Born in Vienna, Austria in 1935, Erich Gruen came to the US with his family in 1939. He studied at Columbia University before going to Oxford to read for a second undergraduate degree in classics. After his PhD at Harvard, he took a teaching position at Harvard before moving to the University of California, Berkeley in 1966, where he eventually took up the post of Gladys Rehard Wood Professor of History and Classics. In 2008, Gruen became Wood Professor Emeritus at Berkeley. He is the author of numerous books and articles, including The Last Generation of the Roman Republic, The Hellenistic World and the Coming of Rome and Heritage and Hellenism: The Reinvention of Jewish Tradition. This narrative is excerpted and edited from an interview with the Rhodes Trust on 27 August 2024.

Erich Gruen

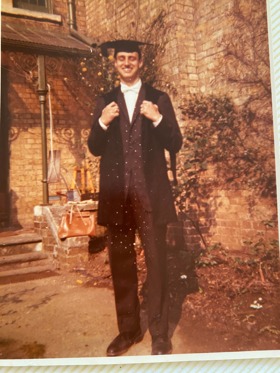

Virginia & Merton 1957

‘What they did was absolutely extraordinary’

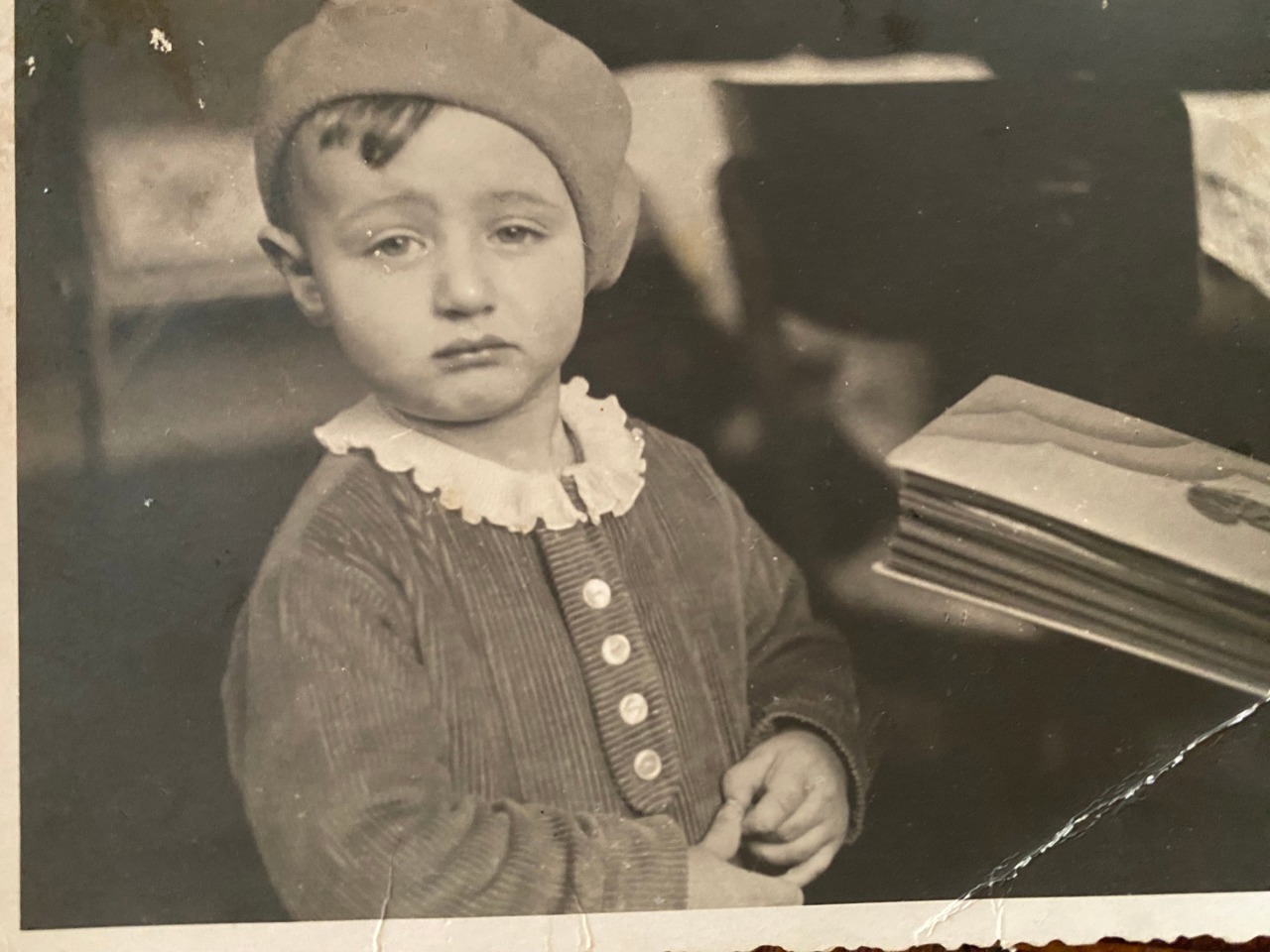

My family left Austria and came to the United States when I was four years old. Following the German occupation of Austria in March 1938 and then Kristallnacht in November 1938, it became clear that we needed to get out. In fact, my father was put into Dachau for a time – at that point a detainment camp and not an extermination camp. We did have relatives in the United States, and that was very important, because my mother’s aunt in Washington, DC was able to provide an affidavit that she would take care of us if needed. That meant that we could get my father released from Dachau, and we sailed from Hamburg in September of 1939, in the nick of time.

