Born in New Haven, Connecticut in 1952, Elliot Gerson studied at Harvard before going to Oxford to read PPE. Alongside a distinguished career in law, in business and in non-profits, he has also served for twenty-five years as the American Secretary of the Rhodes Scholarship, and counting years as an Assistant American Secretary and as a Committee Secretary, forty plus years of selection leadership. He is currently executive vice president at the Aspen Institute, where he is responsible for its Policy Programs, Public Programs and its International Partner Institutes. This narrative comprises excerpted and edited highlights from a much longer interview with the Rhodes Trust on 1 February 2024.

Elliot Gerson

Connecticut & Magdalen 1974

'It was not a childhood of privilege, but we were very happy....'

New Haven is where it all began for me. My father was a late teenage immigrant from Poland. He came to the US in 1938. My mother was an Irish orphan. They met in university and fell in love, despite their different backgrounds and religions. They just viewed each other as American. That’s what they aspired to be and that’s what they were. Our part of Connecticut was quite rural, and my hobbies were focused on being outdoors – sports, but also wandering in the woods, fishing and biking. It was not a childhood of privilege, but we were very happy....

I was also lucky to have inspirational teachers at my small and regional public school, including one who really cultivated my interest in American history, politics and public affairs.... I had so many interests, and still do, but from a pretty early age my career focus was on doing something political or public service related.

On applying for the Rhodes Scholarship.

When I went to Harvard, I wasn’t sure whether I wanted to specialise in science, humanities or in social sciences. As time went on, I became more and more interested in economics.... The night before my final Rhodes Scholarship interview, I got a call to say that I had been awarded a Marshall Scholarship to read economics or a DPhil at Cambridge. I think maybe that gave me an edge, because I went into the Rhodes interview feeling unusually relaxed. I knew I was going to England to study on someone else’s dime either way!

Seeing the application process from the other side in all my years as American Secretary has been fascinating. I’m struck by how much the essentials of the process have remained the same. We’re still choosing people who have the potential to be leaders and to make a difference for others in positive ways, but, and essentially, through the filter and experience of one of the world’s greatest universities. So, academic ability is fundamental, but it’s not enough.... The selection process is looking for well-rounded excellence, with exceptional foundational academic ability suitable to Oxford, alongside an ambition that is very other-directed.

Some things are different now. For example, in the administration of the Scholarship, we worry today about things like Artificial Intelligence, and we are aware of all the guidance that students get in applying and writing their essays. We had none of that. I don’t think even my mother, girlfriend, or roommates ever saw my essay. And surely not an Advisor. I probably wrote it in a few hours, and I don’t think that was different from anybody else. It was just not the drama and the process and the mentored engagement that it evolved to be in many places.

We have done a lot of outreach work to ensure sure selection happens in spaces where people can be comfortable, where they don’t feel excluded. We want to ensure that the Scholarship feels accessible to those who could otherwise think of it as something they might not aspire to. The question, however, of a “balanced” or “diverse” cohort overall is not something that we consider when selecting Scholars. We choose people on the basis of how they, as individuals, fit the criteria. But the work of building a cohort after selection does now happen much more consciously at Rhodes House. Once Scholars are in Oxford, Rhodes House makes sure they can acclimatise academically and in every other way, and in ways not familiar to earlier Scholars.

'Being immersed in Oxford’s history and culture'

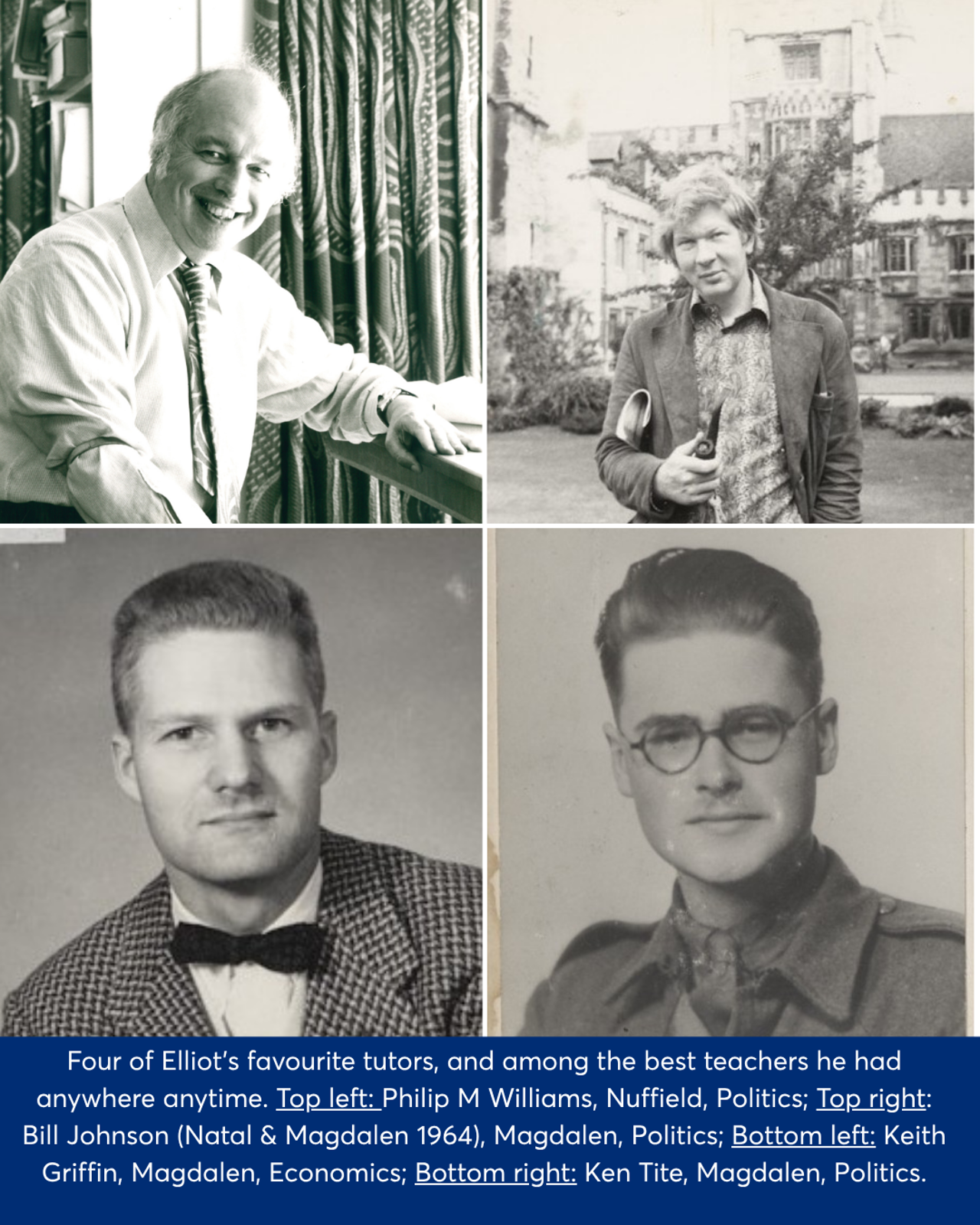

I would describe my time at Oxford as perfect. I loved my college life, I loved my tutors. It was magical, and I say that knowing that it’s not magical for everybody. I was very privileged in my education both at Harvard before and afterwards at Yale Law School, but I have to say that my educational experience at Oxford far surpassed both and that was about the sheer quality of the tutorial teaching...I still think often about some of my favourite tutors, though in particular the extraordinary Philip Williams of Nuffield (I was "farmed out" to be with him), who used to visit me on his trips to the US in the decade following my tutorials; Bill Johnson (Natal & Magdalen 1964), also politics, of Magdalen, whom I visit as a lifelong friend in Cape Town, and who still "tutors" me via his emails and his brilliant writings in the South African press; Keith Griffin, Magdalen, economics and who became the College President; and the wonderful Ken Tite, Magdalen's dean of sorts of Politics dons, whom I was lucky to have just before his retirement and whose family I also got to know.

I also made wonderful friends amongst a diverse and international group of people, many of whom were not Rhodes Scholars – Scholars weren’t brought together in Rhodes House then as they are now. And of course, Oxford is such a special place. There’s something about it that’s evocative of memory because its buildings and spaces just don’t change much. You know, when I go into Magdalen and walk around Addison’s Walk or through the cloisters, obviously that hasn’t changed since the fifteenth century. But even just the town of Oxford, you walk down Merton Street or New College Lane and it’s the same as it was when I was there fifty years ago, and centuries ago. The only things that change are the quality of the shops and the food; they get constantly better but sadly more expensive of course....

I had married at the end of my first year, and my wife and I spent a lot of our free time getting to know this part of England, especially Oxfordshire, the Cotswolds, London, and that was wonderful. Travel was expensive, so we didn’t go abroad that much, but as I often say to Rhodes Scholars now, the Scholarship doesn’t have to be about travelling all over the place. Immersing yourself in life in Oxford and England means that you can get to know a country’s history and culture in a way that very few people ever get to know more than their own.

