Born in Minneapolis in 1964, Eric Olson studied at Macalester College before going to Oxford to begin a second undergraduate degree in History and Modern Languages and then pursue an MPhil in Russian and East European Studies. After a period working for the US-USSR Trade and Economic Council, he moved into management consulting, serving as a Partner at Mitchell Madison Group and then at Boston Consulting Group. A growing interest in the environment led Olson to shift full-time into working with multi-national companies to improve their environmental and social impacts, with a focus on energy and climate change. He served as Senior Vice President, Advisory Services at Business for Social Responsibility (BSR), and then as Managing Director, Sustainability Services at Accenture, and now works as an independent advisor to corporate management teams, investors and public agencies on scaling climate mitigation and adaptation solutions. This narrative is excerpted and edited from an interview with the Rhodes Trust on 29 August 2024.

Eric Olson

Minnesota & Merton 1986

‘I had to be very responsible’

I grew up in Saint Paul, Minnesota, and my family’s ancestors were all from Scandinavia. My dad’s side of the family were farmers and mom’s family were city people from the get-go. There are lots of fun stories in our family folklore, for example, that my great grandmother ran away from Sweden after her parents said she couldn’t consort with the stable hand she had fallen in love with. She found herself at the railway station in Minneapolis and another Swedish woman offered her a job as a chambermaid, and off she went.

I had two younger sisters, and we grew up in Summit Hill, which is a nice old historic neighbourhood. It sounds like such a mythical cliché to say it now, but it really was the sort of upbringing where all of us kids in the neighbourhood would just play outside all day during the summer and only come home for dinner. But then my parents split, and my dad left the family when I was 11. From that point on, I was the man of the house. Things were hard at home, and I had to get serious pretty young and start to contribute financially to the family.

What I have a very clear memory of, through those years, is the incredible string of mentors and benefactors who were so important to me. That probably started with the Boy Scouts, where I discovered camping. I also had wonderful teachers. I went to public elementary school and then got a scholarship to St. Paul Academy (SPA). What the scholarship didn’t meet, they gave me a job in school to cover, so I actually worked as a janitor, including during the vacations. Church was a big part of my life too, and I also loved sports. When I got to SPA, I encountered soccer, and that became my number one. I was very into science, and the other thing I encountered at SPA was Russian. The school had hired a German teacher who also offered Russian, and he got us hooked by doing a slideshow: onion domes, John le Carré, Cold war spy cloak-and-dagger stuff. I fell in love with it.

On applying for the Rhodes Scholarship

I had applied to a few of the Ivies and got offers, but they insisted on taking my father’s income into account even though he was not willing or able to contribute. Whereas Macalester, God bless them, took my story on its value and gave me a full ride on the same deal as SPA, with a work-study on campus. I had fabulous professors, and our advanced seminars only had four or five students per class. It was the first time I was living on my own without all the family responsibilities. Some students struggled with the transition, but for me, it was, like, ‘So, let me just get this straight: I get to go to class, someone is going to cook for me, and then the rest of it is all about me? Wow!’

I double-majored in pre-med and Russian. I was always interested in other countries, and that was an itch which developed and became part of my Rhodes story. My closest friends at Macalester came from Bangladesh, Bolivia, Slovenia, Malaysia and Japan, so the world sort of came to me. One of my other friends was Russian, and he and I did a radio show of Russian music together where we would play the Soviet national anthem at the start. This was at the height of the Reagan administrations ‘Evil Empire’ rhetoric, so people were a little puzzled. When I was a senior, I finally got to go to the Soviet Union, to what was then Leningrad. The city was like nineteenth-century Russian literature come to life, and it was a real political education too. It changed everything for me.

I had been going merrily along, applying for med schools, but then my chemistry professor, Truman Schwartz (South Dakota & Merton 1956) who had been a Rhodes Scholar, told me about the Scholarship. I had had no idea about it before that, but I thought it sounded cool. The whole application process was so interesting. I was impressed and intimidated by how wide-ranging and thoughtful and personal the questions were. And it was only when I saw how tense all the other candidates were that I realised how big a deal this was.

‘I was absolutely gobsmacked’

I chose Merton because Truman Schwartz had gone there, and it turned out to be perfect for me. I just immersed myself in it. I remember sitting in the old library there, reading about the Mongol invasions of Russia in the medieval period and realising that at that same time in history, there would have been someone sitting in the library exactly where I was sitting, studying whatever they were studying. I really loved the tutorial system too, and my tutor in history, Robert Gildea, was amazing.

I started a second undergraduate degree, but this was the mid 1980s, when I could see the changes happening in the Soviet Union after Gorbachev, and I decided to focus more on the Soviet Union. The Trust agreed to pay for an extra year so that I could study for an MPhil. I wanted to geek out in infinite depth, and working with the professors at the Russian Centre at St Antony’s College gave me that.

I had very mixed feelings about the class system in England at that time, but I loved the English friends I made, and I felt very at home. Plus, I was and still am a massive J.R.R. Tolkien fan. One day, I was in my rooms in Merton Street and the person who came to clean was chatting to me. She saw my collection of Tolkien books and said, ‘Well, of course, Mr Olson, you’ll know that these were Professor Tolkien’s rooms when he passed.’ I was absolutely gobsmacked.

‘A lightbulb went off for me’

After Oxford, I started working in US-Soviet trade development. At that time, I had zero interest in business. But as I saw the impact that business and businesspeople could have in the service of other things, I began to take it far more seriously. I came back to the US and joined a group who had left McKinsey to start their own management consulting firm. They were looking for what they called ‘Alternative candidates,’ and, being a contrarian person, that sounded pretty good to me.

That’s how I got into business, and I really caught the bug. I loved the problem-solving. After a while, though, I wanted more purpose to what I was doing. I had encountered a lot of writing about ecology and the economy and was connecting back to those early experiences I had had camping, which had sparked my love of the outdoors. Then, when I was a partner at Boston Consulting Group, I got the opportunity to do a piece of pro bono work with Conservation International, who were asking, ‘How should we work with business to achieve our conservation agenda?’ Boom! A lightbulb went off for me. That was 1999, and it was too early for big firms to take an interest in this sort of thing, so I jumped out and began to work independently. Then BSR came to me and said they wanted to build a consulting capability within their non-profit, to help companies work out what they needed to do to create sustainability. 16 years of building that team and that organisation, and I have never looked back.

‘Be mindful of your inputs’

It’s a privilege to work every day in the service of things you care about. Sometimes, though, it is tough to wade through the data on climate change and see the work that we’ve got to do. We must turn it into an inspiring vision, show people that this is a chance to make real change. And what I love about the work I do is that I must learn something brand new pretty much every week.

To today’s Rhodes Scholars, I would say, take seriously the need to make your own work sustainable by taking care of yourself. Be mindful of your inputs. It’s like the intellectual equivalent of eating right. There are so many opportunities to immerse yourself in negativity, and we just don’t need to go there. And when it comes to your time at Oxford, resist the temptation to over-specialise. The value of breadth, the ability to make connections, will serve you well. Things change so quickly, and you need to have the ability to reapply what you know.

Transcript

Interviewee: Eric Olson (Minnesota & Merton 1986 [hereafter ‘EO’]

Moderator: Rachel Wood [hereafter ‘RW’]

Date of interview: 29 August 2024

RW: Hello. My name is Rachel Wood. I’m a member of the Global Engagement Team of the Rhodes Trust. Today is 29 August 2024 and I am conducting a Zoom interview with Eric Olson (Minnesota & Merton 1986). During the 121st year of the Rhodes Scholarship, Eric is helping us to launch the first ever Rhodes Scholar oral history project. We’re very grateful to you, Eric, for this gift to the community and to the future Rhodes Scholar community.

EO: Happy to do it.

RW: Thank you. Let’s get started with just a few formalities. Do I have permission to record this interview?

EO: You do.

RW: And can you please state your full name?

EO: Eric Ross Olson.

RW: And finally, from where are you recording this interview today?

EO: I am at my home in lovely San Francisco, right in the middle of the city, not too far from Golden Gate Park.

RW: Thank you. Let’s get started from where it all began. So, Eric, where and when were you born?

EO: I was born in Eitel Hospital, North Minneapolis, Minnesota, 17 January 1964.

RW: Wonderful. And tell us, do you know where your ancestors came from?

