Born in Pretoria in 1953, Edwin Cameron was first appointed to the bench by President Mandela in 1994, who called him ‘One of South Africa’s new heroes’. Cameron went on to serve as a Justice at the Constitutional Court of South Africa. An activist across the field of human rights, he is particularly known for his anti-apartheid stance and for his work on HIV/AIDS and on LGBTIQ rights. This narrative is excerpted from an interview with the Rhodes Trust on Wednesday 23 August 2023.

Edwin Cameron

South Africa-at-Large & Keble 1976

'The big break for me was education'

I grew up in a disrupted home. My father had catastrophic drinking spells which had a very severe impact on the family. And also, unusually for that time, my mother was Afrikaans, so I grew up bilingual and Afrikaans is actually my first language. My parents divorced a second time just as I entered school, and then I spent almost five years in a children’s home with two sisters, one of whom, at the end of our first year in the children’s home, was killed in a traffic accident. I mention it because it marked my childhood significantly.

The big break for me was education, both at Pretoria Boys High – an elite state school, publicly funded – and then at Stellenbosch University. And then, the Rhodes Scholarship, which opened the world to me. Many of my teachers were brilliantly gifted, energetic and imaginative. I have such respect for those who become teachers. I don’t think there is anything more beautiful or important that you can do with your life than to pass on insights, knowledge, wisdom and protection.

The important point about all these opportunities that took a kid from quite a poverty-stricken background through excellent secondary education, excellent tertiary education, was that they were all white. Pretoria Boys High: whites only. Stellenbosch: whites only. At the time I got the Rhodes Scholarship, no black person had ever been elected to it in almost 75 years, even though Rhodes said in his will that, ‘No student shall be qualified or disqualified for election to a Scholarship on account of his race or religious opinions’. I was intensely conscious of race and how my way out of poverty had been defined by the privileged position granted to me because of my race, and that left me with an intense sense of responsibility. I wouldn’t say guilt, because I think guilt is a negative emotion, but a sense of opportunity and positive responsibility.

So, my background made me conscious of poverty and disadvantage, but also of the importance of public investment. I think it’s absolutely vital that there should be a strong governmental sector intervening in the displacement of privilege, the allocation of opportunities.