One other thing I would like to mention about my days in Oxford was how important sports were to me. The amateur traditions, and the complete lack of big-time sports apparatus and culture that I think distorts American higher education so terribly, are so conducive to enjoying sport for its true and wonderful values. I took up rowing and loved it all six terms I was there, and still proudly have the oar I won on my wall. I also played squash for my college, as I had in the United States, and learned to play cricket with my MCR team. Finally, and maybe most fun and with lifetime implications, I took up the wonderful and ancient sport of real tennis and played matches all over England and not just against Cambridge for the University, but in three cities in France as well.

When I’m asked to give advice to Scholars now, what I emphasise is an extension of that idea: don’t rush to get to the next thing. Enjoy what’s around you. Relish what you have and take advantage of it.

'A turbulent time in many ways'

So, for me, Oxford was a superlative experience. That’s not to say, though, that it wasn’t a turbulent time in many ways. There was a lot going on in American politics (we would all rush into the Middle Common Room in my college, Magdalen, to grab the latest copy of the International Herald Tribune so that we could learn what had happened in the latest primary – or whether the Red Sox had won!) ..... We stayed connected to home and family by writing letters. There were coin-operated phones in the Middle Common Room, but you’d hardly ever have the right shillings and who knows if there would be people on the other line.

I’m ashamed to say that the moves afoot then in the early to mid-1970s to open the Rhodes Scholarship up to women didn’t particularly register for me when I was at Oxford, and I’m embarrassed about that, particularly when I think back to a Harvard contemporary of mine who actually refused to apply for a Rhodes Scholarship on the grounds that the Scholarships were not open to women. I learned later, when I became Assistant National Secretary under Bill Barber, just how much work had gone on behind the scenes to change that.

And there were other things that were difficult about life in Oxford then for some people. I had a very close English friend in my college, Stephen Webster, but all the time I knew him during our two years at Oxford, I didn’t realise that he was gay. And there was another mutual friend of ours who was also gay, but again, he chose to hide it, and it was very sad. It’s one of the biggest changes, I think, between life then and life now. I often think of Stephen. He went to the US just as gay liberation was beginning, but it was also the beginning of HIV and AIDS. He came out and, sadly for me, felt that he had to leave behind his straight friends from his earlier life and then, a year and half later, he was dead. It was tragic.

'The greatest antidote to cynicism or pessimism'

I don’t think there have been many days in my professional career where my experience in Oxford hasn’t been relevant in a direct sense to what I’ve been thinking about. To this day, my interest in and understanding of European politics or how different governments work, or economics, or political theory in terms of how we think about the state of the world and about the state of democracy – all those things are affected by the academic work that I did at Oxford.

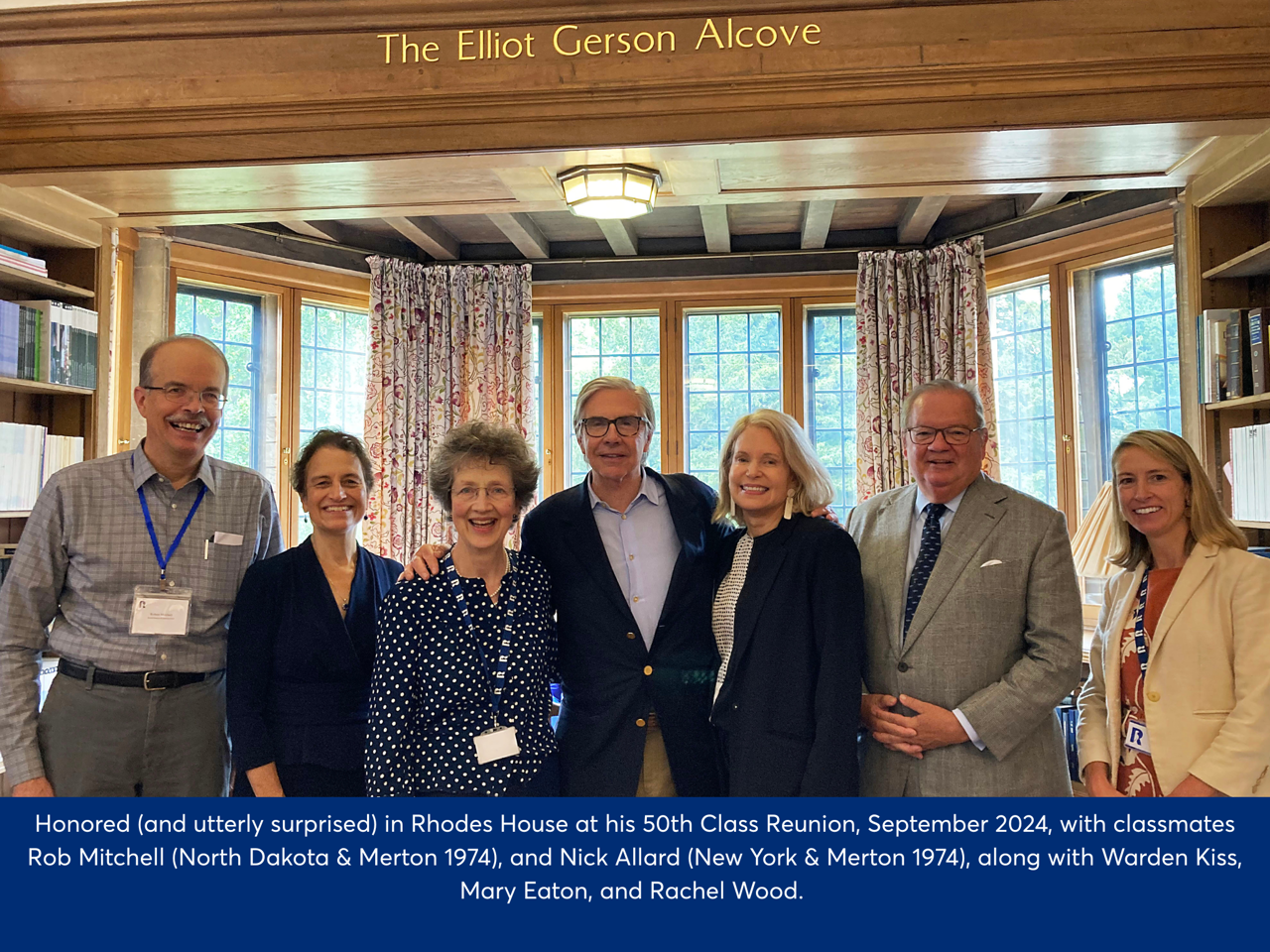

For me, the greatest impact that the Rhodes Scholarship had was that it allowed me to hold the position of American Secretary for a quarter century. Helping the Trust in this very privileged volunteer way has been incalculably significant and valuable to my life. I would say that the opportunity to meet young Rhodes Scholars is the greatest antidote there is to the cynicism or pessimism that can sometimes accompany ageing (I have ten grandchildren now too, which also helps!). The world can be a depressing, scary place, but being around cohorts of young Rhodes Scholars who are dedicated to making change in significant ways gives me the greatest hope I could imagine for the future.

I’m lucky, because in the last 20 years, I’ve been involved in non-profit roles that provide opportunities to engage meaningfully in the things I care about, which mainly relate to opportunity and equity, across the US and the world. One thing that I’m especially proud of is the work I’ve been involved in for the last 15 years in Ukraine. I brought the Aspen Institute to some work there and that led to an Aspen Institute Kyiv being established. It’s become one of the most respected civil society institutions in a challenged country that is trying so hard to build a democracy in the face of extraordinary evil and aggression, and with a history of poor governance and corruption from its communist days. We’ve expanded recently into Colombia too, a country of beauty but with great wealth disparities that’s trying to build an equitable democracy from very difficult circumstances.