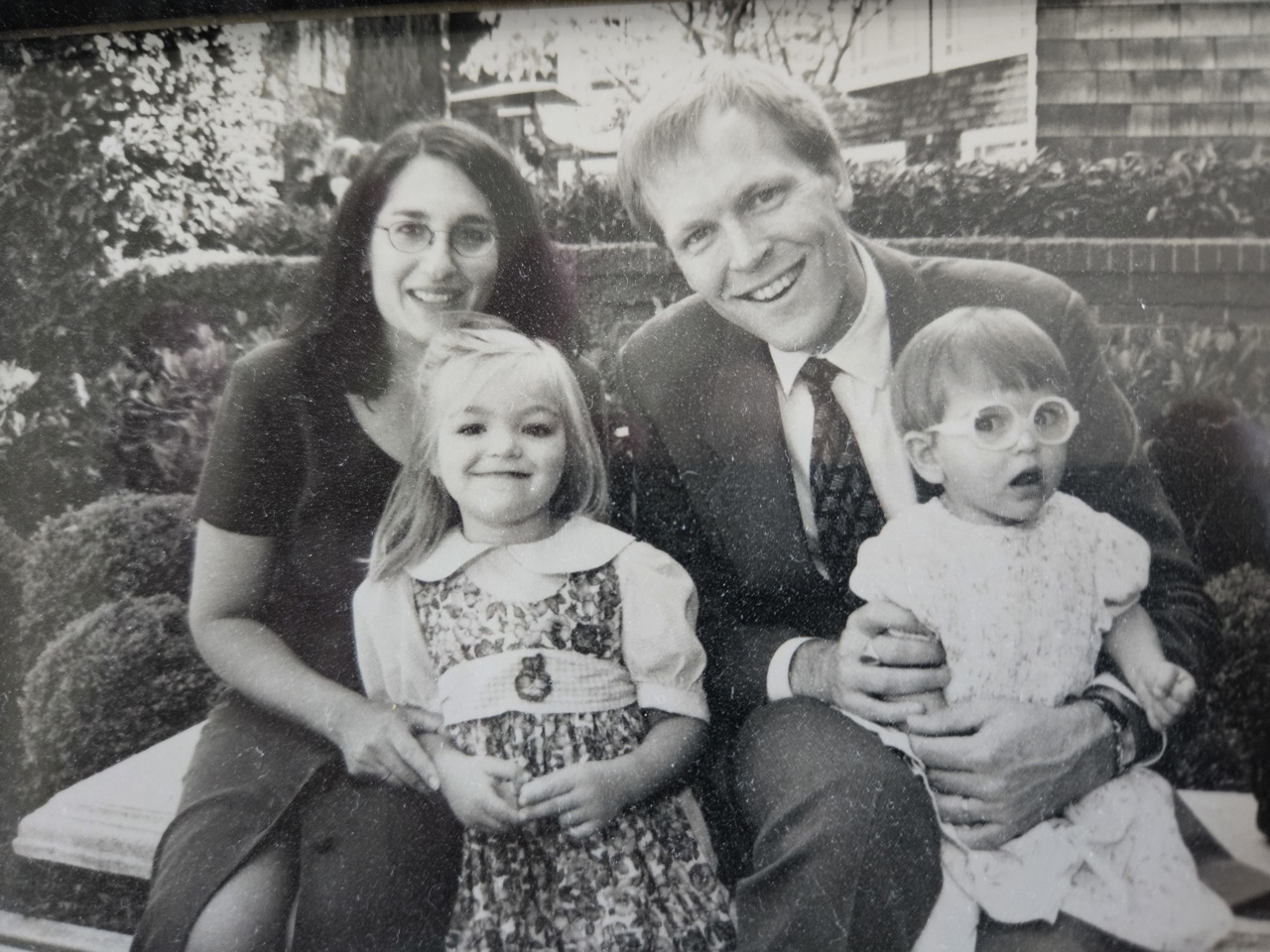

EO: Well, indeed I do, and my mother has helped me with memory. So, this [holds up photo board] she had made from old photos and gave me as a gift. I’m a mutt, Norwegian and Swedish, and yes, that matters to people from that part of the world. Dad’s side is all Swedish, as far as we know, and Mom is a mixture of Sweden and Norway: Dad’s side of the family comes from a small village about 250 miles southwest of Stockholm - called Kvistbro, and Mom’s side are a mix of Swedes (maternal grandparents the Andersons and the Halls) and Norwegian (her father a Gjertson from a whaling village on the coast). My grandparents on my dad’s side are Ole Olson and Marcella Otterson.

Scandinavians and all came as part of the waves of immigration in the early 20th century, it was a bad economy in Scandinavia. Lots of fun stories, particularly the great grandmother on my mother’s side. As the family folklore goes, she fell in love with a stable hand, was not allowed to consort with said stable hand, so she left and got on a boat all by herself and came over. She found herself at the railway station in Minneapolis, alone and not speaking any English. A Swedish woman – this is the way it went, with the waves of immigrants coming in – walks by and asks her if she’s Swedish and gives her a job in her hotel as a chambermaid, and off she goes. So, various fun things like that, that I’m sure are a mixture of fact and fiction.

RW: But it’s wonderful that these stories got passed down.

EO: Yes. My dad’s side of the family were farmers from Red Wing, Minnesota, and Dad came to the city, because he didn’t want to be a farmer. Mom’s family showed up at the railway station in Minneapolis, and were city people from the get-go. That’s all I know. The other thing about origin: for some reason, I am destined to be surrounded by women, and it goes way back. There is an incredible imbalance of women to men genetically in my family. My grandmother had seven sisters and no brothers. I grew up in Saint Paul, Minnesota with a mother and two sisters. My parents split and my dad left when I was 11, so for most of my upbringing, I was the man of the house. And then it turns out, I’m capable of producing only women as well. So, now I’ve got two daughters. The best I could do is, insist when it was time to get a dog that at least the dog be a male.

RW: Well, I believe these women have made you the amazing man you are. And so, tell us a little bit more about the family you grew up with in Saint Paul and your community. Do you remember what your community looked like?

EO: I absolutely remember the community. So, I grew up in what’s called the Summit Hill neighbourhood of Saint Paul, which is a nice old historic neighbourhood. Now it sounds like such a mythical cliché, but it really was the sort of upbringing where there were a lot of kids in the neighbourhood and we spent every day after school outside, running around with the other kids in the neighbourhood. You left in the morning in the summer and your parents wouldn’t have any idea where you are. The only rule is, when the streetlights flicker on, you’ve got to come home for dinner, and in between those times you’re out eating lunch at whoever’s house you happen to be at when it’s lunchtime or I was roaming around on bicycles by the Mississippi River.

So, it was very communal. Things were hard at home. As I mentioned, my parents split when I was 11. By then, I had a sister. She was nine at the time, and my mother was pregnant with the youngest. So, in some ways, I became Dad when I was 11, which had a big impact on what I did. I got my hooligan years out of the way at a pretty young age, I think. I have a police photo from when I was 12 years old; I had this nasty habit of breaking into construction sites and playing on the equipment. That said, I have a very clear memory through those years of an incredibly important string of mentors and benefactors, people outside of the house who were super important to me. That probably started with Boy Scouts. I discovered camping at 11,12,13, somewhere around there, and the older boys in the group played a big part in pushing me along to grow up, get a little bit tougher. Teachers, such wonderful teachers: I went to public elementary school in Saint Paul, then got a scholarship to go to a wonderful independent private school in Saint Paul called St. Paul Academy. There, I had a series of amazing mentors/counsellors who I will be eternally grateful for. We had no money, but I got an almost full scholarship to St. Paul Academy, and for what the scholarship didn’t cover, they gave me a job at the school. I worked as a janitor and maintenance person at the school. So, whenever we had school vacations, the short ones during the year and certainly all summer, I stayed and worked at the school and had a very different kind of mentor then: you know, the funny, crusty old janitors. Wonderful, wonderful people.

The other part of the community that was important [10:00] was church. There was a United Church – sort of, mainstream Protestant, and that’s where the Boy Scout troop was located, so those two things were connected. I had church, community, Scouts, and sports. You know, very typical. The only difference being that I got serious younger than most, because I had to work. I needed to financially contribute to the family. It was the only way we could make it work.

My mom went back to school. She hadn’t been in the workforce since before she was married, so it was a classic start over for her, and we had to pull together. As a result, I was very, very, close to my sisters.

RW: Can you share your sisters’ names?

EO: Karen is two years younger than me, and Amy is 11 years younger than me.

RW: Wonderful. You mentioned sports; what sports were you interested in?

EO: Yes. So, when I was little, it was baseball. T-ball, I guess they call it, before you can actually swing at a pitch, and then baseball. I played exactly one half of one season of what I now call American football, just football: broke my arm about the third week in and my mother said, ‘That’s the end of your football career.’ I was small for my age until I was halfway through high school. So, that was really it, and it was just baseball, until I got to St. Paul Academy, and one of the many great things that happened for me there was, I encountered soccer. We were one of the first schools to have a soccer programme and, not surprisingly, it was because our math teacher was a soccer player from Spain. He started the soccer programme. And so, starting when I was 13, I played soccer every season all the way through. Fast forwarding the story, I played it at Oxford when I finally got there.

It was by far my favourite sport. And then I added basketball when I grew. I grew eight inches in one year when I was in junior high school. I had to wear knee braces as a result. Your body is not supposed to do this. But anyway, when the bones hardened back up and I was 6 feet 1, 6 feet 2, 6 feet 3, I got into basketball. But it was never the thing that soccer was for me.

RW: Soccer is a great sport. I can’t wait to hear more about soccer in Oxford. And tell us, at St. Paul Academy, did you start to develop some specific academic interests?