On applying for the Rhodes Scholarship

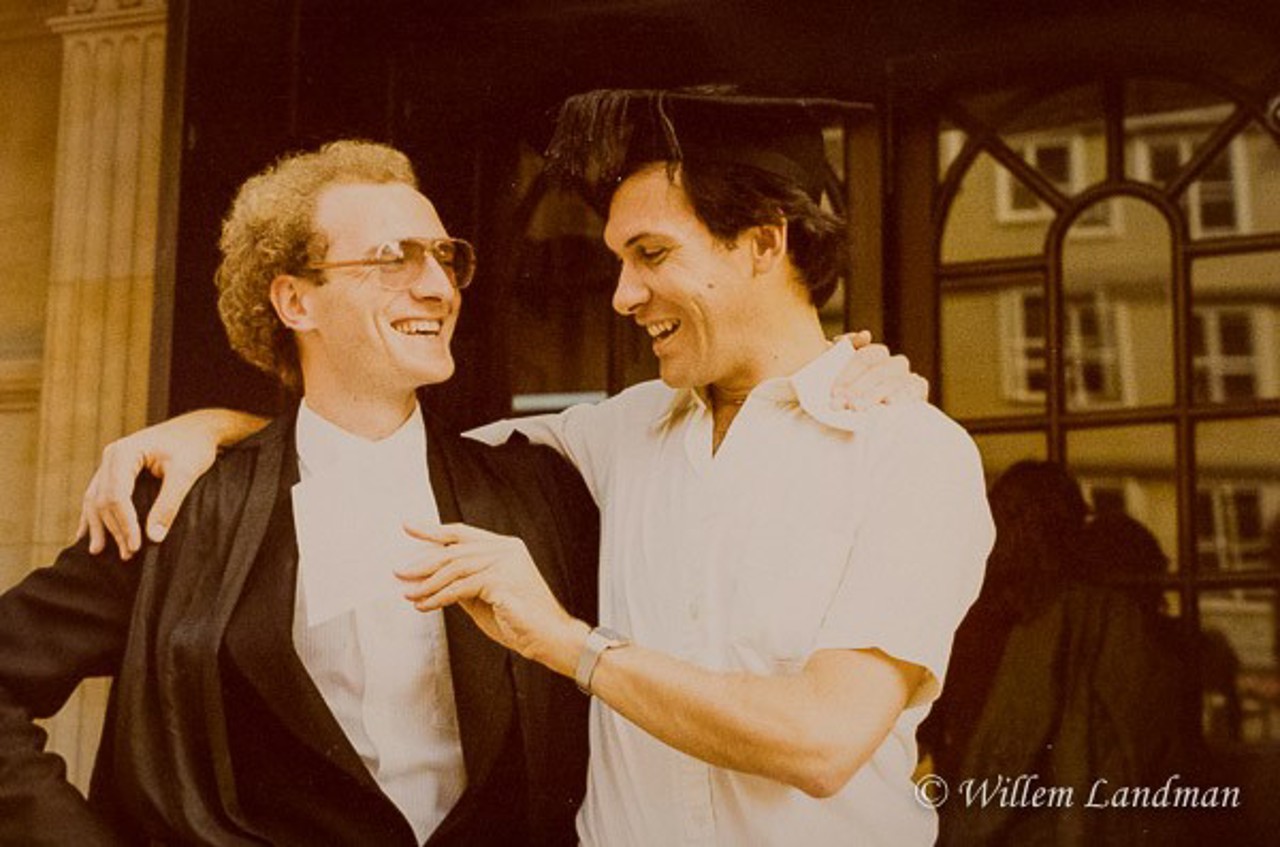

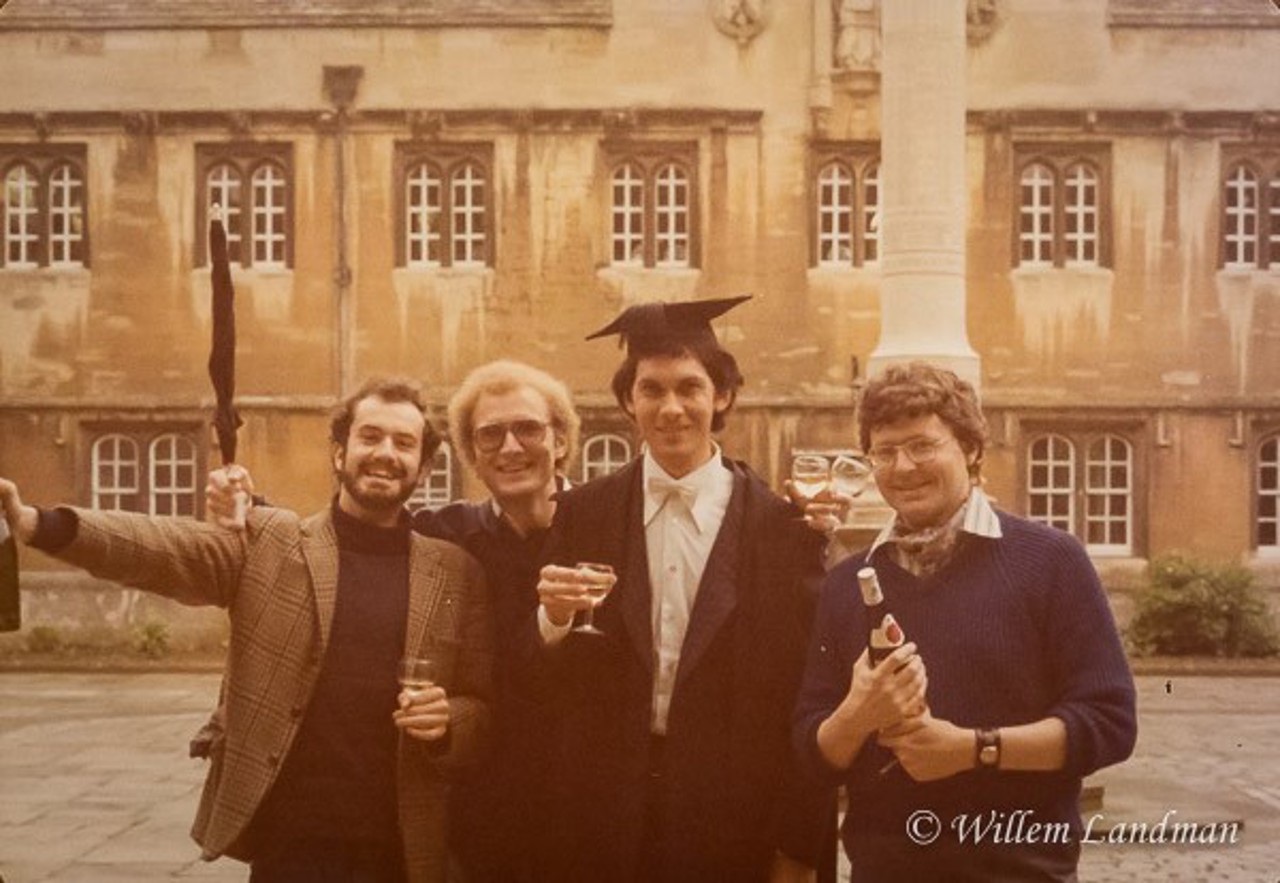

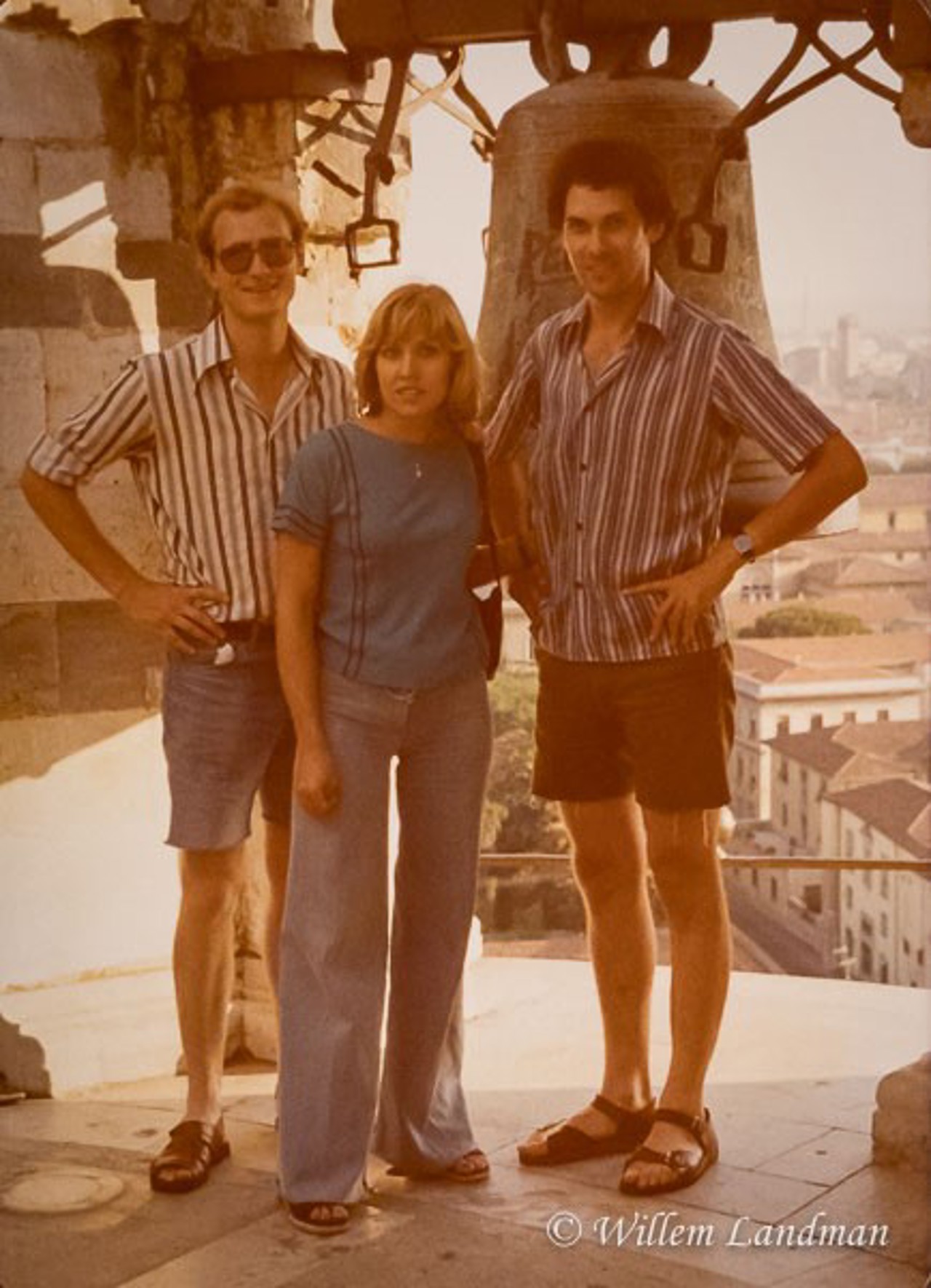

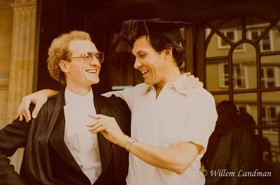

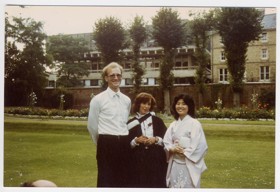

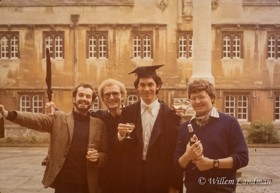

One of my schoolmasters at Pretoria Boys High had three brothers, all of whom had got the Rhodes Scholarship, so that made a big impression. And then, at