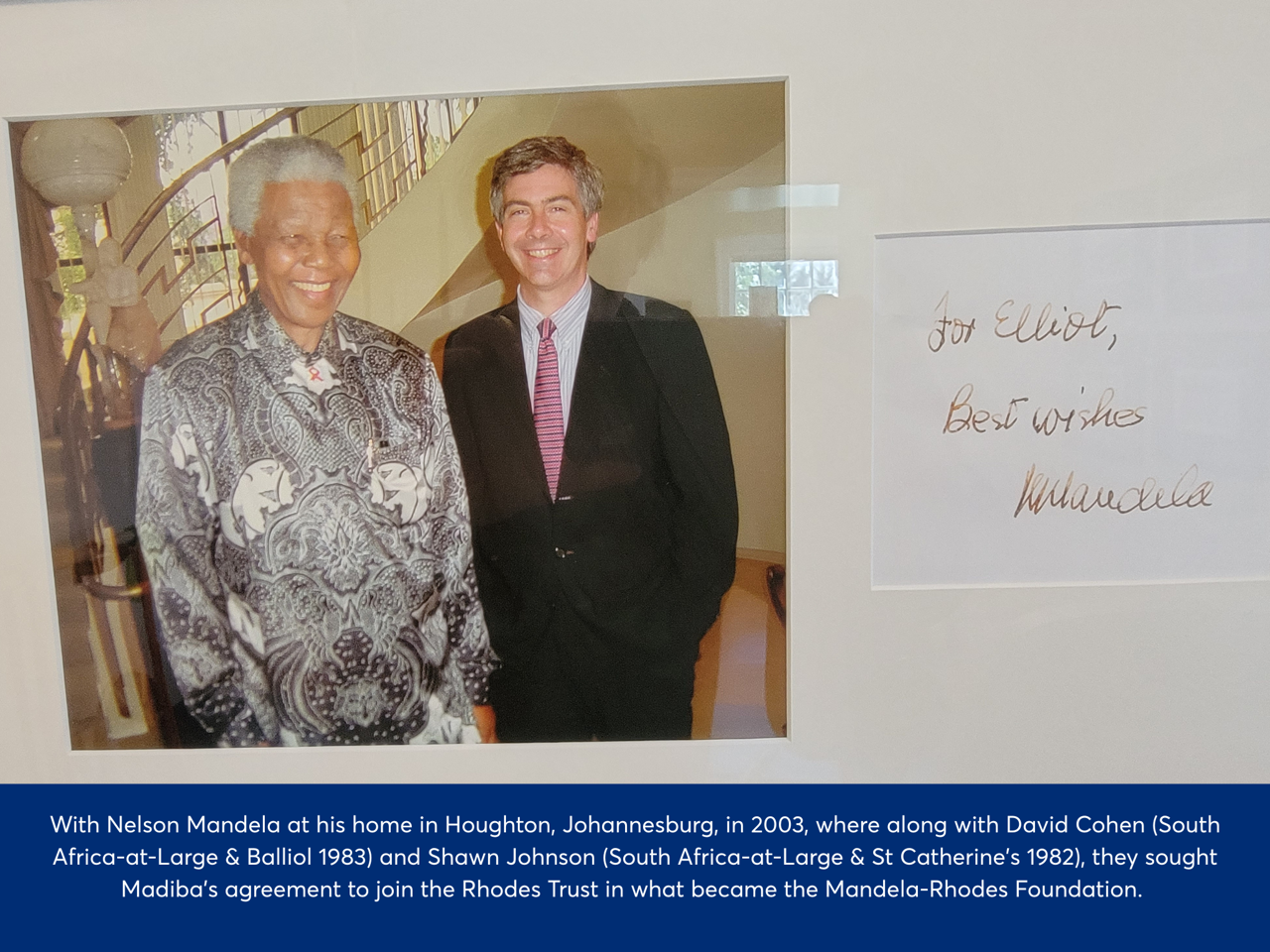

On meeting Nelson Mandela.

The goal of advancing equal opportunity is something I’ve strived for in my work for the Rhodes Trust as well, and I’m especially proud to have been involved with the Mandela Rhodes Foundation from the beginning. It was an extraordinary privilege to meet Nelson Mandela as part of those early discussions...I don’t think there is anyone I have ever met of greater impact. We were in South Africa to speak about whether he would consider having his name linked to that of Cecil Rhodes, and there were many people who were deeply sceptical about whether that could ever happen. I was amazed by how quickly he accepted the notion of a connection, and we celebrated the Foundation’s 20-year anniversary this past year...... For several years recently, I’ve been the chief judge for an entrepreneurship prize, sponsored by David Cohen (South Africa-at-Large & Balliol 1983), that is open to Mandela Rhodes Scholars and Rhodes Scholars for their work that makes a difference in Africa, particularly for those most marginalised.

It’s so important to me that the Rhodes Scholarship remains as special as it is, bringing extraordinary people from all over the world to have that fundamental experience of being a student in another country, another culture, in a university of renown. That, I think has great meaning and value and should last in perpetuity.

Transcript

Interviewee: Elliot Gerson (Connecticut & Magdalen 1974) [hereafter ‘EG’]

Moderator 1: Rachel Wood [hereafter ‘RW’]

Date of interview: 1 February 2024

RW: My name is Rachel Wood. I am with the Rhodes Trust conducting a Zoom interview with Elliot Gerson (Connecticut & Magdalen 1974). It is 1 February 2024. From 1998 to 2023, Elliot was the American Secretary of the Rhodes Trust, administering the 32 annual United States Rhodes Scholarships to the University of Oxford each year. The Rhodes Trust is absolutely indebted to Elliot for this unrivalled contribution to our core mission. And now, during the 120th anniversary of the Rhodes Scholarship, Elliot is helping us launch the first ever comprehensive Rhodes Scholar oral history project. We are so grateful to you, Elliot, for this gift to the community and to the future Rhodes Scholars, and I’d love to get started with just a few formalities and then turn it over to you. So, Elliot, do I have permission to record this interview?

EG: You do.

RW: And can you please spell your first and last names for me?

EG: Elliot Gerson

RW: Thank you. And finally, where are you recording this interview from?

EG: In my house, in Washington, DC.

RW: Fabulous. Okay, now, if we can, Elliot, I would love to get us started by going back to the beginning. Can you tell us a little bit about where and when you were born?

EG: Well, I was born almost 72 years ago, in New Haven, Connecticut, where my father had been in graduate school. So, New Haven is where it all began for me.

RW: And tell me about the family you grew up with. Where did your ancestors come from, and then how did your parents meet?

EG: Okay. My father was a late teenage immigrant from Poland – he came to the United States in 1938 – and my mother was an Irish orphan. They met in university and fell in love, despite their different backgrounds and different religions. And really, a wonderful story. They just viewed each other as American. That’s what they aspired to be and that’s what they were and so the differences in their backgrounds really didn’t matter. And in a sense, they were both almost alone. My father’s mother died shortly after I was born. My mother never really knew her parents. Her mother died in childbirth but she had aunts and uncles and cousins in New Haven and it was a tight family. I was the oldest of three children. My childhood continued to be in Connecticut, where my father, after his doctorate at Yale, spent his career teaching at the University of Connecticut. And my mother was a geriatric social worker in the latter part of her life, and tragically died too young herself. But that’s my family.

RW: Tell me more about your other family members who lived nearby, and what was your community like outside of your family as well?

EG: Well, again, I lived in a little college town in Eastern Connecticut, and it was a wonderful childhood. It was a college town amidst a rural, working-class area of Connecticut, actually a very large geographic area funnelled into the small public school system. So, I’ve often thought of all the benefits of coming from an environment like that. A lot of people associate Connecticut with the part of the state close to New York with a great deal of wealth, but I was from the corner of the state that was quite different. And you know, this is a year of anniversaries, my 50th anniversary of arriving in Oxford. Also, of course, my 50th anniversary for my college class. And then, not too long ago, twice delayed by COVID, of course, my 50th reunion for my high school. So, that was a fascinating experience, and a bit of depressing experience too. Again, reflecting the demographics of my childhood home, you know, to find that many of my classmates had already died at what I think is a very young age, and then to look at the very different life paths of those who went on to university compared to those who did not. And essentially, it was a direct reflection of what I think we’ve experienced in at least my adulthood, with widening inequality, widening gaps in opportunity, and even in lifespan. And interestingly, many of my closest friends in high school were those who frankly did not go on to college and did not have a very easy life.

RW: Right. Tell me, then, more about young Elliot before the high school years and the hobbies that you might have had as a kid in your neighbourhood.

EG: It was quite rural and my hobbies were very much focused on the outdoors, like most young boys. Sports was a big part of my life, but also just wandering in the woods. I could walk behind my house for what seemed like miles, probably was less than that, through farmland and fields with cows and streams and ponds that were isolated and not developed, and I would fish and bike. Otherwise, a typical boyhood of the time with sports and Boy Scouts and eventually girls. So, it was a wonderful childhood, happy family. I was close to my younger brother and sister, and I consider myself very lucky even though it was certainly not a childhood of privilege.

RW: That’s wonderful. And when you moved into your high school, what are some reflections about those years. Did you have any influential teachers, classes or activities that helped define you?

EG: You know, I haven’t thought about that much. I still remember the names of my first and second and third grade teachers, but I think some of the most influential teachers I had in high school. For example, Mr Marlin had a lot to do with cultivating my interest in American history and politics and public affairs. Of course, I also got some of that at home because my father’s academic field was political science. I was very engaged in my community and in my school. Probably like lots of people who ended up Rhodes Scholars I was president of my high school student council and enjoyed those kinds of activities. But I’d say, you know, a typical small public school experience, with some wonderful teachers. I remember my French teacher very well. My peak competency in French language was as a high school senior. You know, one of the disadvantages of being American [10:00], even with all the travel I’d do around the world is that more and more people speak English, and I really kick myself for not keeping up with languages, especially now that we have a home in Mexico. I’m a Mexican permanent resident, and my Spanish is grossly embarrassing. I keep thinking if I ever retire, I will lose that embarrassment and learn to speak Spanish. But no, I had dedicated high school teachers I remained close to for a number of years. I remember I also had a very good physics teacher. I was torn between science and social sciences as I went to college, in part because I had great teachers in chemistry, biology and physics there. I think I benefitted considerably by the fact that even though it wasn’t a rich area, it was a college town, so we had, I think, exceptionally good teachers. But it was a great time.

RW: It sounds wonderful. And tell me, as a high school kid, did you have dreams? I mean, you were clearly a dedicated student, who went on to Harvard. As a high school kid, what did you imagine yourself growing up to be? Did you have dreams or goals at that point in your life?