EO: Yes. So, a couple of things, which ended up turning into majors in college. I loved school from the beginning. I mean I really, really ate it up. When I was in junior high school, one of the disciplines they had at SPA that was so fantastic was writing, and I had the kind of teachers who said, you know, ‘The more drafts the better,’ and they would edit all of them.

So, by the time I was in eighth grade, I was writing multiple versions of papers and really loved that, which has served me very well since. But probably passion number one, the thing that I just got super interested in, was science, chemistry in particular, but not only. For reasons of complete accident – and this had a huge impact later – they taught Russian at SPA, at a time where that was a very strange thing to find - in 1976, 1977. I started taking Russian, and that was only because the person that SPA had hired to teach German also knew Russian, so they hired a German teacher and he gave them Russian as well. Man, was that cool.

And I remember that decision very clearly, because people still ask me – because it became a part of my professional life – ‘Russian? What, do you have Russian family?’ Like, why would you take this language? And it was very, very simple, prosaic. The guy was a genius marketer. He came in and he did a slideshow for class, onion domes, John le Carré, Cold War spy cloak-and-dagger stuff.

RW: Sold.

EO: And then, the different alphabet. I remember that was a thing. I said, ‘Oh, my God, that is so cool.’ And I think it was between Russian, German or Spanish. Couldn’t think of a reason to take German or Spanish and the Russian stuff looked cool, so I just started, and then fell in love with it.

RW: Wow. As early as seventh grade.

EO: So, by the time I made it through high school, I was pre-med, a lot of science, but I kept the Russian along and ended up, when I then went to college, double majoring. The language had become important enough to me that I kept it going, even though I had no idea what I was going to do with it, honestly.

Except I knew from the beginning I wanted to go there. I think that was probably the main thing.

RW: Did you make that happen?

EO: I did. I had a great, great couple of Russian teachers and one – Sally Lincoln was her name – was quite young and really planted the seed when I was a junior in high school. She said, ‘You’ve got to go study there.’ So, the combination of the literature, which I loved, and the travel bug planted that seed. Finally, in college, I ended up studying abroad over there, while it was still the Soviet Union, which was effectively, my first big out-of-country experience. Talk about culture shock. As I mentioned, we didn’t have any money growing up, so with the exception of a few camping trips to the Rocky Mountains, my whole life, until I was 21 years old, had been spent in a triangle, one mile on each side: Mom’s house, SPA, and then I ended up going to Macalester College. I was a local boy and then suddenly, I was in the Soviet Union in 1985/86, which was extraordinary.

RW: At that time, did you have any dreams or aspirations for the future?

I think of Fareed Zakaria’s wonderful book, In Defense of a Liberal Education. I was the poster boy for this. I mean, I loved science. I loved literature, especially Russian literature. I loved Shakespeare. SPA offered a wonderful teacher, who gave a year-long Shakespeare course. We read all the major plays, and I loved that. Math. I ate it all up in high school. So, dreams for the future at that time? It’s hard for me to remember that, honestly. I wanted it all. Daydreams of being a great scientist was probably the closest I had to any plans. But I really bought the idea that it was too early to make those kinds of decisions, and that I was just going to go to college and do a lot more of everything.

RW: Right. Well, SPA sounds like a special place to offer that smorgasbord and for you to be able to taste the menu. [20:00]

EO: Yes. And art. I still have some of my work on the wall from high school. We had a wonderful visual arts teacher - Hazel Belvo, so painting was another thing. I was on the school newspaper. I loved journalism. So, I was working and studying all the time, and that was helpful in terms of the tee-up for the Scholarship at some point.

This is where I developed a habit which maybe wasn’t 100% healthy, but between working and studying through high school, I’d go to bed at one or two in the morning and get up at six, and that became my thing. By the time I got to college – I remember this very distinctly – and my life became really my own, I moved into a dorm and wasn’t the family guy, I thought I was on holiday. So, while a lot of other kids were coming into college going, ‘Oh, my God, this is such hard work,’ I’m like, ‘Oh, wow! So, let me just get this straight: I just get to go to class, someone is going to cook for me at the food service, and then the rest of it, it’s all about me, baby? I like this.’ I think I continued with the same regimen because, you know, it was just normal. I did sports, I had a campus job, and I worked a lot. I knew people who did well at the last minute, cramming. That was not me. I always put the time in.

RW: Yes. And it sounds like that was an aspect you enjoyed, right? You were, sort of, wired that way.

EO: Yes. No one was telling me I had to do it. I actually think that’s so important too, and it’s really had an influence on how I think about things with kids. If anything, I was in the odd position where my mother would fight with me now and then because she felt like I was spending too much time on school, and that I was working too much. She wanted me to do more things around the house. So, that was an interesting one, that I was studying too much and spending too much time on sports. I had to fight for it. So, now in college, it was all for me. I didn’t have parents telling me I had to do all this stuff.

RW: Yes, yes. Very self-driven. Tell us more about applying to college at Macalester. Did you apply to other schools?

EO: I did, and it was one of those things. Obviously, I loved the idea-, so, I applied to a wide range of schools, including a few of the Ivies. Harvard and Princeton were the two I chose, and then I can’t remember-, I must have done a few of the other small liberal arts, like Carleton in Minnesota, and Middlebury, I remember, was on the list, because of Russian. World-famous language programmes, and I thought, ‘Why not?’ And it had a great reputation. And I got into every school I applied to, but the Ivy League schools insisted on taking my father’s income into account for financial aid, even though he was not willing or able to contribute.

So, basically, I couldn’t afford to go. I got into Harvard and Princeton. Whereas Macalester, God bless them, basically took my story on its face value and said, ‘Okay,’ and I got a full ride at Macalester: sort of same deal, with some residual that I had to pay, but I got work-study on campus to do that, the same deal on which I went to SPA. People hear that story and go, ‘Oh, that’s too bad.’ I really don’t have any regrets about it, and that says a lot about Macalester. When I went, it was not the prominent school it became. What I got out of Macalester was a continuation of SPA. Fabulous professors. I did do one thing at the insistence of my high school counsellors, who knew how entangled I was with family and things. They said, ‘Look, if you’re going to stay in town and go to school-’ and one wonderful counsellor at SPA – I remember her name: Mrs Donovan – she looked straight at me, she said, ‘You’ve got to promise me you are going to live in the dorm.’

You know, ‘You’ve got to get out. Your family will live without you. You’ve got to move on and focus on yourself.’ It was great advice. Anyway, I moved onto campus at Macalester and never regretted it. I ended up marrying a woman who had been to Harvard, and when we compare our undergraduate experiences, I’d take mine ten to one.

And she would say the same, you know? Interesting, small, liberal arts, teaching-oriented colleges are very different. I had open-door relationships with all my professors. Class size of 20, with advanced seminars being more like four or five students per class. Just a fundamentally different learning directly by spending hours with people who were at the top of their field in chemistry, etc. So, it turned out to be a good thing.

RW: Yes. That’s beautiful.

EO: And here’s the other important part about Macalester, an itch that I developed at SPA which continued and then became part of the Rhodes story: I was always intensely interested in other countries. And so, the thing I was worried about in going to Macalester was, like, ‘Damn, I’m going to be staying in Minnesota. I want to get out and see other places.’ Well, it turned out, Macalester did and still does recruit about 20% of its student body from overseas. So, internationalism is a big part of the curriculum. Kofi Annan, the former UN Secretary General is an alum of Macalester and there’s a centre for global citizenship. Though I was in Minnesota, a significant portion of my social circle were people from – if I just list my closest friends – Bangladesh, Bolivia, Slovenia, Malaysia, Japan. So, the world came to me.

RW: Yes. That’s really cool.

EO: Which was super, super important to me and had a huge impact on what I ultimately would choose to do later on.

RW: Well, expand a little more on what defined your life at Macalester. How were you spending your time academically and otherwise?

EO: Let me think about that. So, I worked very hard. That continued. But I did finally learn how to lighten up a bit. In fact, this is very classically me. So, I was very straight. Well, I skipped over something important, because this becomes important in the Rhodes interview process and other things. I was not raised a very religious person, but one of the things I did in high school, a very important part of my social life [30:00] was that I ended up, through a friend, attending a Baptist church, as much, initially, as a social thing, when I was 13 years old. It became a very big deal, I was very engaged. I did an adult baptism, very serious. And again, not only was I not pushed to do this by parents, but my parents also thought I’d gone a little cuckoo. So, here was this kid going to church, kind of a Jesus-head, studying and working and playing sports all the time and there’s a kind of parent who would go, ‘Oh, my God, dream come true.’ But mine were like, ‘Hey, you study too much, and what’s all this God stuff?’ So, it was, kind of, funny.

RW: Well, that helps set the scene as to what defined your life in Macalester and beyond.