Stellenbosch, there were two men who had been elected to the Scholarship two years before me. One of them, Willem Landman (South Africa-at-Large & Corpus Christi 1973) became a dear friend. The Scholarship had mystique and prestige and what it seemed to offer held a deep allure for me. And I have to say that I was also very ambitious, so it appealed to me on that basis.

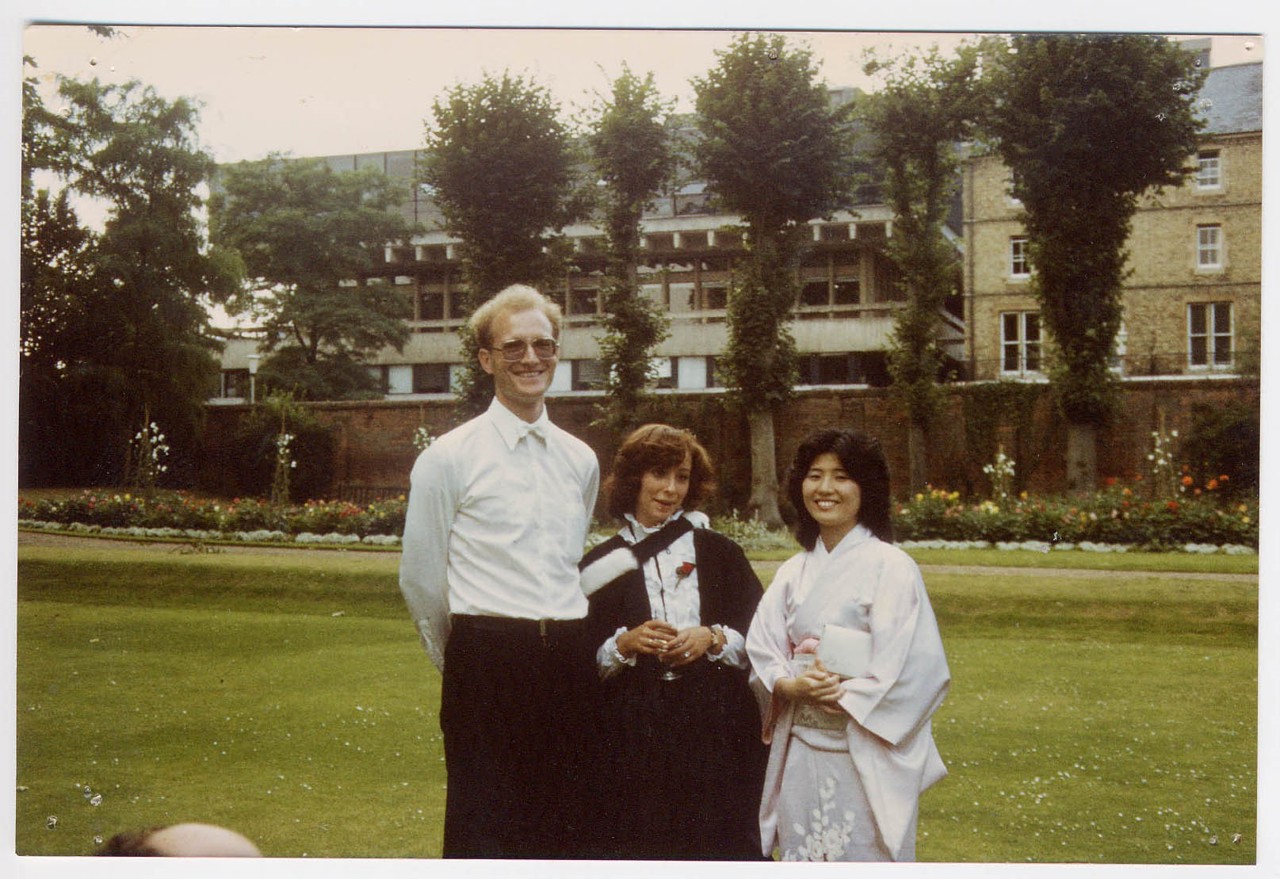

At Oxford, I was a swot. I was preoccupied with my reading and tutorials and essays and exams. But I also made profound friendships. Meeting Loyiso Nongxa (South Africa-at-Large & Balliol 1978), for example, was such a joy, and he was my first intimate black friend. That’s one of the things that Oxford did for me. Before that, I had never been met a black South African except in a situation where there was a hierarchically differentiated relationship. Amazing.

