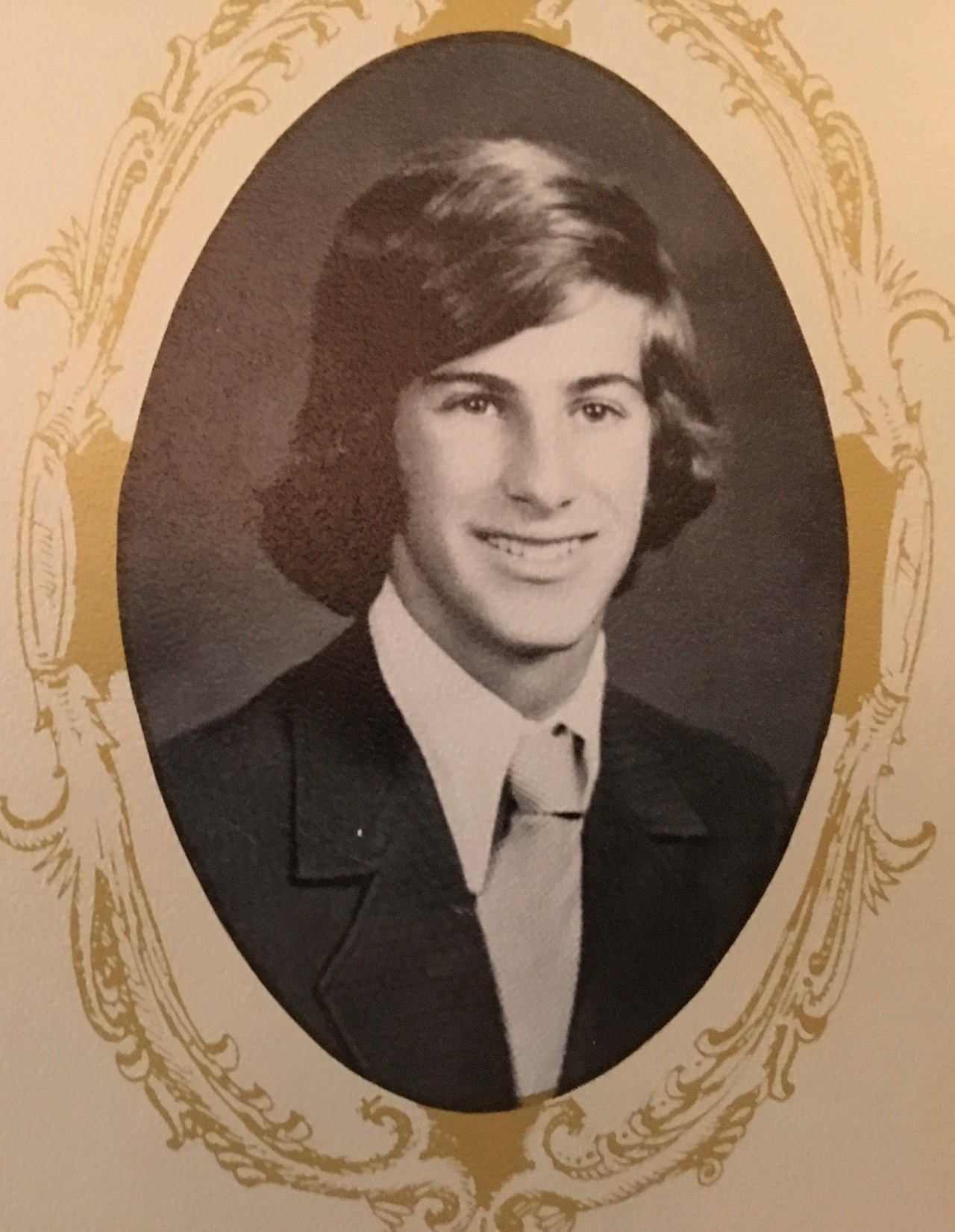

Born in Miami Beach, Florida in 1956, Fred Cohen studied at Yale before going on to Oxford to take a DPhil in molecular biophysics. Returning to the US, he took his MD at Stanford and held a fellowship and then faculty positions at UCSF, where he completed his postdoctoral training and postgraduate medical training. Alongside his work as a physician and research scientist, Cohen has also been a key player in venture capital firms supporting biotechnology. He was elected to the US National Academy of Medicine in 2004 and the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 2008. He and his wife, Carolyn Klebanoff, are among the founders of Sweetwater Spectrum, a non-profit organisation that creates and runs planned communities for adults with autism. This narrative is excerpted and edited from an interview with the Rhodes Trust on 6 May 2024.