EO: Okay, right. So, I was very straight, very serious, and then, I think I had my first drink, ever, as a sophomore in college. So there’s a little bit of contrarian-, so, when did I decide it was a good idea to have my first drink? The night before my first orientation or business meeting as an RA for my dormitory, in which my job was going to be to enforce responsible behaviour. And so, of course, I show up to this first meeting completely looped, for the first time in my life, and made a silly scene of myself. So, I learned to let loose a little bit, but still worked very hard. Another touchstone at Macalester was the group of students I saw most often were fellow chemistry majors. Chemistry not only was my major, but I was a lab assistant, so I was in the department even when I wasn’t in class.

So, that became a focus. Russian and the language lab became another focus. Soccer team was my big sports thing. Continuing a theme from my past, the other job that I had to do for money is washing pots and pans in the campus food service. A really great experience, in a sense. I mean, obviously there is a lot about it that wasn’t great. But there was a guy I washed dishes with who was a Vietnam War veteran. A working-class, out-of-luck tough guy. I think he had addiction problems. I’m not sure. But we would work together every night, and talk. We would go to professional hockey games together.

So in college, I just put together this combination of things. There were campus social activities. But again, I worked hard. I mean, Saturdays and Sundays, I would go out and have fun, but otherwise, I was doing a lot of reading, working. My horizons in the arts were expanding. Music: that was actually a big thing. I’m a lifelong, very, very passionate music fan, and in college, music was for me, what it is for, I think, a lot of people, but where my horizons just exploded. I did my own radio show. One of my other international friends in college was Russian, and this is a little more contrarianism, and this is Reagan, ‘Evil Empire’ days, right? So, this is Reagan, term one, ‘The Evil Empire,’ ‘Mr Gorbachev, take down that wall.’ Here we are in Saint Paul, Minnesota, so Leonard and I decided we were going to do a Soviet music programme on the campus radio station. It was Russian, not Soviet as in patriotic Soviet, but Russian music, mainly classical, but some folk, and we thought it would be fun, especially just given the political climate at the time, to open our show every week by singing the Soviet national anthem and then see what kind of phone calls we would get if anyone was listening. It was fascinating, right? And in those days, Minnesota was a little gentler, political discourse was a bit gentler than it is today. We would get calls now and then from people, just really confused: ‘Why are you guys singing the Soviet national anthem? You otherwise seem like normal kids. What’s your problem?’

RW: Right. That was the exact response you wanted, wasn’t it?

EO: It was pretty much what we were trying to do, yes. So, the international student organisation had parties and events, and it was just a very full, very rich experience. I loved it. Loved it.

RW: Tell us about your voyage to Russia, then, as a part of your study abroad.

EO: Oh, yes. So, this was when I’m, in retrospect, proud of the persistence and grateful for the advice which I got, which was to be persistent. Russian was always my hardest subject. Science and other things came to me a lot easier. But I stuck with it, and I stuck with it for a very simple reason: I wanted to go. I tried two times, I applied to the study abroad but Soviet Union at a very politically restricted time, so I think the number of spots available per year were in the tens, not hundreds. There was one programme in Moscow and one in Leningrad. I applied two years: ‘No,’ No.’

Only when I was a senior did I finally get accepted to the CIEE – Council on International Educational Exchange – programme in Leningrad. And so, I finally got that. It meant I was away for graduation but there was just never any question in my mind that I had to do this. But that was extraordinary. So, when I was a sophomore at Macalester was literally the first time I got out of the US and that was part of the world opening to me as I went. I did the classic summer, got the Eurail card, backpack, and took off by myself and went to Europe, and oh, my God! You know, literally, I had not done anything like it. An extraordinary experience. Loved it. So, anyway, that bug was very strong.

Now it’s December 1985 and I arrive in what was then Leningrad – now St Petersburg. [40:00] Did we fly into Helsinki, or did we fly somewhere and take the train to Helsinki? Anyway, I know we took the train from Helsinki into Leningrad. I remember arriving in Leningrad, it’s December 1985, and it is dark 22 hours a day. I’m from Minnesota, so I think compared to the kids who were coming there from SoCal or wherever, the shock was probably somewhat less. And it was everything that I hoped it would be. It was a near-out-of-body experience. It was behind the Iron Curtain, it was dark, and I had a certain amount of pride. I had done winter camping. That’s actually a thread that I didn’t mention earlier from my Boy Scout days. My camping continued to progress through the years, YMCA and other programmes.

So, I fancied myself a pretty hardcore, hardy, outdoors person, including winter camping up on the Canadian border and some pretty cold stuff. And nevertheless, Leningrad in the winter, I finally understood, those black fur hats are not a fashion statement. Any wool knit thingy that we would wear? Not good enough. Because somehow, the Gulf of Finland and the Baltic Sea, it can be below zero and humid. Go figure, right? The wind is whipping off the water and you just get this bone-penetrating, unbelievable cold with stiff wind that only animal hide will keep it out.

Now, a high-end Gortexy thing would do it, but in 1985, we didn’t have that. So, I had to buy all local gear. I got there, I bought a thick wool army coat and rabbit-fur hat.

It was just an extraordinary experience. It changed absolutely everything. It’s really hard to recreate the environment. Cross-cultural, as any place would be. I had been studying the language for more than ten years, but that was my first immersive speaking experience, which is different. But, I was able to get around. But just then, the whole political thing: I had to worry about whether I was getting people in trouble by befriending them. I was definitely followed. Every now and then there would be a KGB provocation: someone would pretend to be a persecuted dissident, come up to me asking if I could bring papers to the embassy for them,.... you just knew. No real dissident is going to come in an unnaturally loud voice on a crowded street and ask me to take documents to the American Embassy, in horrible English. But the fact that you had to think about these things, it was really profound. And I loved it. I was there from December through the end of the school year. I found Leningrad – now St Petersburg – was Russian 19th-century literature come to life. It is still, probably, my favourite city in the world.

RW: Have you been back?

EO: I have, though now, it’s been a long time. I’ve been back since the Wall came down. So, this was under the old regime, No market prices. I lived in an old building well, everything there is old, in the centre. It’s Italianate and was built in the 1700s. My dorm room was on the Neva River. I looked out of my dorm room windows at the Winter Palace, across the river.

RW: Unreal.

EO: All the toilets were broken and there were mosquitoes in the basement. I mean, the conditions were horrible, but it was this beautiful, beautiful place. When I went back in the 1990s, sure enough, the thing had become a super high-end condo, and it was like a millionaire’s residence, or something. When they finally privatised everything, it was insane.

So, it was lot of political education. Those were the years of great antagonism between our countries. I remember when we bombed the embassy in Libya in the 1980s and there were anti-American protests at the university, on our way into class. Posters up the wall: ‘Shame on the American aggressors.’ It was an education, in all true senses of the word. And friendship, that was the thing I took away, this incredible Russian duality between official life and home life, or street life versus home life. I found friendships intense, super generous, warm. People protected what the state couldn’t control, and so, your life, sitting around with a bottle of vodka or wine around the kitchen table, in a communal apartment, you’d have these amazing, six-hour conversations.

So, my love for it deepened, and ultimately then – and this starts to get to the Rhodes part of the story – here is one of many times where fate intervenes in the best-laid plans. So, here is Mr pre-med man. I go off to Russia, but I had applied and had an MD/PhD spot waiting at Washington University. But 1986 just happens to be the time when a guy named Mikhail Gorbachev becomes General Secretary of the Soviet Union. So, suddenly, with this polite secondary interest in Russian literature, I go there…and the economy starts opening, the place becomes wildly interesting, and that changes everything for me. So, that took root when I was over there.

RW: Now, had you applied for the Rhodes Scholarship yet?

EO: So, I had. I had. So, all in this stew of time. So, backing up to the application process – because this, frames my experience there – I didn’t know what the Rhodes Scholarship was. I think I had a vague association – it sounded important – but I had no idea what it was. I was the first person in my family on either side to go to university. This was not the sort of thing we would have had any awareness of. No one in my family knew what it was. My mentor, chemistry professor at Macalester, was a guy named Truman Schwartz (South Dakota & Merton 1956). He was a Scholar from the 1950s or 1960s.

Anyway, I’m merrily going along, I’ve taken the MCAT, I’ve done my med school applications, and he goes, ‘You know, you should apply for the Rhodes Scholarship,’ and I go, ‘Well, what do you get?’ And again, no association with this. ‘Oh, well, they pay your way to go to Oxford.’ Oxford sounded cool. I pictured this ancient place. [50:00] So, he said, ‘Why don’t you apply? You don’t have to give up on med school but just defer.’ So, I went through the process, and when I got it, the combination of my excitement with Russia and the English system for medicine being different...Kids go straight from high school into med school. So, for that and a bunch of reasons, medical school credits from England would only transfer 50% back.

So, basically, Truman and others said, ‘You know what? You’ve got these multiple interests and your other major. Why don’t you just defer med school and indulge these other interests while you’re at Oxford? Do something that Oxford is more known for: history.’ So, that’s how that decision was made and then, of course, the changes in the Soviet Union deepened and there I’m off and running, bye-bye med school, at that point. Again, that was not a plan. That just happened.

