Born in Port Pirie, South Australia, Elle Leane studied at the University of Adelaide before going to Oxford to read for a DPhil in English. Returning to Australia, she took up an academic post at the University of Tasmania and began to work on cultural aspects of human engagement with Antarctica, publishing Antarctica in Literature in 2018. Leane was also the Associate Dean Research in the University of Tasmania’s College of Arts, Law and Education, from 2020-2022. Alongside her academic work, she has continued to support the Rhodes Trust, serving on selection committees, as Tasmanian Secretary and as one of Australia’s deputy national secretaries. This narrative is excerpted from an interview with the Rhodes Trust on 2 September 2024.

Elle Leane

South Australia & Magdalen 1995

‘Science seemed like a more practical choice’

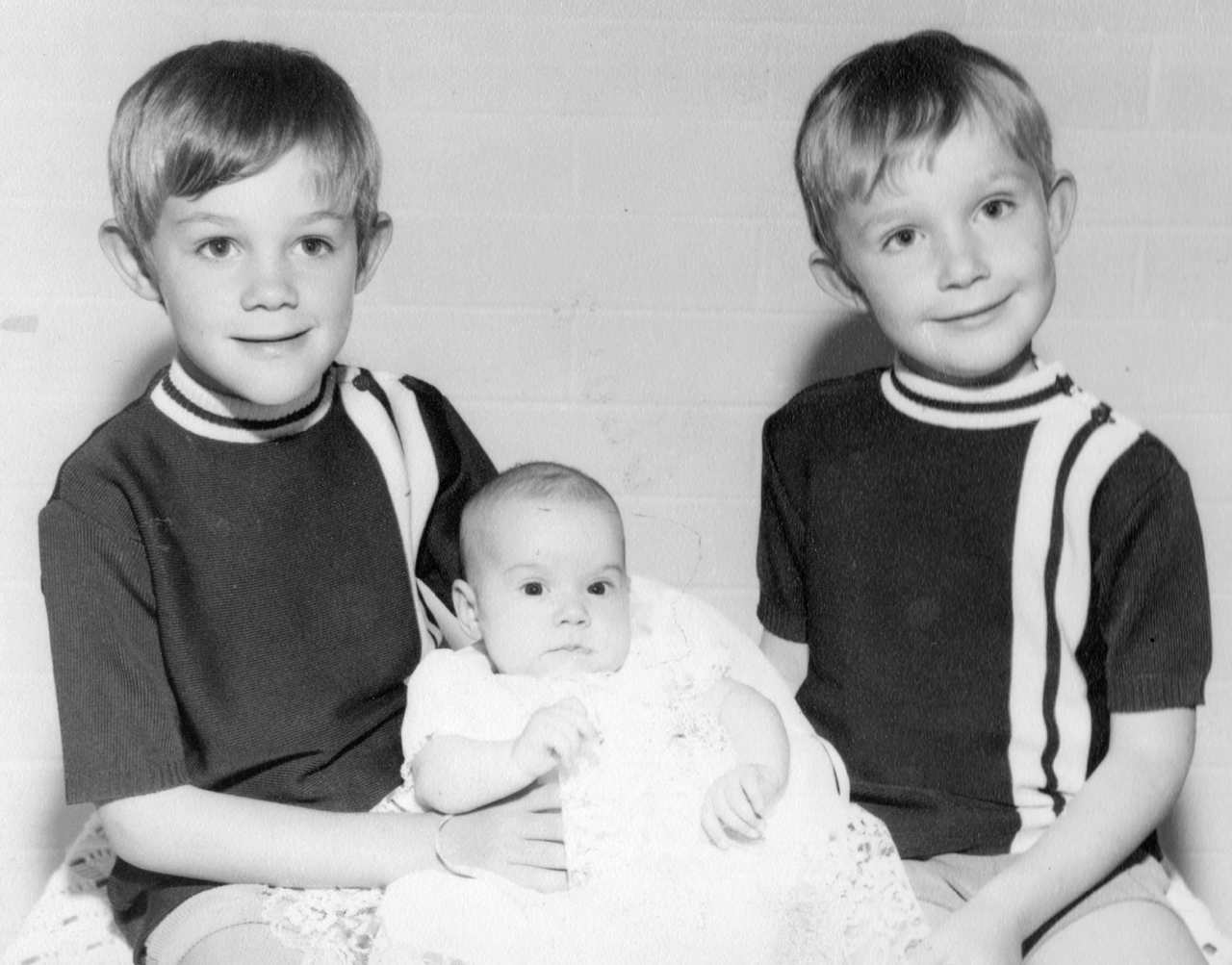

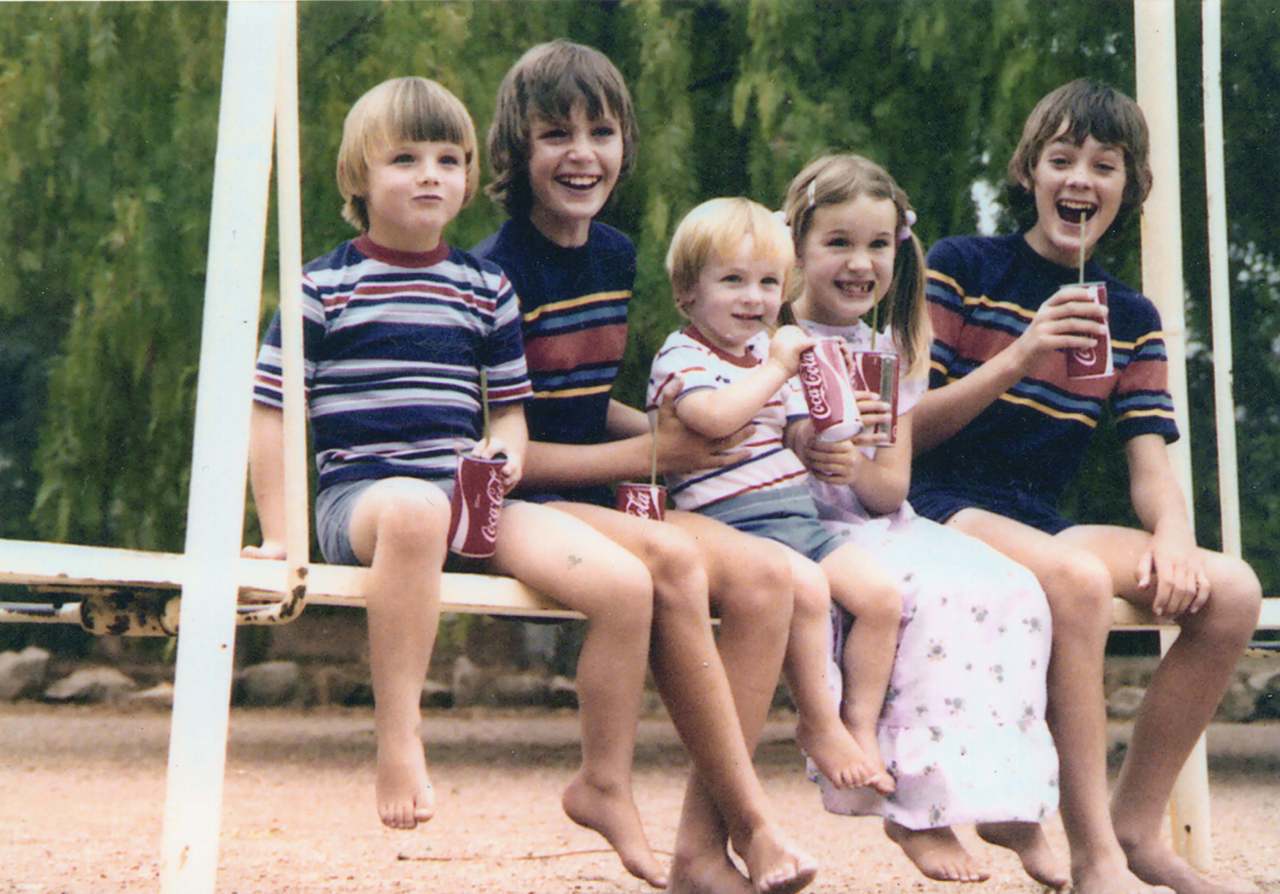

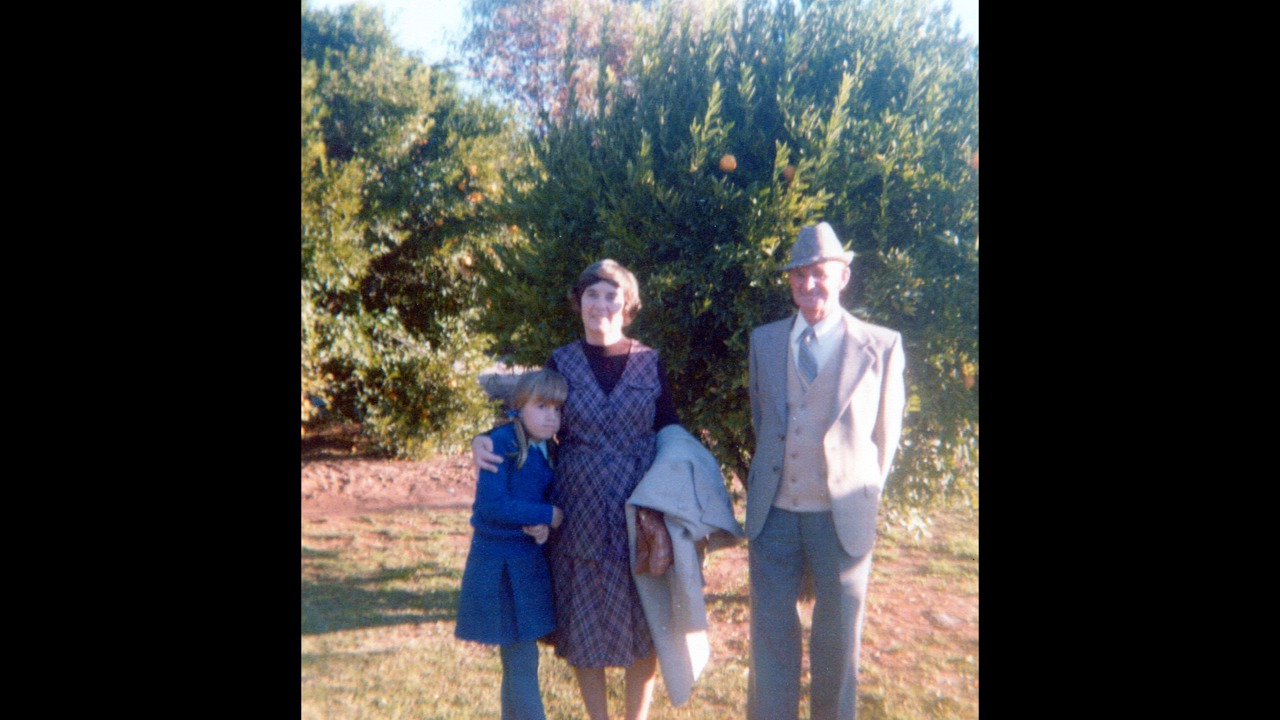

For the first 12 years of my life, my family lived in Port Pirie, which was a lovely place to grow up. I could ride my bike pretty much anywhere in town, both my sets of grandparents lived nearby, and it was a close community. I played sport, but what I really enjoyed was theatre. I think that’s been a very useful skill, actually, in my life, because as an academic, you have to do a lot of public speaking.

After we left Port Pirie, we went to Melbourne with my father’s job, and then on to Newcastle, on the east coast of Australia. I didn’t really like the first two high schools I went to, although I made a lot of good friends, but my school for my final two years was much better. It was a large, liberal-minded Catholic school and I had lots of options. I was equally attracted to sciences and to the humanities and social sciences side, but I decided to choose science at university because it seemed like a more practical choice. I’d also won a scholarship for women in science and engineering which would pay all my fees. So, I moved back to South Australia, where I’d grown up, and went to the University of Adelaide.