I remember nothing at all about arriving in Washington, DC. My parents wanted to start afresh, and they seldom talked about their earlier lives. Looking back on it now, what they did was extraordinary. In Austria, my father had been an accountant, but he had very little English and he didn’t have US credentials in his profession, so he took a job washing dishes. My mother was a seamstress, so that also brought in some cash. They always made sure there was food on the table and that my sister and I had clothes to wear to school. Eventually, they were even able to save enough money to buy a house in DC and a dry cleaning business.

We lived in Anacostia, which was a lower middle-class neighbourhood and perfectly respectable although, like all my schools as well, it was segregated. At my high school, almost nobody went to college, but we had some good teachers, and I especially remember my Latin teacher, Mrs Cantrell, who was stereotypically tough. Because of her, we all made sure we learned our Latin. I loved my schoolwork so much that I decided I wanted to train to be a teacher. I was also a great baseball fan, so when I wasn’t studying, I would go and watch the Washington Senators play. They almost never won, but I stuck it out. There was a saying that went around: ‘Washington is first in war, first in peace, and last in the American League.’

On applying for the Rhodes Scholarship

I chose Columbia because I had heard it had a very good teachers’ college, and also because it had a great football team which I was following then. At that time, Columbia had a system where you didn’t have to major in anything. I had no idea what subjects I was going to be interested in, so for me, this was a garden of delights. I loved my classes so much that I then decided I wanted to be a professor. It was as simple as that. I had the great benefit of meeting a particular teacher – Martin Ostwald – who made a huge difference in my life. He was himself a refugee from Europe who had left about the same time as my family. I went to him one day and told him I wanted to be a college teacher, but I didn’t know which field to go into. He said, ‘Well, you took my Greek history course last semester. You did pretty well. Why not become an ancient historian?’ And the rest, as they say, is history. We kept in touch for the rest of his life, and I owe him a lot.

At Columbia, I worked extremely hard, because I saw when I arrived that there were lots of students from top schools, and I thought I was miles behind them. I just ate up the courses on great books, including Contemporary Civilisation, which began in antiquity. The hard work paid off, and I became valedictorian, although at Columbia, being valedictorian wasn’t only about grade point average. I had also taken up rowing while I was there, and I was the director of classical music at the campus radio station.

I don’t know how I even first heard about the Rhodes Scholarship, but it had a ring to it that made it desirable. I went to the faculty adviser on overseas scholarships and said I was thinking about applying, but he discouraged me, because no one from Columbia had got a Rhodes for years. Then I went to Martin Ostwald who said, ‘You would have a good shot at it. You need to apply.’ I applied from Virginia, where my parents were living by that point. They announced the winners at the end of the last day of interviews, when all the finalists were still there. I thought they were going to give the names in alphabetical order, so when the first name they said began with a ‘T,’ my heart sank. But then, they did read my name out!

“Thank your lucky stars”

I wanted to do classics, but most of the British students had been studying Latin and Greek since the age of eight, so at first, there wasn’t a college that was willing to accept me. Luckily for me, the Warden of Merton was an avid rowing fan. I still have the letter from the Warden of Rhodes House telling me that I had finally got a college place. It began, ‘Thank your lucky stars you rowed crew at Columbia…’ And I did go on to row for Merton the whole time I was in Oxford. I even got into the second boat for the university too, which was a highlight.

In my academic work, I felt light years behind my colleagues, so I spent a great deal of time working on my languages. The tutorial system was wonderful, although I was bold enough to suggest to my tutor that instead of me reading out my essay each time, I could submit it ahead of time so that he could read it before the tutorial and we would have longer for discussion. He was generous enough to say, ‘You know, I think that’s not a bad idea.’ Alongside my work, I also did a lot of travelling in Europe, and I made friends who became lifelong friends. I enjoyed those years tremendously.

‘That legacy is permanent’

I went to Harvard to do my PhD, and while I have no fault to find with Harvard on the academic side, I was never fully comfortable and happy there. At that time, it was a very hierarchical place, and that was pushed in your face. I took a teaching position there once I’d finished my doctorate but when I got an offer from Berkeley. I immediately accepted it. When I went to tell the chair of the faculty, he thought at first that I was joking, and then he decided that this was a ploy on my part to get a promotion. I felt that was a sign of Harvard’s parochialism, and I knew that going to Berkeley was the right thing for me. The atmosphere there was so much more exciting and dynamic, and I’ve never regretted my decision.

I was interested in expanding the study of the ancient world beyond Greece and Rome, and one of the things I’m most proud of in my years at Berkeley was that I was part of the creation of a new interdepartmental programme, Ancient History & Mediterranean Archaeology. It spanned the worlds of Greece, Rome, Egypt, Syria, into Iran, and so on. It became a landmark, and a model for comparable programmes in other universities. I’ve been fortunate to have an outstanding group of students who have gotten PhDs from that programme. Of the 100 or so students who have received their PhD for whom I either directed the dissertation or was on the dissertation committee, I have kept in touch with around 80 or so. I now have three and a half shelves of about 135 books, all published by former students. When a former student of mine writes a book, the first thing he or she does is write to me and say, ‘I want this on your shelf.’ For me, that legacy is permanent, and it is the prime reward of my profession.

‘Have as much fun at Oxford as I had’

For me, the Rhodes Scholarship brought a combination of rigorous and demanding challenges on the academic side along with warmth and genuine friendships. I would encourage other Rhodes Scholars to have as much fun at Oxford as I had, and to make some good friends who may be lifelong. Enjoy their presence and be part of their future.