RW: Yes. Yes. It’s fascinating. Do you have any memories related to the interview itself for the Rhodes Scholarship?

EO: Oh, God, yes. It was a fascinating process. Very challenging. The bits that I remember: I mean, obviously, I remember the big panel interviews. I do think that first in writing the essay and then much more in the panels, I was intimidated/impressed/intrigued by how wide-ranging and thoughtful and personal the questions and the focus was.

So, first of all, anything that you said that you were interested in, there was going to be a world-class expert in this panel asking you the hardest ethical, unsettled questions in that field, which I don’t think I knew until I got there, but woe be to you if you had claimed knowledge or interest in something you couldn’t back up: you were not going to make it through that process.15 experts in their respective fields, hitting you with questions at the same time around a big table. So, I remember very specifically the hard, ethical questions that they zeroed in on, and so, for me, there are two I remember. I think a military guy asked me this, so the stakes were high. I think I was registered as a conscientious objector - on religious grounds. He zeroed in ‘How do you reconcile your faith with science?’ basically. So, he asked me the science versus faith thing - how do you reconcile that? Others on the panel included theologians and scientists. People I knew weren't going to be satisfied with a superficial answer.

I’m just, like, ‘Oh, my God. How much time do we have. Really?’ And I gave whatever answer I gave. I just had a belief – that the only thing I could do was be really honest. Because the other interviewer was a doctor, and he zeroed in, same thing: super hard, ethical question, ‘What do you feel about the right to die?’ or unplugging someone from life support. So, the ethics of assisted suicide, or something to that effect, or, is it ever okay to pull out the plug as a family member? All I remember about my answer was trying some version of, ‘Well, there’s an argument on this side, argument on that side.’ I think the thing I said that I was conscious of being most impressive to the committee was saying, ‘I don’t know. I can’t reconcile those things, and I really hope to learn more about it, because I think it doesn’t add up. I haven’t found any guidance on this.’ So, that’s what I remember, and I remember coming away from those two big panels – one was the state, one was the regional thinking, ‘I have no idea how that just went. I had bumped into the other kids going through the process, and I’m going, ‘Really?’ They were so impressive. I guess lucky for me therefore, and maybe this is part of what allowed me to behave the way I did, I think it was an advantage not having any family or expectations around this. It was just a scholarship programme. Worst case, I’m going to go to a fantastic med school programme, so how bad it could be? I like to win things, so I’m not saying I wasn’t up for it, but I guess my naivete was a bit of a strength.

RW: I would agree. Do you remember them calling your name, and the first person you told?

EO: Yes, I do. I remember the other people from my region who were selected, as well: it was Heidi Tinsman (Iowa & Balliol 1986), Virgil Wiebe (Kansas & Jesus 1986) and myself, and there might have been a fourth. I remember us standing around and talking. I remember a guy who didn’t get it, and I liked him a lot, and he was a Marine, wearing his stuff, and I think they had gotten him on the killing, religion versus warfare question. He was regretting having given too confident a buttoned-up answer. Anyway, this was a social setting unlike anything I had ever seen.

There was a bit of an aura of unreality, to me, and I remember when I found out I had gotten it and saw the reactions of other people, it was only then that it occurred to me that this was a pretty big deal. I mean, I was happy right away, but then, when I told other people....for example, I was doing an internship at the University of Minnesota as a lab assistant for a physiologist, Irwin Fox. I told him, and he fell off of his chair. He said, ‘Do you understand what you’ve just done?’ I’m like, ‘Er, I guess.’

RW: Yes. Thanks for sharing that. It’s fun to take that journey back with you. But let’s now jump into your time in Oxford and arriving in 1986 and deciding to read Russian and East European studies at Merton.

EO: So, that’s not actually what I started to read.

RW: Oh, really? Do tell us.

EO: So, it was all about advice, because I didn’t know what I was doing. But the advice I had gotten was that given the breadth of my interests and what [1:00:00] people tended to have a good time doing at Oxford, they said, ‘Do a second BA.’ And I got into Merton. Merton was, again a Truman Schwartz influence: he had gone to Merton in the 1950s or 1960s. What a wonderful thing that ended up being. I had no idea, because I didn’t know the colleges, but it is either the oldest or one of the oldest. I think they argue about that.

RW: They do.

EO: Like, one has the oldest charter, the other had the oldest building. But it’s really old, and very English, which was perfect, because my whole attitude going into this, I just loved international, I loved being immersed. I arrived at Merton to do a second BA in modern history and languages. So, I had history tutors and Russian tutors.

The Russian tutor at Merton was also the chaplain at Merton. He was a religious man, Dr Everitt. And then there were a couple of different historians. So, I read a year of modern history and languages, and this whole format was just a mind blower for me: the one-on-one tutorial. I loved it. So, I did a year of that, and I really liked it. Go read a pile of books and then write an essay, one per week, and then read it out loud to your professor. And up to you to figure out, because the list of books you get is ridiculous. You’re not going to read all these carefully. You’re going to choose, both speed, depth, and choice, etc. But, there is probably no other programme where I would have-, in Russian, for example, had a whole semester-long course which was just, ‘Read Anna Karenina in the original Russian,’ the whole term, which was extraordinary.

It was unlike anything else I had done with the language, to really, really soak it in like that. But the one story from that first year at Merton that I can’t resist telling-, it was funny. So, I ended up with a history tutor who I liked a lot: Robert Gildea. He was young, he was smart and he had a little bit of a bee in his bonnet about Americans. He was just looking to get me, in a way that didn’t bother me. I found it fun. And we developed a rapport. When he hadn’t sufficiently intimidated me, I remember he just burst out one time, ‘You bloody Americans. You’re so full of yourselves,’ or ‘Not respectful/intimidated enough’ or-, I can’t remember what his thing was, but that was, sort of, symptomatic. Oh, I know how I provoked it.

So, I don’t know what this says about me, but anyway…the tutorial process in history meant that every week you’d get this unbelievable question posed. So, for example, one was, ‘To what degree could the transfer of power in post-colonial Africa be described as a painful one?’ Painful transition, colonial to post-colonial, so, 1940s to 1960s Africa. And he had a list of 12 books, and he goes ‘Look across the different systems: the Belgian Congo, the former English colonies and the former French colonies.’ Three different systems. So, it was a couple of different books on each one. Read them and then do just this one essay on describing the transfer, the decolonisation of Africa and the degree to which it was painful. Oh, my God. And this will be wrong, but the idea will be right: so, for that one, I came up with a scheme: ‘I’m going to compare and contrast the French, the English and the Belgian systems. I’m going to abstract the most salient cross-cutting issues, etc.’ Anyway, so, I read my essay to him. He goes, ‘Well, Mr Olson, you’ve done an admirable job highlighting-You’ve painted some broad themes, largely correctly... but I think you’ve really failed to account for the specific and unique experiences of Kenya this and Uganda that, etc....’. So, basically, you’ve gone too general and synthetic and you haven’t really gotten into the meat. You’re kind of superficial.’ So, I go, ‘Okay. Tick. I get it now.’

So, he goes, ‘Okay, for next week: “Describe the role of the military in Latin American politics”.’ I go, ‘Okay.’ So, again, 12, 14 books, one on Peru, Bolivia, Brazil, etc. And I’m thinking to myself, ‘Okay, so last time, my thing was, I got too broad, this and that. I tried to do too much and therefore was superficial. So, here, I’m going to go narrow and deep, and just really nail it on one or two. Yes. I’m just going to dig deep, deeper and deeper.’ So, I read that, and he goes, ‘Well, Mr Olson, you’ve done an admirable job. You know, your take on Brazil and Nicaragua, etc. But you’ve really failed to capture the important cross-cutting themes in the-,’ and I’m just, like, ‘Oh, you’re really having fun with me now, aren’t you? I don’t think I said that, but that’s how I felt.

So, then, the next essay question he poses, which is getting closer to the wheelhouse of things I knew coming in, is something like ‘Looking across global – Soviet and other – experiences, to what degree was there really a distinctive Chinese road to socialism?’ And so, then, again, a list of books on China, Russia, etc. I can’t remember, intellectually, what approach I took, but it was probably a mixture of the two, a balance. I don’t know what I did. But he goes, ‘You know, I hate to say this, but I think you’ve really got it,’ and says this wonderful thing and I’m just sitting there, looking at him, and I’m just getting this big smile on my face while he talks. He finally finishes and says, 'Why are you giving me this idiot grin?’ And so, I turned my paper around. It was blank. I had extemporised the whole thing.

RW: You’re kidding!

EO: So, then, that is what provoked, ‘Oh, you bloody Americans.’ You know, basically, ‘Why aren’t you afraid of me?’ is what he was saying: ‘You just do what you want.’ But, you know, it was maybe a week or two later, and I got a personal invitation from him to go out drinking with him and his wife.

RW: There you go.

EO: [1:10:00] I was, like, ‘Oh, my God.’

RW: That is an incredible story.