EG: Now, that’s very interesting. You know, obviously, I don’t want to show any false humility. I was a good student, but I didn’t identify myself as a good student. You know, think about high schools and the ‘culture’ and sociology of high schools. It was much more important to my self-image being an athlete than being a student. But as far as goals go, getting back to the public service aspect of things, and again, with family influence and my parents’ deep engagement in local and state politics, from a pretty early age I aspired toward a public and political career. That’s probably what most of my friends would have said, even though I remember, I think in my high school yearbook, I said, ‘I plan to be a marine biologist,’ or something like that. I scratch my head and I say, ‘What was I thinking?’ But, you know, I still scuba dive and I like swimming around with fish. But I think I was clearly on a political, public service-related course from an early age, but was always distracted by so many other things that interested me.

RW: Right. What were your sports, particularly in high school?

EG: Oh, goodness. In high school, again, I was advantaged. You know, I can’t pretend that I was a world-class athlete, but in a small town, although it was a regional high school, I was able to play on varsity sports. I played soccer. Our school was too small to have a football team. I’ve always felt that was lucky. I think soccer is a much better sport, and I was captain of my team. I played basketball, and I played baseball as a young boy. That was my favourite sport, but then I started playing tennis and couldn’t play both in the same season, so I stuck with the tennis team. I played pickup football in people’s back yards. I would say soccer was really my main sport and tennis was the sport I played the best. I had some aspirations to play tennis in college, until I realised that there was no way I could compete at that level.

RW: Well, let’s move on to college. Let’s talk a bit about your undergraduate years at Harvard. Tell me about successes and accomplishments and frustrations and challenges.

EG: I loved college. Harvard was a very late idea. You know, my father had gone to graduate school at Yale, and I was born in New Haven. I always thought I’d do that. It just happened that I had a cousin on my Irish side – not a close cousin – who went to Harvard on a football scholarship. And if anything, growing up in Connecticut, Harvard would be the last place I wanted to go. But I spent a weekend visiting him as a junior, he and all of his football roommates and again, reflecting on what kind of interests I had, they seemed to be having a hell of a good time. I said, ‘Gee, I think I would enjoy being here.’ So, I ended up going there, and I was very lucky with interesting roommates and lucky assignments and teachers. I had a freshman seminar in literature and politics with a wonderful, iconic professor and I became interested in too many things to possibly study. I couldn’t decide if I was going to be a biologist and I thought of medical school for a while. With the inability to decide what I really wanted to do, I majored in the history and philosophy of science.

So, I had a combination of science and social science, and then became very interested in economics. And, you know, if we could have had a ‘minor’, I would have minored in economics, and, indeed, ended up applying to graduate school in economics. And we’ll probably come to this, but I often think about how careers change and interests change and how much luck and circumstance influences life. For example, I was awarded a Marshall Scholarship just literally days before my final Rhodes interview, and I had already been admitted to Cambridge University to do a PhD in economics, and goodness gracious, if I had done that, who knows what I would be doing today? I’m sure I’d still be having fun, but it would have been very, very different. Anway, I had a great time in college socially, wonderful friends, a wide variety of academic interests, I continued to play sports for two years, including intercollegiate, until I couldn’t really compete at that level anymore. I was involved in student government, ran things in my own housing complex. But at the same time, I was also in their fraternity, called ‘clubs’ at Harvard, and I was president of a club. It is embarrassing to think back to most of the clubs and how opposite of inclusive they were. You know, nothing that I would have put on my résumé, but I had a wonderful time, and in retrospect, feel like I played a little bit of a role in opening that world up to people like myself who never would have been part of it. Overall had a great time.

RW: Tell me more about that, though, about your experience in the clubs and your role in opening them.

EG: I think many of my best friends in college probably weren’t even aware I was in one of these, fancy, rich-looking institutions that the Harvard clubs were, and I certainly hadn’t been aware of them. But again, some of my friends in my freshman year, had been from families whose fathers – and this was, of course, all men, which we may come to in other contexts – had been members earlier, and had gone to fancy private boarding schools, which tended to be the feeders for these institutions, and some of those friends were my close friends [20:00]. They said, ‘This might be of interest to you.’ And lo and behold, I ended up getting involved and loving it and was president of my club. I think I was probably the first Jewish president of any of those clubs, and our club had a history of opening things up in ways-, you know, John and Bobby Kennedy were the first Catholic members of the same club, which shows how strange these institutions really were. But I brought a lot of other people in who also had gone to public schools. I had a black vice-president of my club, who remains a close friend. We also had many members from other countries. But again, also the smattering of the kinds of people one might have associated with places like that, household billionaire names. Another one who was the son of a major Central American dictator. So, it was a very unusual experience.

It was a small part of my Harvard life, but, you know, I’d be dishonest to say it wasn’t something I enjoyed, although I spent much more of my time in my Harvard house, which of course were modelled on the Oxford colleges, and in a wide variety of other activities. I was on a university-wide elected student organisation focused on undergraduate education. And it was also an interesting and challenging time to be in an American university. I never really personally felt the pressure of the draft, although I had a draft number. My cohort, I don’t think any of us ever felt that we were going to go to Vietnam, unlike those two to five years ahead of us. But, you know, there were major riots my freshman year, and takeovers of university buildings, and whether the issues were Vietnam or civil rights, or divestment from companies investing in apartheid South Africa, I was involved in all those kinds of things. Again, I was also there at an unusual time. I was the last all-male Harvard freshman class, Harvard Yard, that is. And then, Radcliffe was still a separate institution, but over my time there that, thank goodness, became modified, though not nearly as much as it was subsequently. I was a walk-on on the squash team which was, culturally, not something I’d ever really been exposed to before, but I’d been a reasonably good tennis player and played both my first two years until there was enough competition far better than I was. But I loved that and continued to play that at Oxford, actually.

RW: Oh, did you? Wonderful. And so, during these what sound like very invigorating and yet slightly tumultuous times at Harvard, did you have any influential mentors that you reflect on, or was it mostly your friend groups that really impacted your life during that time?

EG: I would say it was mostly my friends who impacted my life, but I had some professors who had very significant impact as well, of an intellectual nature. Stanley Hoffmann was an extraordinary man. I was privileged to take a freshman seminar with him, and it got me quite interested in political philosophy. And then, one of my favourite classes was taught by a man – most of these great people have passed away, sadly – Seymour Slive, who was a great art historian, and I developed a lifelong interest in art. One of the best classes I ever took was northern Renaissance art. And wonderful teachers in my concentration, which was, again, history and philosophy of science. My particular interest was the history of evolutionary biology. But again, I consider myself very lucky to have been influenced by people like that, but also, just to have a wonderful group of friends. And, you know, sadly, at the time, they were all male, although I did have – and I must mention, because she was so significant in my early life – my high school sweetheart was at college nearby, and so, I had a girlfriend throughout that period and, indeed, we got married after my first year at Oxford. So, I knew a lot of women, really, through her and her friends, and they became very good friends. But otherwise, you know, Harvard was a much too male institution.

RW: But it sounds like you made it such a well-rounded experience for yourself. And now I want to jump to a comment you made earlier, which is that you have received a Marshall Scholarship towards your final days at Harvard and were planning on going to Cambridge and studying economics, and yet you also applied for the Rhodes Scholarship. Tell me about that decision and those memories.

EG: Well, I had been aware of Rhodes Scholarships and for some time, I wanted to study in England. I didn’t know about the Marshall Scholarships – which are wonderful, and then, in my subsequent life, I’ve enjoyed building close relationships between the Rhodes and the Marshall fellowships and administrations. But in a funny way, I think the fact that I had this phone call from the British Consul General in Boston literally the night before my Rhodes final interview may have given me an edge, because I was so relaxed going into the interview, because I knew that I was going to England on someone else’s dime either way. But yes, I remember applying and there are things that are just so different. I mean, for example, my Rhodes essay. You know, we worry today, in the administration of the Scholarship about things like Artificial Intelligence, and we obviously are aware of all the guidance that students get in applying and writing, and of course, we had none of that. I mean, I don’t think my mother or girlfriend, or roommate ever saw my essay. I probably wrote it in three hours one day, and I don’t think it was different from anybody else. It was just not the drama and the process and the mentored engagement that it seemed to evolve to be in many places. But I was excited at the possibility. I certainly must say that unlike students at institutions without the historical number of Rhodes Scholars, it’s hard to go through Harvard and be a reasonably good student without knowing about the Rhodes Scholarships.

So, you know, it was in my mind and I was encouraged to apply and there were many people who could serve as referees. And I’ve always been aware of that advantage that I had, again jumping ahead to my days as the American Secretary at the Trust. For example, I thought if I had stayed on and gone to where my father taught, at the University of Connecticut among thousands of students and without ever having had a Rhodes Scholar until just maybe eight or ten years ago, I’m not sure that I would have even thought of it. And so, that’s one thing that I think we’ve made just enormous progress in-- Not changing the criteria or the selection standards in any way but widening the funnel in equitable ways. But getting back to New Haven, I had the choice of applying in Connecticut or Massachusetts. It didn’t really much matter. We were in the same district, but [30:00] I applied in Connecticut, and in another life, I actually changed the tradition of the state interviews being in New Haven, because having not been associated with Yale and having the interviews in New Haven with a Yale person as secretary of the committee and Yale people dominating the applicant pool and probably – I don’t remember everyone sitting around the table interviewing me, but my guess is probably half had a Yale affiliation – I felt a little bit uncomfortable.

