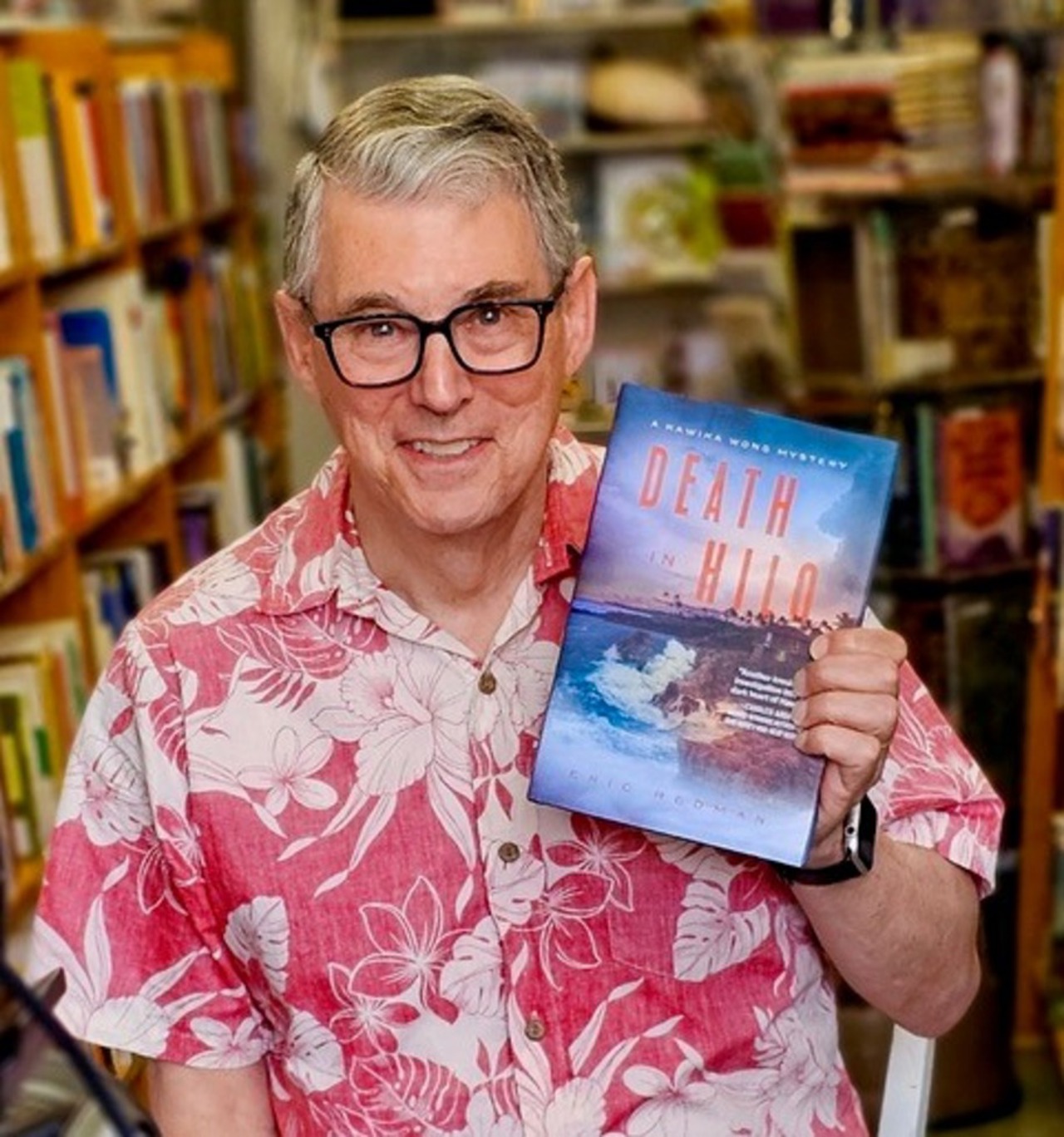

Eric Redman grew up in Seattle and studied at Harvard before going to Oxford to read for a second undergraduate degree in Philosophy, Politics and Economics (PPE). His first book, The Dance of Legislation, drew on his experience as a legislative assistant in the US Senate and was published during his first year at Harvard Law School. Redman went on to work in public policy and energy law and now focuses on creating sustainable climate solutions. In addition, he has written two works of detective fiction, Bones of Hilo and Death in Hilo. Active in philanthropy, Redman has established scholarships at Phillips Academy, Andover, Harvard Law School, and donates his book royalties to a scholarship fund at the University of Hawaii, Hilo. This narrative is excerpted and edited by the Rhodes Trust following an interview on 16 May 2024.