EO: So, that was year one, and then it became clear to me: I loved the programme, but it was very general and, you know, with the Soviet Union continuing to open - right? It was just getting more and more-, I was, like, ‘Wow.’ I started talking to people and realised that I could flip over to- first of all, I had no desire to only do two years at Oxford, so I said, ‘Okay, how could I focus more on the Soviet Union, and how could I stay here longer?’

RW: Yes.

EO: And it turned out, the Trust would pay for a third year if you had a good reason, so, I flipped over, and instead of doing a second BA, I said, ‘I’m going to do an MPhil in Russian and east European studies.’ And even luckier for me, all the hardcore faculty for that programme are at St Antony’s College, but it was no problem for me to remain resident at Merton and do all my tutoring at St Antony’s.

The process and the experience I had with the tutors at St Antony’s, in the field where I just seriously wanted to geek out in infinite depth - it was heaven. I had a wonderful, wonderful thesis supervisor, a guy named Harold Shukman, who I adore, and a great, great thinker. Archie Brown, Michael Kayser, and then the lecture series they had were these wonderful gatherings at St Antony’s where the conversation was always dominated by these émigré east Europeans, showboating for one another and criticising one another’s points of view. I just loved the way English criticism was so different: ‘Well, thank you very much for the very interesting things you’ve said about A, B and C, but don’t you think that your ideas are basically fundamentally flawed and you’re an idiot?’ I mean, the language seemed very polite, but if you were listening to what they were saying, they were basically just-,

RW: Tearing you apart. Yes.

EO: ‘He’s a moron.’ It was so funny. And the east Europeans, a very different culture. Very comfortable generalising about the national character of Germans versus Czechs versus Russians. I just loved it, absolutely loved it. Met my best friend there at St Antony’s during my second year. We were close, very close, spent a lot of time. He is an Arabist. Well, I guess he’s a lot of things now, but-, not a Rhodie. And so, that’s another interesting thing about the Rhodes years for me. I’m not sure this was brilliant, and maybe then gets into advice.

I probably, in retrospect, wish I had spent more time with the Rhodes cohort, although the programming has changed. I think it’s easier now. Rhodes is doing a better job connecting Scholars and having events at Rhodes House. We didn’t have as much of that. But even what we had, I didn’t invest much in. I was carrying the mindset I had as a foreign exchange student in the Soviet Union to England. I said, ‘I didn’t come here to hang out with other Americans.’ So, I ended up at Merton College, the most English of colleges. I think there were five or six Americans at the whole college, and I just went native. I didn’t really want to hang out with the other people on the programme, not because I didn’t like them. It’s just, I didn’t think that’s why I was there. So, interesting. I didn’t come away with that kind of Rhodes network, really.

But, you know, I certainly feel like I profited from it immensely. In the advice column, I’d probably come back and say, ‘Oh, a little bit of balance there.’ And if they had the sort of things they had now at Rhodes House and those networks and the theme-based lectures and other things, I would do that.

RW: Yes. It’s just vastly different in the past decade than it has ever been, and I would say that the attraction now is that it’s more of a global Scholarship.

EO: Right.

RW: So, when you do go to Rhodes House, it’s not just Americans. You are more likely to have cross-cultural interactions.

EO: I think I also had very mixed feelings about the pomp and circumstance. I still felt like the welfare kid from the Midwest, and there was a little bit of the white-gloved servants at formal Rhodes things. I was just a little uncomfortable. Easy for me to say now, ‘Oh, I’ll just get over it and go for the ride,’ but it was a little uncomfortable for me at the time.

RW: Yes. Yes. Tell us more about your impressions of Oxford and the UK in the mid-1980s.

EO: So, one of the things I was acutely aware of, and it was good for me, but I certainly was very sensitive to it: the class consciousness among the British students was unlike anything I had experienced. At the same time, as foreigners, we had a pass. So, we as foreigners – as Americans, at least. I don’t know about other kinds of foreigners – if you wanted to tune into cliques and cool kids, which I pretty much did not, but I certainly was aware of these dynamics, Americans were never going to be in the inner circle of cool, but nor were we going to be looked down upon. From my accent or any of my other personal information, they couldn’t place me, the way they could another British kid.

And so, what I was acutely aware of and found funny, is at Merton, people could peg one another, not just from north versus south, which even I could do, with my ear, but they could tell east Durham from west Durham. These crazy, local things. And I could really tell, you know, the northern, working-class, less posh kids were very much placed accordingly in the social order of things. My upbringing would have put me in the category of a dock worker at outer Liverpool, the English equivalent of what I grew up. So, I found it interesting. I ended up gravitating more towards the northerners, I guess, but not really, even. It just didn’t matter. I was blissfully rootless, right?

So, that was one thing. The other thing, you know, this was Thatcher, a more articulate Reagan and a more articulate Reaganism. I remember the universities facing, for the first time, the need to fundraise, and how interesting that was. My area of study gave me a window. It was particularly interesting to do what we called Sovietology outside of the United States and gave me a real perspective on how politically tinged a field it was. So, to give you an example, I think there was one major American scholar – Steve Cohen, out of Princeton – one, who was on to this idea that there were alternative currents of thought and undercurrents in the Soviet Union that could break loose and become what we saw. England, outside of the US, that was the centre of gravity.

They didn’t believe in the completely monolithic totalitarian model [1:20:00], that all Russians are the same, and if you look back, Sovietology in the United States was significantly funded by the CIA. It was a political field. It was not as much, or not in the same way, in England, so, that whole perspective that I got, especially in my field but not only in my field, being an American outside of the United States in the 1980s, when we are all chest-thumping and Evil-Empiring and whatnot, was super important to have, a real perspective. That continued on. Obviously, I’d gotten an extreme dose of it being in the Soviet Union itself, but it gave me a window to think about politics and priorities and policy and a lot of things in a different way.

You know, the other experience of Oxford that was purely personal and one of those wonderful serendipitous moments. I’m a J.R.R. Tolkien nut. There are figures on that upper shelf that are from his books. So, it turns out that Merton was one of the colleges he was at. Some of his manuscripts are in the library there. The garden of Merton College has some trees and figures that, at least folklore has it, inspired some of his characters. But then, the one that creeped me out, in a positive way: I’m sitting in my first-year rooms on 25, Merton Street and my so-called ‘Scout,’ housekeeper, is cleaning the room. I had this wonderful scout, and she and I used to talk a lot. I guess I had brought some of my books with me, or maybe I had bought a new set in England, so, there’s Tolkien up on the shelf. And she goes, ‘Well, of course, Mr Olson, you’ll be knowing that Professor Tolkien, these were his rooms when he passed.’

I’m, like, ‘What? He lived here?’ I was absolutely gobsmacked. So, then, when my sister visited, Karen, the one who is two years younger, that settled it. We had to go do a pilgrimage up to the cemetery in Wolvercote where he and his wife Edith were buried, and we did the pilgrimage. So, for me, Merton College was also this connection to history, personal history as well as greater history. The other story that reminds me of, and this is a wonderful thing for students to do. It’s worth looking into the history of the college you go to. I remember the moment when I was sitting in the library, the old library, at Merton College, and I’m looking around at the stone walls and it occurred to me – I was doing some of my old Russian history reading – that there was a student sitting there, like I was sitting there, doing whatever they were doing, at the time that Genghis Khan was raiding Moscow and the steppes of Russia. That place, it was 1264. I mean, it boggles the mind, right?

RW: It does.

EO: The other piece of history is part of my relationship with the English students. I loved it, I loved the teasing. It was good-natured teasing, by and large. Like, the people who really didn’t like Americans didn’t talk to me at all, but that’s not what I experienced. I felt very welcome there in general. But there was a lot of teasing. I don’t know if you would call it historicism, but studying history at Oxford, the history people would be very proud of telling you that if something didn’t happen at least 500 years ago, it’s not really history. I would get into this a lot because I was doing Soviet history, and then the medievalists around me and other people: ‘Well, that’s not history, that’s current events.’

So, anyway, part of the teasing then would come with, you know, ‘You colonials.’ We would be the colonials, which I always thought was amusing, and ‘You’re so young, etc, etc.’ And so, it gave me great occasion, drawing on the family history I shared with you earlier, I said, ‘Huh. So, let’s go back here and let’s talk about the history of the British Isles.’ And so then, I, for the first time in my life, consciously adopted my Viking heritage. In these discussions, I then would pull up my volume and say, ‘Well, it’s interesting to see where agricultural practices came from. Oh, it turns out, you know, it’s the Viking invasion of 800 AD you can thank for this,’ and then I would go, ‘You’re welcome.’ ‘You want to get historical with me? Let’s talk about colonies, okay? As you would say, let’s talk about real, deep history.’ So, anyway, all of that is a long, roundabout way to say it was just a wonderful expansion of horizons, different ways of thinking about home. I love the history of the place. I would go to London on weekends, listen to music and go to museums, and other weekends, for almost no money, I could hire-, there was a little, family-owned car hire, as they called it, rental car place in east Oxford, and I would just rent a car and just drive.