And jumping ahead, one of the things I did as American Secretary was issue some guidance that interviews never be in places that could make anyone uncomfortable because of either an institutional association, or that’s either socially or economically or racially exclusive in a way that could make a candidate feel uncomfortable. Because, you know, the process is so subjective, even being in an environment where one is not comfortable and all of one’s fate in the competition is depending on the questions you happen to be asked over a 20- or 25-minute period, whether you’re comfortable or not comfortable can have very serious implications. In any event, somehow I managed to survive New Haven – at that time there was a two-stage process – and then going on to the interviews in Boston, which were not at a Harvard-related institution, thank goodness. But again, getting the phone call from the Marshalls the night before, it was a much more comfortable process than I thought it might have been. But a funny thing – I’m just remembering this – there was a classmate of mine in Quincy House with me who received the same phone call the night before and his father was actually someone I had gone to lectures from, a rather well known economist named John Kenneth Galbraith. He told me that morning, before the Rhodes interview, that he was going to withdraw from the Rhodes and take the Marshall, which is something that happens very, very rarely. But he made the decision and then, just an amazing coincidence, as I got on the subway, the T, from Harvard Square to go into my interview in Boston, it was all very crowded. You can’t make this up, but it’s true, I came in, and I think the only time I ever saw him except in a large lecture hall, who is there but is father, John Kenneth Galbraith. And I’ve forgotten how we got into this conversation, but we did, and I said what I was doing, and he said that he thought his son had made a mistake and that he should have gone on. And interestingly, Jamie’s the son’s rationale was that he thought at that time, and arguably at that time it may have been the case, that the Marshall had the academically more distinguished reputation, at least in Harvard circles, than the Rhodes, with more of its all-rounded reputation, and he thought, as someone who planned to be a professional economist himself, that the Marshall would be a stronger indication to the public about his intellectual qualities and there would no element of potential nepotism or favouritism or fame that might have otherwise been the case. So, in any event, he was very happy to do the Marshall and has had a very distinguished career. But yes, that’s my recollection. I remember a lot about my Connecticut interview, less about my Boston interview, although I did end up putting some people on selection committees many years later, at least one of whom had been on my selection committee.

RW: No kidding? That’s fantastic. But you do remember being much more at ease, because you knew you were going to the UK on someone’s dime, potentially?

EG: I think so. But, you know, having those experiences, I think most of us never forget, whether it’s the reception or the interview or the other people in the room. But I was very sensitive when I became responsible for some of these things about the settings, the ambience, the balance of the committee, really from my own experience many years earlier.

RW: And do you remember, walking into that interview, did you have a clear idea of what you wanted to do for the rest of your life at that point, or at least for the next five to ten years?

EG: I still thought that my career was most likely to be in government or politics, and so my thoughts about Oxford were to do PPE and then probably the default post-Oxford, if you wanted a political career, was law school. So that’s what I assumed I was going to be doing, and then I went off to Oxford.

RW: You went off to Oxford. So, let’s talk about that. Let’s talk about that infamous transit to Oxford with other Americans in the class of 1974.

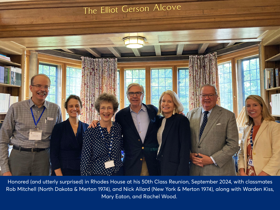

EG: Well, it was infamous because I screwed up. Well, there was not much I could have done about it. The American Secretary at that time, Bill Barber (Kansas & Balliol 1949), who subsequently became a very good friend – when I was at Yale Law School, he asked me to be his Assistant American Secretary. But he had the custom of asking a member of the American class to act as, essentially, the travel agent to the class and make the arrangements for the sailing, which all the classes before us had done. And I’m not sure why he asked me. I think because he lived in a small town in Connecticut not too far from where I did. You know, there’s no other reason for it. But my luck, our class was the first one to miss the boat, because we had a booking-, there were really only two options, the QE2 and the SS France, and I think I’m right in remembering that the QE2 – whichever one we had a booking on – became unavailable, and then the other one was also unavailable, so we ended up having to fly. In one case, I think the QE2 was commissioned, somehow, in connection with the Falklands War, and I think the SS France, you know, was stopped by a strike, a labour action. But in any event, I failed in that endeavour. We had dinner in New York, but we never sailed together. We got on an airplane and so, we never bonded in the way that our preceding classes did, or we didn’t begin as bonded, but I think in the years since, we’ve made up for having missed that, and also assisted by, a particularly energetic and skilful Class Secretary, Nick Allard (New York & Merton 1974), who has really engendered an enormous degree of bonding, even if we didn’t have it while we were in Oxford. Actually, one of my other great decisions in life, I was our Class Secretary for our first ten years, and I gave that up, thank goodness, because Nick was far more assiduous and far funnier and far more conscientious than I ever would have been.

RW: So, how would you describe your time at Oxford, Elliot, as a Rhodes Scholar?

EG: You know, it was perfect, actually. I loved it. And again, I had been privileged [40:00] in my education before and after, but it was, for me, magical. And I say all that knowing that it’s not magical for everybody, and I think it’s very hard for those Rhodes Scholars who don’t have a good experience – and there are not many, but there are some. I think it’s important for people, at least within the family, to be candid about it, and we learn a lot about why some experiences are better than others. I think being a Rhodes Scholar and coming back to the United States, people recognised the incredible privilege that it involves. If you really don’t have a great time, it’s not easy and it’s arguably, really, off-putting and, frankly, arrogant-sounding to say, ‘Well, I didn’t like it,’ as some people didn’t. You know, they may not have chosen the right course, they might not have liked their own college, they might have just broken up with their girlfriend, they might have hated the food or hated the weather – good reasons for both. But I loved it, every bit of it, even the inconveniences of Oxford life at the time, the drab, depressed nature of British politics at the time. I loved my college life, I loved my tutors. Again, as you know now from talking to me, I was at Harvard before, I was at Yale Law School afterwards, extraordinary institutions, but my educational experience – and it was terrific at both of those places, which I loved – but my educational experience at Oxford far surpassed my experience at either. I don’t think I could have had a better experience.

RW: Tell me more about that specifically. You read PPE. What drew you to that area of study?

EG: It was really the quality of the tutorial experience, and I was lucky. For whatever reason, Magdalen college, for those doing second BAs in PPE, treated us extraordinarily well, and I had the benefit of our own tutors, but also they ‘farmed us out’ for some of the papers in PPE to very distinguished tutors in other colleges. So, I had a tutor at Nuffield, a tutor at Queen’s and a tutor at St Hilda’s, in addition to the five tutors I had at Magdalen, and they were superb. And with two exceptions, all of them were one-on-one tutorials, and maybe the best of all was someone who would just not be, sadly, even today, at Oxford, but certainly not at in any other place at the time in the world, a don or a professor. I mean, he was a tutor, but he’d never got a PhD, he never wrote any books, I can’t remember if he ever even wrote any articles, but he was brilliant and he was a phenomenal teacher. And I had him teach me British institutions. I knew nothing about British politics, and he was phenomenal. I got to know him well and got to know his family, and then a series of tutors, some of whom I’m still in touch with. I had an email literally yesterday from – one of my papers was political sociology, whatever that is, and the tutor’s name, Bill Johnson (Richard Johnson (Natal & Magdalen 1964)). He was a South African Rhodes Scholar. He now lives there. He left Oxford and went back to South Africa. I could talk for hours about his career and the fascinating things that he’s been involved in. But he was fabulous.

Philip Williams was an extraordinary man at Nuffield College. He was the biographer of Hugh Gaitskell. And I, along with one of my Magdalen Rhodes Scholar PPE buddies, had tutorials with him, and he became an enormously influential person in my life. He visited me when I was in New Haven, and he did this with many of his other tutees, many people who became very distinguished in the United States, as journalists, as politicians in business. He just had an extraordinary-, I mean, he never married. You know, his rooms in Nuffield were a stereotypical mess. You know, it was like a tornado – papers, books, newspapers, everywhere, nothing ever cleaned. He probably had signs of at least 100 dinners, the stains on his tie every day. And he was magical. Partially because there was probably nowhere to sit in this messy set of rooms, we would typically walk around the Worcester College lake and talk about whatever it was that I had written an essay about. I had an extraordinary woman at St Hilda’s tutor me in one of my economics papers, and that was wonderful because it gave me a slice of women’s life at Oxford. Again, this was another world then. It was all men at most of the colleges. There were only a small number of colleges for women. So, there were far fewer opportunities for women and sports were all male, the clubs. One just didn’t see women very much, and it was horrible, although we didn’t know anything else, we didn’t know how horrible it was, but this was a great opportunity to see another part of Oxford. And then I had a person I did tutorials with, as I said, in Queen’s College.