Fred Cohen

Florida & Wolfson 1978

‘It was a fun-loving setup’

I grew up on Bay Harbor Island which was built on a swamp and was linked to mainland Miami by a causeway. As the youngest of four children, I frequently got brought along for any number of activities and I had to punch above my weight. We played a lot of sports – tennis, golf, football and baseball – we’d go sailing on Biscayne Bay. It was a fun-loving setup.

Things didn’t always break our way, though. When I was 12, my father passed away from post-surgical complications following a construction-related accident. At that time, my siblings were already in college, and given what had happened, my mother was not the easiest person to live with at that time. It was a difficult time, but it taught me that if something doesn’t go well, you can choose whether to say, ‘Woe is me!’ or you can go ahead and make your way against the tide.

On becoming a scientist

In high school, I was easily the best mathematician in South Florida— I literally had won that award — so it was a bit of an eye-opener to find that my college roommates at Yale were at least as good and probably better than I was. I also found it intriguing how serious people there were about their academic activities and how hard they worked and studied. That challenged and motivated me. By the end of my sophomore year, I had become a science person, studying biophysics and biochemistry.

In my organic chemistry class at Yale, I’d learned about something called the protein folding problem. It had really interested me and my professor, John Gerlt, advised me to talk to the chair of biophysics and biochemistry at Yale, Fred Richards. Fred gave me some papers to read and encouraged me to apply for a Bates fellowship so that I could work in Oxford for the summer between my junior and senior year. After that, I applied for another programme back at Yale which allowed me to spend my senior year continuing to work on the protein folding problem. The result of that work, ultimately, was accepted in the Journal of Molecular Biology, and that was my first publication as a scientist.

‘Something that’s truly life-changing'

I decided to apply for the Rhodes Scholarship not least so that I could have the chance to continue my scientific work in Oxford. I have a pretty good memory, which had helped me get through school and college, and it also helped me in the interview for the Scholarship. I remember flying through the first eight trivia questions later in my interview, but when they asked me the ninth and I didn’t know the answer, I just said, ‘Gee, you got me on that one,’ and they laughed. When I won, it felt unbelievable. You enter a process like this thinking, ‘Why not? Should be interesting,’ and you walk away with something that’s truly life-changing.

Oxford in the late 1970’s was a very different experience from living in the US. There were train strikes in the UK, and coal strikes, and the weather wasn’t particularly forgiving. The labs weren’t especially well furnished, and you had to think hard about the experiments you did, because you couldn’t afford to do very many of them. I worked six days a week, which was unusual in a British lab. It was the first time I realised that if you were smart and worked hard, you could really accomplish a lot. Had I not received the Rhodes Scholarship, I never would have believed that I could have a successful career as a scientist. But given the opportunity to try and with some combination of luck and skill, it worked out well.