I had a lot of fun at college, probably a bit too much fun in my first year, and then I had to work quite hard. Halfway through my physics degree, I remember talking to my parents and saying, ‘I don’t really think this is for me. I think I might switch.’ They said, ‘Well, you can switch, but finish the degree first,’ which I’m very glad I did. I actually got the Bragg silver medal for best student in the undergraduate degree. Then, somewhat to my parent’s consternation, I called their bluff and enrolled in an arts degree, and I loved pretty much every minute of it. There were difficult times as well: when I get stressed, I suffer from anxiety, but I was lucky enough that it wasn’t debilitating. I loved learning and all I wanted to do at that point was continue in the university sector as long as possible.

On applying for the Rhodes Scholarship

I don’t know where I first heard about the Rhodes Scholarship. It was one of those things that was just in my consciousness. But I applied for pretty much every scholarship I was eligible for, and some that I probably wasn’t. My ambition was to go overseas, and I wanted to study rather than just backpacking around. I thought, ‘That’s how I’ll see the world.’ And then, my honours supervisor shoulder-tapped me and said, ‘You should apply for the Rhodes,’ because he thought my combination of doing well in physics and then doing very well in literary studies was highly unusual, and something I should capitalise on. He really gave me the confidence that I could do it.

At first, I’d actually wanted to go to Cambridge, which felt like the more science university, and I was interested in bringing my scientific work and my arts work together. But when I won the Rhodes, I wasn’t going to say ‘No’ to that! In my application and my interviews, I was very clear that my leadership was going to be in the academic domain. I said, ‘I want to do some innovative things, but as an academic.’

‘Like moving from the periphery to the centre’

My time at Oxford was very, very rich for me, socially and intellectually. To start with, I’d never been overseas before, and I remember arriving incredibly early in the morning after my flight, getting out on the High Street outside Magdalen, and it was the most beautiful morning, with the sun shining on the tower. And then, I dragged my suitcase past the deer park. The deer park! It was all quite surreal, and I was so jetlagged that I didn’t even remember most of the events I went to and the people I met those first few days.