I started off reading classics, but changed to law at the end of my first term. My law tutor, Jim Harris, made a huge mark on me in my legal mode of thought. He agreed to let me do the Jurisprudence BA in five terms, rather than the seven which the British undergraduates did and the six that the graduate arrivals did, the second degree. He was blind, and I think the relevance of his sight disablement is that it made him rigorous and systematic, and he taught us in that way. Everything had to be ordered, because he had to hold it in his head.

So, there were parts of my experience at Oxford that were wonderful, but also some elements that I found very difficult. I’m ashamed to say that I was a snob, and I was horrified to find myself in a red brick, nineteenth-century college that didn’t fit my idea of beautiful Oxford at all. Well, I was wrong to think that, because Keble was very good to me. It taught me to look for substance and engagement.

'Never again would I apologise for something intrinsic to myself'

My queerness is one of the things that has shaped my life. At the age of 14, I became aware of my same-sex orientation. I felt a terrible sense of shame about it, wanting to keep it secret and, indeed, keeping it secret until the breakdown of my opposite sex marriage. I had two spells at Oxford, the first for two years, the second for one year, and it was after that second spell that I decided, ‘Never again’. Never, ever, ever again would I apologise for something so intrinsic to myself, something constitutive of my humanhood.

But Oxford was, at that time, very homophobic, and it was like that, I think, because of the preponderance of public schoolboys and that attitude that belonged to the English ruling elite at that time. In that world, buggery was alright if you kept it quiet and somehow got away with it. Being gay was not a constitutive element of your life or your being or your humanhood. That is despicable and hypocritical.

I remember going back to a formal dinner at Oxford. Late in the evening, my tutor made a comment about the Cambridge spies and their conduct. They betrayed their country in favour of a totalitarian system. And then he added, ‘And, they were buggers’, or something like that. I felt ashamed at not challenging him there and then. But I’ve thought about it recently, and I think not doing so was understandable. It was Jim’s occasion, he was the guest of honour. But I could have written to him afterwards and said, ‘You know, Jim, I’m gay. I’ve come out as gay.’ I didn’t do that either. And then, very sadly, he died, in his early 60s.

And of course, on the positive side, the great change that happened during my time at Oxford was the opening up of many of the men’s colleges to women. In my first two years, Keble was men-only. When I came back, there were women too, and it was immensely, immeasurably improved.

'The Rhodes Scholarship can be a buffer'

After I left Oxford, I started to practise as a lawyer, using the instrumental properties of the law to try to secure social and individual justice. I was in practice for about 11 years, and then I became a judge. And during this period, my life was also shaped by my seroconversion with HIV. After my diagnosis, I kept it a secret for 11 years. So, the stigma of HIV was also a very powerful influence in my life. There was the shock, then, of having a severely foreshortened expectation of life and, almost worse, the shock of feeling the intense shame that was associated with HIV. I’m giving a lecture next week at a medical school on AIDS, and the central issue, still, is stigma, because people still don’t want to talk about it because of shame.

My legal work was very full. It was mostly human rights, but not exclusively. There was some commercial work, some AIDS work. There was some LGBTIQ equality work. And I must say too that in all of this, I found that the Rhodes Scholarship was like a buffer, a shield. It does give you a certain cachet. I don’t say this with smugness or pride. But I think it helped protect me, because I was openly queer and also a very outspoken critic of apartheid and apartheid judges, and I could have been targeted more. Some of my legal colleagues were subjected to detention, and I don’t think it’s fanciful to say that the fact that I had excelled academically at Oxford and had been a Rhodes Scholar helped me in some ways.

'Privilege does bring responsibility'

As someone who has been lucky enough to be involved in selection of Scholars over the years, I have spoken at the Bon Voyage events for Scholars from South Africa. What advice do I give? ‘Be easy on yourself. Be gentle. Abate those anxieties. You’ll have more power to achieve what you want to achieve if you worry less. Let life happen.’ I don’t mean by that that we shouldn’t work hard or have a focus, but the process of doing so is good in itself. Try to enjoy it.

The other thing I would say is a truism, but it’s also a truth: privilege does bring responsibility. I think we live in a terribly unjust world, a world where horrible things are happening – but in which there is nothing wrong that can’t be remedied by human intervention. There is so much that you can do joyfully and constructively to change the world, and the Rhodes Scholarship empowers you to do that.