I loved my life in the college, I had wonderful rooms, and I played sports. I was active in the Middle Common Room and it was very different from today. I revered, like most of my classmates, the Warden, Sir Edgar Williams, but we hardly ever saw him. I mean, we went into Rhodes House, we had our photo taken, we had a Coming Up Dinner, and we’d see him, maybe, once a year – I don’t think it was much more than that – where we’d walk into his office and he’d pour us a glass of sherry and he’d look down at some papers and mumble something about how our tutors thought we were all stupid and we would march on, and we revered him. But Rhodes House was not part of our life, as important as it was to us, and our lives were in our colleges. We had a wonderfully active Middle Common Room. I think it was the most internationally diverse, socially rich, academic experience I could ever have imagined. And to this day, Zimbabwean, Canadian, Australian, American friends. Very few British, which was actually a problem. There were very few British graduate students, and because my tutorials were one-on-one, the only British students I knew were the ones I rowed with. So, that’s a whole other set of stories and memories. And another thing, just thinking about it too, my friends then-, and again, I think we are so lucky that Rhodes House has become what it is for so many other students, but my best friends at Oxford – and I don’t know if too many Rhodes Scholars could say this today – yes, a few of them were Rhodes Scholars, and they remain my best friends today, but the vast majority of my closest friends were not Rhodes Scholars. They were fellow graduate students in my college, and I think of them very often.

I want to highlight just how important sports were to me. The amateur traditions, and the complete lack of big-time sports apparatus and culture that I think distorts American higher education so terribly, are so conducive to enjoying sport for its true and wonderful values. I took up rowing and loved it all six terms I was there, and still proudly have the oar I won on my wall. Jessica and I continued to row together until just a few years ago. I also played squash for my college, as I had in the United States, and learned to play cricket with my Middle Common Room team, as I surely had not...(though understood it having spent most of a high school year in India). Finally, and maybe most fun and with lifetime implications, I took up the wonderful and ancient sport of real tennis, (plain old "tennis" at Oxford, as distinguished from the upstart and many-centuries-younger "lawn tennis") on the court in Merton Street, and played matches all over England and not just against Cambridge for the University, but in three cities in France as well.

And another reflection on how different life was then: first, the absence of women, but it turns out that maybe my closest friend in my college – his name was Stephen Webster – was gay, but I had no idea he was gay. No one had any idea that they were gay at that time, and it’s one of the biggest changes, I think, between life then and life today. I think of him often because of the tragic life he led. First of all, hiding that from all of [50:00] us, including, ironically, a gay Rhodes Scholar a year ahead of me from Australia who also hid the fact that he was gay. And, that they didn’t discover that each other was until years later. Just unimaginable today. But I mean, you know, I visited his home. At the big commemoration balls, he would appear with a woman that he knew from his childhood and we all just assumed was his girlfriend and, of course, wasn’t. The tragedy there was – no one was coming out then, or could have, easily – that shortly afterwards, he won a scholarship to the United States and he was studying there. He went to Yale. And that was at a time when there were just the beginnings of liberation, but tragically, it was also the beginning of HIV and AIDS. He came out then, he abandoned all of us from his previous life. I mean, not that he had any reason to. He just moved into his exclusively gay life. Those of us were close to him were very hurt that he didn’t want to see us anymore, and then, you know, a year and a half later, he was dead. He died of AIDS, one of the first wave, and it was-, the fact that I never knew.

RW: Tragic.

EG: It was terrible. And he went to Saudi Arabia, I’d heard, for some imagined treatment, which of course didn’t work, and then he went home to Norfolk and died with his family. But there are people like Stephen whose lives were less tragic who were part of my life then and who remain a part of it today in a way that’s just disproportionately true compared to my educational experiences elsewhere.

So, that was my college experience and my academic and tutorial-related experience. But, you know, as I said, I played squash, and I rowed for my college. That was the only way I got to know my English friends. Of course, they were much younger, they were 17 and 18, but that was great fun. And, you know, another reason, I enjoyed my time as much as I did is by then, I had married Lucinda. That was funny too. Of course, then, you could not be married as a Rhodes Scholar in your first year. And indeed, to get married in your second year, you had to get permission from the Warden. So, I went in to get permission from Sir Edgar, and by then he already knew her and of course he gave me permission. She worked there the first year. She, of course, couldn’t live with me in Magdalen, and she worked for Blackwells scientific publications. But frankly, having her there exposed me to things that if I had been a typical Rhodes Scholar unmarried or unconnected in that way-, she exposed me to a whole other world, because her colleagues were British. Her best friend was married to a British graduate student I got to know well. So, much of our social life came through that side of things and we saw what living in Oxford was like, we lived in married accommodation our second year, and so we did our own cooking and shopping.

And then the other thing, because she had a full-time job, we didn’t travel as much as some of my classmates did. Also, it was harder to travel then, too. It was expensive. We didn’t have cheap flights so you could fly to, you know, Kyrgyzstan for the weekend, or whatever. And so, most of our time was spent in England, and even to this day – and when I was the American Secretary, among the many things when I had them captive before they would go off to England, I would tell them how sad it is for me when I meet Rhodes Scholars who come back from two or even more years in England and barely know England. You know, barely know London. They’ve never been to the Midlands, maybe not even to Scotland. And I thought one of the great experiences and opportunities we had then was the opportunity to really live in get to know another country, and it was facilitated for me by the fact that my wife worked, we didn’t have money to travel, travel was harder. So, our weekends, our vacations, were local, and we knew parts of the Cotswolds like the back of our hand. And I can still imagine driving – I’d borrow a friend’s car – to Minster Lovell and then to Blenheim and then to Lower and Upper Slaughter or going into London, which we did often. We discovered ballet during those days. Skiing, but not in fancy places in Switzerland or in Colorado, but in Scotland, of all places, in terrible conditions. But it was fun. So, that was another part of my life that I enjoyed very much.

RW: That’s so interesting. And how did you stay connected to home and family during those years?

EG: Oh, goodness. Well, that’s a very good question. It’s hard. You know, we stayed connected, but knowing what we know now-, I mean, first of all, even telephone was difficult. We didn’t have telephones. You know, there were these coin-operated phones in the Middle Common Room, and you’d hardly ever have the right shillings and there would be a line. You had to schedule all these things, and who knows if there would be people on the other line. But, it was letters, and occasionally you’d be lucky and your family would visit on a holiday if they could afford to. It was hard to keep up with our sports teams or American politics. Like much of the world, it was a critical time in American politics. There was a presidential election. But we had the International Herald Tribune and that’s where we would learn the next day. We’d go in the Middle Common Room and fight over that to see if the Red Sox won or what happened in a primary.

There was no other way, and even communicating with Oxford-, obviously, it was long before cell phones, and forget the internet. But the way we would arrange meetings with people was through the pigeon post. We’d write handwritten notes and drop them in our porters’ lodge, and they’d be delivered to someone at another college, and who knows when they would get those? So, there was nothing spontaneous, but it worked. You know, we didn’t know anything else, and it was, I think, fun. I think the pace of all of that-, again, I look back and wonder how we could have done it, but I loved it. And then I contrast that with the constant connectivity with just about everything, including horrific things, that my grandchildren have. It’s really another world. And again, that’s among the many reasons why I think that period was magical. One of the things about Oxford-, and I’ve been privileged with my roles with the Trust over the years, to get back far more than most, and with my business and my non-profit work for the last 20 years, I get to England a lot for that reason too. But there is something very special about Oxford that’s evocative of memory, because most of it just doesn’t change. You know, when I go into Magdalen or walk around Addison’s Walk or walk through the cloisters, I mean obviously that hasn’t changed since the fifteenth century, some of it. But even just the town of Oxford, you walk down Merton Street or New College Lane and it’s the same as it was when I was there and centuries ago. I mean, the only things that change are the quality of the shops and the food. They get constantly better and more expensive. It was all terrible when I was there. But otherwise, it’s the same. So, you’re brought back. You’re sucked back, into those memories, in a way that I don’t know anywhere else that does that [1:00:00], because infrastructure there, supports your thinking that you could be 50 years younger, and that’s pretty special.

RW: That’s really special, and beautifully said. And building on your impressions, can you reflect on some activities in the early 1970s while you were there that led to women being permitted to apply for the Rhodes Scholarship? Were you aware of what was happening at the time?

EG: Well, I was aware. But again, I’m sort of embarrassed that I was not engaged myself in this. I remember, I think he was president of the Harvard Crimson my junior year, I didn’t know what his academic record was, but you figure, here’s someone who clearly could be a Rhodes Scholar or be a strong applicant, and I remember him not applying, in protest, because women were not eligible. When I think about that I think, ‘Well, why didn’t I feel that way,’ or why didn’t more of us feel that way? So, I was aware there was the beginning of a movement. There were a few incredibly principled classmates whom I have now enormous respect for retroactively – at the time, again, embarrassingly, it didn’t register for me – who were protesting. While I was in Oxford I was a little bit aware, but again, we weren’t together as a cohort like Rhodes Scholars are today. We weren’t really kept up with Rhodes business like they are today. So, it wasn’t until I was back at law school in 1976 that I became much more directly aware of how, over the previous number of years, with leading efforts by Bill Barber, who was my predecessor as American Secretary – it was Bill, then David Alexander (Tennessee & Christ Church 1954) and then me – in that role, but a very substantial part of his tenure was working on these issues. And then, when I became his Assistant American Secretary in 1977-78, he told me a great deal about what that process had been like, and frankly, how close we came to the Scholarships being suspended for a while, because of the opposition of the US Justice Department and the complications of American law and British law.