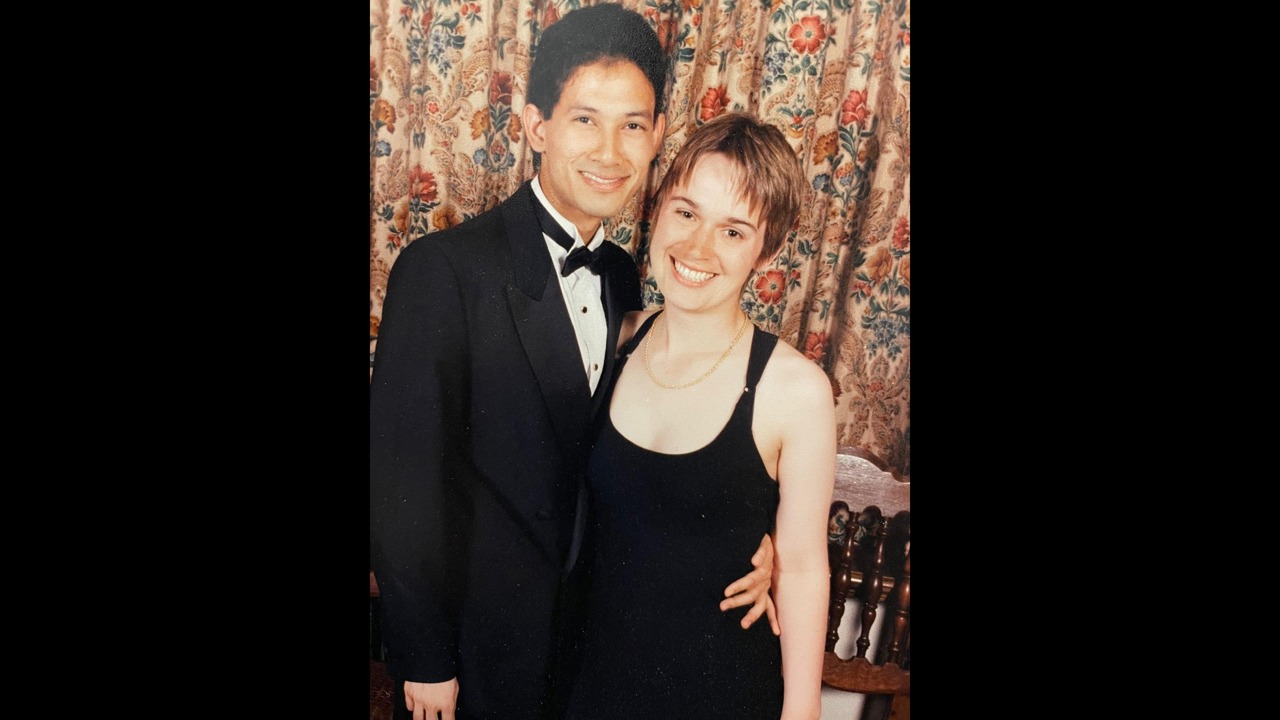

I had three social circles – in the English faculty, in Magdalen, and then with my fellow Rhodes Scholars. I joined the Rhodes ball committee, which was a great way to meet people, and I’m still friends today with some of the people I met through that. Having grown up in Port Pirie and ending up in Oxford did feel like moving from the periphery to the centre, and it was quite amazing to be able to go along pretty much every week and listen to people who were essentially famous, whether as writers or in other areas. That was incredible.

The actual degree was a bit of a lonely experience. Doing a DPhil in literature at that time, it was basically just me and the library. I’d come to Oxford to study 20th-century science fiction and then, only about a week in, I had an epiphany in Blackwell’s, the big bookshop in Oxford. There was a table of popular science books – this was the 1990s, and Stephen Hawking’s A Brief History of Time had launched a kind of popular science craze – and I realised this was the genre I wanted to study. I went to my supervisor and said, ‘I’m switching topic,’ and I shifted from literary studies into publishing studies. I began to interview booksellers and go along to science festivals and be in the pressroom. I’m an introvert, so that was all a bit scary for me, but also so interesting. I do wish I’d had more confidence in myself at that time, to switch to a different supervisor who was closer to my new specialisation, but it was still a really good experience.

‘I had Antarctica coming at me’

When I arrived to take up my role at the University of Tasmania, I realised I was at a university that didn’t have particular expertisein the field of science popularisation that I’d been working in. Hobart, where I lived then and still live, is a kind of Antarctic city, with an icebreaker going in and out and a lot of Antarctic scientists, which meant I had Antarctica coming at me. I began to think about Antarctica from a literary point of view, and when I managed to get a trip there as a writer-in-residence on a scientific programme, that really whetted my appetite.

After I’d published my book, the sensible thing to do would have been to move on to the next literary project, but by that time, Antarctica had gripped me. So, now, I look more broadly at how non-specialists connect with Antarctica, whether through literature or tourism, or in other ways.

These days, too, my interest in science communication is becoming more and more important, with climate change being what it is and given that Antarctica is eventually going to be the source of more sea-level rise than anywhere else in the world. Being able to communicate that and thinking about how people form their understandings of the continent and what’s going on there takes me right back to my first degree in some ways. I’m pretty sure I would never have gone in this direction if I hadn’t studied physics.

I see myself as something of a generalist, interested in human cultural engagement with Antarctica. That means I get to work with scientists a lot, and I love bringing together that more empirically, analytically minded part of me with the literary, storytelling part. That is what Antarctica has given me.

‘You don’t need to do things that stretch you out of shape’

Life always has lots of challenges, and for me, I had a particularly tough time dealing with breast cancer during the pandemic. The treatment was difficult, but it was actually going back to work afterwards which I found hardest. I had a pretty full-on position in the university, and I wasn’t really 100% well, either physically or psychologically. I was lucky: I had a good prognosis. But it gave me more empathy for others struggling with challenges.

That experience also reinforced something I’ve learned over the years, which is to hold true to the ways I think I can make a contribution and not get distracted by opportunities that seem superficially attractive. I think, especially if you’re a Rhodes Scholar, it’s easy to look at your contemporaries, who may be in big, public roles, and feel that’s what you should be doing too. The good news is that getting older and getting a better sense of yourself helps increase your confidence. It means you can still do things that stretch you, but you don’t need to do things that stretch you out of shape.