Eric Redman

Washington & Magdalen 1970

A Pacific Northwest childhood

My parents moved to Seattle from California when I was nine months old and although I’ve spent a lot of time in other places, Seattle has always been home base for me, and still is. My father’s family were all from Maine and descended from the people that settled there in 1630. My mother’s family were Ashkenazi Jews, non-observant and assimilated, who had settled in Boston and then New York City. My maternal grandfather was a colourful guy. In fact, he was Houdini’s accountant, so I’ve ended up with some trinkets Houdini gave to my mother. My parents met in Washington where they were both working on the New Deal. It was an unusual wedding, because I don’t think there was a lot of family approval on either side, but they had a very romantic courtship and marriage.

My parents were always financially insecure, and that weighed on them, but we were a close-knit family. There were three of us children, and I was the baby of the family. At that time, Seattle was a city of just 350,000 people, surrounded by woods and farms. We had a log cabin on Hood Canal, an arm of Puget Sound, with fabulous views of the Olympic Mountains and waters filled with fish. It was a magical place. We spent a lot of time outdoors fishing, hunting, and foraging for wild mushrooms.

In junior high school, I told one of my teachers she was stupid in front of the whole class because she couldn’t find Iceland on a map. I was a little shit. She dragged me by the ear to the principal but instead of telling me off, the principal agreed with me about the teacher and then said, ‘Have you ever considered going to Andover or Exeter?’ My parents didn’t have the money and were huge advocates of public school, but the principal said ‘Leave it to me.’ She helped me apply, and I got a scholarship. Andover revolutionized my life. The quality of instruction there was amazing. It opened my eyes to learning in a way I had never experienced.

A Harvard journey through the woods and to the Senate

After graduating from Andover and also after my first year at Harvard, I went home to Seattle and for my summer job I worked in the woods as a logger, the quintessential Northwest job. I was already aware that it was vanishing, and I wanted the experience. Logging was one of the most dangerous jobs, because this was virgin timber, trees up to ten feet in diameter. I got to go up to the spar tree with my spurs and my climbing rope, and I loaded trucks with these huge logs swinging around. I put chokers around logs. I absolutely loved it. I was thinking of not going back to school, just becoming a logger.

Although I got a prestigious scholarship to Harvard, it had no money attached, which is why I worked to pay for my college education. Luckily, I had high enough AP scores that I was allowed to go in with sophomore standing, so I went through in three years instead of four. That cost me a lot in educational terms, but I gained a lot in other ways, because I was able to take a year out, and that’s when I went to work for Senator Warren G. Magnuson (D-WA) and started to get deeply involved in legislation and Democratic politics, becoming the youngest legislative assistant in the United States Senate.

On applying for the Rhodes Scholarship

It was Zeph Stewart, the master of Harvard’s Lowell House, who said, ‘Have you ever thought of applying for a Rhodes Scholarship?’ I never had thought of applying; I didn’t know anybody who was a Rhodes Scholar. I’d been planning to go back to Washington D.C., and so I called my mentor there and asked for his advice. He said, ‘Well, you know you’re going to go into public service, so now, it’s a question of the quality of mind that you bring to that,’ and that’s why I applied.

The month before I was due to leave for Oxford, Senator Kennedy, Ted Kennedy offered me the job of being the staff director for the Senate health sub-committee in the coming Congress, which was going to try to enact national health insurance. To turn all that down and go back into academia, that was a gut-wrenching decision to make.