But a lot was going on behind the scenes on the American side with my predecessor, with the Justice Department and at the Trust, and there was nothing easy about this. And there were also just supply problems, if you will. Remember what I said about how lucky I was to have a tutor at St Hilda’s. There wasn’t room for women at Oxford. There were just four or five traditional women’s colleges. When I was in residence at Oxford, though – with the wonderful name of ‘The Jesus Plan’ – there were four or five colleges that were traditionally men’s colleges that began admitting women. Jesus was one of them, hence ‘The Jesus Plan’. It was, I think, Jesus, Wadham, Brasenose. I’ve forgotten what the other was. I think there were at least four that began admitting some women while I was there. So, I saw that. But it wasn’t really until I got back that I realised all that was going on behind the scenes and how challenging that was, to finally open things up. As I remember, the first election that included women was 1976, I think, to enter in 1977. So, it was just after the time that I was there that it finally happened. And, of course, those early women, they could only go to the traditionally women’s colleges or those ‘Jesus Plan’ colleges, as people called them.

RW: Sure. Fascinating. You touched on this, and I just want to build for a moment on recollections from your time as a Rhodes Scholar of being in Rhodes House and interacting with the Warden. You have such a unique perspective because you have stayed in contact with all the wardens since, spanning four decades now.

EG: Actually, as American Secretary, I worked for seven wardens, and I knew three before that too.

RW: Exactly. So, share the perspective of your experience of Rhodes House and your interactions with the Warden as a Rhodes Scholar, and some of the most significant changes that you’ve observed.

EG: I think those changes are profound. But again, I can’t say that I got to know Sir Edgar Williams well. I mean, we always called him Sir Edgar. People then called him Bill Williams too. But we revered him, and he had this larger-than-life reputation, given his service in the war, his military service, his academic role. So, he was an intimidating figure, but also when necessary, a welcoming figure. I did have classmates or those in years just before me who had personal tragedy befall them. You know, the death of a father or a serious medical problem, and the Warden, and particularly the Warden’s wife, Gill Williams, was a wonderful, wonderful woman, and they opened Rhodes House for people in those circumstances. So, we knew we would always be welcomed if necessary. But it was just not part of our life. In fact, we were sort of signalled that it was not supposed to be part of our life. Our life was to be in our college and our course. And back then, the other major difference-most of us did BAs. So, in my class of 32, I think 24 of us did second BAs, whereas today, in recent classes, at most one or two would do a BA. And we could talk for hours about reasons for that, both the demand and supply side. It’s also, arguably, one of the hardest things to get admitted to, but there are many, many other things like the growth of one-year master’s degrees. You know, the University has changed in many ways.

But Rhodes House, we weren’t there very often, there were no activities there. It was long before there was a Rhodes Ball. There weren’t Thanksgiving parties. There weren’t meet & mingles. We wouldn’t have had a clue what that meant. But again, it was not in our world, so it wasn’t a concern. But as far as the biggest changes go, when I think about changes in the life of Rhodes Scholars, clearly the role of Rhodes House is the biggest change. I mean, there are changes in other ways I alluded to, like far more people doing master’s degrees, very few doing bachelor’s degrees. My sense is that especially for those doing one year master’s degrees, two one-year master’s degrees, I don’t think there is quite as much connection to a college, on average, as when one was doing the BA, but there are still strong connections. But as an example of how things are different, I don’t know when the Trust started surveying Rhodes Scholars in Residence about their experience at Oxford. It’s just a good thing to do, but certainly in our time we were not given any surveys. But I’m guessing that they were started maybe 20 years ago, 30 years ago, I don’t know. But in the early days of the survey – and I’m pretty sure this is right – there was not even a question about how important Rhodes House was to your experience. It wouldn’t have made any sense to ask the question. But to show you how much the change is, my recollection of seeing some of those surveys in the last eight or ten years, is that not only is it a question, but for many Scholars, it’s the most important part of their experience. So, that speaks volumes and Rhodes House is now openly, actively welcoming and engaging with Scholars in ways that we never thought of. But, you know, everything else is still in place at Oxford as well.

RW: That’s right. Thank you for that. What singular impact did the Rhodes Scholarship have on you personally, Elliot?

EG: For me personally, it is the fact that it allowed me to be in a position to have been the American Secretary for almost 25 years, which has been the greatest privilege of my life. I never applied for the job either. You know, today, thank goodness, it’s an open process, and like most things in the world, it’s all transparent. Not only did I not apply, but [1:10:00] in retrospect, I realise I was being interviewed for the job, but at the time I didn’t even know I was being interviewed for the job. I knew that there was a vacancy when David Alexander was no longer going to be the Secretary, and before I was American Secretary, I had been connected to selection one way or another for almost 50 years, because I served on the Virginia selection committee in 1978. But when David Alexander’s vacancy was evident and I was then a state secretary, I remember to this day writing a letter of recommendation, even though we weren’t solicited to do so. I wrote a letter suggesting a particular person and then I also remember explicitly in this letter saying that, ‘As you look at other people,’ – again sensitive to historical impressions and opportunities at different colleges and everything else – I said, ‘ideally the person should have had no affiliation with Harvard and not be from either the East Coast or the West Coast,’ and there were a few other things I suggested it should or shouldn’t be, all of which would have eliminated me. So, when a number of months later I got a letter from Tony Kenny, whom I barely knew, who had been the very distinguished Master of Balliol before he was Warden – and by the way, I’m still very close to Tony and Nancy. Tony is 94 or so. I mean, he wrote two books in his 90s and they live in Headington. Amazing, and I got an email from him the other day. But I got a letter in the mail from him, asking me to be American Secretary.

But I mentioned how I didn’t realise I was being interviewed. One day, I got a call at my house – I then lived about five miles across the Potomac here in Virginia, up the river – and I was sitting in my library, and I remember having a hard time understanding the person. And he was sort of mumbling in a very aristocratic English way, and I couldn’t even make out his name, but I figured it out afterwards, because it was Lord something-or-other. And enough got out was that he was in Washington and he wanted to meet with me. So, I said, ‘Sure,’ and we had lunch and by that time I’d figured out his name and I’d looked him up and he was the Chairman of the Trust. And the Trust then was a much smaller institution and entirely British. We had a very lovely lunch, and he explained that he was in Washington because his wife was an interior designer and there was an interior design conference, or something. And I had been involved in selection and someone may have given him my name and I honestly thought that he just wanted to have lunch with someone because he didn’t want to look at fabric at some design conference for the whole day. So, we had a lovely lunch, we were talking about various things and then, lo and behold, I realised subsequently that that was a job interview, but he never mentioned the job. So, I don’t know how I got onto that, but it’s a good story.

RW: It is a great story, and that’s the beginning, and you accepted this offer once you knew that’s what it was.

EG: How could I not do it? But honestly, the Rhodes Scholarship is an enormous privilege, and it changed my life in many ways. I mean, just the academic experience-, I mean, forgetting the Rhodes ‘title’. The Rhodes ‘label’ can sometimes be problematic, because it’s so prestigious, and in some settings, it could be off-putting to people, but the experience, especially being an undergraduate and the kind of experience I had, I don’t think a week goes by-, maybe I’m lucky because I work in a non-profit world where I still actually have a programme under me, Philosophy and Society. We do a lot of the same things, and politics and economics, so in a funny way-, but even before my last 20 years of professional work where it’s quasi-academic, in a way relating to politics, economics and even philosophy, I don’t think there would be many days where my academic experience in Oxford wasn’t relevant in a direct sense to things I was thinking about. You know, to this day, my interest in and understanding of European politics or how different governments work, or economics, or political theory as we think about the state of the world and the state of democracy. I mean, I wrote essays for tutorials – not that I can remember a word I wrote – but they’re still of relevance and they have been throughout my life.

Then, all the wonderful friends I have through Rhodes and Oxford. But I think the reason I got onto this other point is the fact that I’ve spent so much of my career helping the Trust in this very privileged volunteer way, you know, is just incalculably significant and valuable to my life, in so many ways. One, being that, as I’ve said on a number of occasions, the experience of dealing with young Rhodes Scholars is the greatest antidote there is to the cynicism or pessimism that sometimes can accompany ageing. You know, I also have now 10 grandchildren, so you can’t be pessimistic with so many grandchildren. But the world can be a very depressing, scary place, in my opinion, but being around the cohorts of young Rhodes Scholars who believe that they can change the world in usually very modest but significant ways, is the greatest thing I can imagine to feel good about the future. So, I wouldn’t have been able to have that experience and those exposures were it not for the fact that I had this opportunity myself.