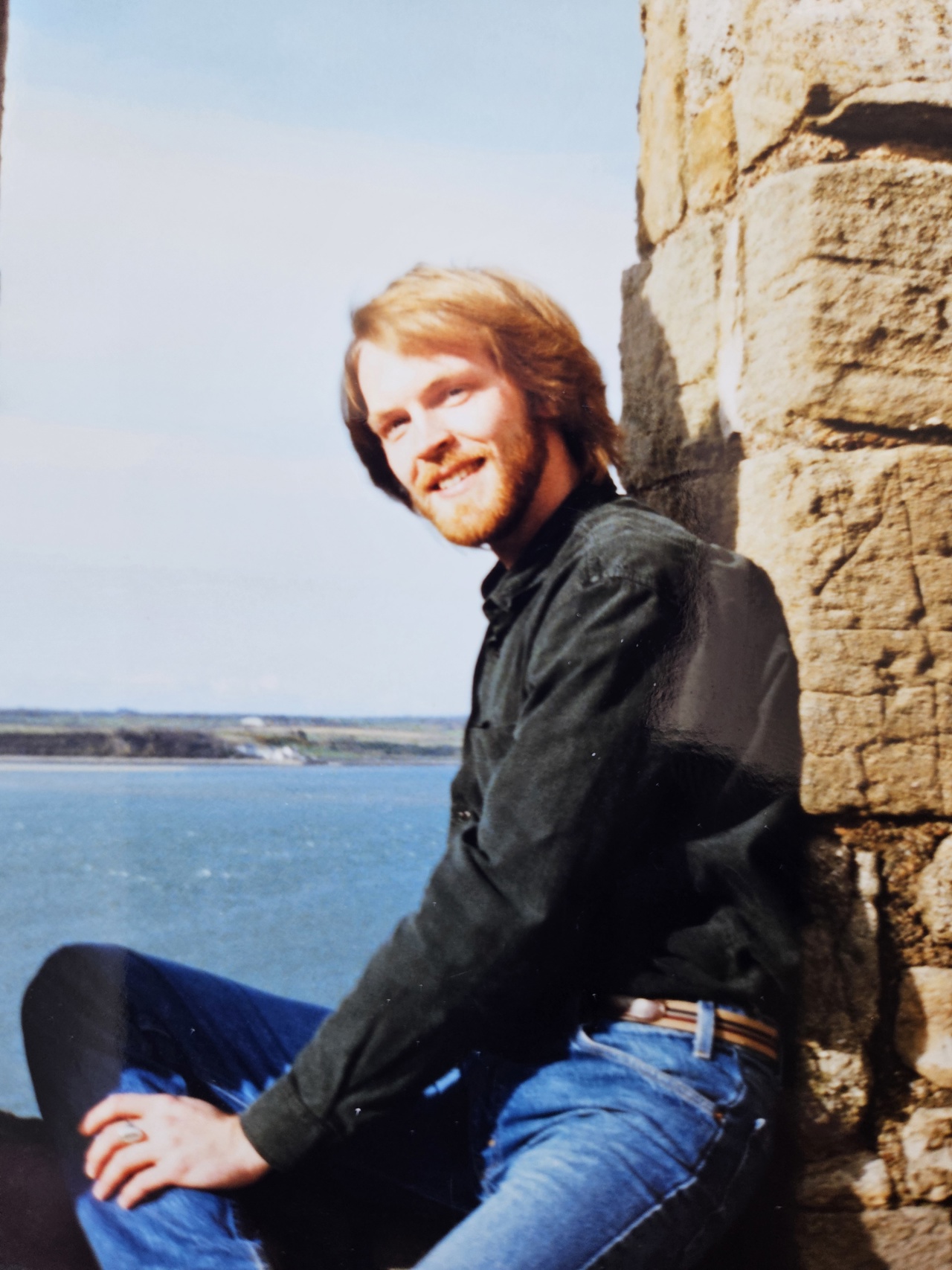

Go to Wales, go to northern England, and no agenda, no reservations. Just drive until it got dark and then go to a pub or an inn and say, ‘Are there any rooms here?’ and just explore, and I just loved it, absolutely loved it. I would go back. It made that kind of impression on me, ‘This is a place I could live,’ for sure. I did not end up finding it off-putting, maybe because I came from a sort of northern upbringing. I didn’t find the Brits any more standoffish than other people I know. They’re a mix, just like the rest of us. Pretty funny.

RW: There is such a unique way in which you really immersed yourself. That’s not necessarily always the journey, and I really appreciate some of those stories.

EO: I wouldn’t trade them for anything. It’s really getting to know a place. And roommates, people that I met, that stays with you forever.

RW: It does. You have to work at it, though, and I’m sure you put the time in.

EO: Yes. It’s hard, and I don’t stay in touch with everybody, but these are the kind of friends that when we talk, it takes us five minutes and we’re back 30 years.

RW: Yes. That’s really beautiful.

EO: I just think that taking the opportunity to be of the world, that’s what it felt like. And I got to know the Brits, the Kiwis – I lived with a guy my last two years from New Zealand, he’s the one who taught me how to ski. I’d never skied in my life. But we go to Evian, a French woman at Merton, my Kiwi mate, and me. She had a French car with her. Oh, she’s the one who had the place at Evian. That’s the connection. I think it was a holiday thing: instead of going home for the holidays, we just said, ‘We’re going to go there.’ And Andrew, who was my Kiwi roommate, was your classic Kiwi extreme sports guy and had been skiing since he was a kid, and I had never been. Oh, my God. I basically ended up buying a [1:30:00] six-pack of disposable, cheap sunglasses, because I face-planted so often and shattered the glasses. I insisted on keeping up with them, right? Because I’m 20 years old, I’m rubber, I’m indestructible, and I just kept up with them, and that’s how I learned how to ski. Very messy, but very, very fun.

RW: And the world keeps opening up for you. That’s the theme, right?

EO: Yes, exactly. The whole thing. I did research back in the Soviet Union during one of the summers. You know, I grabbed it.

RW: And speaking of grabbing it, you played soccer too, right?

EO: Yes, but at college level, I must hasten to add there. This is a very different thing. Blues, university level soccer, would be way, way out of my league. I mean, like the boats. I also rowed crew at Merton. But this was very old English-, I mean, a quarter of us were putting out our cigarettes on the sidewalk, go play some soccer and then, again, guys with white gloves are bringing out a tray of beers for the end of the game. You know, you’d play a game, drink beer and then light up again. Our conditioning was, some guys would get together and go for a run, maybe once a week. And the crew was even worse. Well, actually, that’s not true, we put some work into it. But that was a real trial because, as you probably know, in rowing, you’re only as good as your weakest member. If someone is catching water with their oar or something, it’s a disaster. And of course, you get into this boat on the river, the Cherwell, first thing in the morning, half of the guys are hungover. But it was just great. I absolutely loved it.

RW: It sounds fantastic. You mentioned that you really just dug in and learned how to be of the world as a Rhodes Scholar in Oxford. Are there any other singular impacts you think that time made on the rest of your life?

EO: I think, on a personal level, I met my best friend there, who is a big part of life right through today. The studying, in some ways the impact could have been even bigger, but history comes and history goes. I ended up working in US-Soviet trade development, but to make a long story short, the mafia takes over the country in the early 1990s and that becomes a lot less amusing, I have not actively used Russian in my work since then. So, yet another zig and zag. In terms of the enduring impact, I think it’s the world education, the political perspective, personal friendships that I had, but not actively using the Rhodes network per se. I think the credential has certainly opened doors. I think I get the benefit of the doubt, which is important to someone like me, who tends to shift course. I’ve very deliberately reinvented myself, periodically, and I think the credential and the broad liberal arts grounding behind the credential is probably the number one benefit I got. And it started at Macalester and SPA, but the Scholarship allowed me to take it even further. It means, in a way, that no matter what you do or what happens, you’ve got some tools and experiences that are helpful. And a way of living in the world that’s just different. I’d like to think more tolerant, a little more able to get beyond gut assumptions and local assumptions and think about the other. Those are the things that occur to me most.

Now that the school is getting more organised on alumni things, that’s come back a little bit, but still not a lot, interestingly. It’s still nowhere near the level that Macalester is able to do, or others. Maybe that would be different if I were English. I mean, it is far away, to be fair to them.

RW: I don’t know. I think we’re slow to the party, but I agree that there’s some momentum. We’ll keep working on that.

EO: Absolutely.

RW: Thank you for sharing. Thank you for sharing that. And I would love to expand a little bit on that non-linear but quite illustrious career that you, once going down from Oxford, started to pursue. You’ve been an expert in the ESG / sustainability field for 30 years now. What was the trajectory that took you there?

EO: So, in some ways, the first phrase that comes to mind is, ‘Back to the future.’ So, as many people will say who get into this work, I had formative early life experiences in the wilderness that planted that seed, that connection to land, to the outdoors. Even though I very much put it aside for many years and became a real urban creature. I was in Moscow, St Petersburg, then New York City for ten years. The only trees I saw were in Central Park. But I had that early seed planted. So,why Russia, in terms of work? I just wanted to go there. So, that first Russia job, I only got because of my language skills. The job happened to be US-Soviet trade development.