‘The quintessential Oxford undergraduate experience’

Working in the Senate, I had thought I was pretty important, but nothing takes that out of you faster than going to an Oxford college in the post-War years, with no bathroom on your floor and just a little electric fire in your room to keep you warm! I absolutely loved Oxford, though, and I had the quintessential Oxford undergraduate experience. You wrote your essay for your tutor every week and you would go along and read it, and he would puff on his pipe and tell you what was wrong with it and what to read for the next essay. The other thing I did at Magdalen was get involved in college rowing. I was in the first boat, and we were really successful for a couple of years. The classmates I rowed with became some of my very best friends in life.

There was nothing about Oxford I didn’t find wonderful, except the food and the fact that my room was really cold! At the end of my first year, I got married and my wife and I lived in housing for married students and got to travel, because the Scholarship came with a generous stipend. We spent five weeks driving around South Africa and neighbouring countries, and that sparked an interest in South Africa that has stayed with me the rest of my life.

After Oxford, I went to Harvard Law School. I briefly worked again in Senator Magnuson’s campaign in 1974, when he was re-elected to a sixth term, but apart from that, I never got close to the Senate again. However, while at law school and 23 years old, Simon & Schuster published my The Dance of Legislation. It was an unexpected bestseller, paid for my law school, and it’s still in print, more than 50 years later.

‘It was an incredibly exciting legal practice, but I loved it too much...’

I didn’t go into national public service, despite my experiences to that point. The primary reason was, we had to get back to Seattle. My wife had to get started in a law firm and I made the decision to support her and turn down positions within the Carter administration. We both took up posts in law firms. This was when I started to work in energy law, first in the Pacific Northwest, then Alaska, and then in Russia during the first phase of the post-Soviet period. It was an incredibly exciting legal practice, but I loved it too much, and in the course of all that work, I managed to lose my first marriage, which was devastating. I was very lucky, four years after that, to meet my second wife, who is wonderful. We’ve been married for 28 years.

One of the things that’s been especially important to me has been the pro bono legal work, especially around environmental and values-based projects. Here in Seattle, for instance, we are trying to save the Pacific salmon. Progress has been incredibly slow, despite the Endangered Species Act, but our fight goes on. Now, I’m also helping to create decarbonized energy solutions, and I think about climate crisis constantly. We won’t solve the problem in my lifetime, but we might be able to reduce the magnitude of what our successors have to deal with.

Other than time with family and friends, writing puts me in the state of mind I enjoy most. The impetus to write my two detective novels actually came from a terrible thing, when my brother-in-law from my first marriage was murdered in Seattle. I wrote the first novel in one year, in a crush of grief and anger. The books are set in Hawaii. I was determined not to use Hawaiian culture and history just as window dressing, but to make the story turn on them. My wife has native Hawaiian cousins, we had a home there, and we visit Hawaii a lot. It’s a place I’ve come to love, and one of the scholarships I support is at the University of Hawaii, Hilo, for the study of the native Hawaiian language.

On becoming aware of the power of philanthropy

The Rhodes Scholarship was hugely impactful for me. I had loved growing up in Seattle, but Oxford, like Andover and Harvard, opened the world for me even further. I have to say, I could see the inequity of the thing too: women weren’t eligible to apply for the Scholarship at that time, and Oxford was not a very diverse place. But despite the inequity of where Rhodes’s money had come from, I could also see that each of us Scholars was supported by people who had gone before us.

That idea was what got me into the business of raising money for Andover, for Harvard, and later, for the Rhodes Scholarships and other causes. I became aware of the power of philanthropy. To see how the Rhodes Scholarship has changed now is exciting. It has much greater diversity in every way, and there’s so much enrichment going on for Scholars via Rhodes House. For me, these are all reasons to give back to the Trust, and you know, by the time we’ve all finished giving back to the Trust, it’s not Cecil Rhodes’s money anymore, it’s ours.

“The reward for a good deed is the good deed”

To today’s Rhodes Scholars, I would say two things. The first is that it’s astonishing how rapidly your life whips by. So, be careful with your time. Use it for yourself, your family, your country, your causes. Use it for the things that matter to you, and try to give back. The second is something I learned from my father-in-law from my first marriage, who was an incredible philanthropist. He never named a thing after himself, and he never took credit for the things he did. He once quoted Gorbachev, who I believe was quoting Ralph Waldo Emerson, to the effect that ‘the reward for a good deed is the good deed.’