RW: That is beautiful, and truly, the words that you speak are the epitome of lifelong fellowship and devotion and commitment, and I love your reference to it being an antidote, personally, to the prevalent depression and pessimism that is part of our worldviews today. You’ve been in this role and selection spanning four decades, and specifically as the American Secretary since 1993, is that right?

EG: Officially 1998, but I started in 1997, by shadowing David Alexander, if you will.

RW: Okay.

EG: And Joyce Knight, who accompanied me this whole time in this adventure, we went out to Pomona College where his office was, for the selections in November of 1997. So, we actually began moving the office starting in 1997.

RW: Tell me, during the that time, aside from the antidote of working with these incredible change-makers, what else kept you continuing to serve in this role? Are there significant highlights throughout the years that you think of when you reflect?

EG: Oh, look, I loved it. I mean, everything about it was great. The opportunity to connect obviously with the Scholars Elect, but even some of the outreach we did. And we’re lucky in the United States. The outreach challenge is much greater in the rest of the world. We’ve been here since the first elections in 1903, and most Americans, they might not be able to tell you exactly what a Rhodes Scholar is, or that it’s at Oxford, but the term ‘Rhodes Scholar’ has resonance more broadly in this country than anywhere else in the world – maybe Canada or Australia, it’s hard to compare – given the scale of them, and the history and the prominence of many of our people. But we still had reason to do outreach, to go to universities, colleges that may not have had [1:20:00] a historical connection. So, that part of the responsibility was fun, but it’s also been a privilege just to get to know so many Rhodes Scholars. Most of us don’t know many outside of our own class, but of course I had to put together selection committees, particularly when you consider the fact that the key to having a fair selection committee is a balanced selection committee, balanced in every conceivable way you can imagine. Although there is a limit: when you only have seven people, you can’t balance in every way, but you try very hard.

So, I’ve gotten to know so many Rhodes Scholars that way and that’s been a great privilege. The opportunity to get back to Oxford. We used to have a Secretaries’ week. It used to be every year, and then when the Trust started having some financial difficulties around 2008, it moved to every other year. But we’d literally spend a week in Oxford, and frankly, it was more social than work, and I think it was a way to, if you will, compensate us. And we all stayed in Rhodes House with our spouses and we’d have dinner together, we’d make breakfast together, we’d meet with faculty. So, when you say you do it so long, I mean, why wouldn’t you want to do it so long? And in another sense, one element of it is actually easier than being a selector, because my counterparts around the world who are national secretaries, almost all of them serve on a selection committee. But because we used to have eight districts and now we have 16 districts, I can’t sit on a committee. I mean, I’m sort in what we call ‘The war room’ as questions come up or as the decision are made. So, I’m not involved. I had the easiest job of any selector . I only read the dossiers of the 32 winners. That’s a pretty easy job, and I don’t have to make the hard decisions, and particularly the disappointing decisions. I was a district committee member for many years, in New England, and I was a state secretary. I don’t think there was ever a year where driving home after the district committee meeting, I didn’t have some mixed feelings. I mean, I always felt wonderful about the people we selected, but more often than not, I really felt bad that ‘Mary’ or ‘Tom’, who might have been in the fifth or sixth place but I thought was just wonderful – and we always had respectful dialogue – just, you know, I wish we could have sent six. I don’t think I ever felt that we shouldn’t have sent ‘Jim’ or ‘Mary’, but it’s hard work, you know.

And this is another thing, I think. Not all Rhodes Scholars are known for their humility, but I think it’s a critical factor to keep in mind. You know, if there any Rhodes Scholars that are not surprised or assume that of course they’re going to win a Scholarship, they probably shouldn’t win a Rhodes Scholarship. You know, the competition is intense, it is subjective, and ultimately, while we try to get consensus, it could be a four to three vote with respect to the person. So, those other people who are also finalists, you know, it’s hard to distinguish, and they’re all remarkable, and that’s difficult. And it could be different on a different day. You know, it’s not objective. It’s ultimately subjective, and it’s seven peoples’ subjective judgment. That’s why it’s worth spending a lot of time thinking about making the process as fair as possible, choosing the people as well as you can, and probably the most important criterion for a good selector is someone who is extremely conscientious and takes it seriously. It’s hard work, it’s difficult, because everyone they’re seeing is terrific. And I think it’s also helpful for all of us to understand how easily we could have been those in the room whose names were not read aloud at the end. And, you know, sometimes it could be just the luck of a different opening question, or not having been asked what you might have thought you might have been asked, or you might not feel well that day. Or, as I mentioned earlier, you might be in a physical environment where you’re not comfortable or you’re out of place, or is somehow alien to you. I mean, there are so many factors, and we do everything we can and, you know, the secretaries of these committees do an extraordinary job in creating an environment that’s as fair and comfortable and equitable as possible, but it’s hard work.

RW: It is hard work, and in a typical Rhodes Scholar fashion, you are so humble around how much work it takes from the leader’s perspective to ensure the process is fair and that the composition of the committees is as ideal as possible and that the environment is as dieal as possible. So, let me take a moment to thank you for being the leader on these very, very critical parts of our objectives. Can you take a moment to share with us your impressions about how selection has changed or not changed over the past decades that you’ve been working in selection?

EG: Well, I’d start by saying it hasn’t changed, honestly. Basic selection is remarkably similar to what it’s always been. The criteria have not changed. I mean, yes, the Trust a number of years ago recognised they needed to put Cecil Rhodes’s very nineteenth-century words more into a twenty-first century context, like the fondness for and success in ‘manly outdoor sports’. Its not like sports has been written out, but basically, the criteria are the same. It was the genius of the founder with respect to the criteria. You know, the foundational one is academic excellence, and after all, we’re not selecting leaders of the world. We’re choosing people who have the potential to be leaders to make a difference for others, especially a difference in the world in positive ways, but through the filter and experience of one of the world’s greatest universities.

So, fundamental is the academic ability, but it’s not enough, and that’s where you get indications of leadership, character, service, activity and so forth. So, basically, the selection process, looking for this well-rounded excellence, foundational intellectual academic ability suitable to Oxford, with an ambition that ideally is a very other-directed ambition, you know, to make a better world. And it can be in any context. It can be as a poet, as a teacher, as whatever it is. The criteria are the same, the process is the same. It’s letters of recommendation. It’s an essay, that again, originally, I think we all wrote in a couple of hours without much worry. Now it’s a whole other process, which has been a challenge for us in selection. Once we knew that in some cases people would do 20 or 22 drafts, assisted by faculty. So, that’s one change I made, among many little tweaks, requiring an attestation that the work is exclusively that of the students. But the essay, multiple letters of recommendation. No other scholarship in the world or fellowship I know of requires five letters or as many as eight, and there is good reason for it, because we’re looking for all these dimensions and we take it very seriously. We take very seriously an understanding of the person, which is why the interview is so important as well. So, nothing has changed.

You know, to bring up what I think is a very minority view, just recently, because of the extraordinary diversity of many classes over the last number of years, there is a very small number of very well meaning, [1:30:00] engaged Alumni who think that obviously diversity is now a factor for selection. Absolutely false. I mean, and transparently absolutely false. You can look at the selection guide and it explicitly says – which is my guidance and the Warden’s guidance – that balance of any kind is not appropriate whatsoever. I think what is confusing to that small number of people who have that criticism is that they don’t understand the role Rhodes House now plays in the lives of Scholars in Residence, and Rhodes House is playing explicitly a more engaged and inclusive role in the lives of Scholars in Residence, and appropriately recognising that, a student who wins a Rhodes Scholarship who comes from a not very well resourced university in West Africa or East Africa or wherever it may be may need some help in getting acclimatised – also the climate too, with the terrible climate in England – to the academic environment in England.

Also, as we’re expanding in new jurisdictions, we need to do outreach and we need to do outreach particularly to groups and individuals who might not otherwise think that this is something they can aspire to. In some parts of the world, the assumption is unless someone goes to university X or unless someone is this-, so, the Rhodes Trust talks about those things, as they not only need to talk about them, but do things. But when it gets to the actual selection process, it is the same as it’s always been. And also, people need to remember, these are the decisions made by committees, primarily Rhodes Scholars themselves, who are making these judgements, and those judgments are based on the same criteria without any balancing considerations whatsoever. And in the United States, just as an example, we have 16 committees, and the people who’ve been with me on those selection nights know, we have no idea- I can’t think of another academic institution that operates like this. You know, most universities ‘build a class’. You know, they want a first baseman, they want a viola player, they want chemists as well as linguists. We don’t do that at all, and literally, we could have a class elected – and thank goodness it never happened on my watch, but it could. It would be a public relations issue to explain – but we could elect a class this November that is 32 men, you know, all from schools like Stanford University, all on the same sports teams and all whose parents live in places like Atherton or Pacific Heights but in different states. It’s entirely possible. And when a selection committee is meeting together and they’re choosing two people, there’s not even any suggestion that it’s a problem if they choose two people who are the same gender, the same major, the same university, from the same town. The diverse class that emerges is the product of an entirely, I think, scrupulously fair, decentralised process, managed by the individual decisions and judgments of Rhodes Scholars who are responsible for choosing strictly on merit and on the criteria that have guided the Trust since 1903.