When I was at Oxford, trying to figure out what to do with my life. I took one of those personality profile tests, because I honestly had no idea what I should do. I mean, I had some ideas, but very vague ones. Business was at the bottom. I had no background in it. I had no interest in business people that I was aware of. But I wanted to go to Moscow, and business was what was happening, and I spoke the language. So, ‘Fine, I’ll do business. I don’t care. I just want to go to Moscow.’ So, I get there, but the point of that story is, what I saw in the 1990s is, the economy opened, I saw the impact that business and businesspeople could have in the service of things I do care about: profitable business opening the economy, creating livelihood. At a time when we were really worried about mutual annihilation, bringing people together, common cause-, I mean, business is, ‘Hey, you and I could start a business,’ or we can trade. It sounds basic, but I saw business achieve things that I thought were more important. Our poor guys at the State Department, you know, we had these ridiculous foreign programmes, ‘Oh, we’re going to teach democracy to the Russians.’ Like, really? Or, I just saw a lot of government money being wasted and a lot of interesting stuff happening.

So, even when the mafia took over the country, I went to New York City, I said, ‘Huh. Business. Interesting. Maybe I should learn how business is really done,’ because in the Soviet Union, it was politics and relationships, right? We were doing trade [1:40:00] with no contract law and a non convertible currency. It was crazy. So, it was countertrade and barter and political agreements. So, anyway, I go back. This is where the Rhodes connection, played a big role, because I’m sitting there going, ‘Now what should I do? Maybe I’ll go to business school, so I can learn how to really do this.’ And then someone said, ‘Hey, dummy, you’re a Rhodes Scholar. A management consulting firm will hire you and that’s basically getting paid to go to business school. That’s what they do.’ So, I found a group of refugees from McKinsey’s banking practice in New York who wanted to create what they were thinking of as the anti-McKinsey which, being a contrarian person, sounded pretty good to me. You know, a McKinsey for cowboys idea. But it wasn’t the cowboyishness of it. It is that they were looking for ‘Alternative candidates,’ meaning non-traditional. So, instead of just your firm handshake, Harvard Business School economics major, this crazy guy coming home from Russia.

RW: Perfect. Yes.

EO: What a cool way to make the firm more interesting. I think that’s what they were thinking. So, anyway, that’s how I got into business. Once in business – you know, again, unexpected – I caught the bug. I became a partner, very young. We grew like a rocket. I loved problem-solving and ended up staying with it a lot longer than I thought I would. But I got bored, again.

So, by now I’m out in California, been a partner for years, but this idea came creeping in that I’ve got a purpose to what I’m doing that’s more than this, I needed to go back to things I care about. I encountered the writing and work of people like Paul Hawken, who wrote a book called The Ecology of Commerce. Amory Lovins and Hunter Lovins wrote a book in the 1990s called Natural Capitalism. And then, when I was a partner at Boston Consulting Group, I got an opportunity to do a piece of pro bono work. It was the time when the big conservation groups figured out that maybe working with business, as part of the solution and not just part of the problem, on environmental efforts would be a good idea. And so, the pro bono brief we got from Conservation International was, ‘How should we work with business to achieve our conservation agenda?’ So, boom, lightbulbs go off. I go, ‘Wow, I could use these tools to do something I care about? Not just help Charles Schwab make more money next year?’ which I’m not against. Good company. Go Chuck! But-,

RW: Yes. You needed more. I get it.

EO: I wanted more. So, anyway, a lightbulb went off. That was now 1999. Which was very early, but here again is one of those left-turn moments. It was way too early. The economics were nowhere near mature enough for a firm like BCG. I jumped out and did my own work, independently. So, again, total reinvention. It’s 1999. Luckily for me, I’m in the Bay Area, where personal reinvention is not a mark of shame, it's the opposite – freelancing and restarting – and I was embraced. People in the environmental sustainability field were like, ‘Wow, we could really use someone like you. Can you help us with this? Can you help us with that?’ So, anyway, I started renting myself out, basically.

My startup capital was six months of my time. I said, ‘By the end of six months, I at least need to have line of sight to something that could be a livelihood, otherwise I’ll go to plan B, whatever that is,’ but it went better than that. I started making money doing it and then this organisation, BSR (Business for Social Responsibility), the board, came and said, ‘Hey, we would like to build a consulting capability within our non-profit, because now we’re going beyond education. You know, companies are graduating from “What is sustainability and why should I care?” to “How do we do this?” and we need to build a real professional consulting capability to help them figure out how to do this.’ So, by then, it’s 2004/2005 and I’m off and running. 16 years of building that team and organisation, and I never looked back.

So, go figure, right? Russian, chemistry, med school, oops. Not oops. ‘Nah!’. Soviet studies, US-Russia trade development. ‘Nah!’ Management consulting. ‘Nah!’ Environmental sustainability. Now, to me it all makes sense, in retrospect, even though I never would have planned it this way. I use my science every day. International interests - the first thing I had to do for BSR was globalise it, so I spent half my time overseas, building foreign offices, just in heaven. China, Brazil, built an office in Paris, a really wonderful place to be. So that’s where the wisdom, the value of this cross-cutting, full, rich experience came to roost. It all matters.

Now here I am, an independent again, and what I’m building is likely to draw upon all these things together. What I’m looking at in sustainability is the fact that most of the things that we care about require the public and private sector, for example, to work together on shared solutions. It’s not enough for a big company to say, ‘Oh, we’re going to go green.’ You need the right kind of public policy. And the policy-makers, on their side, need to know that business actually supports this. So, I find myself working between the public and private sector, building these ideas and collaborations to help us address mostly climate change-focused actions, both mitigation and adaptation, and trying to figure out what’s worth doing for the next chapter. I’m 60. To the extent I can see anything, it’s one more build in this area. Although the build may be a portfolio. In other words, maybe it won’t be 150% with one thing, it will be two or three. Who knows?

RW: Sometimes you can’t know. And you’ve leaned into that your entire life and career, and it is a really beautiful story of a lifelong learner. I think it’s fabulous. But I’m reflecting on what you shared about the reinvention and the startup and the 16 years to build, and all the travel and long hours that that inevitably took. Did you have a family at that time? And if so, could you speak to that balance?

EO: Yes. Oh, absolutely. So, I’ve got a wonderful wife. She and I met-, so, here’s a great story. So, our respective best friends were married. Past tense.

And when I was living in New York, management consulting, she was at law school, at Harvard. My best buddy Zach from Oxford was doing a history PhD at Harvard and I would go up on weekends to see him and his wife and play. And so, they thought that we would hate each other, so they never introduced us, but Susan invited herself over one of the weekends I was there, and we met: true soulmates from the beginning. I think we met and decided to move in together, two months later or something. And now we’ve been married for 31 years.

RW: Wow. What a cool story.

EO: And so, when we started, we both were working yuppie hours. So, it was always, from the beginning, about finding ways to have that balance. She’s a very serious, professional person. She was a lawyer on Wall Street, doing securities law, and I was in management consulting. [1:50:00] So, basically, from the beginning, we had a deal. We worked insane hours during the week and then we really did connect and spend our time together on weekends. She then went into teaching, got a position at Wharton. So, we had a couple of years of what we called the metro-liner marriage. We had a second apartment in Philly.

I would be usually out of town, on site, anyway, during the week, so it’s not like there was any value in having her sit there. But then, one of us would take the train to the other and spend weekends together. When it was time to have children-, she grew up in San Francisco. She knew there was no way she wanted to raise a family in Manhattan. I think I would have been okay trying, but she says, ‘Let’s check out San Francisco.’ I visited her out here. I caught the bug, and came out to open an office for my consulting firm in San Francisco. She put herself on the market, got a position at the University of San Francisco law school. So, that’s 1996. The end of 1996, we move out here, she’s pregnant with our first daughter.

And so, I’m in the height of management consulting craziness while we’re starting to produce babies. When the kids were babies, we would do split-shift sleeping. So, she would go to bed at eight o’clock, as soon as she was able to pump, and I would be up working until one or two anyway, and I would do the bottles until two, which means the kid, most nights, would sleep until five or six, which means she got to sleep from eight to six, right? And so, I did my shift.

So, that was one thing, to share the load, be there for that. And then the other thing is, even in management consulting – and it became a lot easier when I moved to BSR and was in a different kind of organisation – I did a two-shift work life. So, Monday through Friday at first – work from, whatever, seven, eight in the morning until five, five-thirty. Religiously cut off: five-thirty, I’m done. A little easier to do on the West Coast, because it’s even later on the East Coast, so, that worked. Things would be quieting down. Family for four hours. And then, second shift: put the girls to bed and then work at the computer in the evening. So, we could always have dinner together. That’s always been a rule. So, get my couple of hours with family. And then, the other thing I’ve been able to do since 2001: don’t work weekends.