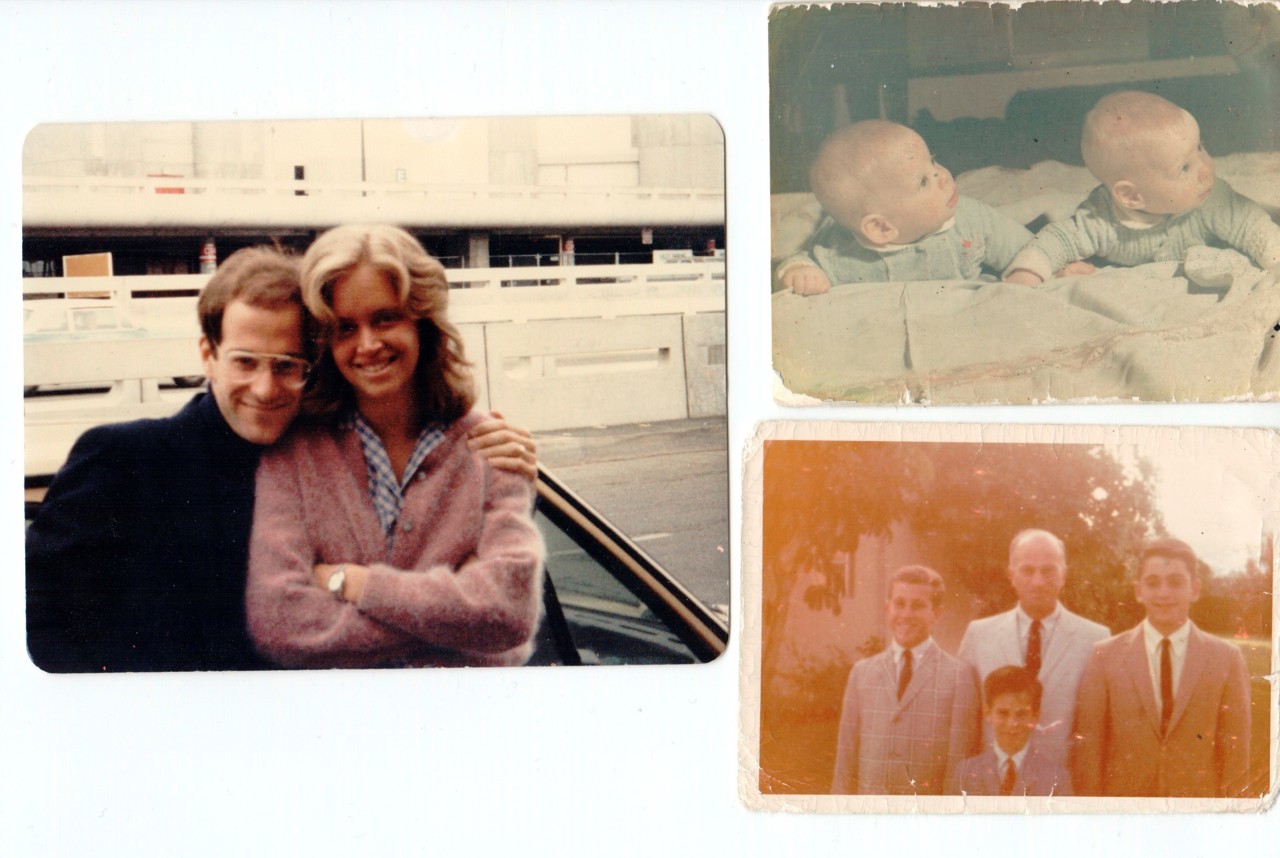

There was great camaraderie in my cohort of Rhodes Scholars. It was so good for me, being in a relatively august group of people all destined for a fair number of successes. Plus, they were just fun to be with. The time was remarkable for working hard in the lab, and Sunday mornings playing football On the St Catherine’s pitch. For vacations, I would fly back to the US to see my girlfriend Carolyn, who would later become my wife. She and I also managed to fit in some summer travel to Italy and up to the north of Scotland with friends.

‘I’d gotten used to working hard, and that just became my way of life'

Before winning the Rhodes, I’d applied to medical schools and Stanford let me defer, and so that is where I went after Oxford. I was also lucky enough to be granted a postdoctoral fellowship at UCSF while I was at medical school, so I spent four years combining medical school with research work as a postdoc. My post doc was sufficiently successful so that UCSF gave me an adjunct faculty position while I was a medical resident, and I was able to start setting up my lab. I’d gotten used to working hard, and that just became my way of life.

I started my academic medicine career as an endocrinology attending and while doing some consulting on the side, I became reasonably well known to one of the founders of Kleiner Perkins, a venture capital group. I helped them to look at various ideas they were going to invest in and soon, I started doing a great deal of consulting for biotech companies.

‘With ability, comes responsibility’

The most significant project that Carolyn and I worked on was the creation of Sweetwater Spectrum. In 1995, we learned that one of our daughters, Jane, was autistic. Part of the reason I did consultancy work was to make ends meet, because at that time, insurance didn’t cover the cost of care for autistic individuals. We had been looking around at places where autistic individuals in their 40s and 50s could live, and we didn’t see anything that looked like what we wanted for Jane. So, with another family, we embarked on a path that led to the creation of Sweetwater Spectrum, where Jane lives now. It’s an intentional community for autistic adults, and it’s become a real model for what people are doing in the US. Now, some groups in the UK are looking at it too, to see how it can be adapted for them.

I firmly believe that with ability, comes responsibility. I’ve been fortunate to benefit from a lot of abilities. Why wouldn’t you give back if you could? Working hard increases your chances of being lucky, for sure, and I’ve been enormously lucky. I’ve also taken the approach that I’m not going to let adversity allow me to fail or be restricted. Last time I checked, you only get one go round in life, so you might as well make the best of it.

Looking ahead

There’s a lot to be said for having a variety of careers in your life. Given the advances that have been made in medicine and wellness in the past few decades, it’s likely that many of the historical ideas about career trajectories and retirement should be set aside. We should think about our careers in waves of different topics that we wish to pursue. It’s helpful to link them in a way that allows you to progress from one opportunity to another, but we should not limit ourselves, or get stuck in careers that aren’t fulfilling. We should continue to see opportunities and take risks.

My goal now is to try and continue to change the practice of medicine. When I was a medical student and a house officer, I saw a real discordance between what you could do in clinical practice and what you should be able to do, based on the science that I came to understand, and that discordance still exists. In my role now as a capital allocator, I have the advantage that I can understand the scientific opportunities, the medical needs and the business rationale. I hope I can, in fact, continue to be helpful.